If you only read one book review this week (why are you starving yourself?), make it James McBride’s stirring New York Times tribute to the peerless Toni Morrison and her latest book, The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations. “Toni Morrison does not belong to black America,” McBride writes, “She doesn’t belong to white America. She is not ‘one of us.’ She is all of us. She is not one nation. She is every nation.”

Over at the Nation, Broken River author J. Robert Lennon considers Tana French’s “extraordinary” standalone thriller, The Witch Elm, in the context of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, writing “the privileged don’t get it, the hearings taught us, because they don’t have to. For most of them, there never is a reckoning. The Witch Elm offers us a brilliant take on this dreary truth…”

Meanwhile, back at the New York Times, Booker Prize-winning Irish author Roddy Doyle commends the storytelling prowess of Patrick Radden Keefe, who vividly evokes the terrible human cost of the Northern Ireland Troubles in his harrowing new nonfiction book, Say Nothing.

We’ve also got Mark O’Connell’s Guardian review of David Wallace-Wells’ chilling climate change prophecy, The Uninhabitable Earth (“The margins of my review copy of the book are scrawled with expressions of terror and despair”), and Kathleen Rooney on Morgan Parker’s latest poetry collection, Magical Negro (“[a] vibrant, angry, and idiosyncratic exploration of politics, black history, black womanhood, hip-hop, popular culture, celebrity, and more”).

*

“Morrison has, as they say in church, lived a life of service. Whatever awards and acclaim she has won, she has earned. She has paid in full. She owes us nothing. Yet even as she moves into the October of life, Morrison, quietly and without ceremony, lays another gem at our feet. The Source of Self-Regard is a book of essays, lectures and meditations, a reminder that the old music is still the best, that in this time of tumult and sadness and continuous war, where tawdry words are blasted about like junk food, and the nation staggers from one crisis to the next, led by a president with all the grace of a Cyclops and a brain the size of a full-grown pea, the mightiness, the stillness, the pure power and beauty of words delivered in thought, reason and discourse, still carry the unstoppable force of a thousand hammer blows, spreading the salve of righteousness that can heal our nation and restore the future our children deserve … Toni Morrison does not belong to black America. She doesn’t belong to white America. She is not ‘one of us.’ She is all of us. She is not one nation. She is every nation.”

-James McBride on Toni Morrison’s The Source of Self-Regard (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“Historically, I’ve tended to prefer crime fiction written in a minimal style, fiction that has Raymond Chandler as its ancestral avatar. This doesn’t represent some overarching personal bias against writerly elaboration; rather, there’s something about the genre that lures its practitioners into unnecessarily discursive explorations of mood and theme…But French is the rare maximalist crime writer who seems unsusceptible to these clichés. Her narrators are loquacious, yet they never bore; she’s a master of setting scene and filling in backstory in a way that makes these contextual necessities feel not workmanlike or utilitarian, but like vital elements of the story in and of themselves … The privileged don’t get it, the [Brett Kavanaugh] hearings taught us, because they don’t have to. For most of them, there never is a reckoning. The Witch Elm offers us a brilliant take on this dreary truth, with the added bonus that justice is actually realized in the end—if only obliquely, unexpectedly, and not through the established channels. Perhaps that makes The Witch Elm less of a crime novel and more of a fantasy. Either way, it’s one of Tana French’s best books, which makes it one of the best of its kind, period.”

–J. Robert Lennon on Tana French’s The Witch Elm (The Nation)

*

“Keefe homes in on McConville and other individuals and, while doing that, tells a good-sized chunk of the history of Northern Ireland, a place George Bernard Shaw called ‘an autonomous political lunatic asylum’ … If it seems as if I’m reviewing a novel, it is because Say Nothing has lots of the qualities of good fiction, to the extent that I’m worried I’ll give too much away, and I’ll also forget that Jean McConville was a real person, as were—are—her children. And her abductors and killers. Keefe is a terrific storyteller. It might seem odd, even offensive, to state it, but he brings his characters to real life … What Keefe captures best, though, is the tragedy, the damage and waste, and the idea of moral injury … Dolours Price and many like her believed that, after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, she had been robbed of any moral justification for the bombings and abductions. The last section of the book, the tricky part of the story, life after violence, after the end, the unfinished business, the disappeared and the refusal of Jean McConville’s children to forget about her—I wondered as I read if Keefe was going to carry it off. He does. He deals very well with the war’s strange ending, the victory that wasn’t.”

–Roddy Doyle on Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“The margins of my review copy of the book are scrawled with expressions of terror and despair, declining in articulacy as the pages proceed, until it’s all just cartoon sad faces and swear words … There is a widespread inclination to think of climate change as a form of compound payback for two centuries of industrial capitalism. But among Wallace-Wells’s most bracing revelations is how recent the bulk of the destruction has been, how sickeningly fast its results. Most of the real damage, in fact, has taken place in the time since the reality of climate change became known … For a relatively short book, The Uninhabitable Earth covers a great deal of cursed ground—drought, floods, wildfires, economic crises, political instability, the collapse of the myth of progress—and reading it can feel like taking a hop-on hop-off tour of the future’s sprawling hellscape … You could call it alarmist, and you would not be wrong. But to read The Uninhabitable Earth—or to consider in any serious way the scale of the crisis we face—is to understand the collapse of the distinction between alarmism and plain realism. To fail to be alarmed is to fail to think about the problem, and to fail to think about the problem is to relinquish all hope of its solution.”

–Mark O’Connell on David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth (The Guardian)

*

“Parker knows how to make the contents of each of her projects deliver on the promise of the words on their covers. In this case, ‘magical’ is a term that is elevating but also objectifying, even dehumanizing, and the archaism of ‘Negro’ gives the reader pause. The vexatious flatness and near-comedy of such a taxonomic title serves as the perfect frame for Parker’s vibrant, angry, and idiosyncratic exploration of politics, black history, black womanhood, hip-hop, popular culture, celebrity, and more … the book operates in part as a quasi-ethnography, taking that tack of a scientific description of the customs of individual people and cultures and filtering it through the sensibility of a poet at the height of her powers of description and perception … The Magical Negro elides and erases rather than illuminates, and this lack of transparency seems vital to Parker’s aim with this book … Rarely has seeing superficiality and ignorance skewered in poetry been so absorbing … This agility—exhibited in virtually every poem—serves to create a book that delights and astonishes even as it interrogates.”

–Kathleen Rooney on Morgan Parker’s Magical Negro (The Los Angeles Review of Books)

There are few things the literary community relishes more than the appearance of a polarizing high-profile book. Sure, any author about to release their baby into the wild will be hoping for unqualified praise from all corners, but what the lovers of literary criticism and book twitter aficionados amongst us are generally more interested in is seeing a title (intelligently) savaged and exalted in equal measure. It’s just more fun, dammit, and, ahem, furthermore, it tends to generate a more wide-ranging and interesting discussion around the title in question. With that in mind, welcome to a new series we’re calling Point/Counterpoint, in which we pit two wildly different reviews of the same book—one positive, one negative—against one another and let you decide which makes the stronger case.

