Since 2006, the National Book Foundation has been celebrating the work of extraordinary young fiction writers from around the world with the 5 Under 35 prize, given each year to “young, debut fiction writers whose work promises to leave a lasting impression on the literary landscape.” In addition to being recognized at a special reading during National Book Awards week each November, honorees also receive a cool $1,000 to spend on, well, whatever literary prodigies spend their money on.

Previous winners include luminaries like ZZ Packer, Karen Russell, Téa Obreht, Valeria Luiselli, Justin Torres, Angela Flournoy, Phil Klay, and many more of the most exciting voices in contemporary fiction.

The fourteenth round of honorees was just announced today, so let’s take a look back at all the literary wunderkinder of years past.

2018

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Friday Black

“In Friday Black, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah has written a powerful and important and strange and beautiful collection of stories meant to be read right now … Friday Black is an unbelievable debut, one that announces a new and necessary American voice. This is a dystopian story collection as full of violence as it is of heart. To achieve such an honest pairing of gore with tenderness is no small feat … In Friday Black, the dystopian future Adjei-Brenyah depicts — like all great dystopian fiction — is bleakly futuristic only on its surface. At its center, each story—sharp as a knife—points to right now.”

–Tommy Orange, The New York Times Book Review

Deep Dive: Read an excerpt from Friday Black

Hannah Lillith Assadi, Sonora

“Assadi writes poetically about the Southwest … the spacious, moneyed homes, the high school football stadium that looms over her hometown … But the fast-developing landscape is also thick with an air of threatening mystery … when she returns to the desert, her story about a heartbreaking friendship once again becomes sorrowful and singular, a mesmerizing take on tripping blindly into adulthood.”

–Maddie Crum, The Huffington Post

Deep Dive: Hannah Lillith Assadi on growing up in a phantom-filled desert

Akwaeke Emezi, Freshwater

“The novel is based in many of the realities of the writer’s life, but the prose is infused with imaginative lyricism and tone. In the end, this coming-of-age novel also has one foot on the other side, held between the open gates—a young woman of many nations and many souls. The journey undertaken in the novel is swirling and vivid, vicious and painful, and rendered by Emezi in shards as sharp and glittering as those with which Ada cuts her forearms and thighs, in blood offering to Asughara … Emezi’s lyrical writing, her alliterative and symmetrical prose, explores the deep questions of otherness, of a single heart and soul hovering between, the gates open, fighting for peace.”

–Susan Straight, The Los Angeles Times

Deep Dive: Read an excerpt from Freshwater

Lydia Kiesling, The Golden State

“The Golden State anchors Daphne’s journey in the visceral and material realities of motherhood. She’s on her own with Honey, rendered so realistically by Kiesling that her ‘puppy smell’ almost wafts off the page … Kiesling repudiates the classic American literary idea of the West as untrammelled wilderness or open space available for the taking, and Daphne’s relative ease of movement in the present is set against her husband’s restricted mobility across international lines. The novel beautifully depicts the golden light of California, the smell of the fescue grasses, the thinness of the air, and the way that Daphne and Honey often feel overwhelmed by the scale of the spaces they find themselves in … The novel is not treacly about motherhood, love, or domesticity. Daphne often finds herself at the edge of some very wild territories, as when wrangling the tantruming Honey … Many novels have decided that it would be easier to just turn away from this kind of wildness, instead of running full tilt toward it.”

–Sarah Blackwood, The New Yorker

Deep Dive: Read an excerpt from The Golden State

Moriel Rothman-Zecher, Sadness Is a White Bird

“Searing in its beauty, devastating in its emotional power, and dazzling in its insights, Moriel Rothman-Zecher’s debut novel, Sadness Is a White Bird, is, I promise you, like nothing you’ve ever read … His particular vision of today’s Israel, told through a coming-of-age story, will break your heart … The novel sings out in the distinctive voices of Rothman-Zecher’s characters, in their almost palpable presence, and in their hopes and hesitations … Rothman-Zecher shows great skill in portraying different neighborhoods, not only in terms of physical characteristics, but also through capturing the cultural and atmospheric dimensions … I have only praise for this poetic, distressingly original book.”

–Philip K. Jason, Washington Independent Review of Books

(Deep Dive: Advice from this year’s 5 Under 35 honorees on writing a second novel over on Lit Hub.)

2017

Lesley Nneka Arimah, What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky: Stories

“A witty, oblique and mischievous storyteller, Arimah can compress a family history into a few pages and invent utopian parables, magical tales and nightmare scenarios while moving deftly between comic distancing and insightful psychological realism … As in most collections, a few entries are less successful, but throughout Arimah demonstrates a deft wit and an ability to surprise herself—and her readers—with the depth and delicacy of her feelings … Arimah’s magic realism owes something to Ben Okri’s use of spirit beliefs, while her science fiction parables, with their ecological and feminist concerns, recall those of Margaret Atwood. But it would be wrong not to hail Arimah’s exhilarating originality: She is conducting adventures in narrative on her own terms, keeping her streak of light, that bright ember, burning fiercely, undimmed.”

–Marina Warner, The New York Times Book Review

Deep Dive: Read Lesley Nneka Arimah’s short story “Skinned,” which won the 2019 Caine Prize

Halle Butler, Jillian

“These two main characters are incredibly unpleasant, but not unsympathetic, and the point of view that Butler chooses is brilliant … To Butler’s great credit, the real villain of the book turns out to be neither Megan nor Jillian, nor any one person in their lives, but rather, the institutionalized inequalities and traps, including patriarchy, that many of us are intuitively resentful of, but that we cannot fully grasp, so instead we take our anger out on ourselves and one another … This is a grotesque and absurd book about grotesque and absurd people stuck in a system that is itself grotesque and absurd. It may be the feel-bad book of the year.”

–Kathleen Rooney, The Chicago Tribune

Deep Dive: Halle Butler on the frustrations of living

Zinzi Clemmons, What We Lose

“The themes explored in What We Lose—race, identity, family, and loss—are familiar, but their presentation here feels entirely fresh and new … made up of poetic vignettes that combine to create an unforgettable portrait of a young woman’s search for identity … beautiful poignant prose makes What We Lose the kind of novel you might find yourself marking up as you underline a sentence on every other page. Clemmons’s prose is sharp, and though the book is slim, it’s a rich novel with more depth and innovation than many novels double its length.”

–Rachel León, The Chicago Review of Books

Deep Dive: Zinzi Clemmons on the importance of editors of color

Leopoldine Core, When Watched: Stories

“Once a reader has taken the deep dive into 19 separate stories encompassing 19 distinct characters, this line serves as a kind of a roadmap to the whole collection. What matters to these stories, almost exclusively, is the inner lives of the characters who people them…Core’s characters are not tremendously different from one another: most are in the midst of a relationship, conversing with a sexual partner during their few brief moments on the page, and many self-define as writers or as artists …a minimalist in her use of detail, but her plots are well developed, even if they play second fiddle to the subjective experience of the events that unfold … With so many stories, When Watched repositions the reader constantly, so that the characters’ ever-shifting worlds, and the ways in which they make sense out of the chaos they create, become a means through which the reader creates logic as well.”

–Brandon Williams, Los Angeles Review of Books

Deep Dive: Read an excerpt from When Watched

Weike Wang, Chemistry

“…one of the year’s most winningly original debuts … Nearly every page is marked by some kind of breezy scientific anecdote or aside—pithy, casually brilliant ruminations on everything from meiosis and mitochondria to what makes rockets fly. That it’s all so accessible and organic to the story is one of the book’s most consistent pleasures. So is the texture and tone of Wang’s language, a voice so fresh and intimate and mordantly funny that she feels less like fiction than a friend you’ve known forever—even if she hasn’t met you yet.”

