Each month, for your literary listening pleasure, our friends at AudioFile Magazine bring us the cream of the audiobook crop.

This month’s feast of fantastic audiobooks includes Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman: Act III (read by the author and a full cast including James McAvoy, Kat Dennings, and Wil Wheaton), Adam Hochschild’s American Midnight (read by Jonathan Todd Ross), and George Saunders’ Liberation Day (read by the author and a full cast including Tina Fey, Michael McKean, and Jenny Slate).

*

FICTION

The Sandman: Act III by Neil Gaiman, Dirk Maggs | Read by Neil Gaiman, James McAvoy, K.J. Apa, Kat Dennings, Shruti Haasan, David Harewood, Regé-Jean Page, Kristen Schaal, Wil Wheaton, and a Full Cast

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Audible, Inc. | 11.5 hrs.]

Neil Gaiman lends his enchanting voice to the narration of this acclaimed graphic novel series. This epic drama, written by Gaiman and adapted by audio producer Dirk Maggs, plunges listeners into a fully realized world with dynamic sound effects and impressive vocal performances from a five-star cast. James McAvoy flawlessly portrays Morpheus, the Lord of Dreams, as he and Delirium search for their elusive brother, who renounced his role in the Endless. Each episode may enlighten, amaze, or appall but will undoubtedly entertain.

The Bullet That Missed: Thursday Murder Club, Book 3 by Richard Osman | Read by Fiona Shaw, Richard Osman, Steph McGovern [Interview]

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Penguin Audio | 11.25 hrs.]

The great Fiona Shaw’s performance of this third outing for the Thursday Murder Club is a multilayered joy. New to the series? Start here; start anywhere. You’ll catch right up. Shaw’s technique is impeccable as she delivers the deliciously funny dialogue of Osman’s elderly characters. Just for instance, late in the plot, sweet, fluttery little Joyce finds a 6’7” Swedish thug in her house aiming a gun at her and promising to shoot. Shaw’s disarming performance of her unflappable reaction will make you laugh out loud. The whole production is a comic marvel.

We Are the Light by Matthew Quick | Read by Luke Kirby

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Simon & Schuster Audio | 6.25 hrs.]

Matthew Quick’s latest novel, told through letters written by Lucas Goodgame, is brought to life by Luke Kirby’s heartrending narration. Kirby is the voice of Lucas, who is reading letters written to Karl, his Jungian analyst, as Lucas tries to cope with the tragedy that shattered his life and the lives of all the citizens of Majestic, Pennsylvania. Kirby speaks with wonder as Lucas recounts events that reaffirm how forgiveness and the support of community can rekindle hope and healing.

The Family Izquierdo: Stories by Rubén Degollado | Read by Rogelio T. Ramos, Thom Rivera, Kyla Garcia, Frankie Corzo, Roxanne Hernandez, Carolina Hoyos

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Blackstone Audio | 8 hrs.]

A luminous ensemble brings this delectable audiobook to life. Listeners follow three generations of the Izquierdo family. In 1958, Papa Tavo and Guadalupe moved from Reynosa to McAllen. The Izquierdos are sure a neighbor has placed a curse on them. They attribute all their sadness or bad luck to the curse. But not all the Izquierdos believe in this curse; listeners get a chance to hear different perspectives from various family members. The narrators are consummate professionals, creating a rich and rewarding listening experience.

Liberation Day: Stories by George Saunders | Read by George Saunders, Tina Fey, Michael McKean, Edi Patterson, Jenny Slate, Jack McBrayer, Melora Hardin, Stephen Root

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Random House Audio | 7 hrs.]

George Saunders has won many awards for his writing. His skill as an author and as a narrator is on display here. He delivers the first and last stories in this audio collection, bookending an excellent cast. All nine of the stories focus on people with problematic identities, and each narrator embodies his or her protagonist’s particular problem in an appropriate and evocative way. There are elements of science fiction and fantasy, but they never lose touch with relatable human experience, even in (so far) completely impossible circumstances. Excellent performances of excellent stories.