The first installment in Booker Prize-winner Marlon James’ Dark Star fantasy trilogy follows a mercurial mercenary named Tracker who is tasked with finding a missing child. Described as an “African Game of Thrones,” Black Leopard, Red Wolf has generated a lot of buzz over the past few weeks, and will soon be adapted into a movie by none other than Erik Killmonger himself, Michael B. Jordan(!). Overall, the novel has been met with overwhelmingly positive, even rapturous reviews, with just a few nay-sayers.

Today, as is our wont, we’ll be taking a look at a scathing review from one of those nay-sayers, Sukhdev Sandhu of the Guardian, who hated the book, and wrote that “sometimes it evokes Beavis and Butt-Head.” In stark contrast, we’ve also got a rave review from former New York Times literary critic (and book reviewer royalty) Michiko Kakutani for you to chew on. Kakutani calls Black Leopard, Red Wolf “the literary equivalent of a Marvel Comics universe…fused into something new and startling by his gifts for language.”

*

The child is dead. There is nothing left to know.

“In a novel so dizzyingly populated, where geographies multiply and stack up, where the boundaries between the real, surreal and flat-out fantastic seem increasingly fluid, Tracker has to be a point of anchorage, someone to rely on and to care about. Like the emotionally scarred detectives in Scandinavian crime fiction, he’s often gruff and elusive … The next 600 pages amount to one big killing field, in which characters are slashed, garroted, mutilated and raped with abandon. It’s Heart of Darkness for video gamers, a colonial-era catalogue of clichés about Africa—a continent where life is cheap, the women sexual commodities, the inhabitants duplicitous, all values negotiable … The language is meant to shock, but strangely, given that James is often heralded as a Tarantino-like genius at choreographing bones, thugs and disharmony, everything feels plywood-brittle … A small volume could be compiled from the novel’s cringeworthy prose and dialogue. Sometimes it evokes Beavis and Butt-Head … it reads as if James has never set foot in an African forest … If James could go easier on the bloodletting and muscle-bound prose, choose subtlety and sensuousness over teenage-testosterone swagger, there’s still time for him to queer rather than pastiche the franchise fare he’s avariciously eyeing.”

–Sukhdev Sandhu (The Guardian)

“In these pages, James conjures the literary equivalent of a Marvel Comics universe—filled with dizzying, magpie references to old movies and recent TV, ancient myths and classic comic books, and fused into something new and startling by his gifts for language and sheer inventiveness … The fictional Africa in Black Leopard, Red Wolf feels like a place mapped by Gabriel García Márquez and Hieronymus Bosch with an assist from Salvador Dalí … There are allusions in Black Leopard, Red Wolf not just to countless Marvel series and characters (like the Black Panther, Deadpool and Wolverine), but also to myriad literary works including Octavia E. Butler’s sci-fi classic Wild Seed, Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, Tolkien’s Middle-earth novels, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea books … James is such a nimble and fluent writer that such references never threaten to devolve into pretentious postmodern exercises. Even when he is nestling one tale within another like Russian dolls that underscore the provisional nature of storytelling (and the Rashomon-like ways in which we remember), he is giving us a gripping, action-packed narrative … James has created two compelling and iconic characters—characters who will take their place in the pantheon of memorable and fantastical superheroes.”

–Michiko Kakutani (The New York Times Book Review)

Last night at a packed ceremony at NYU’s Skirball Center in New York City, PEN America announced the winners of its 2019 literary awards.

The evening began with acclaimed Mexican-American writer and author of The House on Mango Street Sandra Cisneros receiving the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature. Later on Jackie “Mac” MacMullan was given the ESPN Lifetime Achievement Award for Literary Sportswriting; twelve young writers were recognized with the PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers; Katherine Seligman won the 2019 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction; the PEN/Laura Pels International Foundation Award for Drama was awarded to Larissa FastHorse; the inaugural PEN/Mike Nichols Writing for Performance Award was given to Kenneth Lonergan; Jonah Mixon-Webster was presented with the PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award for Poetry; Apogee Executive Editor Alexandra Watson received the 2019 PEN/Nora Magid Award for Editing; and the PEN/Phyllis Naylor Working Writer Fellowship was awarded to Noni Carter.

Below you’ll find the winners of the 10 main book categories, as well as an illuminating review of each title.

Congratulations to all the winners and nominees!

***

PEN/Jean Stein Book Award ($75,000)

Friday Black, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

(Mariner Books)

“In Friday Black, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah has written a powerful and important and strange and beautiful collection of stories meant to be read right now … Friday Black is an unbelievable debut, one that announces a new and necessary American voice. This is a dystopian story collection as full of violence as it is of heart. To achieve such an honest pairing of gore with tenderness is no small feat … In Friday Black, the dystopian future Adjei-Brenyah depicts—like all great dystopian fiction—is bleakly futuristic only on its surface. At its center, each story—sharp as a knife—points to right now.”

–Tommy Orange (The New York Times Book Review)

*

PEN Open Book Award ($5,000)

Heads of the Colored People, Nafissa Thompson-Spires

(Atria)

“Clever, cruel, hilarious, heartbreaking, and at times simply ingenious, Thompson-Spires’s experimental collection poses a simple, yet obviously not-simple, question: what does it mean to be a black American in this day and age? … Thompson-Spires’s metafictional satires, oriented around questions of blackness, join a particular tradition of African-American fiction, recalling the sardonic absurdism of Everett’s Erasure and Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, among others … Not all of Thompson-Spires’s stories are overtly satirical, and they become progressively more serious as the collection progresses, but a thread of outrageous, glaring self-awareness runs through the collection, granting even many of the more severe tales a tone of dark comedy … Thompson-Spires, thankfully, depicts a wide range of people, not seeking either overwhelmingly positive or negative images of a race but capturing diversity—reality—in much of its multifarious beauty and terror … The real heads, of course, as this brilliant collection of word paintings displays, can be on anybody’s bodies.”

–Gabrielle Bellot (The Los Angeles Review of Books)

*

PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sportswriting ($5,000)

The Circuit: A Tennis Odyssey, Rowan Ricardo Phillips

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

“Unlike John McPhee’s Levels of the Game or, more recently, L. Jon Wertheim’s Strokes of Genius, both of which chronicle individual matches to plumb the depths of professional tennis, Phillips takes a broader perspective to explore a pivotal year in men’s tennis … Phillips reveals his love of tennis on every page. There is a generosity of spirit toward the reader as he explains the tournament calendar, how the A.T.P. ranking system works and how important seedings are in Grand Slam draws. He even includes a comprehensive glossary of tennis terms … [Phillips’] description of the contrasting styles of Federer and Nadal is incisive, lucid and inspired … [Phillips’] prose becomes lyrical as he transmits the shot-by-shot drama of the match. It’s what makes The Circuit such a joy to read: a poet’s love song to the game of tennis.”

