I suppose you could take any ten-year period and call it turbulent, but the 2010s have truly been the “hold my beer” of decades. For me personally, I left a toxic work situation, went back to school to earn an MFA, finished a novel, and started a whole new career. For the world outside my own head, I can’t think of time period where more countries went through more radical political shifts, when young people were more socially active, when the climate itself seemed more unstable, or when more works of singular art were produced. Maybe in the early 1800s? But even the Year Without A Summer only lasted that one summer.

Perhaps it’s inevitable then that this decade has produced incredible art? That the artists of this era are working at extraordinary levels to try to do the work of exploring and deconstructing the rollercoaster we’ll all on? I’ve attempted to round up Ten Must-Read SFF Books of the 2010s, but this list could have had fifty other books on it and they’d also be must-reads.

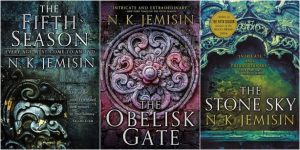

The Broken Earth Trilogy by N.K. Jemisin

(Orbit, 2015, 2016, 2017)

If the 2010s has produced one true Titan of Fantasy, one person who’s going to be carved into a mountain beside Tolkien and Delany and Butler and Jordan, it’s gotta be N. K. Jemisin. The author penned two mammoth trilogies within the last decade, the Inheritance Trilogy and the Broken Earth Trilogy, and it’s the Broken Earth series in its entirety that I’m recommending here. The books address climate disaster, stolen magic, class issues, and slavery, but they also build an incredible, original magic system, and then they give you characters you want to hang out with, and nuanced baddies to hate. Plus they’re super funny, and human, and warm.

Not only did Jemisin become the first Black author to win a Hugo for Best Novel in 2016 for The Fifth Season, but the two subsequent volumes of the trilogy, The Obelisk Gate and The Stone Sky, also won, making her the first author to win the award for three consecutive years. If there’s one author who will serve as an inspiration to the next generation of fantasy writers, it’s N. K. Jemisin.

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers

(Harper Voyager, 2016)

Do you miss ‘90’s Star Trek? Do you love watching a crew of people from a lot of different walks of life learn to work together and grow as people (or, y’know, whatever) while their ship hurtles through the void of space? If yes, you probably want Becky Chambers’ work in your life. Her first novel, The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet was Kickstarted and self-published in 2014 before being republished by Hodder & Stoughton. Chambers introduces readers to Rosemary Harper, a Martian-born human who joins the crew of the tunneling ship Wayfarer in order to ditch her old life. She gets a gig as the ship’s clerk, and tries to fit in with the rest of the shipmates while hiding her past—and why she had to leave it behind.

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet gave the 2010s character-driven sci-fi that made room for lots of different alien species, genderfluidity, characters hooking up in improbable ways, and, most important of all: it chose optimism in the face of the future.

The Martian by Andy Weir

(Broadway Books, 2014)

As Andy Weir’s novel unspools, we realize that the vast majority of it is made up of journal entries that Watney records without even knowing whether another human will see them. Far more than the profane and funny film, the book gets across the utter solitude of the only man on Mars. Best of all (and I never expected to type this sentence), this book is great because of all the math. Where the movie covered a lot of Watney’s survival tactics in a series of montages, Weir can really dig into his careful calculations, and the sense of dark humor and fatalism that creeps in as he realizes he might be, for lack of a better phrase, fucked.

As you read you understand in a much deeper way that this man’s survival comes down to his scientific and creative thinking. I can’t think of a work this decade that took more sheer delight in the power and inventiveness of the human mind.

The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison

(Tor Books, 2014)

I’ll cheat here slightly by saying this is my favorite fantasy book of the decade. I know I shouldn’t play favorites, but I can’t help it. A brief plot synopsis: eighteen-year-old Maia is the fourth, unwanted, half-goblin, straight-up banished son of the elven Emperor Varenechibel IV. When an airship explosion kills his father and all three of his elder brothers, Maia is suddenly left Emperor to a nation of elves who see him as an ugly and uncouth pretender. And, they’re not entirely wrong? Maia’s father never saw fit to give him any of the necessary training in statecraft, history, or even royal etiquette, so when he has to take over a hostile court he has to rely on his wits, empathy, and a sense of moral decency not often found in the rulers of nations.