**

NONFICTION

Visual Thinking: The Hidden Gifts of People Who Think in Pictures, Patterns, and Abstractions by Temple Grandin | Read by Andrea Gallo, Temple Grandin

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Penguin Audio | 12.5 hrs.]

Andrea Gallo delivers a graceful performance that makes this important audiobook a joy to hear. Her lithe phrasing patterns bring a softer quality to the straightforward writing, while her mature pacing and tonal quality give listeners a notable connection with the 75-year-old author’s message and personal stories. Grandin draws listeners into the perceptual world of an autistic animal science engineer whose visual/spatial thinking patterns have put her at odds with language-based thinkers her entire life. A moving and personal audiobook.

American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis by Adam Hochschild | Read by Jonathan Todd Ross

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Harper Audio | 15 hrs.]

Narrator Jonathan Todd Ross has a particular gift for making topics of narrow interest palatable for general listeners. Few eras in American history are as unpalatable as that ignited by WWI and extending into the 1920s, a time when unchecked racism, union opposition, and patriotic fervor stoked violence. None of it makes for easy listening, but this is undoubtedly one of this year’s best and most important histories, narrated with impressive skill, balance, and restraint. The many links to our own uneasy present are implicit, and the evil precedents described here are critical history that bears on dozens of relevant issues today.

Solito: A Memoir by Javier Zamora | Read by Javier Zamora

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Random House Audio | 17.5 hrs.]

Javier Zamora narrates his memoir with a singular power. His account of his childhood migration from El Salvador to the U.S. provides listeners the truly heartbreaking first-person experiences of a child in the midst of a life-or-death struggle. In 1999, Zamora traveled thousands of miles, with a group of strangers, through Central America and Mexico. His parents, already in the U.S., had no ability to contact him, and Zamora misses his parents and longs to hear their voice. Zamora conveys this heartrending listening experience with quiet, beautiful humanity.

Dinners With Ruth: A Memoir of Friendship by Nina Totenberg | Read by Nina Totenberg

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Simon & Schuster Audio | 9.5 hrs.]

Nina Totenberg’s remarkable memoir about friendship, love, fortitude, and the marvelous Ruth Bader Ginsberg is a gift to each woman’s multitudinous fans. Listeners will be moved by Totenberg’s affecting, wise, and often funny reflections on loving the people we love. Narrated by the author, a renowned journalist and NPR legal reporter, the audiobook is performed with Totenberg’s trademark energy, attentive pacing, smart tonal shifts, and talent for reproducing lively conversations. The work combines memoir, social commentary, and philosophical considerations, and violin interludes played by the author’s father, the late superstar Roman Totenberg, are the perfect icing on this delicious cake.

Raising Lazarus: Hope, Justice, and the Future of America’s Overdose Crisis by Beth Macy | Read by Beth Macy

AudioFile Earphones Award

[Hachette Audio | 10.5 hrs.]

Few works bring home the realities, the sadness, and the politics of the opioid crisis as well as this audiobook. Narrated with conviction by author Beth Macy, this firsthand account presents the victims and the unsung heroes who fight valiantly to help them and to bring about meaningful change in a system created for profit, not health. Macy’s performance hits every note, from the emotional torment that strikes families to the outrage against the companies and others that enable and facilitate it.

Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts, George Saunders’ Liberation Day, Paul Newman’s The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man, and Annie Ernaux’s Getting Lost all feature among October’s best reviewed books.

1. Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng

(Penguin Press)

18 Rave • 3 Positive • 3 Mixed

Listen to an interview with Celeste Ng here

“Stunning … One of Ng’s most poignant tricks in this novel is to bury its central tragedy…in the middle of the action. This raises the narrative from the specific story of a confused boy and his defeated father to a reflection on the universal bond between parents and children … Our Missing Hearts will land differently for individual readers. One element we shouldn’t miss is Ng’s bold reversal of the biblical story of the Tower of Babel. It is the drive for conformity, the suppression of our glorious cacophony, that will doom us. And it is the expression of individual souls that will save us.”

