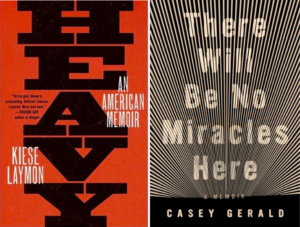

In a moving tribute to the life and work of the late Max Ritvo, who died in 2016 at the age of twenty-five, the New Yorker‘s Dan Chiasson considers the poems of The Final Voicemails and how they “envision countless afterlives, each one more arresting than the last.” Over at NPR, Annalisa Quinn reads Stormy Daniels’ much-publicized sex-with-Trump tell-all, Full Disclosure, as “a canny Trojan horse of a book,” one which “baits readers with the salacious details of her alleged time with Trump, but instead offers a jaunty, foul-mouthed treatment of her life.” In her New York Times review of Crudo—Olivia Laing’s experimental, autofictional, Kathy Acker-channeling debut novel—A Separation author Katie Kitamura writes that the book “begins as a piece of conceptual swagger, only to morph into something far more intimate and in some ways more exceptional.” We’ve also got Josephine Livingstone’s New Republic take on Tana French’s latest Irish thriller, The Witch Elm, and Christopher J. LeBron’s consideration of two memoirs which focus on the costs of succeeding while black in America: Kiese Laymon’s Heavy and Casey Gerald’s There Will Be No Miracles Here.

*

“I never met Max Ritvo, but in the years that followed I felt that I came to know him: his friendly curiosity, his wit and preternatural lyric gifts, and, terribly, his illness. Given a diagnosis of Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare form of cancer, when he was sixteen, Ritvo died in 2016, at the age of twenty-five. His emergence as a writer was, in fact, a record of his imminent disappearance. He was making himself unforgettable, one vivid trace at a time … The term ‘voice mail’ modernizes a classic understanding of lyric poetry, similar to the way Dickinson’s sense of her poems as unprompted ‘letters to the world’ did. Like a voice mail, a poem is a performance that anticipates a response, shaped for a specific but absent audience: by the time it reaches its recipients, the author will have moved on. But, after death, it can be ‘played back’ on an infinite loop, a material but fragile manifestation of voice. It is short, because we know the tape runs out. Everywhere in this book we confront realities too dismal for lyric transformation, nevertheless uncannily transformed … These poems envision countless afterlives, each one more arresting than the last … These poems envision countless afterlives, each one more arresting than the last … Ritvo is now permanently located, and obliquely revealed, in his poems. It’s we, his readers, who come and go. When we close [this book], we miss him.

–Dan Chiasson on Max Ritvo’s The Final Voicemails (The New Yorker)

*

“Kiese Laymon and Casey Gerald made it into elite university rooms, all the way from poverty in the ever-present shadow of violence, and their pages are propelled, as Laymon writes in Heavy, by a ‘desire to reckon with the weight of where we’ve been’—to stop ‘paying for white folks’ feelings with a generic smile and manufactured excellence they could not give one fuck about,’ in the parlance of his 17-year-old self … Both books take on the important work of exposing the damage done to America, especially its black population, by the failure to confront the myths, half-truths, and lies at the foundation of the success stories that the nation worships. In the process, Laymon and Gerald dramatize a very different route to victory: the quest to forge a self by speaking hard truths, resisting exploitation, and absorbing with grace the cost of being black in America while struggling to live a life of virtue.”

–Christopher J. LeBron on Kiese Laymon’s Heavy and Casey Gerald’s There Will Be No Miracles Here (The Atlantic)

*

“Written with bristling intelligence, Crudo borrows liberally from Acker, a formal tribute to a master of appropriation. Laing drops unattributed quotes from Acker and others into her text (although they’re cited later, in an appendix). She also uses Acker’s technique of inhabiting multiple voices and identities, all contained within a single character—the ‘I’ and the ‘Kathy’ of those first sentences … Where Acker’s fiction is full of hard juxtapositions and divided selves—pirates and postpunk feminists, Jackie Kennedy and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec—Crudo revolves around a less extreme but equally crucial disjunction: between the ordinary life of Olivia Laing in 2017 and the extraordinary life of Kathy Acker in the second half of the last century. This fissure of identity and voice is used not to stage a ‘model of schizophrenia’ but to explore quieter states of anxiety and discontent … But the larger questions that haunt the book are ‘Why Acker?’ and ‘Why now?’ Laing doesn’t try to make the case that Acker—a remarkably transgressive but also a remarkably privileged individual—is the voice best positioned to critique or represent these times. Instead, the impulse to resurrect Acker feels more personal. Crudo begins as a piece of conceptual swagger, only to morph into something far more intimate and in some ways more exceptional.”

–Katie Kitamura on Olivia Laing’s Crudo (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“In the past two years, Daniels has stopped being a person and started being shorthand. To Trump and his team, she’s a threat to the presidency. To his detractors, she is a personification of all the sordidness that clings to Donald Trump—affairs, money and sleaze. Stormy Daniels knows this, and her memoir Full Disclosure is a canny Trojan horse of a book. She knows exactly why you are reading it and—a career entertainer—gives the people what they want: that is, ‘two to three minutes’ and ‘smaller than average.’ But those pieces are buried deep in the book (At which point Daniels asks, ‘Okay, so did you just skip to this chapter?’). She baits readers with the salacious details of her alleged time with Trump, but instead offers a jaunty, foul-mouthed treatment of her life, from a childhood growing up in poverty in Louisiana to the world of clubs and porn sets. Above all, she is out to prove that she is much more than ‘two to three minutes’ with Donald Trump … Full Disclosure is more flashy than thoughtful, and Daniels rarely interrogates herself or her industry. I would have liked, for instance, to hear her thoughts on the ethics of porn. She also doesn’t quite explain why she (allegedly) slept with Trump, whom she clearly found repulsive. She seems to take a parade of creeps as part of life, as inevitable and uninteresting as traffic jams … Full Disclosure, with its carefully spaced revelations and its emphasis on the larger context of Daniels’ life and work, is the product of someone fighting to stay in control of a story—perhaps in part because she is so used to being written off.”

–Annalisa Quinn on Stormy Daniels’ Full Disclosure (NPR)

*

“In a 2016 New Yorker piece about French, Laura Miller explained the connection between crime stories and the communities they’re set in: ‘All crime novels are social novels. They can’t help it; without a society to define, condemn, and punish it, crime itself wouldn’t exist.’ In the case of The Witch Elm, French offers an analysis of how privilege (and the lack of it) defines a person’s experience of life … French’s accomplishment is in turning the classic mystery novel ingredients—contradictory accounts, unreliable memory, dark family secrets—into a narrative about politics. We are aware that the main character can be somewhat entitled, but also that he is suffering from a brain injury. French invites the reader to make assumptions about his competency, to treat him as an unreliable narrator, because of his condition. So, French’s readers are drawn into a complex tangle of ethics in which they are forced to question a disabled person’s perspective as a direct result of his disability … The Witch Elm is a profound reconsideration of power dynamics between the privileged and the less so, drawing the reader into an uneasy alliance with the former. It’s also a thrilling, absorbing mystery, sprinkled liberally with red herrings and culminating in a profoundly satisfying, if totally unforeseeable, ending.”

–Josephine Livingstone on Tana French’s The Witch Elm (The New Republic)