–Geoff Macdonald (The New York Times Book Review)

*

PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Short Story Collection ($25,000)

Bring Out the Dog, Will Mackin

(Random House)

“Will Mackin’s Bring Out the Dog is one such collection that cuts through all the shiny and hyped-up rhetoric of wartime, and aggressively and masterfully draws a picture of the brutal, frightening, and even boring moments of deployment … The Things They Carried, Redeployment, and now Bring Out the Dog; war stories for your bookshelf that will last a very long time, and serve as reminders of what America was, is, and can still become.”

–Sara Cutaia (The Chicago Review of Books)

*

PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay ($10,000)

Against Memoir, Michelle Tea

(Feminist Press)

“…the best essay collection I’ve read in years … Tea’s reporting from Camp Trans is the opposite of the broad and ignorant way that gender nonconformity is written about in mainstream news outlets. It is done from a position of deep understanding, of detail … Tea honors the HAGS gang because it’s personal, because it’s important, and because the bad, hard, beautiful life of poor queers doesn’t make it into history. Her writing about butch-femme romance extends one hand back to the history of punk lesbian publishing and another forward, into the future. She writes the lives of the SM dykes, the trans women excluded by normative lesbians, the poor butches who are for some reason never, ever on television. Swagger is a way of walking away from, or through, the tough conditions of a heteronormative world. If Tea over-romanticizes that walk for a moment, it’s a small price for so much truth.”

–Josephine Livingstone (The New Republic)

*

PEN/Bograd Weld Prize for Biography ($5,000)

Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry, Imani Perry

(Beacon Press)

“…Perry mines Hansberry’s life, her indefatigable radicalism, and her queerness, and she prods us to consider what this fuller portrait of a categorically transgressive figure reveals about the state of social justice today … While Hansberry’s family lived comfortably…she quickly learned, as a child, that her relative prominence was no armor against a racist world … Jim Crow threatened all black Americans, class or any other scraping of privilege be damned, profoundly shaped Hansberry’s broad black consciousness. Years later, at a rally in 1963, she declared that ‘between the Negro intelligentsia, the Negro middle class, and the Negro this-and-that—we are one people. … As far as we are concerned, we are represented by the Negroes in the streets of Birmingham!’ … In fitting herself into Hansberry’s story with autobiographical elements, Perry offers a bracing air of familiarity and urgency around the artist, whose legacy has faded since her death from cancer in 1965. By crisscrossing then and now, Perry insists how important it is that our connection to this history—to Hansberry—survive.”

–Brandon Tensley (Slate)

*

PEN/E.O. Wilson Prize for Literary Science Writing ($10,000)

Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, Ben Goldfarb

(Chelsea Green)

“His entirely captivating new book…is surely the most passionate, most detailed, and most readable love-note these dour furry little workaholics will ever get … He relates the intricacies of their natural history with enormous, happy energy—this is the ultimate start-here book for anybody interested in beavers—and he makes the strongest case yet for the extensive benefits beavers provide for their wider surroundings, far more extensive benefits than are typically attributed to these anti-social little brutes. And through it all, Goldfarb maintains a level of fandom that’s downright charming. Eager is a fascinating snapshot of the beaver’s current conservational moment, and it’s a thought-provoking exploration of the benefits beavers bring to the land.”

–Steve Donoghue (The Christian Science Monitor)

*

PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction ($10,000)

In a Day’s Work, Bernice Yeung

(The New Press)

“Bernice Yeung relates [these] stories…with candor and compassion … She balances them with comprehensive research on labor law, rape and sexual assault legislation, and the additional burdens borne by undocumented women workers … Yeung’s book provides crucial information and insight about this ‘long-held open secret,’ making it a must-read for union organizers, advocates, policy makers and legislators—and all of us.”

–Elaine Elison (The San Francisco Chronicle)

*

PEN Translation Prize ($3,000)

Love, Hanne Ørstavik

(Archipelago Books)

“Love, a trim and electrifying novel … is undergirded by the present tense and made incandescent by Orstavik’s seemingly effortless omniscient perspective, sometimes switching between Jon’s mind and Vibeke’s from sentence to sentence … Orstavik’s mastery of perspective and clean, crackling sentences prevent sentimentality or sensationalism from trailing this story of a woman and her accidentally untended child … The primeval darkness of the forest looms, biting as the cold that seems a character throughout this excellent novel of near misses.”

–Claire Vaye Watkins (The New York Times Book Review)

*

PEN Award for Poetry in Translation ($3,000)

A Certain Plume, Henri Michaux

Translated from the French by Richard Sieburth

(NYRB)

“…with Richard Sieburth’s excellent contemporary and colloquial translation of the entirety of the 1930 publication, with facing-page French, we finally have an opportunity to read all thirty-four texts of this 20th-century classic in their original order and setting—and indeed, to read quite a few that were previously untranslated … Certain Plume is the fourth full-length work by Michaux that Sieburth has rendered into English; his experience with the author and long academic and translating career has made his afterword particularly worth attending to. It eruditely situates the book in its literary surround, provides close readings of some pieces, and sketches the biographical backstory that accounts, in part, for the collection’s abundance of death and mayhem.”

–M. Kasper (Rain Taxi)

Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to Massachusetts-based critic and essayist, Becca Rothfeld.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Becca Rothfeld: I’m not sure I would’ve wanted to be a Jewish woman in Europe in the 1920s—so maybe this speaks more to what I would like to review now, from the safety of 21st century Boston—but I would love to have a chance to write about Italo Svevo’s neurotic masterpiece, Zeno’s Conscience, first published in 1924. It’s the pinnacle of what might be my favorite genre: long, nervous, fin-de-siecle novels with crazy, hypochondriac protagonists. Zeno, the narrator of Zeno’s Conscience, does an especially delicious job of fearing yet fetishizing illness. (As do the tubercular denizens of The Magic Mountain, which came out just one year later. In an ideal world someone would let me write an essay about illness in both books, but alas, I don’t think new translations of either are on the immediate horizon.)

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

BR: Taeko Kono’s Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories, originally published in Japan in 1961 and out in a lovely new translation from New Directions this past fall, has been criminally neglected! She’s dazzlingly dark and, to my mind, every bit as good as her better-known compatriots and sometime-contemporaries, Yukio Mishima and Yasunari Kawabata. Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories is full of women with weird, insistent appetites. It’s a joy to see women who want things so ferociously depicted so forcefully in fiction. More generally, it astonishes me and annoys me all the time that people are not fawning over Javier Marias: he’s so great.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

BR: I don’t know that enough people have any conceptions about book critics and criticism to have misconceptions about either. I suppose, to some extent, I often encounter and often resent the utilitarian notion that the “point” of book review is just to generate a recommendation: buy or don’t buy, read or don’t read. The best book reviews are works of literature in their own right and deserve to be read and treasured as such. Think of John Updike’s or Cynthia Ozick’s criticism: the point is not the verdict but the sprawling pleasure of the sentences.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

BR: I try to avoid luddite-adjacent pessimism about the effects of the internet on books and book-reviewing because, at this point, it’s boring. Once glance at Twitter suffices to demonstrate that the internet makes us stupid, dogmatic, churlish, and uncharitable. Economically speaking, the internet is terrible for critics: so many great magazines no longer exist, and the ones that do can’t pay us very much. And socially speaking, I think there are a great number of pressures to conform to an increasingly uniform public-cum-professional opinion, which is disseminated and to some extent enforced via social media. And surely the way we write and “talk” online is also, in ways yet to be fully appreciated, infiltrating and altering the literature we produce, which in turn affects (probably not positively) the books we have to write about.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

BR: Andrea Long Chu and Tobi Haslett are both gorgeous writers. Probably my favorite of all is Amia Srinivasan, who combines such unbelievable brilliance with such unbelievable eloquence. Plus, it always makes me happy to see an analytic philosopher with a robust aesthetic sensibility—they’re such an endangered species.

