Somehow it’s late September, which means there’s a chill in the air and just about everything seems to be careening away from the delicious torpor of summer. But it’s not all bad news. September is also National Translation Month, and exciting things have been happening all around. For instance: Words Without Borders announced that Chad W. Post will receive this year’s Ottaway Award for the Promotion of International Literature. Chad has been a champion of literature in translation for more than a decade, from founding and running Open Letter Books, to establishing the Best Translated Book Award and blogging/podcasting about translation, maintaining the invaluable translation database, and… and… and… So: three cheers to him and to the wonderful WWB. (Check out this month’s special issue on writing from Georgia.)

Then there was the announcement of the longlist for the inaugural* National Book Award for Translated Literature. I was thrilled to see my translation of Roque Larraquy’s Comemadre alongside widely recognized works like Yoko Tawada’s The Emissary (tr. Margaret Mitsutani) and Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights (tr. Jennifer Croft), and books I can’t wait to check out, like Dunya Mikhail’s The Beekeeper (tr. Dunya Mikhail and Max Weiss) and Perumal Murugan’s One Part Woman (tr. Aniruddhan Vasudevan).

Anyway, whether because of the frantic rhythm of fall or the waning daylight hours, my mind turned this month to compact and often unsettling worlds that unfold in a single sitting. Here’s a mix of recent favorites and titles I’m still recommending as the years go by:

The Emissary by Yoko Tawada

Translated from the Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani

New Directions (April 2018)

In the wake of an ecological disaster that has turned its soil to poison and generated extraordinary mutations in its flora and fauna, Japan finds itself cut off from the rest of the world and on the brink of societal collapse. Children are born so weak they can barely muster the energy to eat the food they need to survive, while the elders of the community outlive generation after generation of their descendants. Against this backdrop, the elderly but robust Yoshiro is charged with caring for his great-grandson, Mumei, a sweet and exceptionally intuitive young boy who might just be the envoy this desperate society needs. In the barren landscape of this slim novel it isn’t just the population that’s dying off: language itself seems in danger of extinction, due in large part to the tariffs and restrictions on foreign words since Japan closed its border—a situation painfully reminiscent of the current pandemic of xenophobia and the soggy jingoism of Freedom Fries. All told, The Emissary is a complex and startling dystopian fiction that, in Mitsutani’s translation, skates deftly between the apocalypse and the kitchen table, bleak prophecy and cheery aphorism. This is a strange world indeed, and I didn’t want to leave it.

Double take: Andrew Hungate on the work and its context, over at Words Without Borders.

Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera

Translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman

And Other Stories (March 2015)

I can’t imagine what could possibly be turning my mind to borders these days, but reading The Emissary reminded me of another remarkable short work—one of my favorite books of recent years, in fact, which I teach/push/praise every chance I get. Together with The Transmigration of Bodies (2016) and Kingdom Cons (2017), the Best Translated Book Award-winning Signs is part of what could be described as a border trilogy: narratives centered on the circulation of bodies, and violence, back and forth between Mexico and the United States (though Herrera draws his narrative maps with allusions rather than specific place names). This brief novel—recently adapted for the stage at the 2018 Edinburgh International Book Festival—begins with the earth literally falling out from under the feet of its protagonist, Makina, a young woman who will undergo a series of trials on her quest to deliver a message to her brother; he disappeared years earlier while searching on the other side of the border for a plot of land promised to their family. In order to cross, Makina first has to pass through various criminal underworlds; once on the other side, she finds herself in a place where “signs prohibiting things throng in the streets, leading citizens to see themselves as ever protected, safe, friendly, innocent … salt of the only earth worth knowing.” And full of lunatic vigilantes with shotguns, of course. As in the Tawada, reflections on language hold pride of place; unlike The Emissary, however, which hums with claustrophobic tension, Signs feels vast: Makina’s story is told in a Spanish brimming with neologisms and inflected with a wide range of linguistic and cultural references from across the centuries, a Herculean task of translation to which Lisa Dillman responded with stunning grace and acuity.

Double take: Maya Jaggi teases out the book’s the tightly woven allusions for The Guardian.

These Possible Lives by Fleur Jaeggy

Translated from the Italian by Minna Zallman Proctor

New Directions (July 2017)

And now for something completely different. The tiniest of this month’s tiny books, These Possible Lives, by the reclusive Swiss writer Fleur Jaeggy, is made up of three biographical sketches—or perhaps more accurately, death masks—of Thomas De Quincey, John Keats, and Marcel Schwob. To me, the greatest wonder of this work is how Jaeggy, and then Proctor, managed to wring so much poetry out of such compact sentences (Sheila Heti explores this facet of Jaeggy’s writing in a piece for The New Yorker on Jaeggy’s short story collection I Am the Brother of XX, which is exquisite and could just as easily have been the focus of this write-up). De Quincey’s entry into the world of opium “was like being a guest in the pages of a richly illustrated encyclopedia for children,” while Keats “looks like a girl, and if we think of him as a girl, the femininity of his features evaporates and he seems stubborn and volatile, the constant surveyor of his own visions.” These strange and beautiful portraits cast familiar faces in an unfamiliar light, whittling down their imposing subjects until what is left is a finely-wrought catalog of vanities, superstitions, desires, and fears.

Double take(s): Emily LaBarge digs into the dark recesses of this gem for the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Martin Riker sets it in the context of Jaeggy’s other work for the New York Times.

Self-Portrait in Green by Marie NDiaye

Translated from the French by Jordan Stump

Two Lines Press (November 2014)

Last month, I alluded to my (completely measured and reasonable) obsession with Marie NDiaye, a virtuosic writer who published her first book at the age of 17, followed that up with a 200-page novel written in a single sentence, and then went on to win the prestigious Prix Goncourt in 2009 for her Trois femmes puissantes. Well, this slim, enigmatic volume is where it all started for me. Self-Portrait operates at the place where narrative meets memoir, bringing together fragmentary encounters with the women in green, a melancholy parade of figures living and dead whose strength has been forged in neglect and fed by regret (theirs and others’). In one storyline, a woman named Jenny pays a daily visit to the wife of her ex, who shares with her the minute details of her life with the man Jenny rejected years earlier. When asked why the woman should volunteer this information, the remorseful Jenny responds, “To console me.” In another, the author’s own mother turns into one of the “most alien and troubling forms” of the so-called “green woman,” while in a third, the high-school friend who became NDiaye’s stepmother lives in poverty and frustration under the thumb of the author’s father. These women, disparate yet united in their desperation, are all also—as the title suggests—NDiaye: they both define the contours of her world, and speak to a shared experience. Each time I return to it, I’m left speechless by this powerful meditation on the complex relationships among women.

Double take: Patty Nash for Asymptote on the curious art of the self-portrait.

* As M.A. Orthofer points out in his write-up of the NBA list, an award for translation was given out between 1967 and 1983.

1. Transcription by Kate Atkinson

6 Rave 6 Positive 3 Mixed

“Within a deceptively familiar form, Transcription treats the lives and labor of women with fresh complexity … Atkinson has predicated her enormously successful career upon giving readers intelligent and artful iterations of what they already know they like … In her best work—a category in which her latest, Transcription, certainly belongs—she maneuvers the tropes of the murder-mystery genre, of historical fiction, and of privileged white Britishness into a kind of critical salvage of women’s work, women’s lives, that’s as heterodox, in its way, as Cusk’s … before you know it Transcription has turned from a wartime spy yarn into a fuguelike meditation on the fungibility of female identity…Far from interfering with the plot of Transcription, this meditation on identity kindles it.”

–Jonathan Dee (The New Yorker)

*

2. Your Duck is My Duck by Deborah Eisenberg

8 Rave 2 Positive

“[Eisenberg] is always worth the wait. The new book is cannily constructed, and so instantly absorbing that it feels like an abduction … On the face of it, Your Duck Is My Duck could be regarded as a politically mild book for Eisenberg. The world intrudes only at the margins—tumult is hinted at in unnamed countries, glimpses of unspecified migrants. But these are stories of painful awakenings and refusals of innocence. This book offers no palliatives to its characters or to its readers—no plan of action. But it is a compass.”