–Leah Greenblatt, Entertainment Weekly

2016

Brit Bennett, The Mothers

“…[a] fantastic debut novel … The genius of The Mothers is how Bennett uses those feelings in service to a story that could take place in any part of American society … Bennett takes the common experience of unwanted pregnancy and makes it newly significant through the lens of a tight-knit community still blinking from its emergence into safety and prosperity … Bennett has written that rare combination: a book that feels alive on the page and rich for later consideration.”

–Bethanne Patrick, The Washington Post

Deep Dive: Brit Bennett on place, isolation, and what it means to be good

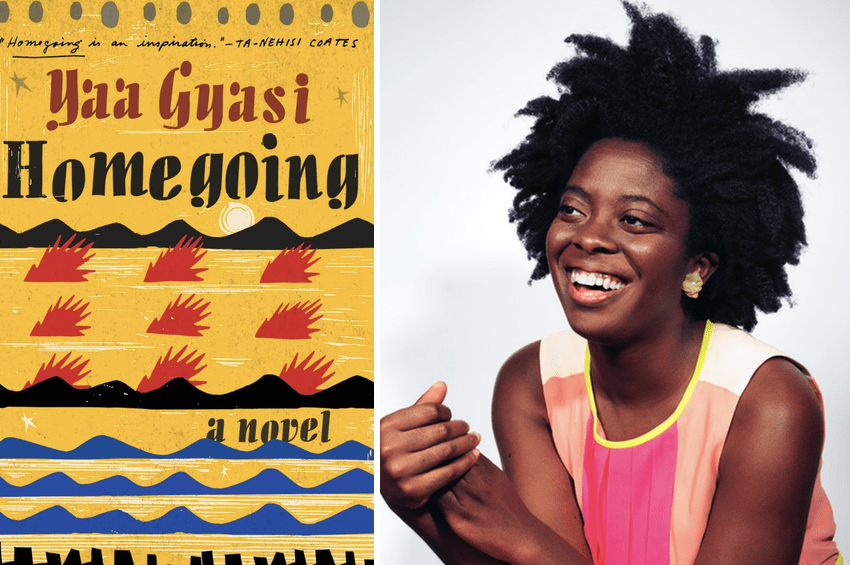

Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing

“[Gyasi is] asking us to consider the tangled chains of moral responsibility that hang on our history. This is one of the many issues that Homegoing explores so powerfully … [the] structure—essentially a novel in linked stories—places extraordinary demands on Gyasi. Each chapter must immediately introduce a new setting and new characters making fresh claims on our engagement. (The family tree at the front of the book is an invaluable reader’s crutch.) But the speed with which Gyasi sweeps across the decades isn’t confusing so much as dazzling, creating a kind of time-elapsed photo of black lives in America and in the motherland … Gyasi, who is just 26 and reportedly received more than $1 million for this book, has developed a style agile enough to reflect the remarkable range of her first novel … truly captivating.”

–Ron Charles, The Washington Post

Deep Dive: Read an excerpt from Homegoing

Greg Jackson, Prodigals

“The writing in Greg Jackson’s first book of stories, Prodigals, is so bold and perceptive that it delivers a contact high. You know from the first pages that, intellectually, you’ve climbed into a high-performance sports car. Only one question remains: Will the author smash it into a tree? … Best of all there’s that sense—only the excellent ones give it to you—that whatever topic the author turns his mental LED lights toward will be powerfully illuminated.”

–Dwight Garner, The New York Times

S. Li, Transoceanic Lights

“Although the story is an intimate portrait of the Chinese immigrant experience, it manages to become larger than that in scope, appealing to readers of any generation, age, and cultural background as a masterful bildungsroman. Throughout the overarching linear narration, Li deftly moves between spaces (America and China), times (the 1980s and the 1990s, it seems), and perspectives (various members of the three Chinese families featured) … This is not a cliché story by any means. There is no hero, no ending of success for the protagonists, or lessons of failure for the antagonists. But what Li accomplishes, as Lahiri and others have done before, is to put in stark relief the continuing social, emotional, and psychological consequences of the Faustian bargain struck when making the decision to leave one’s country to come to another.”

–Paul Vicary, Portland Book Review

Thomas Pierce, Hall of Small Mammals

“Like Pierce’s best work, it’s a commentary; but more important, it’s an experience for the reader, who warms her hands at the fire … It will be tempting, but hard, for readers to choose a favorite among the stories here … The stories have that merry, postmodern humor, but also a classical love of real human emotion … In Pierce’s work, there is a deep marriage between the two [reality and imagination], a vital connection and a natural partnership.”

–Rebecca Lee, The New York Times Book Review

Deep Dive: Read an excerpt from Hall of Small Mammals

2015

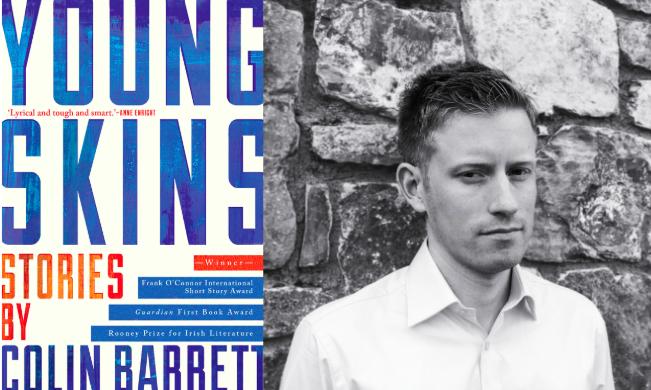

Colin Barrett, Young Skins

“Barrett evokes the lives of his young characters—bouncers, petrol station attendants and minor criminals—with great skill, describing sensitivity and harshness in a way that doesn’t overdo either side of that equation … Barrett doesn’t impose these meanings. Rather his stories invite second readings that—the mark of really good work—seem to uncover sentences that weren’t there the first time around. Chekhov once told his publisher that it isn’t the business of a writer to answer questions, only to formulate them correctly. Throughout this extraordinary debut, but particularly in the excellent stories that bookend it, Colin Barrett is asking the right questions.”

–Chris Power, The Guardian

Deep Dive: Read a story from Young Skins

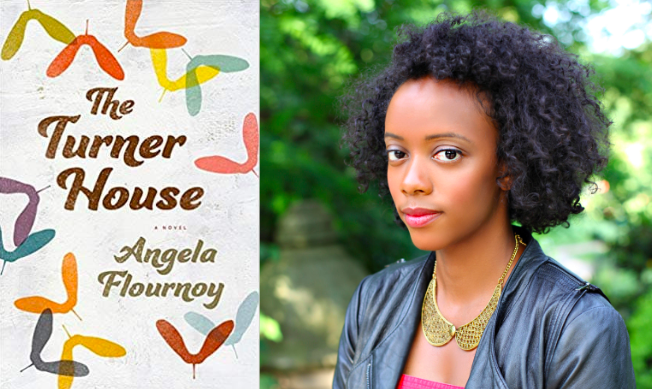

Angela Flournoy, The Turner House

“What is most exciting about Angela Flournoy’s debut novel, The Turner House, is that while history is everywhere in it—haunting its characters, embedded in the walls of the titular house and in the crumbling streets of Detroit—the book tingles with immediacy. Flournoy has written an epic that feels deeply personal … In the end, it is Flournoy’s finely tuned empathy that infuses her characters with a radiant humanity.”