*

Becca Rothfeld is a PhD candidate in philosophy at Harvard, where she thinks about ethics, aesthetics, and the relationship between them (among other things). She writes book reviews, essays, and the occasional art review for The Nation, The TLS, Bookforum, Art in America, The Hedgehog Review, The New Republic, and elsewhere. She is a two-time finalist for the Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing.

*

Frederic Tuten’s memoir My Young Life publishes next week. He shares five extraordinary memoirs.

Reprieve by John Resko

This is the story of John Resko’s twenty years in Dannemora, one of the worst prisons in America, known as the Alcatraz of the North. At the height of the Great Depression, Resko was married at seventeen and had a child. He had no food or money, so he shot a man in a grocery store hold-up. He was caught and sentenced to death. His third and final reprieve didn’t come until forty minutes before his scheduled execution by electric chair. He became an artist in prison and was eventually released to pursue his life and career.

Resko was my artistic and literary mentor and a much-needed father figure during my teenage years in the Bronx. He plays a significant role in my memoir My Young Life.

Jane Ciabattari: What lessons did you learn from Resko when it came to writing your own memoir?

Frederic Tuten: I met John Resko in 1952, when I was about sixteen and had just dropped out of Columbus High School in the Bronx. I had wanted to be an artist—a painter. An older woman in my building, another of my mentors, fearing that I was too isolated and, in fact, perhaps going off the tracks and on my way to becoming a juvenile delinquent, introduced me to Resko. She thought that he, who had both been in prison for twenty years and was a painter, might guide and help me. He did, and my memoir details how.

Reprieve came out in 1956 and it hit me in a few ways. I had not known anyone who had written a book—no one in my family had even finished high school—and John’s very act of writing the book was a powerful beacon to me. He wrote every morning and shut the world off until he felt he was done for the day. As for the writing itself, it was strong and unsentimental and went to the truth of his life in prison. The memoir told me—as had his life—that in the worst conditions anyone can make his or her way. But to do that you needed will and patience and belief and the ability to endure: how else could John not only survive the hourly brutality of prison life, but flower in it, teaching himself to write and to paint well enough that eventually he attracted the outside attention of important people. These people were so drawn to his work that they spent years trying to get him paroled. Could I not, then, even on a humbler scale, by my own hard work, one day leave the Bronx and the poverty and smallness of the life I was expected to live?

An aspect of John’s memoir has stayed with me, and gave me the hope that I could follow in his footsteps. It was Resko’s wish for the mot juste, his insistence that every word be exact and not its second cousin. And that that perfect word was perfectly placed. I once asked John why, in describing the exterior of Dannemora prison, he said, “architectonically speaking” and not “architecturally speaking.” I didn’t understand the difference and perhaps I still don’t. But what impressed me was his diligence and his wish for exactitude. I’m amazed that I remember his using that phrase after all these 65 years.

Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict by Peggy Guggenheim

Before reading this memoir, I always thought of Peggy Guggenheim as a kind of stodgy person whose celebrity came from being rich and from patronizing famous artists, by building a museum in Venice. I always pictured her as an older, imperious woman, as she seemed in that famous photograph of her in Venice, flanked by two tiny dogs. That is to say, I always imagined her as someone who had never experienced life but only dabbled in it. When you’re young, you never can imagine that an older person has had such an intense romantic life, for instance. In fact, she was an astonishing and fascinating woman, as this memoir shows. I was also extremely smitten by her bursts of wisdom.

JC: To this day I think of visits to her museum in Venice, and the choices she made when selecting the work for her collection. What were the biggest surprises for you as you read her stories about her life?

FT: There are plenty of people who have lots of money and spend it foolishly or selfishly without any purpose except amassing more riches. What made me adore Peggy Guggenheim was that she used her wealth to live to the hilt and that in the process did a great deal of good, if you believe that art has a place in the good. I love her dedication to pleasure. Before reading this memoir, I had no idea of her love affairs, her marriages, her flirtations. She lived among artists whose work she loved and who, in several cases, she supported and brought to light. That apart, she had a kind of sense of reality that I admired.

For example, among her ridiculous marriages—mostly to men who wanted her money—was one husband who spent her fortune lavishly, but who caviled with the billing account of her live-in chef while they were living in the south of France. Her husband claimed the chef had been cheating them, pretending to buy more than what was needed for their meals and getting money for the difference. Peggy’s husband wanted her to fire the chef for it. Mind you, this was during the time of year when much of the touristical south of France was shut down for off-season. Peggy was not pleased with the few restaurants that had remained open, so she imported one of the most famous chefs in Paris to live in her villa and cook. She told her husband she had no wish to fire the chef because the amount he was allegedly stealing from them was of little importance compared to the need for his services.

Of course, I admire her wisdom here. As much as her wisdom for collecting art and making a beautiful little museum in Venice that the world could visit. I must not forget that she paid the rent for a writer I greatly admire, Djuna Barnes. Although, she complained that Barnes had never thanked her.

Living my Life: Volumes 1 & 2 by Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman inspired me through the strength of her anarchist convictions and by the strength of her commitment to social change, a commitment that came at a great cost to her. Her books are windows into a radical time in America that is sadly forgotten. She is relevant as an example of what integrity and spirit means in the darkest political and social climate. During my own radical youth, her life was a testament to living what one believes.

JC: What most impressed you about the ways in which Goldman acted upon her political beliefs?

FT: First of all, her beliefs were radical even in a time when radicalism was current. She was in the avant-garde of everything that even matters today: worker’s rights; birth control; sexual freedom for women, which meant freedom to have sex without having to be constrained by marriage; sexual acceptance of gay men and lesbians who faced prejudice and persecution; freedom of speech; freedom of press. And she lived her beliefs and took the consequences of them. When she spoke against the draft during the First World War, she was convicted under some statute and spent two years in prison. She thought the act of saying what she had said, in speaking out against the draft, was worth the two years in prison.

But I’m extremely impressed that when she was in the Soviet Union, she saw very quickly the political repressions of everyone outside the Bolshevik sphere. She spoke against the suppression of workers’ rights and of anarchist and other non-Bolshevik radicals. Most especially, she was against the power of the state itself, whether it was capitalist or communist, or whatever name it called itself. She was brave enough to share her feelings about the revolution with Lenin and it was clear in his response that she’d better quit town soon, and she did. She is my hero.