–Parul Sehgal (The New York Times Book Review)

Read an interview with Deborah Eisenberg here

*

3. The Shape of the Ruins by Juan Gabriel Vasquez

3 Rave 4 Positive

“…[a] clever, labyrinthine, thoroughly enjoyable historical novel … Ironic one moment, earnest the next, Vásquez presents himself as the central character of his own book. We learn about his career as a novelist, the state of his marriage, the birth of his daughters; we learn to be uncertain about what is fiction and what is not, what’s history and what’s debatable … Even at their most grotesque or bloodstained or slyly comic, these anecdotes and observations retain their humanity. Vásquez assembles them into a discursive, mischievous autofiction, combining forensic medicine with hearsay, revealing a third-hand source behind a first-hand account, setting public memory against private, chatter against documentation, until The Shape of the Ruins is less an album of stickers than a comprehensive critique of conspiracy aesthetics.”

–M John Harrison (The Guardian)

*

4. An Absolutely Remarkable Thing by Hank Green

2 Rave 4 Positive 2 Mixed

“Green is clearly interested in how social media moves the needle on our culture, and he uses April’s fame, choices, and moral quandaries to reflect on the rending of social fabric. Fortunately, this entertaining ride isn’t over yet, as a cliffhanger ending makes clear. A fun, contemporary adventure that cares about who we are as humans, especially when faced with remarkable events.”

–(Kirkus)

5. Waiting for Eden by Elliot Ackerman

2 Rave 4 Positive 1 Mixed

“…[a] gorgeously constructed short novel … Both Eden’s and Mary’s fears and foibles are richly explored to create a deeply moving portrayal of how grief can begin even while our loved ones still cling to life. In this unique Afghanistan and Iraq Wars novel, which joins a growing genre that includes Kevin Powers’ Yellow Birds (2012) and Phil Klay’s Redeployment (2014), Ackerman’s focus on a single family makes the costs of war heartbreakingly clear, as does his drawing emotion and import from the smallest of acts with incredible skill. Many will read this wonderful novel in a single sitting.”

–Alexander Moran (Booklist)

Elliot Ackerman on Five Books That Straddle Life and Death

**

1. Hiking With Nietzsche by John Kaag

2 Rave 6 Positive

“As in American Philosophy, Kaag deftly intertwines sympathetic biography, accessible philosophical analysis, and self-critical autobiography … [Kaag’s] book takes us on a hike through Nietzsche’s manically prolific output, which occasionally feels like a forced march but more often feels like an invigorating excursion. Scrambling up treacherous rocky inclines in worn sneakers, Kaag reflects on the peaks and valleys of Nietzsche’s life and philosophy … Kaag extracts plenty of relevant ideas from Nietzsche and his followers in this stimulating book about combating despair and complacency with searching reflection.”

–Heller McAlpin (NPR)

Read an excerpt from Hiking With Nietzsche here

*

2. Beautiful Country Burn Again by Ben Fountain

3 Rave 3 Positive

“…an openhearted patriotic spirit of fellowship with his countrymen and a mounting sense of distress that Americans have always been but are now especially vulnerable to fraudulent appeals to their ugliest instincts. Most of his excursions on the road and through the past yield a tableau mixing the venal and the humane. But understanding requires an index of national villains … Sketching the history of racial politics since World War II and the GOP’s Southern Strategy, Fountain paints Trump as the second coming of Barry Goldwater … The strongest and most damning section of Beautiful Country Burn Again is the part that’s been most heavily revised in the election’s aftermath: a history of Hillary Clinton’s career … painting her as the tool of ‘a morally bankrupt system that she’d played a large and active role in creating … Nihilism’s a blast for people who’ve been lied to all their lives.’ ”

–Christian Lorentzen (Bookforum)

Read an excerpt from Beautiful Country Burn Again here

*

3. The Order of the Day by Éric Vuillard

3 Rave 2 Positive

“Éric Vuillard’s The Order of the Day covers this moment in Austrian history, and reveals it as more than just an Austrian moment. Buried in this event are all the elements which led to the spread of fascism in Europe: greed, ambition, obsequiousness. The elitism and greed of corporate capitalists, eager to hedge all their bets and finance any rising star, however odious; the servile deference of public figures who preferred to follow the rising (Nazi) political stars rather than confront them in the name of decency, integrity or democracy; the fawning and genteel ignorance of Western governments, who didn’t know how to respond to the brutish idiocy of Hitler and the opportunistic goons he surrounded himself with … It’s short, scathing, and the highly stylized literary narrative achieves near-poetic heights of form. Still, it’s well-researched and defiantly concrete as well.”

–Hans Rollman (Popmatters)

*

4. Rising Out of Hatred by Eli Saslow

1 Rave 6 Positive

“It may be the exception that proves the rule in these partisan times, but the transformational tale of Derek Black is powerful and riveting all the same … Eli Saslow, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist at The Washington Post, has written an eye-opening account of one man’s ideological metamorphosis. Rising out of Hatred: The Awakening of a Former White Nationalist is at once disturbing and uplifting.”

–David Holohan (The Christian Science Monitor)

*

5. The King and the Catholics by Antonia Fraser

1 Rave 4 Positive

“Antonia Fraser’s last history book was about the ‘perilous question’ of parliamentary reform in 1832. The King and the Catholics takes on the ‘abominable question’ of Catholic emancipation three years earlier. It is also, Fraser writes, ‘in one sense, the sequel’ to her seminal study of the gunpowder plot. It deals with religious intolerance, xenophobia, rising populism, ‘a people strangely fond of royalty’ (Lord Holland’s observation), and a seemingly intractable Irish problem. It was the great issue of the day, ‘mixed up with everything’, one bishop noted, that ‘we eat or drink or see or think’ … Fraser, a convert to Catholicism, as well as a descendant of the Anglo-Irish Protestant Longfords, tells the story with erudition, sprezzatura and a tremendous sense of fun. Every page is shot through with humour and humanity.”

–Jessie Childs (The Guardian)

Boy, have we got some intriguing pairings of critic and subject for you this week. Let’s begin with National Book Award-winning titan of disturbing America fiction (and noted Twitter provocateur) Joyce Carol Oates, who, in her New York Review of Books essay on My Year of Rest and Relaxation, calls Ottessa Moshfegh’s sophomore novel “a perverse fusion of Sex and the City and Requiem for a Dream.” Over at the New York Times, Pulitzer Prize-winner and author of the New York-in-wartime novel Manhattan Bach Jennifer Egan had mixed feelings about Kate Atkinson’s Transcription, admiring how Atkinson conjures WWII-era London but disappointed by the novel’s “cipherlike” protagonist. Goshawks met ravens in the Atlantic‘s books section this week as naturalist and H is for Hawk author Helen Macdonald wrote about Christopher Skaife’s “marvelous” memoir The Ravenmaster: My Life With the Ravens at the Tower of London. We also take a closer look at writer and activist Rebecca Solnit’s New Republic piece on the recent literature of female rage, and Moira Weigel’s Guardian takedown of Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind.

*

“Ottessa Moshfegh’s second novel reads like an uncensored, unapologetic, despairingly funny confession … In flat, deadpan, unembellished prose recalling the cadences of Joan Didion and the clear-eyed candor of Mary Gaitskill, Moshfegh portrays the vacuous interior life (she has virtually no exterior life) of a narcissistic personality simultaneously self-loathing and self-displaying … Her drug-taking is a means of escaping from ‘the tragedy of my past’; she cannot express mourning, it seems, perhaps because she had not loved her parents, and so she is trapped in melancholia—a paralysis of the spirit. Yet My Year of Rest and Relaxation is most convincing as an urbane dark comedy, sharp-eyed satire leavened by passages of morbid sobriety, as in a perverse fusion of Sex and the City and Requiem for a Dream … More engaging than Eileen, more varied in tone, and much funnier, My Year of Rest and Relaxation is a recycling of the materials of Eileen that tracks a disagreeable, self-absorbed young woman in her twenties through a cathartic experience that leaves her ostensibly altered and prepared for a new, freer life.”