–Leigh Haber, O, The Oprah Magazine

Deep Dive: Angela Flournoy on writing the experience of gentrification

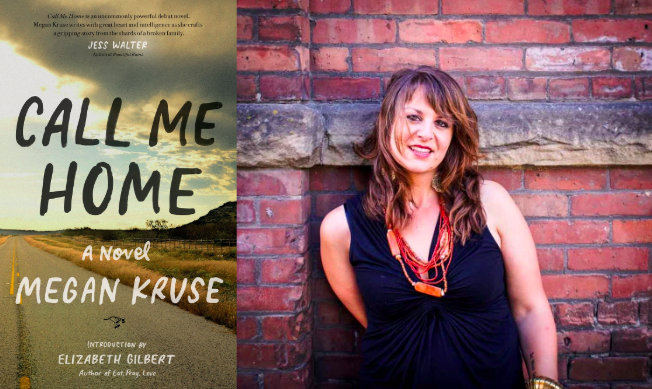

Megan Kruse, Call Me Home

“Megan Kruse’s monochromatic debut novel, Call Me Home, packs quiet power … Watchful Lydia is arguably the star of the novel and her passages are gorgeously smart and sad, but Jackson’s chapters garner the most time, and his story is an intriguing one … Kruse’s skillful language and unusual story construction make for an intriguing meditation on safety, survival, love, and the bonds of blood.”

–Sara Rauch, Lambda Literary

Tracy O’Neill, The Hopeful

“…a literary deep-dive into the ravaging effects of a teen’s pursuit of perfection as a competitive figure skater … Ali’s narration is a cross between Susanna Kaysen and Holden Caulfield—beautiful, observant, and articulate, but we are suspicious of the unreliable nature … this works in the story’s favor, as it illustrates how lost the narrator is in her own obsession, her disassociation from reality, and her rationalization for her desperate measures … Tracy O’Neill has an interesting debut novel on her hands written with an original literary grace all her own.”

–Lavinia Ludlow, The Rumpus

Deep Dive: Tracy O’Neill on the symbolic heft of Tonya Harding

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, Fra Keeler

“Van der Vliet Oloomi’s debut novel turns out to be a surrealist triumph … This short but substantial novel both celebrates the process of thinking and offers cautions about the perils of our inner monologues. A rare gem of a book that begs to be read again.”

Deep Dive: Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi on family, restlessness, and revolution

2014

Yelena Akhtiorskaya, Panic in a Suitcase

“…brilliant and often funny … Though the book leans on autobiography—Ms. Akhtiorskaya, who was born in 1985, moved with her family from Ukraine to Brighton Beach in 1992—it has been transformed into the kind of fiction that is richer than real life. Whatever personal details she has marshaled have been charged with consistently imaginative language and great verve … Panic in a Suitcase is composed of leisurely episodes, but Ms. Akhtiorskaya’s prose keeps the pace moving as quickly as any suspenseful plot could. On every page, she writes about people and things with close attention … This sparkling debut, though it stays close to home, suggests she can roam wherever she’d like.”

–John Williams, The New York Times

Deep Dive: Read an excerpt from Panic in a Suitcase

Alex Gilvarry, From the Memoirs of a Non-Enemy Combatant

“The memoir genre has become reflexively controversial, and Alex Gilvarry’s fiction debut leverages its dark side to the fullest … Researched fiction often grows clumsy with excessive fact, but Gilvarry knows how to immerse his readers without harping on the trivial. Described in Boyet’s voice, both fashion and political imprisonment become acutely vivid … It’s easy to draw parallels between Gilvarry and Gary Shteyngart—there’s the ironic tone, the sharp social commentary, the stream-of-consciousness narration … Intricately researched and expertly crafted, Memoirs is a poignant reminder of what contemporary fiction ought to be. You will laugh, but you’ll do so nervously, sitting at the edge of your seat.”

–Ana Grouverman, The Rumpus

Deep Dive: Alex Gilvarry on the toxic competitiveness of writers

Phil Klay, Redeployment

“Klay succeeds brilliantly, capturing on an intimate scale the ways in which the war in Iraq evoked a unique array of emotion, predicament and heartbreak. In Klay’s hands, Iraq comes across not merely as a theater of war but as a laboratory for the human condition in extremis … Each story calls forth a different dilemma or difficult moment, nearly all of them rendered with an exactitude that conveys precisely the push-me pull-you feelings the war evoked: pride, pity, elation and disgust, often pulsing through the same character simultaneously … Klay has a nearly perfect ear for the language of the grunts—the cursing, the cadence, the mixing of humor and hopelessness. They are among the best passages in the book, which, unfortunately, are unfit for a family newspaper.”

–Dexter Filkins, The New York Book Review

Valeria Luiselli, Faces in the Crowd

“Faces in the Crowd is a haunted book—the stories the characters tell are like the pieces of a broken mirror we might try to treat as a puzzle, something manageable that can be reassembled, but the pieces never fit. There are too many duplicates and holes, too much white space on the page. Unlike other novels that have a similar fragmentary or experimental structure, this novel never gets bogged down by unnecessary opaqueness or frivolous difficulty. There’s a hardened clarity to Luiselli’s prose, which makes reading each of her sentences a dark, quiet pleasure … Faces in the Crowd is the greatest of all things: a novel meant to be reread. It’s not until the latter half of the book, once the complexities of the structure are fully apparent, that the mystery Luiselli has crafted gains exponential, existential force, which we can then trace to very first pages.”

–Alexander Kalamaroff, The Rumpus

Deep Dive: Valeria Luiselli on the best journalism in Latin America

Kirstin Valdez Quade, Night at the Fiestas

“…haunting and beautiful … This is a variety of beauty too rare in contemporary literature, a synthesis of material and practice and time and courage and love that must have cost its writer dearly; it’s not easy to be so vulnerable so consistently. Quade attempts, page by page, to give up carefully held secrets, to hold them up to the light so we can get at the truth beneath, the existential truth.”

–Kyle Minor, The New York Times Book Review

2013

Molly Antopol, The UnAmericans

“[A] deft collection … it seems as if the decision to spread out geographically allowed her to look at the fragile connections that exist between people in and out of couples and families. The stories are as satisfying as individual novels. They often keep going right past the point where you thought they would end … They’ll make you nostalgic, not just for earlier times, but for another era in short fiction. A time when writers such as Bernard Malamud, and Issac Bashevis Singer and Grace Paley roamed the earth … beautiful and appealing.”

–Meg Wolitzer, NPR

Deep Dive: Read Molly Antopol’s O. Henry Prize-winning story “My Grandmother Tells Me This Story”

NoViolet Bulawayo, We Need New Names

“The kids’ names give you a clue of how wanted they are at home. There’s a Bastard and Godknows. One girl is pregnant at 11. They wear cast-off T-shirts given to them by aid workers, advertising brands they can’t afford and colleges they’ll never attend. Poignantly, they know their dreams of escape are lined with tin … Chapter by chapter, Bulawayo ticks off the issues that a state-of-the-nation novel by an African should cover—the hypocrisies of the church, elections, the AIDS epidemic, political violence—and beats some subtlety back into them with the hard true sound of Darling’s voice … With fury and tenderness, she has made a linguistic bridge between here and there, a journey her heroine charts in this phenomenal tale with the gallows humor of a girl who knows how far down it is when things fall apart.”