Here’s a funny item: Peggy Guggenheim gave the anarchist Emma Goldman $4,000 and a place to live so that Goldman could write her autobiography.

A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway was my idol as a youth. I loved his short stories especially. I was also enamored with what seemed to be his rich, exciting life. I loved his memoir not only for his portraits of writers like Gertrude Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald, but also for the glamor he enrobed Paris with. The memoir’s prose is as seductive as his portrait of the city. Hemingway fed my youthful fantasy of what it meant to be an artist and what it was to be a writer in Paris.

JC: My darling Mark, who you know, and I read this to each other aloud, chapter by chapter, as we were falling in love as undergrads at Stanford (well, we were engaged after knowing each other two weeks, so we read pretty fast!) When we read of Hemingway living in a circle that included Braque and Picasso, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, writers and artists transforming culture, it became a model as we began our life together, long before we first visited Paris. How did A Moveable Feast influence your life?

FT: As mentioned, I had already been powerfully influenced by Hemingway before A Moveable Feast, as many in my generation were. I used to joke that no one could write a grocery list without being influenced by Hemingway’s prose. But it was not just the prose, it was the glamour of his life, for me. As a Bronx boy, the idea of his having lived in Paris and traveled widely had great allure. I myself, at the age of 15, had been galvanized by the thought of Paris and what I imagined to be the artistic and literary scene there. So Hemingway’s myth had already sunk in. But then, A Moveable Feast besotted me completely. I imagined Paris as still being the way he had described it, and I dreamed of being in the very streets and cafés and brasseries he had wrote about in the book. It took a while for me to finally go to Paris and eventually live there. The very first time I was there, I asked a friend to take me to La Closerie des Lilas because I wanted to see the place that Hemingway lovingly described in The Sun Also Rises

After that, everything in Paris seemed the way Hemingway had described it. Every street, every café seemed the way he described it in the memoir.

Even though Paris has so radically changed since the years Hemingway and I had been there, for me, Paris is still his Paris. It is a place that appears in my novels as if it were my home, my true home.

The Price of Illusion by Joan Juliet Buck

I had wanted to read this book because I’d known Joan slightly over the years and had been to her fabulous dinner parties in New York before she left to become the editor of Paris Vogue. What started for me as a mild curiosity ended as a complete admiration for Joan’s daring and passionate life. She writes about some of the more fabulous characters of our time: Peter O’Toole, Tom Wolfe, and her own extraordinary father and mother. It’s a compelling, extraordinary book.

JC: I’m thinking of the section where Joan is eleven and she and her parents move to Ireland to stay with her godfather, John Houston, and she becomes friends with Anjelica, and later, when she was running Paris Vogue, featuring Madame Claude, who invented the term “call girl.” There are so many extraordinary moments, told with such clarity, and matter-of-factness. How do you think she achieves this effect? And what did it show you about telling your own story?

FT: Joan’s book came out just as my own had been accepted for publication. So, in short, I had not read it before working on my own memoir. My relationship to it is not a matter of influence but a matter of affinity. I, myself, had filtered in and out of the Conde Nast and Vogue world when I was writing film reviews in the 60’s. Many of those experiences paralleled with Joan’s, although at different times. It was wonderful for me to see her perspective on the very celebrities I had brushed shoulders with or who were my friends, like Alexander Liberman, for example, the Editorial Director of Vogue.

Joan’s world was filled with glamour and elegance, both sartorial and personal. But most of all, I felt touched by Joan’s childhood and by her parents, who were models of perfection and illusion. Their rise and fall is of tragic proportion. That is to say, from luxury and indulgence and grand villas to the south of France to penury and claustrophobic apartments somewhere in Los Angeles. I love this book.

*

James Baldwin got a shout-out at the Oscars last night!

Yes, upon accepting her Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress—for Barry Jenkins’ adaptation of Baldwin’s 1974 novel, If Beale Street Could Talk—Regina King called the beloved author “one of the greatest artists of our time.” We heartily agree with Regina, and are grateful to her for reminding us to revisit this classic New York Times review (written by none other than Joyce Carol Oates) of Baldwin’s powerful, Harlem-set love story.

*

If Beale Street Could Talk (1974)

Neither love nor terror makes one blind: indifference makes one blind.

“James Baldwin’s career has not been an even one, and his life as a writer cannot have been, so far, very placid. He has been both praised and, in recent years, denounced for the wrong reasons. The black writer, if he is not being patronized simply for being black, is in danger of being attacked for not being black enough. Or he is forced to represent a mass of people, his unique vision assumed to be symbolic of a collective vision. In some circles he cannot lose—his work will be praised without being read, which must be the worst possible fate for a serious writer. And, of course, there are circles, perhaps those nearest home, in which he cannot ever win—for there will be people who resent the mere fact of his speaking of them, whether he intends to speak for them or not.

If Beale Street Could Talk is Baldwin’s 13th book and it might have been written, if not revised for publication, in the 1950’s. Its suffering, bewildered people, trapped in what is referred to as the ‘garbage dump’ of New York City—blacks constantly at the mercy of whites—have not even the psychological benefit of the Black Power and other radical movements to sustain them. Though their story should seem dated, it does not. And the peculiar fact of their being so politically helpless seems to have strengthened, in Baldwin’s imagination at least, the deep, powerful bonds of emotion between them. If Beale Street Could Talk is a quite moving and very traditional celebration of love. It affirms not only love between a man and a woman, but love of a type that is dealt with only rarely in contemporary fiction—that between members of a family, which may involve extremes of sacrifice.

A sparse, slender narrative, told first-person by a 19-year-old named Tish, If Beale Street Could Talk manages to be many things at the same time. It is economically, almost poetically constructed, and may certainly be read as a kind of allegory, which refuses conventional outbursts of violence, preferring to stress the provisional, tentative nature of our lives. A 22-year-old black man, a sculptor, is arrested and booked for a crime—rape of a Puerto Rican woman—which he did not commit. The only black man in a police line-up, he is ‘identified’ by the distraught, confused woman, whose testimony is partly shaped by a white policeman. Fonny, the sculptor, is innocent, yet it is up to the accused and his family to prove ‘and to pay for proving’ this simple fact.

…

“The novel progresses swiftly and suspensefully, but its dynamic movement is interior. Baldwin constantly understates the horror of his characters’ situation in order to present them as human beings whom disaster has struck, rather than as blacks who have, typically, been victimized by whites and are therefore likely subjects for a novel. The work contains many sympathetic portraits of white people, especially Fonny’s harassed white lawyer, whose position is hardly better that the blacks he defends. And, in a masterly stroke, Tish’s mother travels to Puerto Rico in an attempt to reason with the woman who has accused her prospective son-in-law of rape, only to realize, there, a poverty and helplessness more extreme that that endured by the blacks of New York City.

…

“Yet the novel is ultimately optimistic. It stresses the communal bond between members of an oppressed minority, especially between members of a family, which would probably not be experienced in happier times. As society disintegrates in a collective sense, smaller human unity will become more and more important. Those who are without them, like Fonny’s friend Daniel, will probably not survive. Certainly they will not reproduce themselves. Fonny’s real crime is ‘having his center inside him,’ but this is, ultimately, the means by which he survives. Others are less fortunate.