–Joyce Carol Oates on Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (The New York Review of Books)

*

“I can make a passable imitation of a raven’s low, guttural croak, and whenever I see a wild one flying overhead I have an irresistible urge to call up to it in the hope that it will answer back. Sometimes I do, and sometimes it does; it’s a moment of cross-species communication that never fails to thrill. Ravens are strangely magical birds. Partly that magic is made by us. They have been seen variously as gods, tricksters, protectors, messengers, and harbingers of death for thousands of years. But much of that magic emanates from the living birds themselves. Massive black corvids with ice-pick beaks, dark eyes, and shaggy-feathered necks, they have a distinctive presence and possess a fierce intelligence … There’s joy in The Ravenmaster, as well as tragedy, obsession, and a rare tenderness toward Skaife’s avian charges … Skaife is doing us, I think, a small political service by introducing us to the quirks and histories of every bird in his care; he is letting us love them in a way that makes them more than mere symbols. Ravens have long been regarded as messengers, and the message the birds in this marvelous book have given me is this: Perhaps, by paying much closer and more careful attention to the reality of the things we unconsciously use to claim the past, we might move a little further toward safety in a world that seems to be teetering on the brink.”

–Helen Macdonald on Christopher Skaife’s The Ravenmaster (The Atlantic)

*

“Fans of Life After Life, Atkinson’s 2013 masterpiece, will recognize the artful pathos with which she renders the war’s cratering effect on Londoners. But what interests Atkinson here is less the war’s aftermath than its simmering persistence … watching through Juliet’s irreverent eyes as MI5 recruits upper-class ‘girls’ for possible spy work is fascinating and deliciously comic … Atkinson’s use of comedy in the first half of the novel is unexpected and inspired; even the Dada-esque chunks of Juliet’s transcription are animated by our awareness of her exasperated confusion as she types them … The deeper problem in the last half of Transcription lies with Juliet. Beguiling as an excitable ingénue, she becomes cipherlike as the book progresses. Her actions seem unintelligible at times, her plucky asides almost perversely frivolous in the face of serious events … Atkinson is keeping a secret about Juliet, and its revelation comes as a major surprise toward the end of the novel. Juliet’s opacity may be part of Atkinson’s strategy. Spies, after all, are notoriously hard to read—it’s part of the job description. ‘The mark of a good agent is when you have no idea which side they’re on,’ Juliet is advised by her boss. But a good agent can prove a frustrating protagonist; a spy may require a second spy to make her spill her secrets.”

–Jennifer Egan on Kate Atkinson’s Transcription (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“These books arrive at a moment when a lot of women have changed and too many men have not—and some are, in fact, retreating into revved-up misogyny and rage against the erosion of their supremacy. Women no longer obliged to please men may finally be able to express rage, because we’re less economically dependent on men than ever before, and because feminism has been redefining what’s appropriate and acceptable … Much of what Traister and Chemaly address in their books is a double bind: We live in a world in which there is a good deal for women to object to, including the fact that a lot of men wish to harm and humiliate and subjugate us, but responding to that comes with its own penalties. When a woman shows anger, Chemaly observes, ‘she automatically violates gender norms. She is met with aversion, perceived as more hostile, irritable, less competent, and unlikable.’ But even if, for example, she says quite calmly that gender violence is epidemic, she can still be attacked and characterized as angry, and that anger can be used as a way to discount the evidence, in a society that often still expects that women be pleasing and compliant … Most great activists—from Ida B. Wells to Dolores Huerta to Harvey Milk to Bill McKibben—are motivated by love, first of all. If they are angry, they are angry at what harms the people and phenomena they love, but their urges are primarily protective, not vengeful. Love is essential; anger is perhaps optional.”

–Rebecca Solnit on Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her, Brittney Cooper’s All the Rage, and Rebecca Traistor’s Good and Mad (The New Republic)

*

“The Coddling of the American Mind is less interesting for its anecdotes or arguments, which are familiar, than as an epitome of a contemporary liberal style. That style wants above all to be reasonable. Lukianoff and Haidt include adverb after adverb to telegraph how well they have thought things through … The style that does befit an expert, apparently, is the style of TED talks, thinktanks and fellow Atlantic writers and psychologists. The citations in this book draw a circle around a closed world. In offering a definition of ‘identity politics,’ a term coined by the black socialist lesbians of the Combahee River Collective (and the subject of a recent book edited by Yamahtta-Taylor), Lukianoff and Haidt quote ‘Jonathan Rauch, a scholar at the Brookings Institution.’ They tell their readers to read Pinker, whose fulsome blurb appears on their book jacket … Lukianoff and Haidt go out of their way to reassure us: ‘Neither of us has ever voted for a Republican for Congress or the presidency.’ Like Mark Lilla, Pinker and Francis Fukuyama, who have all condemned identity politics in recent books, they are careful to distinguish themselves from the unwashed masses—those who also hate identity politics and supposedly brought us Donald Trump. In fact, the data shows that it was precisely the better-off people in poor places, perhaps not so unlike these famous professors in the struggling academy, who elected Trump; but never mind. I believe that these pundits, like the white suburban Dad in the horror film Get Out, would have voted for Barack Obama a third time … The core irony of The Coddling of the American Mind is that, by opposing identity politics, its authors try to consolidate an identity that does not have to see itself as such. Enjoying the luxury of living free from discrimination and domination, they therefore insist that the crises moving young people to action are all in their heads. Imagine thinking that racism and sexism were just bad ideas that a good debate could conquer!”

–Moira Weigel on Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind (The Guardian)

Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to DC-based writer, critic, and NBCC member, Martha Anne Toll.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Martha Anne Toll: I’ll choose John A. Williams’ The Man Who Cried I Am and Sanora Babb’s Whose Names Are Unknown.

Some of the most meaningful books in my life come from reading obituaries. Important writers are lost due to racism or sexism, or because more trendy, short-lived books drown them in the sea of popular opinion. After reading an obituary of John A. Williams in 2015, I looked for his masterpiece The Man Who Cried I Am and could only obtain it on a used book site. This epic novel is the story of a Black man who served in the navy in World War II and returns to a virulently racist America where he cannot establish himself as the gifted journalist that he is, nor live the life of his white counterparts who were welcomed back into society. White police are randomly killing Black boys, Williams’ protagonist cannot get a job and believes the government is in a conspiracy to crush Black lives, and loving a white woman poses mortal risk. The book was published in 1967. Williams is of equal caliber to the literary titans of his generation-Norman Mailer, Bernard Malamud, Joseph Heller, Philip Roth, and Saul Bellow-and I was heartbroken that I hadn’t heard of him. Similarly, I found Sanora Babb after her death in 2005. Babb’s searing novel on life in the Dust Bowl during the Depression, Whose Names Are Unknown, was accepted and subsequently turned down by Bennett Cerf at Random House because John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath had just been submitted. Babb, a journalist who covered the Dust Bowl refugees, writes with intimate and empathic knowledge of her subject.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

MAT: I’ll fudge by a year or two and choose The Tongue of Adam by Abdelfattah Kilito, translated from French by Robyn Creswell. I picked this miniature book up at Gulf of Maine Books in Brunswick, Maine and was immediately entranced. Kilito is a Moroccan who grew up in two literary worlds-Arabic and French. A prodigious reader and scholar, Kilito’s cross-cultural experience is a launching pad to ask: What language did Adam speak? And why does it matter? Drawing from the Bible, the Qu’ran, and from scholars around the world, The Tongue of Adam is both accessible and delightful. I look forward to reading more of Kilito’s work.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

MAT: I find the word “critic” to be a misnomer. I don’t read books to criticize them. I read books because they are nourishing and life-sustaining and exponentially expand my world. I write about books to share the pleasures they offer. I review books to excite future readers, to champion writers, and to spread learning and joy. That is not to say that all books are created equal; there are some pretty awful ones out there. I don’t want to waste readers’ time reviewing those. What would be the point? I’m not interested in disparaging any writer because I know that just putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard requires an act of courage. I do, however, try to avoid reviewing books I dislike. On more than one occasion I have bowed out of an assignment where I thought I would have to be too negative.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

MAT: That is a big topic, and I am not qualified to answer! The demise of many well-respected book review outlets is a loss to all of us. I am not sure whether, and if so, how, that demise is connected to social media. On the other hand, social media has greatly widened the field of people commentating on books that they love. I get a lot of reading suggestions from Twitter. Well-Read Black Girl comes to mind, as well as @tedgioia and @TobiasCarroll.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

MAT: There are so many, but I’ll call out James Wood at the New Yorker whose depth and eloquence I greatly admire; Dwight Garner of the New York Times, who has an expansive frame of reference; and Ron Charles of the Washington Post, whose clear, accessible style, and well-reasoned opinions are appealing. I also love reading books about books, and have found wonderful recommendations that way. An essay in Toni Morrison’s What Moves at the Margin about her discovery of Gayl Jones’s Corregidora led me to that book, which was a thrilling discovery.