–John Freeman, Minneapolis Star-Tribune

Amanda Coplin, The Orchardist

“Amanda Coplin’s somber, majestic debut arrives like an urgent missive from another century. Steeped in the timeless rhythms of agriculture, her story unfolds in spare language as her characters thrash against an existential sense of meaninglessness … Coplin’s saga of a makeshift family unmoored by loss should be depressing, but, instead, her achingly beautiful prose inspires exhilaration. You can only be thrilled by a 31-year-old writer with this depth of understanding … Angelene’s final epiphany equals in stark grandeur similar scenes in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights and Pat Barker’s Another World—heady company for a first novelist, but Coplin’s talent merits such comparisons.”

–Wendy Smith, The Washington Post

Daisy Hildyard, Hunters in the Snow

“Daisy Hildyard’s skill has been to weave all the disparate elements into a seamlessly structured and utterly absorbing investigation of our relationship with the past … It’s presumably the fruit of years of roaming through libraries, examining dusty tomes in second-hand bookshops, and the novel conveys the delight of these old-fashioned pleasures, which is why I loved it. Despite the apparently random associations of the narrative, it’s all so beautifully controlled … Here is a novel so rich in texture it deserves many rereadings.”

–Rachel Hore, Independent (UK)

Merritt Tierce, Love Me Back

“When I started reading Merritt Tierce’s debut novel about a self-destructive waitress, by page four I thought Tierce had penned the greatest restaurant book on earth … From the get-go, it’s clear that this is an author who understands the perverse power that comes from allowing our female bodies to be used. Which is to say: this is a book that talks about how powerful and fragile and dangerous it is to be a woman living, working, and reproducing in the world we know today … In a book so visceral and vitriolic that Tierce’s insights come at you like thrown acid, it’s hard to pin down the one thing that should make you read it. But for the mothers out there, Tierce has captured the frantic desire to both protect and expel these creatures that come out screaming, red-faced from us, expecting the whole world … If we can wish one thing for Marie and her creator, Merritt Tierce, it’s that this book will put the term ‘unlikeable character’ to rest. I didn’t like this bone-worked, maddening, cavernous mother, I loved her all the way to her rotted core.”

–Courtney Maum, Electric Literature

Deep Dive: Merritt Tierce on what to read if you care about access to abortion in Trump’s America

2012

Jennifer duBois, A Partial History of Lost Causes

“In Dubois’s terrific debut, Aleksandr Bezetov arrives in Leningrad to study chess on the day of Stalin’s centenary celebration in 1979 and meets two men who publish a dissident journal called A Partial History of Lost Causes … In urgent fashion, Dubois deftly evokes Russia’s political and social metamorphosis over the past 30 years through the prism of this particular and moving relationship.”

Deep Dive: Jennifer duBois on when a first-person narrator sneaks into your story

Stuart Nadler, The Book of Life

“While each story of Stuart Nadler’s The Book of Life centers on a different man, the man is always fundamentally the same. He has lost something, is looking for something, and is hemmed in by the inevitable complications of his relationships … Nadler also places emphasis on each man’s connection to Judaism, which appears as an anchor in the midst of the chaos of their lives. For the characters, no matter what occurs in the stories that compose The Book of Life, it is presumed that there is something larger beyond themselves; something none of these men seem to have found … Nadler shows that a book of life is not grandiose; it can be simply an amalgam of life’s banalities.”

–Megan Hall, Full Stop

Deep Dive: Stuart Nadler’s ode to the darlings he’s drowned

Haley Tanner, Vaclav & Lena

“…[A] wonderful and wrenching debut novel … Whimsical love stories are tough to pull off. But as in the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, vibrant characters, believable romance and dark undertones make for a moving tale. The book’s contrast between childhood fantasy and the grim world outside tamps down the cutesiness. It helps that Ms. Tanner is such a strong storyteller, and her distinctive voice—winsome without being dopey—engulfs you immediately.”

–Susannah Meadows, The New York Times

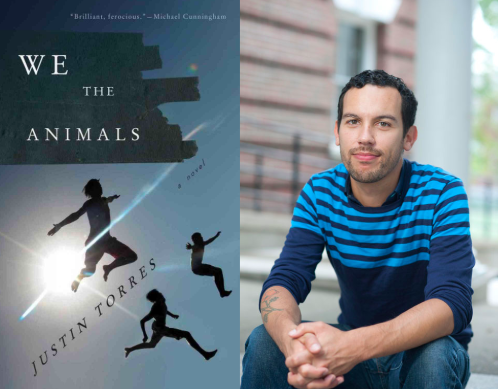

Justin Torres, We the Animals

“It’s rare to come across a young writer with a voice whose uniqueness, power and resonance are evident from the very first page, or even the very first paragraph … a slender, tightly wound debut novel by a remarkable young talent … readers, even those who don’t go on to love everything about the book, will have little choice but to conclude that they are hearing something new, something strong and something very self-assured … Without the benefit of a plot’s forward momentum, Torres must ask his prose and characterization to do the heavy lifting. He has a special talent for instilling banal events with epic import … Justin Torres is a tremendously gifted writer whose highly personal voice should excite us in much the same way that Raymond Carver’s or Jeffrey Eugenides’s voice did when we first heard it.”

–Jeff Turrentine, The Washington Post

Claire Vaye Watkins, Battleborn

“The most notable feature of Battleborn, the first story collection by Claire Vaye Watkins, is its physical landscape, especially as it affects the people who stake their claims on its inhospitable terrain … Whether Watkins casts a backward glance (as in ‘The Diggings,’ a 60-page novella set during the 1848 gold rush) or a contemporaneous one (‘The Past Perfect, the Past Continuous, the Simple Past,’ which begins: ‘This happens every summer. A tourist hikes into the desert outside Las Vegas without enough water and gets lost’), her vision is brutally unsentimental. Characters dig themselves into holes—literal or figurative — and are not explicitly rescued. If they survive it’s by the same means as they’ve so far endured: stubbornness, luck and a slim strand of hope … Readers will share in the environs of the author and her characters, be taken into the hardship of a pitiless place and emerge on the other side—wiser, warier and weathered like the landscape.”

–Antonya Nelson, The New York Times

Deep Dive: Claire Vaye Watkins on how to escape your hometown

2011

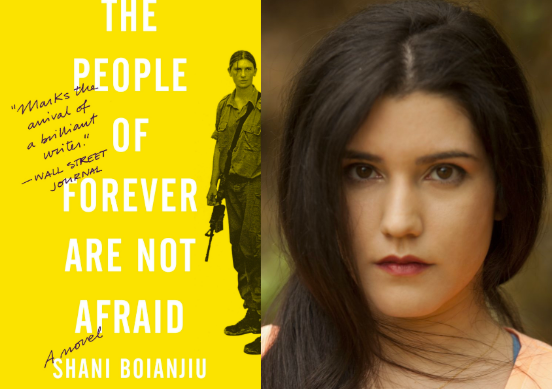

Shani Boianjiu, The People of Forever Are Not Afraid

“Boianjiu’s prose has a flat, harsh glare that can seem benumbing at first but evokes the deadening that comes of constant war. Part of this impressive book’s power is that it manages to re-create and rupture that numbness, war’s tedium and the damage it does to memory, intimacy, thought and affection … Boianjiu makes clear that among the casualties of war is meaningful communication itself … She also upends the cliche that war builds camaraderie … It’s a tribute to Boianjiu’s artistry and humanity that she portrays those on both sides of the barbed wire as loved and feared. The People of Forever Are Not Afraid is a fierce and beautiful portrait of the damage done by war.”

