2019 wasn’t a great year for culture critics. We lost publications like Pacific Standard, Tin House, and Topic. We were targeted and trolled by fans of Lana Del Rey, Lizzo, Ariana Grande, Michael Che, Amanda Palmer, and other celebrities who took issue with less-than-glowing press. And we saw Richard Ford’s despicable response to a negative review rewarded with lifetime achievement honors.

Nonetheless, 2019 was a great year for books, and for insightful conversations about them. At the risk of making a list for the people most fatigued by lists, here are the best book reviews of the year.

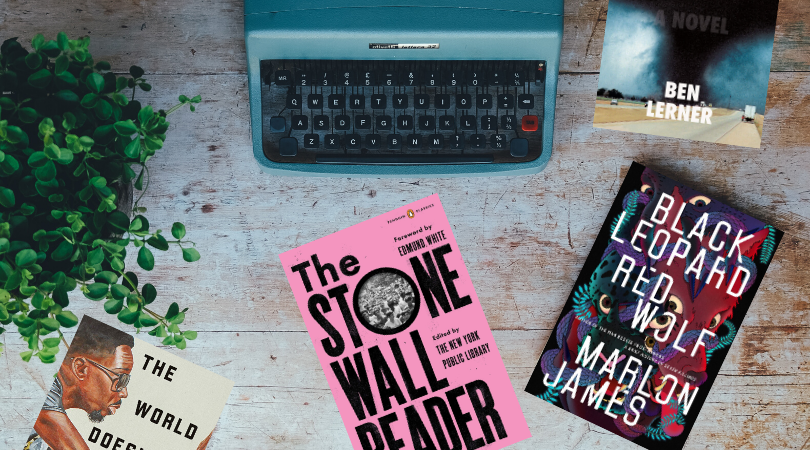

Amal El-Mohtar on Marlon James’ Black Leopard, Red Wolf (NPR)

Black Leopard, Red Wolf is a difficult book to even describe, much less review, but El-Mohtar distills her complicated response into purified prose.

“Reading Black Leopard, Red Wolf was like being slowly eaten by a bear, one inviting me to feel every pressure of tooth and claw tearing into me, asking me to contemplate the intimacy of violation and occasionally cracking a joke. It was a harrowing, horrible experience I’m not keen to repeat. But I can’t deny that having finished it, I went back to the beginning to find things I now better understood, felt better able to withstand—as if in hollowing me out the book had made space for itself, had given me something in exchange for everything it put me through. I don’t know what that is yet. But I have nothing else like it.”

Kathleen Rooney on Jonathan Carr’s Make Me a City (The New York Times Book Review)

As a reader and a critic, Rooney has an investigative spirit, so her reviews are often grounded by a compelling question or two. In this case, why a British novelist would refashion historical figures and events from 19th-century Chicago into a bizarre fictional pastiche.

“If Make Me a City really had been written in 1902, then it would be an extraordinarily forward-thinking and valuable corrective to the erasure of the contributions of women, immigrants and people of color to America’s ‘second city.’ As it is, Carr’s ambitious and presumably well-intentioned tome comes across as pandering, self-satisfied and ultimately wrongheaded.”

Alexander Chee on James Polchin’s Indecent Advances, Perry N. Halkitis’s Out in Time, and the New York Public Library’s The Stonewall Reader (The New Republic)

Some of the compelling criticism is the result of a critic with a personal connection to the book’s subject matter, as is the case with Chee and the Stonewall Inn.

“After reading three books that mark the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall, I have been corrected again, in some way I never anticipated. The militancy I felt as a young man grew from this tradition of remembering the riots without the real story of the riots, just as the distance I felt came from a political narrative whose imagery centered on whiteness and assimilation.”

Constance Grady on Tamsyn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth (Vox)

Grady’s naturalistic criticism is always a joy to read, but this review accomplished something rare: It compelled me to buy the book instantly, without reading anything else.

“It’s an incredibly immersive book, with a rich, detailed mythology, gorgeously balanced sentences, and a genuinely meaningful central relationship. I started this book chuckling at the outrageous premise. I finished it crying, because the ending punched me straight in the gut.”

Gabrielle Bellot on Tillie Walden’s On a Sunbeam (Lit Hub)

Bellot is extremely talented at seeing books through a historical lens, so much so I can only imagine she reads four or five books before reviewing one. In this case, she also opens with a stunning second-person lede.

“Sometimes, you come across a piece of art that lingers. You can’t stop looking at it, reading it, thinking about it, the first time you dive into it; later, it comes back to you, and it makes you smile. You don’t remember it for its simplistic shock value; it shocks you, instead, in a quieter way, because it has formed a connection, a relationship, with you.”

Michael Schaub on Rion Amilcar Scott’s The World Doesn’t Require You (NPR)

Short story collections are very hard to review well, especially when they’re promiscuous with form and genre, but Schaub has taken on the mantle of the late Alan Cheuse as one of NPR’s most versatile and readable critics.

“The book is less a collection of short stories than it is an ethereal atlas of a world that’s both wholly original and disturbingly familiar; Scott proves to be immensely talented at conjuring an alternate reality that looks like an amplified version of our own. Bizarre, tender and brilliantly imagined, The World Doesn’t Require You isn’t just one of the most inventive books of the year, it’s also one of the best.”

Parul Sehgal on Colson Whitehead’s The Nickel Boys (The New York Times Book Review)

For my money, Sehgal is the best lede writer in the business. Like a river through the mountains, she finds the path of least resistance into a book and guides you by the arm. She also does an excellent job layering her criticism with context from interviews, reportage, and other reading.

“‘The dirt looked wrong.’ A college student noticed it first: a sunken patch in a field, near a shuttered juvenile reformatory school. When the scrub was cleared away, and the broken glass, those who were digging hit bone. The skeletons of more than 50 boys were unearthed, rib cages blasted by buckshot.”

Amy Brady on Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School (Slate)

As a native Topekan, Brady brings a unique perspective to Lerner’s third novel in this piece that combines criticism, memoir, and history.

“By almost every marker, we were middle-class white kids with bright futures. But beyond our privileged front doors was a city stewing in poverty, racism, and radical homophobia.”

Andrea Long Chu on Bret Easton Ellis’ White (Bookforum)

The most unnecessary book of the year produced one of my favorite reviews, so perhaps it was all worth it in the end. A more vicious critic could have easily written an acrid rebuttal, but as Chu notes, that would require “taking the bait.”

“I could write an incensed review that fiercely rebuts White’s many inflammatory claims, thus giving the impression that they should be taken seriously; if my review were to go viral, it would likely trigger more bad coverage on pop-culture websites like Vulture and Vice; Bret Easton Ellis might trend for a bit on Twitter, where we would all take our best shots at dunking on this dude; and at the end of it all, the author would get to feel relevant again, and maybe finally write a movie that people actually liked. But why bother?”

Sophie Gilbert on E. L. James’ The Mister (The Atlantic)

Good critics know there’s a time and a place for a no-holds-barred pan: when a book is so bad, it’s actively doing harm. You can feel the heat coming off this one.

“Nora Roberts is writing books about female firefighters and hostage negotiators. The pervasive whiteness of romance is finally being challenged. Stories like The Mister, which seem to want to wrench female sexuality and status back into the realm of feudalism, have a long distance to go to catch up.”