Here’s a short list of books about books, including writers’ and editors’ memoirs, that have yielded great reading recommendations:

Diana Athill’s Stet: An Editor’s Life

Nicholas A. Basbanes’ Every Book Its Reader

Roberto Calasso’s The Art of the Publisher

Pat Conroy’s My Reading Life

Robert Gottlieb’s Avid Reader: A Life

Pamela Paul’s My Life With Bob

Lynne Sharon Schwartz’s Ruined By Reading

Jeanette Winterson’s Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

James Wood’s The Nearest Thing to Life

*

Martha Anne Toll‘s book reviews and essays appear regularly on NPR’s website, The Millions, Heck, [PANK], The Nervous Breakdown, Tin House blog, Bloom, Narrative, Cargo Literary, and the Washington Independent Review of Books. Her fiction has appeared in Catapult, Vol.1 Brooklyn, Yale’s Letters Journal, Slush Pile Magazine, Poetica E Magazine, Referential Magazine, and Inkapture Magazine. She directs a social justice foundation focused on preventing and ending homelessness and on reforming the criminal justice system. @marthaannetoll

*

The quest to find the country’s most beloved book continued at pace last night with “Heroes,” the second themed episode in PBS’ The Great American Read—a new eight-part series that explores and celebrates the power of reading, told through the prism of America’s 100 favorite novels.

“Heroes” (which featured interviews with Seth Meyers, Shaquille O’Neal, Sarah Jessica Parker, James Patterson, Jason Reynolds, Parul Seghal, Baratunde Thurston, Kevin Young, Venus Williams and others) reintroduced us to a selection of literature’s most iconic embattled protagonists—from Katniss Everdeen to Winston Smith, Yossarian to Ignatius J. Reilly—and examined how these everyday heroes and anti-heroes find their inner strength, overcome challenges, and rise to the occasion.

As we’ll be doing the day after each week’s themed episode from now until the grand finale on October 23, we looked back through our Classic Reviews Archive to show you what the critics said about some of these legendary heroic journeys.

*

Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

Perhaps one did not want to be loved so much as to be understood.

“Nineteen Eighty-Four goes through the reader like an east wind, cracking the skin, opening the sores; hope has died in Mr Orwell’s wintry mind, and only pain is known. I do not think I have ever read a novel more frightening and depressing; and yet, such are the originality, the suspense, the speed of writing and withering indignation that it is impossible to put down. The faults of Orwell as a writer—monotony, nagging, the lonely schoolboy shambling down the one dispiriting track—are transformed now he rises to a large subject.

…

“The duty of the satirist is to go one worse than reality; and it might be objected that Mr Orwell is too literal, that he is too oppressed by what he sees, to exceed it. In one or two incidents where he does exceed, notably in the torture scenes, he is merely melodramatic: he introduces those rather grotesque machines which used to appear in terror stories for boys. But mental terrorism is his real subject.

…

“For Mr Orwell, the most honest writer alive, hypocrisy is too dreadful for laughter: it feeds his despair. Though the indignation of Nineteen Eighty-Four is singeing, the book does suffer from a division of purpose. Is it an account of present hysteria, is it a satire on propaganda, or a world that sees itself entirely in inhuman terms? Is Mr Orwell saying, not that there is no hope, but that there is no hope for man in the political conception of man?”

–V.S. Pritchett, The New Statesman, June 18, 1949

*

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

I mingle with my peers or no one, and since I have no peers, I mingle with no one.

“The problem with writing about a funny book, like a good joke, is that you can’t really describe it, you just have to retell it. And criticism is never so clearly a matter of taste as when it is applied to humor. I don’t like the Three Stooges or Mel Brooks or even, except occasionally, Woody Allen. I am the kind of surly reader who doesn’t laugh out loud at books, even at passages I find genuinely funny. I found myself laughing out loud again and again as I read this farcical, ribald book.

…

“[Ignatius] is the quintessential pessimist who is continually offended by the world ill-equipped to recognize his genius. An obese, mephitic 30-year-old M.A., he lives with his mother and spends most of his time in his room scribbling his orotund philosophy and history of society in Big Chief tablets, coming out only to grab an occasional Dr. Nut from the fridge, watch television, or visit the local movies to complain loudly about the lack of taste and decency being presented on the screen. He is one of the most repelling, entertaining, and, is some strange way, sympathetic characters I have ever encounteredc.

The setting is New Orleans, where Toole renders as surrealistic a social landscape as one would ever hope to find, peopled by characters whose dialects only gain in comic effect by clashing with Ignatius’ educated and bombastic diction.

The first and only novel completed by John Kennedy Toole before his death in 1969, this book is only now being published because Toole’s mother brought a manuscript to Walker Percy, who reluctantly began to read it and soon realized that what he had in hand was ‘a great rumbling farce of Falstaffian dimensions.’

Toole doesn’t use his characters as convenient targets for falling objects of one sort or another. Blacks, WASPS, Homosexuals, policemen, conservatives, radicals, and more are laughable here, but they are more than caricatures or stereotypes. Toole has succeeded in creating characters with comic essenses, whose laughability is somehow a predetermined feature, like an unusually large nose, so that while they proceed through life with something close to the same proportion of problems, successes, logic and absurdity as the rest of us, we can’t help but laugh at what makes them incongruous, or feel sympathetic toward what makes them human.

The title is from Jonathan Swift: ‘When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him.’ There is a sort of genius in Ignatius’ ability to survive, and, in fact, to better his antagonists, and there was an unmistakable comic genius in the creator of this book.”

–Brad Owens, The Christian Science Monitor, June 4, 1980

*

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.

“Catch-22, by Joseph Heller, is not an entirely successful novel. It is not even a good novel. It is not even a good novel by conventional standards. But there can be no doubt that it is the strangest novel yet written about the United States Air Force in World War II. Wildly original, brilliantly comic, brutally gruesome, it is a dazzling performance that will probably outrage nearly as many readers as it delights. In any case, it is one of the most startling first novels of the year and it may make its author famous … Catch-22 is realistic in its powerful accounts of bombing missions with men screaming and dying and planes crashing. But most of Mr. Heller’s story rises above mere realism and soars into the stratosphere of satire, grotesque exaggeration, fantasy, farce and sheer lunacy. Those who are interested may be reminded of the Voltaire who wrote Candide and of the Kafka who wrote The Trial.

“Catch-22 is a funny book—vulgarly, bitterly, savagely funny. Its humor, I think, is essentially masculine. Few women are likely to enjoy it. And perhaps ‘enjoy’ is not quite the right word for anyone’s reaction to Mr Heller’s imaginative inventions. ‘Relish’ might be more accurate. One can relish his delirious dialogue and his ludicrous situations while recognizing that they reflect a basic range and disgust.

Joseph Heller’s key sentence is this: ‘Men went mad and were rewarded with medals.’ His story is a satirical denunciation of war and of mankind that glorifies war and wages war cruelly, stupidly, selfishly. So Mr. Heller satirizes among other matters: militarism, red tape, bureaucracy, nationalism, patriotism, discipline, ambition, loyalty, medicine, psychiatry, money, big business, high finance, sex, religion, mankind and God.

Yossarian was brave once. But he had cracked up and couldn’t face any more bombing missions: ‘He had decided to live forever or die in the attempt, and his only mission each time he went up was to come down alive.’ Unfortunately, the colonel, who wanted to be a general, kept raising the number of compulsory missions. By the time they reached ninety everybody had cracked up and insanity prevailed.