–E.J. Levy, The Washington Post

Danielle Evans, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self

“Danielle Evans’ Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self is a remarkable short-story collection in a good year for short-story collections. Every story takes on its own life, all her characters live rich and complicated lives, and the plotting never grows too predictable or unfocused … She has a unique gift for zeroing in on moments of crisis so precise that they illuminate almost all corners of her protagonists’ lives, and her gift for unveiling crucial backstory never lets these tales get too exposition-heavy … Her sentences stake out claims on the edge of possibility, of things that are almost about to happen, and her stories ring with vivid, unexpected metaphors.”

–Emily Todd VanDerWerff, A.V. Club

Deep Dive: Danielle Evans on why a writer should move to Baltimore

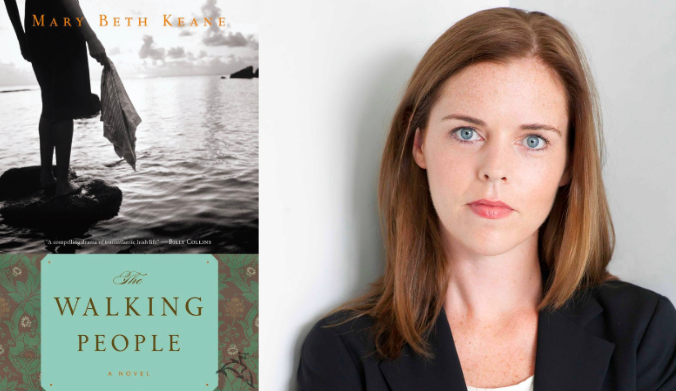

Mary Beth Keane, The Walking People

“…a richly moving first novel about Irish immigration to America in the late 20th century … Keane gives her characters range and complexity so that there are no victims or villains. Sometimes heart-wrenching, sometimes joyous and tender—one of those stories that lingers in the reader’s memory as a lived experience.”

Deep Dive: Mary Beth Keane on realizing she was writing a book

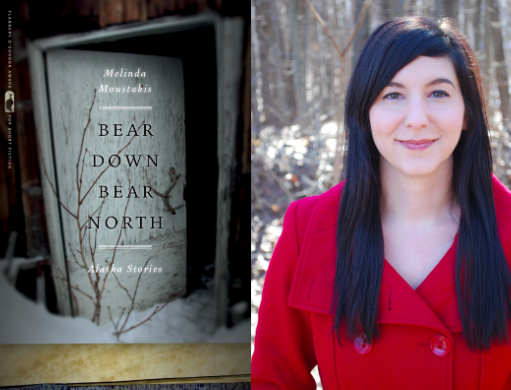

Melinda Moustakis, Bear Down, Bear North: Alaska Stories

“In a year filled with more than a few bleak, strong debut anthologies with a guiding location…Melinda Moustakis’ debut collection, Bear Down Bear North: Alaska Stories might be the strongest of them all. A series of linked stories set around the homesteads and rural cabins of Anchorage, Alaska, this slim volume delivers a powerful look into the lives of three generations and how an unforgiving environment wears them down as they grow … This is a memorable debut for its conviction, as unforgiving in its portraits as the environment Moustakis finds both beautiful and destructive.”

–Kevin McFarland, A.V. Club

John Corey Whaley, Where Things Come Back

“It’s such a unique read combining so many different aspects of human life, putting them together in such a way that you’re left feeling resolved when finishing it somehow … the way in which John Corey Whaley writes this book is fantastic. It’s so accessible and fast paced, I got into it and couldn’t stop until I’d finished the last page. It’s addictive … It’s given me so much food for thought that I know I’ll be thinking about this book months, maybe even years, from now.”

–Abby O’Reilly, The Guardian

2010

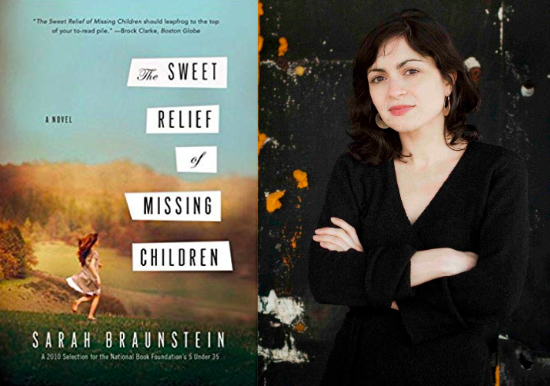

Sarah Braunstein, The Sweet Relief of Missing Children

“At more than 350 pages, The Sweet Relief of Missing Children is a substantial debut novel, but movement is fierce and swift … Braunstein’s writing is richly poetic, bringing to mind the prose of Pulitzer Prize-winner Elizabeth Strout … This is a novel you won’t want to put down. These are characters you won’t want to stop rooting for.”

–Brian Hieggelke, New City Lit

Grace Krilanovich, The Orange Eats Creeps

“…beautiful and deranged … Trying to capture the experience of a character on the brink of insanity is daring and rarely successful. When it works—think William Burroughs at his best—readers must be able to encounter the narrator’s skewed psychology without becoming lost amid the hallucinatory logic. The Orange Eats Creeps performs this tricky balancing act … a wild, and often terrifying, inner world.”

–Adam Wilson, Bookforum

Téa Obreht, The Tiger’s Wife

“Téa Obreht’s stunning debut novel, The Tiger’s Wife, is a hugely ambitious, audaciously written work that provides an indelible picture of life in an unnamed Balkan country still reeling from the fallout of civil war … It’s not so much magical realism in the tradition of Gabriel García Márquez or Günter Grass as it is an extraordinarily limber exploration of allegory and myth making and the ways in which narratives reveal—and reflect back—the identities of individuals and communities: their dreams, fears, sympathies and hatreds … As Ms. Obreht parcels out chapters of these two fables, she gives us vivid portraits of Gavo, the tiger’s wife and other fairy-tale-like characters. By peopling The Tiger’s Wife with such folkloric characters, alongside more familiar contemporary types, Ms. Obreht creates an indelible sense of place.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

Deep Dive: Téa Obreht and Thomas McGuane in conversation

Tiphanie Yanique, How to Escape from a Leper Colony

“What is at stake in these stories is not only a matter of racial and ethnic identity, however; How to Escape is also concerned with boundaries and divisions more generally … One of the chief pleasures of reading this collection is experiencing the range of characters and voices that Yanique offers. She is capable of evoking a sense of a full life in just a few pages, and she successfully negotiates extremely varied times, places, and cultures in the space of a single story.”

–Rebecca Hussey, Necessary Fiction

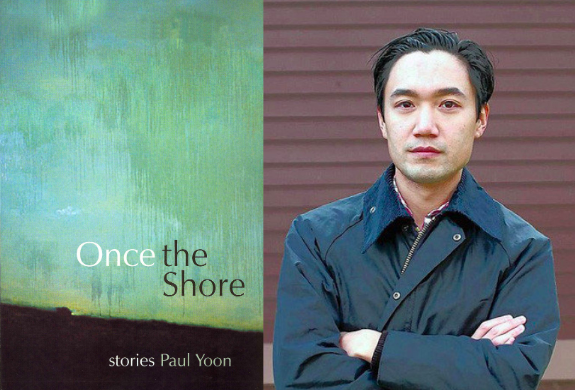

Paul Yoon, Once the Shore

“In Paul Yoon’s first story collection, Once the Shore, characters move in a haunted stillness … Yoon’s prose is spare and beautiful. He can describe the sea more ways than seem possible without losing freshness, and his characters’ world is often quietly dazzling … Yet the beauty of these stories is precisely in their reserve: they are mild and stark at the same time … Once the Shore is the work of a large and quiet talent.”