Reading this book is a full, immersive, comfort-read joy—Addison carefully leads Maia and the reader into complex court intrigue and conspiracies, and we learn along with Maia as he slowly figures out who to trust and how to rule. But can he do it without becoming a tyrant like his father?

Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie

(Orbit, 2013)

The first book in the Imperial Radch series did three amazing things: it messed around with gender in a really fun way; it questioned the very idea of individual identity and personhood; it told a gripping story that spread across generations. In the present-day story, Breq is on a quest for vengeance that gets sidetracked when she has to save an old crewmate. This narrative alternates with flashbacks to cataclysmic events 19 years earlier, when the starship Justice of Toren tried to induct the planet Shis’urna into the Radchaii Empire. Around these two plots, Leckie opens a conversation about gender roles by defaulting to female personal pronouns, and creating a character, Breq, who for various complicated reasons can’t differentiate between genders and has to guess. She asks questions about the nature of consciousness through some characters who are seem like individuals, but are actually arms—ancillaries—of one larger shared consciousness.

While Ancillary Justice might not the best sci-fi for people brand new to the genre, it’s incredibly rewarding once you sink into its world—and for SF fans, watching how Leckie tweaks tropes and conventions makes for a stunning reading experience.

The Changeling by Victor Lavalle

(Spiegel & Grau, 2017)

I reviewed Victor LaValle’s The Changeling upon its release, and I said then that it was one of the best books I’d read that year. In the years since, I can say that there are few books that have stuck with me the way that one has. Two scenes in particular are such indelible setpieces—but hang on, let me give you a plot synopsis. Apollo Kagwa and his wife, Emma Valentine, are sharing a storybook romance. She’s a librarian, he’s a rare book dealer—one of two Black men working in that trade in New York City (the other one is his best friend, Patrice). Apollo and Emma have a beautiful baby together—but then everything falls apart. Emma seems to turn into a different person, distant and filled with rage. Apollo is so haunted by his own father’s abandonment that he’s overcome with an almost obsessive love for his son. And when tragedy hits the young family, Apollo finds himself in the sort of dark, blood-drenched fairy tale that Vikings used to tell around the fire.

At heart this book is a classic bildgungsroman, but it’s a bildungsroman set in a starkly modern New York City, and it centers on a Black man who has to spend as much time grappling with his city’s racism as with all the classic tropes of a quest. It’s about parenthood and emotional labor and how social media destroys our identities. But leaving all the critical analysis aside, what makes this book a must-read is that it’s a beautiful love story tangled together with one of the scariest horror novels I’ve ever read.

Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang

(Vintage, 2010)

This book of short stories is probably best known as “The one that has the story Arrival is based on, in which Amy Adams was robbed of the Oscar yet again,” but it’s much more than that. First of all, that story, “The Story of Your Life,” is a delicate, incandescent exploration of love and grief that unfolds in a different way and with a much different impact than the (excellent, imo) film. But that’s only one classic in a book full of them.

The stories here, including the Nebula Award-winning “Tower of Babylon,” the Sidewise Award-winning “Seventy-Two Letters” and the Hugo, Locus, and Nebula Award-winning “Hell is the Absence of God” are infused with mathematical concepts and conversations about physics. Many of the stories are also probing explorations of the nature of faith, as in “Tower of Babylon,” an account of the construction of the Tower of Babel which does not go as the reader expects; “Division by Zero,” which follows the mental collapse of a mathematician who loses her faith in the consistency of math itself; and “Hell Is the Absence of God,” a novelette that explores the aftershock of an angelic accident in a universe where God, angels, Heaven, and Hell all irrefutably exist. Whatever the subject, the stories are all deep explorations of what it means to be human—and how one can be a feeling, compassionate person in a relentlessly rational universe.

Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by Ruth Franklin

(Liveright, 2016)

I wanted to include at least a little non-fiction here, and I could think of no better book than Ruth Franklin’s comprehensive biography of Shirley Jackson. Jackson’s life was shot through with pain—her mother was an emotionally manipulative nightmare, and her husband, the literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, was a serial adulterer whose behavior certainly didn’t help her struggles with depression. But Jackson fought back with dark wit. She didn’t just raise a family, she wrote two riotous collections of domestic observation—Life Among the Savages: An Uneasy Chronicle and Raising Demons, which sort of turned her into a mid-50s Erma Bombeck…who told reporters she practiced witchcraft (and quite possibly did). She hosted a sparkling and diverse literary circle in her home in Vermont, which included her close friends Ralph and Fanny McConnell Ellison. And, of course, when she wasn’t doing all of that she wrote “The Lottery,” which quickly became one of the most infamous short stories in American literary history, and the greatest haunted house novel of all time in Haunting of Hill House. And that’s just barely scratching the surface of her literary output.

Franklin uses the book not just to excavate the frustrating facts of Jackson’s pre-Second Wave life, but also to make it clear that Jackson was one of the foremost writers of the 20th Century, in any genre or any gender. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life is an indispensable biography for writers, horror fans, and feminist literary critics alike.

The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin, translated by Ken Liu

(Chongqing Press, 2008/Tor Books, 2016)

Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem is the first novel in the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy (the subsequent two books are titled The Dark Forest and Death’s End). This book is a work of hard science fiction i.e. the focus here is on huge ideas and scientific possibility rather than the “softer” science of say, the Becky Chambers book mentioned above. But where Three-Body vaults itself into the pantheon of sci-fi classics is by tying the terror and dread of alien invasion into a decade-spanning look at the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath.

Without giving away too much of the plot: a professor named Ye, whose family was torn apart during the Revolution, receives a message that an alien species called the Trisolarans will invade Earth if they learn of its existence. Because her experiences have made her despise humanity, she teams up with an environmentalist who blames humans for ravaging the Earth (fair point) to try to intentionally court invasion. Years later, a different team of researchers attempt to stop the invasion, or at least prepare for it if it comes.

Three-Body was the first Asian book to win the Hugo for Best Novel and its massive success in China led to a whole new wave of Chinese science fiction that is completely reshaping that country’s publishing industry and reading habits.

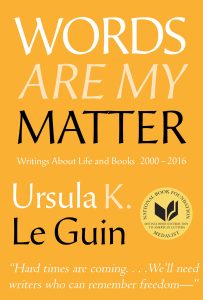

Words Are My Matter by Ursula K. le Guin

(Small Beer Press, 2016)

Le Guin’s decades-long career is the soil from which two generations of SFF have grown. Her stories and novels have nurtured mind upon mind, and it is impossible to overstate her influence on the genre, or the depth of loss the SFF community felt at her passing in 2018. I could have chosen any one of the books she published over the past decade and they’d be worthy of inclusion. I chose Words Are My Matter because it is such a delightfully wide-ranging collection of essays and interviews and it introduces a reader just how expansive Le Guin’s thought process was. It includes her thoughts on authors from Philip K. Dick to Virginia Woolf, as well as a cornucopia of incisive writing advice. It also shows you just how funny she could be, as in this, from the essay “Genre: A Word Only a Frenchman Could Love”:

Re-Fi is a repetitive genre written by unimaginative hacks who rely on mere mimesis. If they had any self-respect they’d be writing memoir, but they’re too lazy to fact-check. Of course I never read Re-Fi. But the kids keep bringing home these garish realistic novels and talking about them, so I know that it’s an incredibly narrow genre, completely centered on one species, full of worn-out clichés and predictable situations—the quest for the father, mother-bashing, obsessive male lust, dysfunctional suburban families, etc., etc. All it’s good for is being made into mass-market movies.

(I’ll admit I have an unrepentant soft spot for Re-Fi, but that still made me blush the first time I read it.) Plus, this book collects her searing 2014 National Book Award speech, here titled “Freedom”:

Books, you know, they’re not just commodities. The profit motive often is in conflict with the aims of art. We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art—the art of words.

I think I’ll end the list on that. Happy New Year, everybody.