More than a score of Yossarian’s friends and enemies play prominent parts in his story and each gets one or more chapters to himself. Each is a marvel of fear, cupidity, lust, ambition, dishonesty, stupidity or incompetence. The war effort—defeating Hitler, supporting the infantry—meant nothing to anybody. Blatant self-interest was the only motive on the strange Island of Pianosa … Catch-22 will not be forgotten by those who can take it.”

–Orville Prescott, The New York Times, October 23, 1961

*

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

“Why did you do all this for me?” he asked. “I don’t deserve it. I’ve never done anything for you.”

“You have been my friend,” replied Charlotte. “That in itself is a tremendous thing.”

“E. B. White has written a book for children, which is nice for us older ones as it calls for big type. The book has liveliness and felicity, tenderness and unexpectedness, grace and humor and praise of life, and the good backbone of succinctness that only the most highly imaginative stories seem to grow.

Wilbur is of sweet nature—he is a spring pig—affectionate, responsive to moods of the weather and the song of the crickets, has long eyelashes, is hopeful, partially willing to try anything, brave, subject to faints from bashfulness, is loyal to friends, enjoys a good appetite and a soft bed, and is a little likely to be overwhelmed by the sudden chance for complete freedom.

Charlotte A. Cavitica (‘but just call me Charlotte’) is the heroine, a large gray spider ‘about the size of a gumdrop.’ She has eight legs and can wave them in friendly greeting. When her friends wake up in the morning she says ‘Salutations!’—in spite of sometimes having been up all night herself, working. She tells Wilbur right away that she drinks blood, and Wilbur on first acquaintance begs her not to say that.

Another good character is Templeton, the rat. There is the goose, who can’t be surprised by barnyard ways. ‘It’s the old pail-trick, Wilbur. . . . He’s trying to lure you into captivity-ivity. He’s appealing to your stomach.’ The goose always repeats everything. ‘It is my idio-idio-idiosyncrasy.’

What the book is about is friendship on earth, affection and protection, adventure and miracle, life and death, trust and treachery, pleasure and pain, and the passing of time. As a piece of work it is just about perfect, and just about magical in the way it is done. What it all proves—in the words of the minister in the story which he hands down to his congregation after Charlotte writes ‘Some Pig’ in her web—is ‘that human beings must always be on the watch for the coming of wonders.’ Dr. Dorian says in another place, ‘Oh no, I don’t understand it. But for that matter I don’t understand how a spider learned to spin a web in the first place. When the words appeared, everyone said they were a miracle. But nobody pointed out that the web itself is a miracle.’ The author will only say, ‘Charlotte was in a class by herself.’

‘At-at-at, at the risk of repeating myself,’ as the goose says, Charlotte’s Web is an adorable book.”

–Eudora Welty, The New York Times, October 19, 1952

*

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon

All the other children at my school are stupid.

Except I’m not meant to call them stupid, even though this is what they are.

“Mark Haddon’s stark, funny and original first novel, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, is presented as a detective story is presented as a detective story. But it eschews most of the furnishings of high-literary enterprise as well as the conventions of genre, disorienting and reorienting the reader to devastating effect … Christopher tells us all we need to know about his condition without reference to medical terminology—just as well, since the term ‘autism’ encompasses a variety of symptoms and behavioral problems that are still baffling behavioral scientists … Haddon manages to bring us deep inside Christopher’s mind and situates us comfortably within his limited, severely logical point of view, to the extent that we begin to question the common sense and the erratic emotionalism of the normal citizens who surround him, as well as our own intuitions and habits of perception … One of the subtle ironies of the book is that young Christopher is ultimately far more hard-boiled than any gumshoe in previous detective fiction…Christopher’s skewed perspective and fierce logic make him a superb straight man, if not necessarily a stellar detective … The gulf between Christopher and his parents, between Christopher and the rest of us, remains immense and mysterious. And that gulf is ultimately the source of this novel’s haunting impact.

–Jay McInerney, The New York Times Book Review, June 15, 2003

*

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

You don’t forget the face of the person who was your last hope.

“While some young adult novels are content to read the way bad sci-fi movies look, [this] book transcends [its] premise with a terrifyingly well-imagined future and superb characterization.

…

“The archetype of the girl survivalist is familiar—she’s tough and resourceful, but kind and sentimental. We are put on notice that Katniss is something different in Chapter 1, when she describes a lynx who followed her around while she hunted. In many books, that lynx would be Katniss’s best friend. But not this one: ‘I finally had to kill the lynx because he scared off game. I almost regretted it because he wasn’t bad company. But I got a decent price for his pelt.’

…

“The concept of the book isn’t particularly original—a nearly identical premise is explored in Battle Royale, a wondrously gruesome Japanese novel that has been spun off into a popular manga series.

Nor is there anything spectacular about the writing—the words describe the action and little else. But the considerable strength of the novel comes in Collins’s convincingly detailed world-building and her memorably complex and fascinating heroine. In fact, by not calling attention to itself, the text disappears in the way a good font does: nothing stands between Katniss and the reader, between Panem and America.

This makes for an exhilarating narrative and a future we can fear and believe in, but it also allows us to see the similarities between Katniss’s world and ours. American luxury, after all, depends on someone else’s poverty. Most people in Panem live at subsistence levels, working to feed the cavernous hungers of the Capital’s citizens. Collins sometimes fails to exploit the rich allegorical potential here in favor of crisp plotting, but it’s hard to fault a novel for being too engrossing.”

–John Green, The New York Times Book Review, November 7, 2008

*

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

When I discover who I am, I’ll be free.

“…a superb book … I think that I may have underestimated Mr. Ellison’s arnbition and power for the following very good reason, that one is accustomed to expect excellent novels about boys, but a modern novel about men is exceedingly rare. For this enormously complex and difficult American experience of ours very few people are willing to make themselves morally and intellectually responsible. Consequently, maturity is hard to find.

…

“…what a great thing it is when a brilliant individual victory occurs, like Mr. Ellison’s, proving that a truly heroic quality can exist among our contemporaries. People too thoroughly determined and our institutions by their size and force too thoroughly determined can’t approach this quality. That can only be done by those who resist the heavy influences and make their own synthesis out of the vast mass of phenomena, the seething, swarming body of appearances, facts, and details. From this harassment and threatened dissolution by details, a writer tries to rescue what is important. Even when he is most bitter, he makes by his tone a declaration of values and he says, in effect: There is something nevertheless that a man may hope to be. This tone, in the best pages of Invisible Man, those pages, for instance, in which an incestuous Negro farmer tells his tale to a white New England philanthropist, comes through very powerfully; it is tragi-comic, poetic, the tone of the very strongest sort of creative intelligence. In a time of specialized intelligences, modern imaginative writers make the effort to maintain themselves as unspecialists, and their quest is for a true middle-of-consciousness for everyone. What language is it that we can all speak, and what is it that we can all recognize, burn at, weep over, what is the stature we can without exaggeration claim for ourselves; what is the main address of consciousness?

Negro Harlem is at once primitive and sophisticated; it exhibits the extremes of instinct and civilization as few other American communities do. If a writer dwells on the peculiarity of this, he ends with an exotic effect. And Mr. Ellison is not exotic. For him this balance of instinct and culture or civilization is not a Harlem matter; it is the matter, German, French, Russian, American, universal, a matter very little understood. It is thought that Negroes and other minority people, kept under in the great status battle, are in the instinct cellar of dark enjoyment. This imagined enjoyment provokes envious rage and murder; and then it is a large portion of human nature itself which becomes the fugitive murderously pursued. In our society man himself is idolized and publicly worshipped, but the single individual must hide himself underground and try to save his desires, his thoughts, his soul, in invisibility. He must return to himself, learning self-acceptance and rejecting all that threatens to deprive him of his manhood.

This is what I make of Invisble Man. It is not by any means faultless; I don’t think the hero’s experiences in the Communist party are as original in conception as other parts of the book, and his love affair with a white woman is all too brief, but it is an immensely moving novel and it has greatness.