–Joan Silber, The New York Times

Deep Dive: Read a story from his collection, The Mountain

2009

Ceridwen Dovey, Blood Kin

“…precise and terrifying … while the novel’s spell lasts, it can feel like the earliest, exhilarating days under a new administration, when a pliant populace is eager and willing to follow wherever a confident leader directs us … even if we had no idea what life was like under their equally despotic reigns, we could immediately recognize the brutality from Dovey’s pitch-perfect renderings of her three narrators’ daily lives and routines, each one a microscopic marvel of sublimated aggression … a muted success … Dovey’s ultimate lesson, that nature and mankind abhor a power vacuum, may be a bleak one, but she presents her case so meticulously and relentlessly that you’ve got to respect her authority.”

–Dave Itzkoff, The New York Times

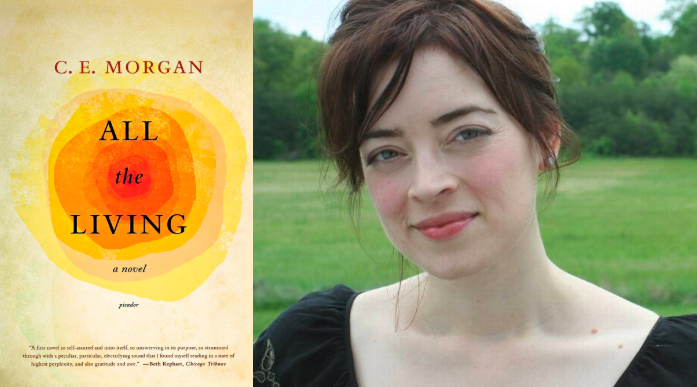

C.E. Morgan, All the Living

“Morgan writes near-perfect prose, whether she’s describing the mountains of Kentucky or sex or the acute longing for consolation that brings impoverished farmers together at church each Sunday. If we can all agree that it’s a struggle to write well about sex, or about God, then we’d all do well to spend some time with C.E. Morgan’s novel, one of the most astonishing fiction debuts of recent years … While the dangers posed to the farm ostensibly drive the plot forward through the long, parched summer—and Morgan’s evocative language is perhaps at its sharpest and clearest when describing the unforgiving landscape that surrounds Aloma—the book is essentially a study in loneliness … This first novel is written with all the deceptive simplicity of a poem and yet the incantatory resonance of a prayer.”

–Angelica Baker, Tin House

Lydia Peelle, Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing

“Peelle is an impressive prose stylist who focuses on human beings as members of communities, and the stories in Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing show how impoverished our collective life becomes when greed, neglect, and carelessness characterize human behavior … Peelle doles out words as if they were scarce commodities, producing elliptical tales in which the occasional metaphor lights up an entire landscape … Fine as Peelle’s dialog is, it’s often the small gesture that proves most revealing of character … Peelle loses me only when she becomes overtly elegiac—those times I hear the violins whining plaintively in the background. Others may find some stories a tad too quiet. But her genius is to make scurrilous ne’er-do-wells into likeable, sympathetic characters.”

–Karen Laws, The Rumpus

Deep Dive: Lydia Peelle on being a mother and a writer in a time of war

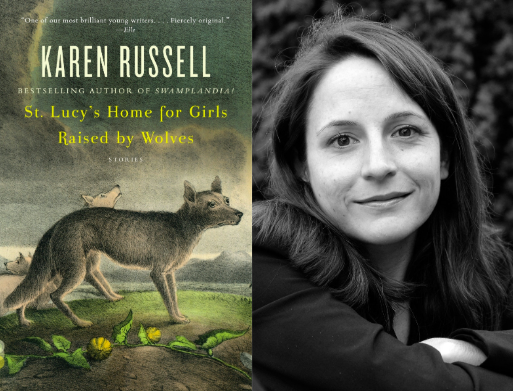

Karen Russell, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves

“Karen Russell’s stories are unnerving, darkly funny, and immensely enjoyable. Their standard recipe takes a common coming-of-age theme…folds it into a surreal situation…and tops it off with superb, efficient sentences. Mix well and you’ve got one of the strongest debuts in recent memory … Moving skillfully between the banal and the extraordinary—a dingy dining room one minute, secret underwater caves the next—Russell blurs the boundaries between the real and the surreal until we become hyperaware and suspicious of every detail. It’s an effect that lasts even after you set the book down … These haunting stories confidently eschew tidy, ‘life’s pretty swell after all’ resolutions. Instead, Russell concludes them with harrowing abruptness, showing how childhood, for all its supposed freedom and ease, can in fact be painful, dangerous, and rife with near-fatal miscalculations.”

–Thomas Haley, The Believer

Deep Dive: Karen Russell on America’s housing catastrophe

Josh Weil, The New Valley

“The last novella, ‘Sarverville Remains,’ is the longest and the best. The loner this time is the 30-something Geoffrey Sarver, a mentally disabled gas station attendant who finds himself at one corner of an unlikely love rectangle … A hippie commune appears briefly in each novella, the only place they intersect, and it reveals something fundamental about each main character … Read back to back to back, these novellas form a triptych—detailed works in their own right, they offer more than the sum of their parts when taken together. Weil meticulously imagines people and their histories, and presents them as a product of their places. This is perhaps the hardest thing for a fiction writer of any age, working in any form, to accomplish.”

–Anthony Doerr, The New York Times Book Review

Deep Dive: Josh Weil on the ways in which a novel can fail like a marriage

2008

Matthew Eck, The Farther Shore

“…one of the few creative works about the Somali conflict that doesn’t center on the downed Black Hawk helicopter and the 18 Army Rangers and Delta Force commandos who died trying to capture the warlord Mohammed Farrah Aidid … Eck has served in the military in Somalia, and the strongest aspect of this novel is his ability to bring us straight into the devastation, all its sights and sounds whirling around us as they whirl around Stantz and his comrades … Eck’s writing could also use more rhythm, and more emotional emphasis. Sometimes awkward and stilted, his prose can stumble over itself … The mental landscapes Eck’s characters inhabit are mostly two-dimensional, and the reader keeps hoping to see both the Americans and the Somalis as more than mere victims of circumstance.”

–Uzodinma Iweala, The New York Times Book Review

Keith Gessen, All the Sad Young Literary Men

“Of the three young men, Keith is both the most immediate, framing the episodic novel with his affably intimate first-person narrations, and the least clear … This Keith is a vortex of thoughts, an optic nerve of observations, a summary or catalog rather more than a vividly realized character … Beginning with its risky yet playful title, All the Sad Young Literary Men is a rueful, undramatic, mordantly funny, and frequently poignant sequence of sketch-like stories loosely organized by chronology and place and the prevailing theme of youthful literary ideals vis-à-vis literary accomplishment … The predicament of Gessen’s characters, as it is likely to be the preeminent predicament of Gessen’s generation, is the disparity between what one has learned of history and the possibilities of making use of that knowledge in one’s life … Gessen has captured perfectly the narcissistic ennui of privileged youth for whom self-flagellation is an art form.”

–Joyce Carol Oates, The New York Review of Books

Sana Krasikov, One More Year: Stories

“Like most modern migrants, the characters in these eight stories inhabit both past and present, homeland and new land … One More Year is chiefly about exile and fidelity. Krasikov’s migrantka (they are mainly women) enact two plots: leaving their country and leaving their love(r) … Krasikov’s cast of exiles, refugees and repatriates are also, more fundamentally, people moving in and out of love—or what passes for it. She has written a sensitive book about the economics of relationships: how they can become subtle transactions by people trying to pull off the trick of occupying more than one place and more than one time.”

