Colson Whitehead’s harrowing new novel, George Takei’s graphic memoir of internment, and the story of the lost schoolgirls of Boko Haram are among the most critically-acclaimed books of the past seven days.

*

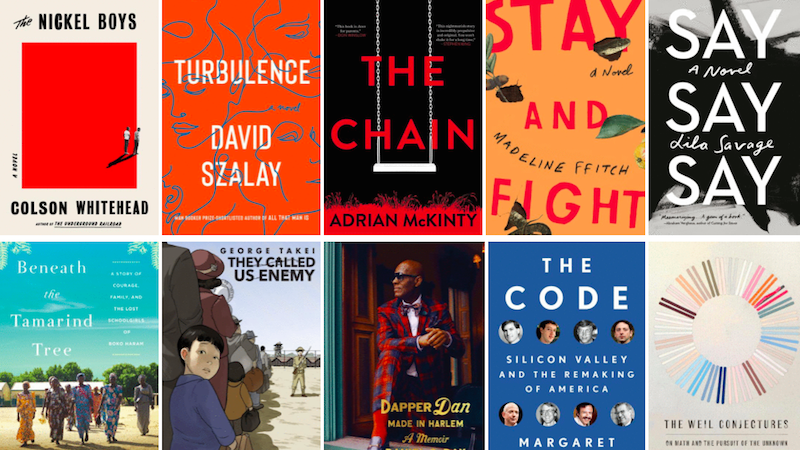

1. The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

20 Rave • 1 Positive • 1 Mixed

“… no mere sequel. Despite its focus on a subsequent chapter of black experience, it’s a surprisingly different kind of novel. The linguistic antics that have long dazzled Whitehead’s readers have been set aside here for a style that feels restrained and transparent. And the plot of The Nickel Boys tolerates no fissures in the fabric of ordinary reality; no surreal intrusions complicate the grim progress of this story. That groundedness in the soil of natural life is, perhaps, an implicit admission that the treatment of African Americans has been so bizarre and grotesque that fantastical enhancements are unnecessary … Whitehead reveals the clandestine atrocities of Nickel Academy with just enough restraint to keep us in a state of wincing dread. He’s superb at creating synecdoches of pain … feels like a smaller novel than The Underground Railroad, but it’s ultimately a tougher one, even a meaner one. It’s in conversation with works by James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison and especially Martin Luther King … what a deeply troubling novel this is. It shreds our easy confidence in the triumph of goodness and leaves in its place a hard and bitter truth about the ongoing American experiment.”

–Ron Charles (The Washington Post)

Read an interview with Colson Whitehead here

The Essential Colson Whitehead

2. Turbulence by David Szalay

7 Rave • 6 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Putting a girdle round the Earth in just 130-odd pages, it’s inevitably a much leaner work, written in a brisk, authoritative past tense rather than a layered and shifting present … There’s not an ounce of fat to be found, as decades of emotion hang in the spaces between the short, declarative sentences … As the stories operate through plot ironies and the sudden illumination of character, this radical simplicity of style means that they offer up most of their pleasures on first reading … What Szalay does so well is the minute-by-minute apprehension of the close-up world, what he calls ‘the tightly packed fabric of reality’, combined here with an impressively global vision … It’s part of Szalay’s genius that he can encompass the distance between the [inspirational and brutal irony].”

–Justine Jordan (The Guardian)

3. The Chain by Adrian McKinty

6 Rave • 5 Positive • 1 Mixed

“[McKinty] has proven a dozen times over that he knows how to write people enduring long-term trauma of terrorism, occupation, and kidnapping without cheapening the reality of it. And he brings that experience and talent fully to bear upon the reader with The Chain … McKinty doesn’t use any tricks of the trade to make this story more relentless than it needs to be…He doesn’t eschew the poetics and embrace of the classical that make the Sean Duffy novels so enjoyable, but he gives the scenes the drive they are due … harrowing and memorable … So many stories treat trauma cheaply, like a scrape where whiskey serves as Bactine, but McKinty does not … gives the reader just enough remove to be entertained and chilled, instead of traumatized … gives us villains that are all too real … a thriller I loved.”

–Thomas Pluck (Criminal Element)

4. Stay and Fight by Madeline Ffitch

5 Rave • 4 Positive

“What comes to mind when you hear the word Appalachia? Whatever it is, it probably won’t be the same after you read this engrossing, sometimes shocking and often witty debut novel … remarkable … Ffitch’s survival saga of strong, independent women will appeal to readers of Dorothy Allison’s Bastard out of Carolina and the realistic novels by Manette Ansay, especially Vinegar Hill.”