“[Post war American literary critic] John Aldridge writes: There are only two cultural pockets left in America; and they are the Deep South and that area of northeastern United States whose moral capital is Boston, Massachusetts. This is to say that these are the only places where there are any manners. In all other parts of the country people live in a kind of vastly standardized cultural prairie, a sort of infinite Middle West, and that means that they don’t really live and they don’t really do anything.

Most Americans thus are Invisible. Can we wonder at thc cruelty of dictators when even a literary critic, without turning a hair. announces the death of a hundred rnillion people? Let us suppose that the novel is, as they say, played out. Let us only suppose it, for I don’t believe it. But what if it is so? Will such tasks as Mr. Ellison has set himself no more be performed? Nonsense. New means, when new means are necessary, will be found. To find them is easier than to suit the disappointed consciousness and to penetrate the thick walls of boredom within which life lies dying.”

–Saul Bellow, Commentary, June, 1952

*

The Giver by Lois Lowry

The worst part of holding the memories is not the pain. It’s the loneliness of it. Memories need to be shared.

“Lowry creates a chilling, tightly controlled future society where all controversy, pain, and choice have been expunged, each childhood year has its privileges and responsibilities, and family members are selected for compatibility.

As Jonas approaches the ‘Ceremony of Twelve,’ he wonders what his adult ‘Assignment’ will be. Father, a ‘Nurturer,’ cares for ‘newchildren’; Mother works in the ‘Department of Justice’; but Jonas’s admitted talents suggest no particular calling. In the event, he is named ‘Receiver,’ to replace an Elder with a unique function: holding the community’s memories—painful, troubling, or prone to lead (like love) to disorder; the Elder (‘The Giver’) now begins to transfer these memories to Jonas. The process is deeply disturbing; for the first time, Jonas learns about ordinary things like color, the sun, snow, and mountains, as well as love, war, and death: the ceremony known as ‘release’ is revealed to be murder. Horrified, Jonas plots escape to ‘Elsewhere,’ a step he believes will return the memories to all the people, but his timing is upset by a decision to release a newchild he has come to love. Ill-equipped, Jonas sets out with the baby on a desperate journey whose enigmatic conclusion resonates with allegory: Jonas may be a Christ figure, but the contrasts here with Christian symbols are also intriguing.

Wrought with admirable skill—the emptiness and menace underlying this Utopia emerge step by inexorable step: a richly provocative novel.”

–Kirkus Reviews, March 1, 1993

*

The Great America Read TV Schedule

“Who Am I?”

Tuesday, September 18, 8:00-9:00 p.m. ET

Explore the ways that America’s best-loved novels answer the age-old question, “Who Am I?” From life lessons to spiritual journeys, these books help us understand our own identities and find our place in the world.

“Heroes”

Tuesday, September 25, 8:00-9:00 p.m. ET

Follow the trials and tribulations of some of literature’s favorite heroes. From Katniss Everdeen to Don Quixote, examine how the everyday hero and the anti-hero find their inner strength, overcome challenges and rise to the occasion.

“Villains and Monsters”

Tuesday, October 2, 8:00-9:00 p.m. ET

Learn why literature’s most notorious villains began behaving badly. Many weren’t born evil, but became that way when faced with some of the same choices we make every day. See what these villains can teach us about our own dark impulses.

“What We Do For Love”

Tuesday, October 9, 8:00-9:00 p.m. ET

Fall in love with some of literature’s most beautiful romances and explore the many forms of love, from family to passion to the unrequited type. Learn how America’s best-loved novels reflect the things we do for love.

“Other Worlds”

Tuesday, October 16, 8:00-9:00 p.m. ET

Take a magical journey to another world through some of America’s best-loved novels. From Middle Earth to Lilliput, the trials and tribulations of these alternate universes help us to better understand our own world.

“Grand Finale”

Tuesday, October 23, 8:00-9:00 p.m. ET

America’s best-loved novel is revealed.

Elliot Ackerman’s Waiting for Eden is published this month. He shares five books that straddle life and death with Jane Ciabattari.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, Jean-Dominique Bauby

After a massive stroke, Bauby, the former-editor of Elle Magazine in France, suffers from “locked-in” syndrome. All of his faculties are paralyzed, but mentally he is alert to his surroundings. This memoir, which he wrote through a method of blinking out the alphabet, is a meditation of what it means be alive as observed by someone on the brink of death.

Jane Ciabattari: I read this amazing book (and incredible feat of will) not long after my father had a stroke that left him with locked-in syndrome. He spent the last five years of his life unable to communicate but clearly alert. Encouraged by Bauby, I found ways of communicating with my father, which worked especially well when I began to share memories and realized he was following along. The imagination is so powerful. As Bauby puts it, “There is so much to do. You can wander off in space or in time, set out for Tierra del Fuego or for King Midas’s court.” Is there a passage that speaks most to you?

Elliot Ackerman: I can’t think of anything I’ve read that’s quite like this slim book. There are so many powerful passages. I guess I’ll pick this one, “Today it seems to me that my whole life was nothing but a string of those small near misses: a race whose result we know beforehand but in which we fail to bet on the winner.” This passage is about regret, about a bet at a horse race that Bauby failed to place through negligence when the odds were in his favor. We often downplay the role chance plays in our life, both in what we achieve but also in the disasters we avoid—if we avoid them. “Those small near misses,” as Bauby puts it, are often too terrifying to acknowledge.

The English Patient, Michael Ondaatje

Four dissimilar characters are brought together in an Italian villa during the Second World War. The “English patient’s” story is told out of sequence, through his memories, and it is woven together with those around him at the villa who are struggling to reorder their own lives in the wake of war and the attendant loss.

JC: A gorgeous novel, which just won the Golden Man Booker Prize, given on the fiftieth anniversary of the award. The “English patient” falls from the sky in a flaming plane, his charred body nursed by Bedouins, now in the care of Hana, a young nurse, and visiting “that well of memory he kept plunging into during those months before he died.” Can you say what Ondaatje does to mimic the mind drifting back in time, despite the destruction of the body, and how he gives us a sense of that in between place?

EA: The structure of this novel is such an accomplishment. Language, character and plot are the most obvious ways we emotionally engage with a story, but often we think less about the role that structure plays. The English Patient is a love story and we don’t love linearly. Ondaatje’s book is a collage of memories. So much of its force comes from this structure, where each fragment draws its meaning from the next.

The Guardians, Sarah Manguso

It opens with a report in the Riverdale Press of a man jumping to his death in front of a train. It is revealed that this man is Manguso’s friend Harris, who had escaped from a psychiatric ward two years before. Through Harris’s death, Manguso erects a monument to their friendship and his life.

JC: Manguso weaves together her reminiscences about her friend, and factual text.

“Harris met the train with his body, offered it his body.

“The train drove into his body. It drove against his body.

“It sent him from his body.”

These lines seem to examine that place that straddles life and death. Are there other points in the book that seem to do this?

EA: The Guardians is also an exploration of grief, which is a subject I was thinking a great deal about as I worked on Waiting for Eden. Grief is a liminal state. The verb implies movement, as though it is something that we are doing and then will conclude. Manguso has this to say about the many explanations of grief:

“What is grief for? Mechanical explanation: Pain directs my attention to an injury or insult and subsides once the injury or insult is mended or neutralized. The pain of loss subsides if I replace what I lost or adjust permanently to accommodate the loss. Evolutionary explanation: Grief is a byproduct of attachment in social animals. The grief of loss teaches me to prevent potential loss of kin. Religious explanation: God, the engineer of all that happens, knows best. All life is but a gauntlet ere I live again in heaven. Real explanation: Love abides. There is no other solace.”

Her “Real explanation” is very true, or at least my experiences with grief teaches me that it is. At the core of grief is its interrelationship with love. Love leads us to grief. But it also leads us out of grief. Love is the beginning and it is the end.

Embers, Sándor Márai

The novel takes place in the waning days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when a retired general, close to death, receives one of his oldest friends who he hasn’t seen in forty years. The reason for that absence is revealed as they sit down for a last dinner together. The result is a duel of words, evasions, and manipulations, as the betrayal which dissolved their friendship is exhumed.