–Gaiutra Bahadur, The New York Times Book Review

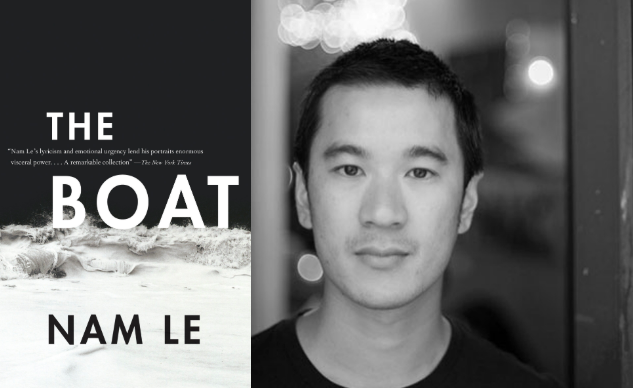

Nam Le, The Boat

“What [the stories] all have in common is that each one portrays its characters in a crisis that reveals resources of courage and resilience even he or she was not aware of. All but one of the stories concern what is arguably the deepest, most complex and most poignant of human relationships: the bond between parent and child … Of all these heartrending stories of pain and loss, the most moving and unforgettable in the collection is ‘Halflead Bay’ … As Faulkner observed, voices like his not only record the human condition but also help us endure and prevail.”

–Michael McGaha, The San Francisco Chronicle

Deep Dive: Nam Le on the violence of world-building

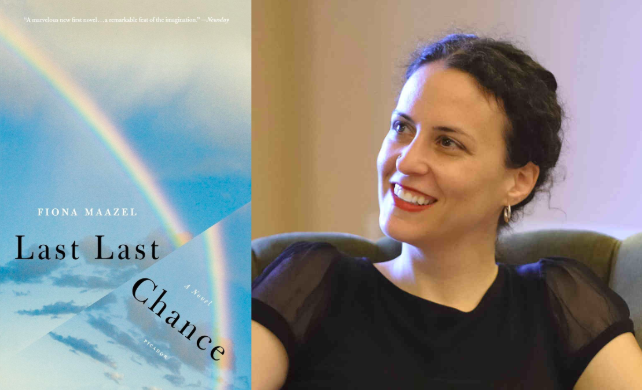

Fiona Maazel, Last Last Chance

“Last Last Chance isn’t your average novel, thanks in no small part to Maazel’s funny, lacerating prose. The book fits squarely in the tradition of novels about the wealthy and dissolute, but ultimately it’s less John Cheever than Denis Johnson—the Denis Johnson of Jesus’ Son, with its drug-addled narrators—though Maazel’s voice is more caffeinated, more fueled by attitude…and more prone to hectoring … Maazel is particularly adept at conveying the desperation of the addict, how everything — even a potentially world-ending plague—is eclipsed by the need for a fix … But Maazel’s novel is most powerful in its quieter, more mundane moments … One instance of absurdism could as easily be exchanged for another; at times the novel loses its sense of inevitability.”

–Joshua Henkin, The New York Times Book Review

2007

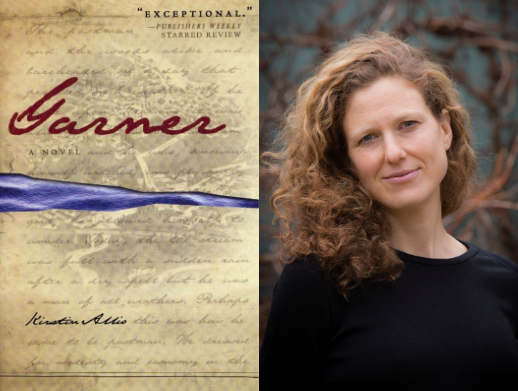

Kirstin Allio, Garner

“As an opening to her first novel, Kristin Allio opts for a quietly stunning revelation, old-fashioned and filmic at once, wherein the body of young Frances Giddens is discovered by the town’s postman in a local brook … If Garner, the town, is the soul of this mystery, then Frances is its spirit … Generically less novel than long scrapbook-poem, this first section is a patchwork—of poetic musings, town-meeting transcripts, dream sequences, lists of native plants, local lore and aphoristic proclamations—which successfully cobbles a sense of the civil ordinances and Puritanical strictures underpinning the town’s mores … It is rare to feel so truly transported by a work of fiction … I dub Garner a masterly, multi-voiced, mood-altering mystery—and a debut so wise, certain, and cleverly empathetic as to seem the work of a sure-footed pro.”

–Heather Birrell, The Believer

Deep Dive: Kirstin Allio on her life in a Buddhist cult

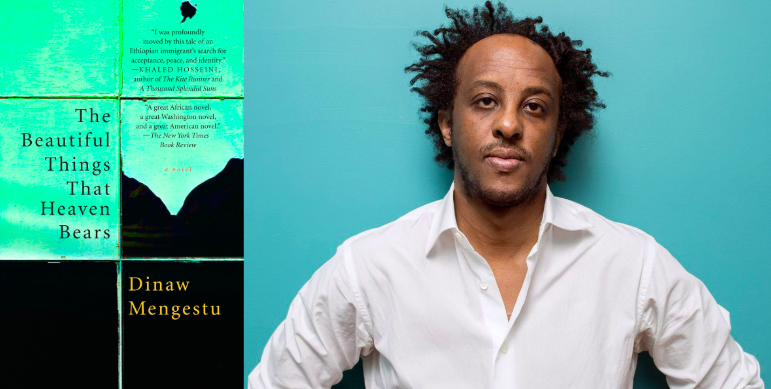

Dinaw Mengestu, The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears

“The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears is about the animate presence of loss, about a man struggling to find traction in his ostensibly current life as proprietor of an ailing Logan Circle grocery store. Almost every page reminds us that ‘departure’ and ‘arrival’ are deceptively decisive words … The deeply felt pain in Mengestu’s novel is offset by the solace of friendship—whether it’s a friendship that hovers on the verge of romance, a friendship between an adult and a child or, above all, the friendships that steady the daily lives of fellow immigrants … Mengestu has a fine ear for the way immigrants from damaged places talk in the sanctuary of their own company, free from the exhausting courtesies of self-anthropologizing explanation. He gets, pitch perfect, the warmly abrasive wit of the violently displaced and their need to keep alive some textured memories—even memories that wound—amid America’s demanding amnesia … It’s rare that a novelist who can comfortably take on knotty political subjects like exile, memory and class conflict is also able to write with wisdom, wit and tenderness about the frisson of romance … A great African novel, a great Washington novel and a great American novel.”

–Rob Nixon, The New York Times Book Review

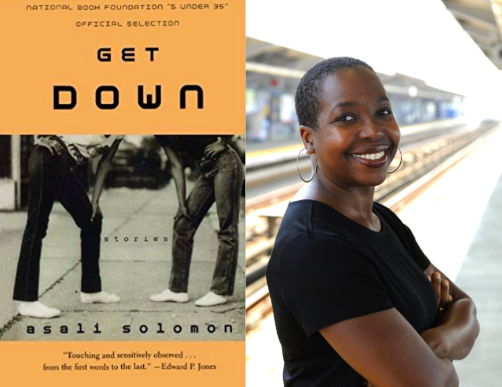

Asali Solomon, Get Down: Stories

“Asali Solomon’s Get Down is a book that understands the degree to which race and racial identity are so often about performance … Solomon’s characters are aware of the ways in which they are weird and quirky and lonely and awkward and searching and human. They are aware of the ways in which they are never far from their histories, and never free from the prisms through which they are viewed … The thread that ultimately ties these stories together, and these characters to readers, is the raw desire for genuine human connection in the face of everything—race included—that seems determined to sabotage it.”