–Deborah Donovan (BookPage)

Read Madeline Ffitch’s essay “The Problem of Neoliberal Realism in Contemporary Fiction” here

5. Say Say Say by Lila Savage

6 Rave • 2 Mixed

“What Savage has created is extremely rare in the pages of contemporary fiction: a millennial woman narrator whose mind is not broken … Page after page, we simply sit with Ella as she sits with Jill. And yet the book is never dull, because Savage continually draws and redraws her heroine’s emotional attachments like an ever-evolving diagram … surgically well-expressed … In writing the character of Ella, Savage offers us a political argument: that women who labor in the home and principally care for others can grow in intellectual value because of, not in spite of, their occupations … Savage creates new configurations of women’s self-love, based on human connection. One of those women may be damaged by brain injury and unable to speak, but there is still enough care to keep the flame alive.”

–Josephine Livingstone (The New Republic)

*

1. Beneath the Tamarind Tree: A True Story of Courage, Family, and the Lost Schoolgirls of Boko Haram by Isha Sesay

3 Rave • 4 Positive • 1 Mixed

“In Beneath the Tamarind Tree, Sesay combines the released Chibok girls’ stories with her own journalistic experiences to powerful effect. Sesay is a briskly opinionated writer, and from the first chapters Beneath the Tamarind Tree presents a forceful combination of reportage and social analysis … Where Beneath the Tamarind Tree sets itself apart is in its exploration of the Nigerian government and the international media’s complicity in silencing the Chibok girls’ voices, and those of their parents and of the Nigerian activists fighting for their release.”

–Lily Meyer (NPR)

2. They Called Us Enemy by George Takei

2 Rave • 5 Positive

“…a riveting graphic novel-memoir … Enemy deserves to be a popular recommendation at school libraries across the land—humanizing a brutal chapter in U.S. history that even many adults seem to understand only vaguely … At 82, Takei has evolved into an increasingly powerful voice for oppressed communities, and Enemy finds him at peak moral clarity — an unflinching force in these divisive times. Young readers would do well to learn his story of a childhood set against a historically racist backdrop, told in clear and unmuddled prose. As our politicians trade semantics, They Called Us Enemy calls upon readers to see past the walls, cages and words that divide us.”

–Michael Canva (The Washington Post)

3. Dapper Dan: Made in Harlem by Daniel R. Day

3 Rave • 3 Positive

“Fashion fans might come to this memoir expecting a primer on the journey from street style to couture, and there is certainly a bit of that in the book … Detailed descriptions of his family’s tragic journey through poverty, the changing nature of his beloved and cursed neighborhood, and his adventures as a hustler are riveting. His recollections of his early career as a master gambler and the characters he met along the way, as well as his examination of the psychology of the profession, are perhaps even more compelling.”

–Nelson George (The New York Times Book Review)

4. The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America by Margaret O’Mara

2 Rave • 4 Positive

“… accessible yet sophisticated … An academic historian blessed with a journalist’s prose, O’Mara focuses less on the actual technology than on the people and policies that ensured its success … This is one of O’Mara’s strongest narrative threads: the casual misogyny that has defined Silicon Valley from past to present. She manages to bring the few women who did succeed to the forefront, most notably the programmer and entrepreneur Ann Hardy, who battled systemic sexism even as she wrote the code for many of the first computer time-sharing and networking applications built by the company known as Tymshare … O’Mara toggles deftly between character studies and the larger regulatory and political milieu.”

–Stephen Mihm (The New York Times Book Review)

5. The Weil Conjectures: On Math and the Pursuit of Knowledge by Karen Olsson

5 Positive

“… the story of André and Simone Weil has the quality of a fairy tale—not the chirpy Disney kind but the Brothers Grimm kind. It’s disturbing and strange … Ms. Olsson is enthralled. Drawing on the Weils’ writings and letters, she traces their intellectual tug of war as it played out against the backdrop of war-torn Europe. But this isn’t a biography in the traditional mold. Ms. Olsson, a journalist and novelist, layers in reflections on the history of mathematics and the nature of the unknown. The story builds with the poetry and precision of a theorem, shifting intermittently into memoir as her quest to understand the Weils recalls her own youthful obsession with math … one longs for Ms. Olsson to pursue her intriguing theory a little further … How does gender alter the equation of genius, the search for truth?”

–Elizabeth Winkler (The Wall Street Journal)