JC: The general, seeking revenge, invites a former boyhood confidant who disappeared to dinner in his castle. The meeting of these two rivals, now in their seventies, becomes a setpiece for a larger look at the world: “’We look inside ourselves and what do we find? An animosity that time damped down for a while but now is bursting out again. So why should we expect anything else of our fellow men? And you and I, too, old and wise, at the end of our lives, we, too, want revenge. . . . Why should we expect better of the world, when it teems with unconscious desires and their all-too-deliberate consequences, and young men are bayoneting the hands of young men of other nations, and strangers are hacking each other’s backs to ribbons, and all rules and conventions have been voided and instinct rules, and the universe is on fire?” Márai’s sophistication about human behavior makes that complicated duel—dominated by the general’s monologue and inquisition—gripping. To what extent do you think the general’s obsessive brooding over this betrayal by his wife and best friend mirrors the author’s feelings toward the the collapsing alliances in Europe?

EA: Ah, maybe you love this book as much as I do? Embers is certainly a political book. It also fits into our classification of books that straddle life and death because the book is set in the waning days of the Austro Hungarian Empire. Like the best political books, it is also deeply personal, even intimate. Graham Greene’s work also comes to mind in this regard. In tone, this novel and The Quiet American have a great deal in common. They’re both allegorical books, and to your point, yes, the general’s obsessive brooding over the betrayal of his wife does seem to be a metaphor for the collapsing alliances in Europe, but I found Embers to be far more compelling than a droll book about failures in early-twentieth century European alliances.

Memorial, Alice Oswald

To retrieve the emotional force of The Iliad, the poet Alice Oswald erects a memorial to the poem itself, by making a chronological eulogization of each character killed in Homer’s epic.

JC: Oswald’s “oral cemetery” turns The Iliad on its head, distilling out the vivid life and focusing us on the endless string of deaths, as if a compilation of obituaries. Are there particular individuals who stand out for you?

EA: In interviews, Oswald say that Memorial is “a translation of the Iliad’s atmosphere, not its story.” With each poem, she tries to excavate the epic poem’s enargeia or “bright unbearable reality.” One of my favorite pieces in this collection is a eulogy of two farmboys turned warriors, Isos and Antiphos:

They used to be shepherds they were hill people

Working out of reach of the world

Those were the two boys Achilles kidnapped

Among the wolves and buzzards of Mount Ida

They said it was wonderful to be tied in creepers

And taken to the other side by the gypsy

They said he could talk to horses

They said his mother was a seal or mermaid

And he introduced them to Agamemnon

The great king of Mycenae poor fools

Who came home as proud as astronauts

And didn’t want to farm any more

And went riding out to be killed by Agamemnon

That image of the soldiers returning home “proud as astronauts” as has always stuck with me. As has the idea that after seeing the war they “didn’t want to farm any more.” Lots of bright unbearable reality in those two stanzas.

*

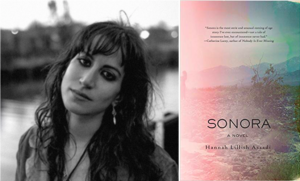

Congratulations to Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Hannah Lillith Assadi, Akwaeke Emezi, Lydia Kiesling, and Moriel Rothman-Zecher, who were announced this morning as the National Book Foundation’s 2018 5 Under 35 honorees!

Each year, five debut fiction writers (under the age of 35) from around the world who have published their first and only book within the last five years, and whose work “promises to leave a lasting impression on the literary landscape,” are selected by previous National Book Award winners, finalists, long listed authors, or writers previously recognized by the 5 Under 35 Program to receive the prestigious award, which also comes with $1000 in prize money.

Previous honorees include Valeria Luiselli, Karen Russell, Justin Torres, Angela Flournoy, Téa Obreht, and Phil Klay, to name but a few.

Curious to know what the critics wrote about these now award-winning authors’ debuts? We’ve got you covered below.

*

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, author of Friday Black

(Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Selector: Colson Whitehead, 2016 National Book Award Winner for Fiction

“Adjei-Brenyah’s dozen stories are disturbingly spectacular, made even more so for what he does with magnifying and exposing the truth. At first read, the collection might register as speculative fiction, but current headlines unmasking racism, injustice, consumerism, and senseless violence prove to be clear inspirations … Ominous and threatening, Adjei-Brenyah’s debut is a resonating wake-up call to redefine and reclaim what remains of our humanity.”

–Terry Hong (Booklist)

*

Hannah Lillith Assadi, author of Sonora

(Soho Press)

Selector: Claire Vaye Watkins, 2012 5 Under 35 honoree

“…[a] wise and poetic debut … Glimpses of the otherworldly abound, alongside an abiding interest in the cosmos, and Assadi’s lyrical prose nicely complements these preoccupations with the unreal or the ungraspable. The structure, moving back and forth in time and space, adds a sense of the magical to a sometimes tragic but always beautiful coming-of-age story.”

*

Akwaeke Emezi, author of Freshwater

(Grove Atlantic Inc.)

Selector: Carmen Maria Machado, 2017 National Book Award Finalist for Fiction

“The novel is based in many of the realities of the writer’s life, but the prose is infused with imaginative lyricism and tone. In the end, this coming-of-age novel also has one foot on the other side, held between the open gates — a young woman of many nations and many souls. The journey undertaken in the novel is swirling and vivid, vicious and painful, and rendered by Emezi in shards as sharp and glittering as those with which Ada cuts her forearms and thighs, in blood offering to Asughara … Emezi’s lyrical writing, her alliterative and symmetrical prose, explores the deep questions of otherness, of a single heart and soul hovering between, the gates open, fighting for peace.”

–Susan Straight (The Los Angeles Times)

*

Lydia Kiesling, author of The Golden State

(MCD Books / Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

Selector: Samantha Hunt, 2006 5 Under 35 honoree

“What Kiesling syntactically accomplishes is an exquisite look at the gulf between the narrow repetitive toil of motherhood and the sprawling intelligence of the mother that makes baby care so maddening … By telling the story of a new mother, someone who might surmount the odds and take a nap but will never achieve a year of rest and relaxation, The Golden State reveals the limitations of the dream of an end to responsibilities. We may all be Bartlebys, preferring not to, but we’re stuck here, caught in the sluggish machinery of late capitalism and its ‘godawful bureaucratic clusterfuck.’ ”

–Heather Abel (Slate)

*

Moriel Rothman-Zecher, author of Sadness Is a White Bird

(Atria Books / Simon & Schuster)

Selector: Bill Clegg, 2015 National Book Award Longlist for Fiction

“Searing in its beauty, devastating in its emotional power, and dazzling in its insights, Moriel Rothman-Zecher’s debut novel, Sadness Is a White Bird, is, I promise you, like nothing you’ve ever read … His particular vision of today’s Israel, told through a coming-of-age story, will break your heart … The novel sings out in the distinctive voices of Rothman-Zecher’s characters, in their almost palpable presence, and in their hopes and hesitations … Rothman-Zecher shows great skill in portraying different neighborhoods, not only in terms of physical characteristics, but also through capturing the cultural and atmospheric dimensions … I have only praise for this poetic, distressingly original book.”

–Philip K. Jason (The Washington Independent Review of Books)

The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past.

Tomorrow, September 25th, marks the 111th birthday of Mississippi’s marquee modernist and the granddaddy of Southern Gothic literature: William Cuthbert Faulkner. One of the most garlanded authors in the history of American letters (with a Nobel, two Pulitzers, and two National Book Awards to his name), Faulkner’s novels and short stories—largely set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, MS—are legendary for their cerebral, stream of consciousness style and grim, often grotesque, happenings. His fictional characters are spiritually impoverished southerners: weary slaves and their embattled descendants, desperate white sharecroppers, morally decayed aristocrats, bitter families with buried secrets.

Below, we look back on a selection of classic reviews of some of Faulkner’s most famous novels—from his notoriously difficult psychological opus, The Sound and the Fury (1929) and the multi-voiced masterpiece, As I Lay Dying (1930), to the WWI-set late-career Christian allegory, A Fable (1954).

*

The Sound and the Fury (1929)

Clocks slay time…time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels;

only when the clock stops does time come to life.