If Beale Street Could Talk is a moving, painful story. It is so vividly human and so obviously based upon reality, that it strikes us as timeless—an art that has not the slightest need of esthetic tricks, and even less need of fashionable apocalyptic excesses.

1. Bangkok Wakes to Rain by Pitchaya Sudbanthad

2 Rave • 6 Positive

“Pitchaya Sudbanthad’s monumental and polyphonic debut novel is a sweeping epic with the amphibious city of the title at its scintillating center … like raindrops, these stories flow together to make a totality, a stream of narrative that floods the reader with the vibrant sense of a global metropolis whose only constant is constant change … The novel’s texture feels cinematic, but more immersive than a movie, in part because of the evocation of the scents of the setting … In the vein of Arundhati Roy, Haruki Murakami or David Mitchell, Sudbanthad’s elaborate, time-hopping saga explores class stratifications, intercultural connections and disconnections, and finely textured layers of history, all the while raising fascinating questions about the future.”

–Kathleen Rooney (The Star Tribune)

*

=2. Trump Sky Alpha by Mark Doten

2 Rave • 4 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Doten launches Trump Sky Alpha at the bull’s eye of reality with such velocity that it bursts through the other side. This is speculative fiction as burning ring of fire … The beginning is outrageous fantasy but reads like transcription. Doten channels Trump’s verbal tics and rhetorical poverty so perfectly it’s chilling … Perversely satisfying, this tour de force of vicious satire is cathartic … The stress of outperforming realism in works of speculative fiction sometimes risks a dangerous rise in the literary mercury. Both [Doten’s novel, and the novel within the story] suffer from an overreliance on facsimile screenshots and voiceyness … Dizzy with metaphor, Trump Sky Alpha is a cautionary tale for a time when we have become inured to flashing yellow all around.”

–Melissa Holbrook Pierson (The Washington Post)

*

=2. Landfall by Thomas Mallon

2 Rave • 4 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Mallon’s knowledgeable and diamond-hard portraits of actual Washington insiders across the political spectrum, from showboating John Edwards (Mallon’s most acid character sketch) to tough-as-nails Barbara Bush (no sweet little old lady in pearls here). Nonetheless, the fact that Ross and Allie change their views based on experiences on the ground makes a refreshing—and one suspects deliberate—contrast with the dug-in positions of today’s political partisans … Marvelously detailed, often darkly funny, as informative as it is entertaining. Mallon may well be the 21st century’s Anthony Trollope.”

*

4. Rag by Maryse Meijer

3 Rave • 2 Positive • 1 Mixed

“With terse, dark prose, Meijer has created a cohesive set of stories which seem to delight in exploring taboos and destroying expectations … These stories are unsettlingly honest, with the most twisted inner thoughts of each principal character laid bare for the reader. Rag is at its strongest when delving into the minds of its uniformly flawed narrators … The haunting, beautifully horrific stories in Rag linger long after finishing the collection, and subtly answer almost as many questions as they raise about what it means to interact with and be a man in the modern world.”

–Katie O’Neill (ZYZZYVA)

Read an excerpt from Maryse Meijer’s Rag

*

5. The Night Tiger by Yangsze Choo

4 Rave • 1 Mixed

“Complex, ambitious … In less capable hands, this could feel gimmicky. But Choo pulls it off brilliantly, never once slipping into territory that feels silly or coincidental … The magic of The Night Tiger, then, is not in where or what or even who. It is in the why … Choo builds characters that are rich and nuanced, with fully imagined backstories that are revealed slowly as the story builds … a fine example of historical fiction, a work of magical realism, a ghost story, a mystery, a romance, a coming-of-age tale. Each of these is impressive, but most impressive is Choo’s ability to weave them all together in a way that feels authentic, and to use that intricate process to tell a story of colonialism and self-determination, love and death, family and tradition.”

–Kerry McHugh (Shelf Awareness)

**

1. Nobody’s Looking at You by Janet Malcolm

3 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

“It would be frightening to be interviewed by Janet Malcolm. But the same qualities that make her such a fearsome interlocutor also lend her essays an uncommon clarity … Malcolm brings [the] same moral seriousness to every topic she addresses … Yes, Malcolm can be unforgiving. But her calm, brilliant essays are the perfect tonic for our troubled times.”

–Ann Levin (The Associated Press)

Read an excerpt from Nobody’s Looking at You here

*

2. How to Hide an Empire by Daniel Immerwahr

4 Rave • 1 Positive • 2 Mixed

“The book is written in 22 brisk chapters, full of lively characters, dollops of humor, and surprising facts … It entertains and means to do so. But its purpose is quite serious: to shift the way that people think about American history … Immerwahr convincingly argues that the United States looks less like an empire than its European counterparts did not because U.S. policy maintains any inherent commitment to anti-imperialism, but because its empire is disguised first as continuous territory and later by the development of substitutes for formal territorial control … It is a powerful and illuminating economic argument … the book succeeds in its core goal: to recast American history as a history of the ‘Greater United States’ … Immerwahr’s book deserves a wide audience, and it should find one. In making the contours of past power more visible, How to Hide an Empire may help make it possible to imagine future alternatives.”

–Patrick Iber (The New Republic)

Read an excerpt from Daniel Immerwahr here

*

3. Separate: The Story of Plessy V Ferguson by Steve Luxenberg

3 Rave • 2 Positive • 3 Mixed

“The reader’s great honor and delight is to follow Luxenberg as he intertwines their stories from widely singular strands at the beginning, to their historical moments on stage together in 1896 … In explaining the lead-up to the Civil War, Luxenberg offers a clarifying analysis of the catalyzing effects of the Runaway Slave Act, particularly in the North … With this monumental work, Luxenberg shows us precisely how [our current political landscape echoes those of the past]—through the workings of malleable law.”

–Y. S. Fing (The Washington Independent Review of Books)

*

4. Midnight in Chernobyl by Alan Higginbotham

5 Rave • 1 Mixed • 1 Pan

“… chilling … Interviewing eyewitnesses and consulting declassified archives—an official record that was frustratingly meager when it came to certain details and, Higginbotham says, couldn’t always be trusted—he reconstructs the disaster from the ground up, recounting the prelude to it as well as its aftermath. The result is superb, enthralling and necessarily terrifying … Amid so much rich reporting and scrupulous analysis, some major themes emerge … Higginbotham’s extraordinary book is another advance in the long struggle to fill in some of the gaps, bringing much of what was hidden into the light.”

–Jennifer Szalai (The New York Times)

*

5. Good Kids, Bad City by Kyle Swenson

2 Rave • 3 Positive

“Swenson has produced a compelling, beautifully written book that goes well beyond that initial journalistic probe into a grave injustice. Good Kids, Bad City is a powerful addition to the growing literature on the failures of America’s criminal justice system, particularly in dealing with African American men. But it is also a gripping, novelistic account of what happened to the three defendants and their lone accuser after the convictions, a frank confession of the methods and emotions of an obsessed reporter, and a poignant meditation on the dark side of Cleveland and what became of that once-proud embodiment of Midwestern virtues that allowed this travesty to happen.”