–Danielle Evans, NPR

Anya Ulinich, Petropolis

“It’s refreshing, then, to see something like a new American dream appear in Anya Ulinich’s first novel, Petropolis. Here, it’s no longer a matter of material success, or even educational opportunities, but about finding a place for one’s misfit heart … Sasha is a lonely, pudgy girl—an ugly duckling born to a swan of a mother. This near-but-not-quite acquiescence to cliche runs throughout the book but, luckily, Ulinich has a wry sense of the absurd that usually turns the commonplace on its head … Ulinich has a keen literary sensibility that brings forth the pathos of her heroine’s quest without indulging in bathos … Easy sentimentality is also thankfully avoided … The absurdity of these preconceptions, and the freedom to escape from them, is what shapes Ulinich’s narrative and what forms its great optimism.”

–Andrea Thompson, The San Francisco Chronicle

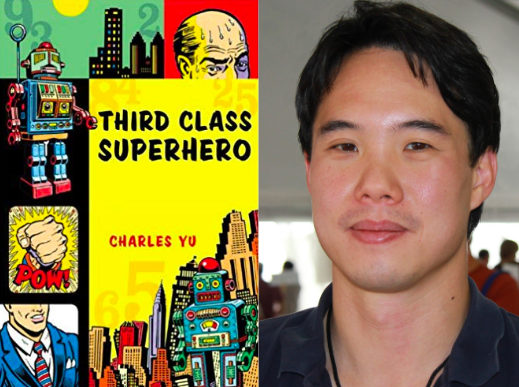

Charles Yu, Third Class Superhero

“Issues of identity and insecurity simmer throughout Yu’s debut collection, an imaginative excursion into the burrow Kafka built … Yu flirts with formal experimentation…but tempers his fantastical constructions with level prose … There is abundant humor, though, and Yu allows the reader to feel pathos without patronization; a neat trick, in a compulsively readable collection.”

2006

Amity Gaige, O My Darling

“Love, marriage, the whole damn thing—all spanned in a witty, tender first novel … Gaige’s beguilingly offbeat voice and appealing mix of humor and insight offer continual pleasures, and her story, woven together with that of the house, reaches high. Each chapter follows the discrete shape of a short story while also building on the troubling notion that there are indeed ghosts abroad … Conventional action is relatively minor … But the shifts in mood and the variations in the couple’s power balance are just as telling … In the final pages, Gaige’s usually unerring if unpredictable sense of narrative true north wavers, and chapters become ragged. Despite a final soft-centered swerve, however, the impression overall is of a limpid style and the peeling away of the comedy of intimacy to expose isolated souls.”

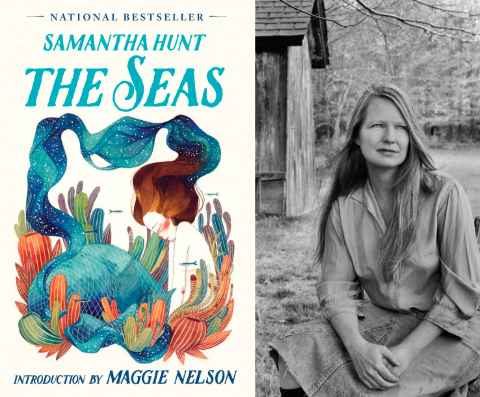

Samantha Hunt, The Seas

“The true power of this novel is in the young woman’s narration. She is not a victim. She is never passive. Her sexual desires are bold and sharp. In an exceptionally singular voice, she dreams vividly of what she wants … It’s hard to imagine that a book so brief could tackle the Iraq war, grief over the loss of a parent, the longing for freedom, an enthrallment with the ocean, loneliness, sexual awakening, faith, and etymology, all in less than 200 pages, but Samantha Hunt has done it, and done it well. The conciseness of the novel is part of what makes it so artful … We root for her [the narrator], and wish—up until the very last page—that she will grow a tail and escape into the ocean.”

–Sara Cutaia, The Chicago Review of Books

Deep Dive: Samantha Hunt on the ghosts of Brooklyn past

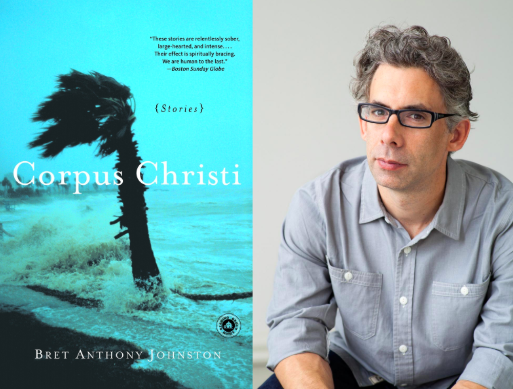

Bret Anthony Johnston, Corpus Christi: Stories

“In his promising debut collection, Johnston travels through time and across socioeconomic divides to present a series of nuanced portraits of middle-aged, middle-American loneliness in all its permutations … Johnston’s Corpus is America in microcosm. But it is the emotional landscape that interests the author, not the physical, and, without lapsing into sentimentality, he evokes a peculiarly American brand of abject loneliness and tentative optimism.”

Rattawut Lapcharoensap, Sightseeing

“It’s the distance between that outsider’s paradise and the native’s often grim reality that Lapcharoensap shows us in his tales, so tenderly crafted and beautifully realized that they’ll snuggle up behind your heart and stay there for a long time … The first five stories are all told from the point of view of young boys with similar voices, and this has a comforting effect. One of the difficulties in reading a short story collection is that, just as you get used to a particular voice, it abruptly changes, and Sightseeing provides a nice change from typical collections for that reason. Lapcharoensap’s boy narrators are so fully realized that you want to stay with them, even when the towns, back stories and plots around them change.”

–Priya Jain, Salon

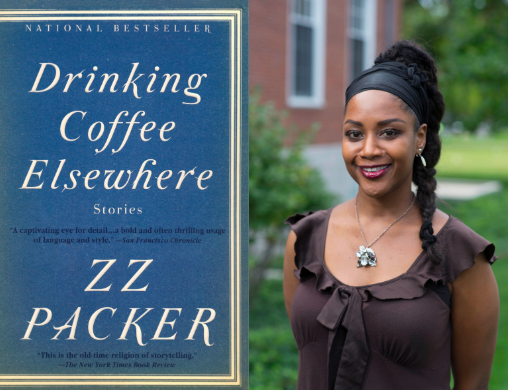

ZZ Packer, Drinking Coffee Elsewhere

“There is an apparent ease of composition and confidence of direction. There is enough texture of detail, colour, cruelty and sensibility to give the writing that elusive feeling of reality. But the winning component is Packer’s authorial voice: uncompromising, funny, angry without the obsession, political without tedium, intensely human, peppered with astonishing moments of poetry … This is a book full of journeys and escape, of characters displaced or alone, who often find that their destinations pose even more profound threats to their survival … While Packer does seem over-preoccupied with black and white, she allows her lens to take in the grey areas between. In her darting through history and the present, she poses that essential question: how much has really changed? … Serious and contentious, she never loses hold of the craft and delight of storytelling.”

–Diane Evans, The Independent (UK)