“It is customary to label as experimental books that do not conform to traditional modes of writing, but the traditions have been violated so often of late that this designation no longer fits. The Sound and the Fury, by William Faulkner, is the latest novel that defies classification. To many it will be as incoherent as James Joyce, but its writer is a man of mature talent, and the story, if read with patience, turns such a powerful light on reality that it gains a fast grip on the emotions of the reader.

The books tells the story of a rotting southern family from the viewpoint, for the most part, of an idiot whose present and past are hopelessly jumbled. The distortion in his eyes is so great that as a man of 33 years he is still seeing the events of his boyhood as if they were actually taking place once more. The author, endeavoring to record the psychological reaction of Benjy and the other members of this strange household in terms of their own inability to record logically, tries in a style almost as idiotic as the idiot’s thought process. Hence the reader’s difficulty.

…

“But we cannot dismiss the book merely because some passages are difficult. It has the baffling virtue of making the reader want to understand all the devious ways of these creatures’ minds. On the face of it this is a family not worth artistic attention. And yet the dumb suffering of Benjy; the rich, unselfish devotion of his sister, Caddie, who becomes the plaything of circumstance; the harsh brutality of Jason; the sensitive, self-tortured despair of Quentin, the only one of the family who is educated; and the simplicity of Dilsey, the family servant; together with a view of the broken lives of mother and father, beget an emotional sympathy for these poor players which is proof of the author’s talent.”

–Harry Hansen, The Detroit Free Press, November 17, 1929

*

As I Lay Dying (1930)

My mother is a fish.

“This is a family of groundlings tied to the land, subject to the elements, to the seasons, and to natural disasters. Their lives are unmediated by culture, schooling, or money. It is as if the universe pressing down on them is created by themselves.

Faulkner does a number of things in this novel that all together account for its unusual dimensions. Nothing is explained, scenes are not set, background information is not supplied, characters’ CVs are not given. From the first line, the book is in medias res: ‘Jewel and I come up from the field, following the path in single file.’ Who these people are, and the situation they are dealing with, the reader will work out in the lag: the people in the book will always know more than the reader, who is dependent upon just what they choose to reveal. And at moments of crisis and impending disaster, what is happening is described incompletely by different characters, so as to create in the reader a state of knowing and not knowing at the same time—a fracturing of the experience that has the uncanny effect of affirming its reality.

…

“Apart from its technical achievement, and the descriptive prowess here as in all of Faulkner’s major works, As I Lay Dying can be read as having been written in anticipation of the South’s cultural designation as the symbolic face of the Great Depression. Someone who knew the South, as Faulkner did, would not abide that sort of reductionism. There is no claim of social inequity in this novel; there’s barely a moment or two of compassion. Suffering is not seen as a moral endowment, nor is poverty seen as ennobling.

…

“Faulkner wanted to write a tour de force and he did. His famous claim is that he pulled it off in six weeks. His biographer, Joseph Blotner, says it was more like eight. The book would have been astonishing if it had taken eighty. It is a virtuosic piece, displaying everything that Faulkner has at his disposal, beginning with his flawless ear for the Southern vernacular.”

–E.L. Doctorow, The New York Review of Books, May 24, 2012

*

Light in August (1932)

Dear God, let me be damned a little longer, a little while.

“With this new novel, Mr. Faulkner has taken a tremendous stride forward. To say that Light in August is an astonishing performance is not to use the word lightly. That somewhat crude and altogether brutal power which thrust itself through his previous work is in this book disciplined to a greater effectiveness than one would have believed possible in so short a time. There are still moments when Mr. Faulkner seems to write of what is horrible purely from a desire to shock his readers or else because it holds for him a fascination from which he cannot altogether escape. There are still moments when his furious contempt for the human species seems a little callow.

But no reader who has followed his work can fail to be enormously impressed by the transformation which has been worked upon it. Not only does Faulkner emerge from his book a stylist of striking strength and beauty; he permits some of his people, if not his chief protagonist, to act sometimes out of motives which are human in their decency; indeed, he permits the Rev. Gail Hightower to live his life by them. In a word, Faulkner has admitted justice and compassion to his scheme of things. There was a hint of this to come in the treatment of Benbow in Sanctuary. The gifts which he had to begin with are strengthened—the gifts for vivid narrative and the fresh-minted phrase. His eye for the ignoble in human nature is more keen than ever, but his vision is also less restricted.

There are two or three scenes in this book more searing than anything Faulkner has heretofore written, but they are also better integrated. Although the pattern of Light in August is streaked with red, there is a blending here with colors both more subdued and more luminous than were customary to his palette. The locale is again the ‘deep South’; and the characters include the white trash of which he has drawn such relentless portraits, plain folk of a better strain, whites of a higher order, Negroes, and for the subject of his most detailed attention a poor white with a probable mixture of Negro blood.

Light in August is a powerful novel, a book which secures Mr. Faulkner’s place in the very front rank of American writers of fiction. He definitely has removed the objection made against him that he cannot lift his eyes above the dunghill. There are times when Mr. Faulkner is not unaware of the stars. One hesitates to make conjectures as to the inner lives of those who write about the lives of others, but Mr. Faulkner’s work has seemed to be that of a man who has, at some time, been desperately hurt; a man whom life has at some point badly cheated. There are indications that he has regained his balance.”

–J. Donald Adams, The New York Times, October 9, 1932

*

Absalom, Absalom! (1936)

Tell about the South. What’s it like there. What do they do there. Why do they live there. Why do they live at all.

“The new novel by William Faulkner is worth all the effort required to read it. That is not faint praise. In Fact, it is an almost inevitable primary statement. For Mr. Faulkner again is writing—in Aldous Huxley’s phrase—as though the hounds were after him.

The first few pages of Absalom, Absalom! give the impression of being the start of an escape from Devil’s Island. The reader will have that same sense of plunging into a jungle though which no trails run, of the necessity for labored flight though a malevolent, unknown, fever-stricken land. It is a land of tropical overgrowth. Sentences grow to immense lengths and twist and writhe as though consciously blocking movement. Nightmare emotions rise like djinns from insignificant-seeming causes. Phrases spread out, pushing their wiry lengths down half a page.

…

“Yet there was no simpler way in which he could have told it. Substance cannot be blown up with shadow—until men and women stand huge and important, made massive by a mood—by direct, simple declaration. He has told his story as it should be told to satisfy himself, and while it is entirely conceivable that this book may narrow the audience that was made fairly large by Sanctuary, those who complete the reading of this novel will find that it is an even more remarkable achievement, a better novel, than was Light in August, his finest novel before this.”

–Robert Van Gelder, The New York Times, October 26, 1936

*

A Fable (1954)

War is an episode, a crisis, a fever the purpose of which is to rid the body of fever.

So the purpose of a war is to end the war.

“A modern allegory to which each reader will append his own symbolism, his own interpretation. This is slated for a wide acceptance on intellectual snob appeal, but most honest readers will confess to some difficulty in coming to grips with the essential significance. Conceived as World War II approached its last year, the story envisions World War I—in the trenches in France—coming to an end as the soldiers mutiny. The inspiration of the mass movement is a figure symbolic of the Christ. The action parallels the span of Holy Week—with the triumphant entry, the Last Supper, the Crucifixion, the the resurrection. Judas is there, and Peter, the apostles, Pilate and Herod, the Marys, and so on—recognizable, but distorted-although never with irreverence. Creatively, it is an extraordinary achievement with its underlying commentary on an unready world. Practically, it is difficult reading, and often obscure.”

1. Washington Black by Esi Edugyan

8 Rave • 4 Positive • 1 Mixed

“The beauty here lies in Edugyan’s language, which is precise, vivid, always concerned with wordcraft and captivating for it. Images of slave life are the most powerful of the book, and Big Kit is a formidable creation—a quietly seething figure rather like the strong, suffering women from Marlon James’s The Book of Night Women, and again, one wishes that Edugyan had not decided to abandon her so early on. But the story is broader and more ambitious in its scope … His story becomes increasingly mythic, heading beyond freedom, toward empowerment. It’s not what readers who are wedded to realism might want, but Edugyan’s fiction always stays strong, beautiful and beguiling.”

–Arifa Akbar (The Observer)

*