–Mark Whittaker (Washington Post)

Climate change prophesies, fictionalized dispatches from the drug-war, and an unusual musician’s memoir are all under the critical spotlight this week.

In her New York Times review of The Border—the final part of Don Winslow’s acclaimed drug-war trilogy—Janet Maslin calls the novel “devastating…a book for dark, rudderless times, an immersion into fear and chaos.”

Over at Slate, Susan Matthews considers David Wallace-Wells’ harrowing investigation into the cataclysmic ramifications of climate change, The Uninhabitable Earth. “In his attempt to explain how climate change will kill,” Matthews writes, “Wallace-Wells does a terrifyingly good job of moving between the specific and the abstract.”

Meanwhile, Vox‘s Constance Grady was deeply impressed by how Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman—in her memoir, Sounds Like Titanic—takes a wacky story about pretend violin playing and turns in into a meditation on gender, economy, and the attitudes of post-9/11 America.

We’ve also got Parul Sehgal of the New York Times on Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (“an exhilarating social history….[of] young black women ‘in open rebellion'”) and the New Yorker‘s Katy Waldman on Chloe Aridjjs’ Sea Monsters, a Sebaldian tale of a young Mexican woman who runs away to a beach community in Oaxaca (“self-contained, inscrutable, and weirdly captivating”).

*

“Of all the blows delivered by Don Winslow’s Cartel trilogy, none may be as devastating as the timing of The Border, its stunner of a conclusion … This is a book for dark, rudderless times, an immersion into fear and chaos. It conjures more lawlessness, dishonesty, conniving, brutality and power mania than both of the earlier books put together. Because of that chaos, it might have benefited from an indexed cast of characters. But Winslow can’t provide one. For one thing, it would be a spoiler. You just have to watch these miscreants as they drop … Winslow describes sting operations with immersive, heart-grabbing intensity. You don’t read these books; you live in them … Last and never least with Winslow: the matter of languages. He is fluent in many of them, and The Border once again shows off those talents … The border ends with another idea about the soul. ‘There is no wall that divides the human soul between its best impulses and its worst.’ Two classic trilogies, The Godfather and now this one, are built upon it.”

–Janet Maslin on Don Winslow’s The Border (The New York Times)

*

“Aridjis is deft at conjuring the teenage swooniness that apprehends meaning below every surface. Like Sebald’s or Cusk’s, her haunted writing patrols its own omissions … Sea Monsters largely consists of Luisa ‘zigzagging’ among beachcombers, nudists, and vagabonds; noting dogs and waves; and meditating on her past life in Roma, the district in Mexico City where she attended a fancy international school on a scholarship. (Most of her classmates had bodyguards.) She waits in vain for something amazing to happen in surroundings that tremble with potential … Sebaldian novels tend toward the paradoxical: they are hypnotic narratives about disenchantment. Something has broken the world, traumatizing the narrator and showering the reader in beguiling fragments. In Austerlitz, the trauma is the Holocaust. Sea Monsters gathers stray observations, bits of ocean treasure, but there is no obvious rupture to explain their suggestive sense of incompletion … The figure of the shipwreck looms large for Aridjis. It becomes a useful lens through which to see this book, which is self-contained, inscrutable, and weirdly captivating, like a salvaged object that wants to return to the sea.”

–Katy Waldman on Chloe Aridjjs’ Sea Monsters (The New Yorker)

*

“Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Saidiya Hartman’s exhilarating social history, begins at the cusp of the 20th century, with young black women ‘in open rebellion’ … Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments is a rich resurrection of a forgotten history, which is Hartman’s specialty. Her work has always examined the great erasures and silences—the lost and suppressed stories of the Middle Passage, of slavery and its long reverberations. Her rigor and restraint give her writing its distinctive electricity and tension. Hartman is a sleuth of the archive; she draws extensively from plantation documents, missionary tracts, whatever traces she can find—but she is vocal about the challenge of using such troubling documents, the risk one runs of reinscribing their authority. Similarly, she is keen to identify moments of defiance and joy in the lives of her subjects, but is wary of the ‘obscene’ project to revise history, to insist upon autonomy where there may have been only survival, ‘to make the narrative of defeat into an opportunity for celebration’ … This kind of beautiful, immersive narration exists for its own sake but it also counteracts the most common depictions of black urban life from this time—the frozen, coerced images, Hartman calls them, most commonly of mothers and children in cramped kitchens and bedrooms.”

–Parul Sehgal on Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (The New York Times)

*

“The bulk of the book is an expanded, horrifying assessment of what we might expect as a result of climate change if we don’t change course. The result is a frightening, compelling text that re-raises the question: In the face of existential threat, what role can storytelling hope to play? Wallace-Wells is an extremely adept storyteller, simultaneously urgent and humane despite the technical difficulty of his subject … The ultimate effect of all of this is to feel as if Wallace-Wells is scanning through the entire world with a sort of overactive bionic eye, zooming in on different problems, calculating the risk, and then zooming back out and over to something else … In his attempt to explain how climate change will kill, Wallace-Wells does a terrifyingly good job of moving between the specific and the abstract … But, as Wallace-Wells points out, 800 million people are already food insecure, and thousands of people drown in floods (and die of asthma, and heat stroke, and forest fires). For me, this frequent reminder of the current baseline was one of the scariest parts of the book. Time’s slippery slowness prevents us from ever fully internalizing how much has already been made worse by climate change … Through the Wallace-Wells climate change–focused lens, industrialized society is a tragedy in which we thought we had built something enduring while really, we had just exploited fossil fuels into a temporary mirage of an empire that would end up drowning the rest of the world … Still, his optimism feels hard to square with the preceding 200 pages of detailed disaster. Ultimately, what I’m left wondering is: Who is this book for, exactly? Wallace-Wells’ response to the critics who argued that he was unproductively scaring people was to correctly point out that there are way more people not alarmed enough about climate change than there are people who are too alarmed. The book, then, is for them. It will undeniably alarm them. What I can’t help but wish is that it also offered them a plan.”

–Susan Matthews on David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth (Slate)

*

“She isn’t just using her experience as a fake violinist as a wacky story. In her hands, it becomes the starting point for bigger issues. She explores questions about gender, and about how and why, as a young woman, she was only able to feel respected when she was playing her violin in front of a crowd. She explores questions about the economy, and how the student debt crisis drove her to keep working as a fake violinist even as it caused her to lose her grasp on the difference between fiction and reality. And more and more as the book goes on, Hindman delves into questions about America’s endless appetite for comforting fakery, and how that desire for comfort played out in the post-9/11 era and the runup to the Iraq War … What Hindman eventually concludes, though, is that America did not want explanation in the years after 9/11. America wanted soothing. And that’s what the violin tour she was faking working at had to offer: It gave the appearance of a live performance of a knockoff of a movie soundtrack about a historical tragedy. And in so doing, it ‘strengthened [Americans’] resolve to believe that even the most shocking national tragedy will evolve over time, become a story told by old women with good senses of humor.’ It was deliberately fake, and it was deliberately bland, and it was comforting.”

–Constance Grady on Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman’s Sounds Like Titanic (Vox)

There are few things the literary community relishes more than the appearance of a polarizing high-profile book. Sure, any author about to release their baby into the wild will be hoping for unqualified praise from all corners, but what the lovers of literary criticism and book twitter aficionados amongst us are generally more interested in is seeing a title (intelligently) savaged and exalted in equal measure. It’s just more fun, dammit, and, ahem, furthermore, it tends to generate a more wide-ranging and interesting discussion around the title in question. With that in mind, welcome to a new series we’re calling Point/Counterpoint, in which we pit two wildly different reviews of the same book—one positive, one negative—against one another and let you decide which makes the stronger case.

From Valeria Luiselli, the two-time National Book Critics Circle finalist and author of Faces in the Crowd and Tell Me How It Ends, comes Lost Children Archive—a new novel about a family whose road trip across America collides with an immigration crises at the southwestern border. Told through several haunted voices, blending texts, sounds, and images, the book is a fascinating hybrid of imaginative storytelling and political fury.

Although Lost Children Archive has garnered overwhelmingly positive reviews—from outlets like the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and NPR, among others—we have also seen one or two dissenting opinions.

Today, we’ll be taking a closer look at one of these, from the Boston Globe‘s Laura Collins-Hughes, who writes that the book “feels like the author fighting with herself,” alongside a rave review by Guernica‘s Rob Spillman, who calls it “…simply stunning…[the] perfect intervention for our horrible time.”

*

…the children will ask, because ask is what children do.

And we’ll need to tell them a beginning, a middle, and an end.

We’ll need to give them an answer, tell them a proper story

“…a semi-autobiographical gloss that Lueselli skillfully crafts without dipping into the pedantic accumulations that sometimes overwhelm such books … This road novel is driven by fierce intelligence, and is very much in conversation with her artistic and intellectual forefathers and foremothers … There are echoes of the Odyssey, Ezra Pound’s Cantos, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and dozens of others, in multiple languages, plus numerous classic American road texts … It is a breathtaking journey, one that builds slowly and confidently until you find yourself in a fever dream of convergences. The Lost Children Archive is simply stunning. It is a perfect intervention for our horrible time, but that fleeting concurrence is not why this book will be read and sampled and riffed on for years to come … The Lost Children Archive contains multitudes, contradictions, and raises difficult questions for which there are no easy answers.”

–Rob Spillman (Guernica)

“…most of the quarreling inside this boxy, aged Volvo, where readers spend much of Valeria Luiselli’s meticulously constructed, stultifyingly cerebral new novel, Lost Children Archive, feels like the author fighting with herself. Luiselli debates and foot-drags over how best to tell the story she really wants to tell—about lost migrant children at the US-Mexico border—and whether she has the right to … Every detail, including the children’s obsession with David Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’ and the boy’s retro birthday gift of a Polaroid camera, is part of Luiselli’s painstaking architecture … For its oxygen-starved first half, structure and literary complexity seem to be of greater interest to Luiselli than storytelling … Luiselli couldn’t fully persuade herself of her right to tell their story—to use her words to help us understand and, yes, feel. Would that she had. Because great art, like great journalism, can in fact move people to action.”

–Laura Collins-Hughes (The Boston Globe)

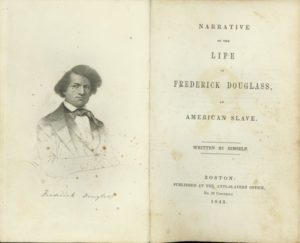

Today marks the one hundred and twenty-forth anniversary of the death of Frederick Douglass. Douglass—who escaped from bondage to become a towering abolitionist, orator, and statesman—penned what is generally considered to be the most iconic and influential slave narrative of the period, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. First published in 1845 to quell doubts about his origins, the memoir was an instant success, selling 5,000 copies within four months and almost 30,000 by 1860.

Now considered a foundation text in the history of American civil rights literature, we thought we’d take a look back at one of the very first reviews of this vital and groundbreaking work.

*

I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the North, to find persons who could speak of the singing among slaves as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears.

“Frederick Douglass has been for some time a prominent member of the Abolition party. He is said to be an excellent speaker—can speak from a thorough personal experience—and has upon the audience, beside, the influence of a strong character and uncommon talents. In the book before us he has put into the story of his life the thoughts, the feelings and the adventures that have been so affecting through the living voice; nor are they less so from the printed page. He has had the courage to name the persons, times and places, thus exposing himself to obvious danger, and setting the seal on his deep convictions as to the religious need of speaking the whole truth. Considered merely as a narrative, we have never read one more simple, true, coherent, and warm with genuine feeling. It is an excellent piece of writing, and on that score to be prized as a specimen of the powers of the Black Race, which Prejudice persists in disputing. We prize highly all evidence of this kind, and it is becoming more abundant. The Cross of the Legion of Honor has just been conferred in France on Dumas and Souliè, both celebrated in the path of light literature. Dumas, whose father was a General in the French Army, is a Mulatto; Souliè, a Quadroon. He went from New-Orleans, where, though to the eye a white man, yet, as known to have African blood in his veins, he could never have enjoyed the privileges due to a human being. Leaving the Land of Freedom, he found himself free to develope the powers that God had given.

…

“We feel that his view, even of those who have injured him most, may be relied upon. He knows how to allow for motives and influences. Upon the subject of Religion, he speaks with great force, and not more than our own sympathies can respond to. The inconsistencies of Slaveholding professors of religion cry to Heaven. We are not disposed to detest, or refuse communion with them. Their blindness is but one form of that prevalent fallacy which substitutes a creed for a faith, a ritual for a life. We have seen too much of this system of atonement not to know that those who adopt it often began with good intentions, and are, at any rate, in their mistakes worthy of the deepest pity. But that is no reason why the truth should not be uttered, trumpet-tongued, about the thing. “Bring no more vain oblations”; sermons must daily be preached anew on that text. Kings, five hundred years ago, built Churches with the spoils of War; Clergymen to-day command Slaves to obey a Gospel which they will not allow them to read, and call themselves Christians amid the curses of their fellow men.—The world ought to get on a little faster than that, if there be really any principle of improvement in it. The Kingdom of Heaven may not at the beginning have dropped seed larger than a mustard-seed, but even from that we had a right to expect a fuller growth than can be believed to exist, when we read such a book as this of Douglass. Unspeakably affecting is the fact that he never saw his mother at all by day-light.

I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.

The following extract presents a suitable answer to the hacknied [sic] argument drawn by the defender of Slavery from the songs of the Slave, and is also a good specimen of the powers of observation and manly heart of the writer. We wish that every one may read his book and see what a mind might have been stifled in bondage,—what a man may be subjected to the insults of spendthrift dandies, or the blows of mercenary brutes, in whom there is no whiteness except of the skin, no humanity except in the outward form, and of whom the Avenger will not fail yet to demand—’Where is thy brother?’ “