–Bethanne Patrick (The Los Angeles Times)

2. The Hero of This Book by Elizabeth McCracken

(Ecco)

16 Rave • 4 Positive

Listen to an interview with Elizabeth McCracken here

“… soulful, melancholy … McCracken deftly evokes how so many of us feel about our mothers: that they are just there, and always there, and that any intimation that they were not always there or weren’t ever just as they are is an affront to the primacy of their connection to their child. Many children will never forget the moment they realized that their mother was a separate human being, who made mistakes and had faults and foibles all their own, separate from their own selves. This existential shock reverberates throughout McCracken’s book, coupled with the shock of that mother no longer being there … In this vivid composition, McCracken paints the final layer of the portrait of the mother she has so painstakingly drawn in the preceding pages … ‘Don’t trust a writer who gives out advice,’ McCracken warns in the first chapter. But the irony is, her words create an exquisite alchemy that makes a reader ready to follow her anywhere, believe every word she writes down. Is this book a novel or is it a memoir? It matters not at all. With every vital, potent sentence, McCracken conveys the electric and primal nature of that first fundamental love.”

–Janice Y.K. Lee (The New York Times Book Review)

3. Liberation Day by George Saunders

(Random House)

15 Rave • 3 Positive • 2 Mixed

Read George Saunders on reading chaotically and the power of generous teachers, here

“Acutely relevant … Let’s bask in this new collection of short stories, which is how many of us first discovered him and where he excels like no other … Saunders’ imaginative capacity is on full display … Liberation Day carries echoes of Saunders’ previous work, but the ideas in this collection are more complex and nuanced, perhaps reflecting the new complexities of this brave new world of ours. The title story is only one of a handful of the nine stories in this collection that show us our collective and personal dilemmas, but in reading the problems so expressed—with compassion and humanity—our spirits are raised and perhaps healed. Part of the Saunders elixir is that we feel more empathetic after reading his work.”

–Scott Laughlin (The San Francisco Chronicle)

**

1. The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World by Jonathan Freedland

(Harper)

11 Rave • 1 Positive

“Compelling … We know about Auschwitz. We know what happened there. But Freedland, with his strong, clear prose and vivid details, makes us feel it, and the first half of this book is not an easy read. The chillingly efficient mass murder of thousands of people is harrowing enough, but Freedland tells us stories of individual evils as well that are almost harder to take … His matter-of-fact tone makes it bearable for us to continue to read … The Escape Artist is riveting history, eloquently written and scrupulously researched. Rosenberg’s brilliance, courage and fortitude are nothing short of amazing.”

–Laurie Hertzel (The Star Tribune)

2. The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man by Paul Newman

(Knopf)

6 Rave • 5 Positive • 2 Mixed

“Newman at his best … The end product…is twice the book one could have dared to hope for, a narrative that is astute, introspective and surprisingly graceful … When we meet our heroes on the page, we want them to have something thoughtful to say—to make good on the admiration their outsize performances have won. Newman always seemed likely to pass that test, with his self-aware persona, storied marriage and generous charitable activities. Still, to see it come true in this rich book somehow imbues his characters’ pain and joy with fresh technicolor.”

–Michael O’Donnell (The Wall Street Journal)

3. Getting Lost by Annie Ernaux

(Seven Stories Press)

9 Rave • 2 Postitive • 1 Pan

“The journal is relentless in its presentation of her pain and abasement, but no less so in its effort to dissect what just happened. Here is the same deep probing for truth, the same fanatical quest for self-awareness to be found in all Ernaux’s work … Like most diaries—and quite unlike Ernaux’s usual meticulously concise prose—Getting Lost contains its share of banalities, messy thoughts, inconsistencies, and unpolished sentences. It is often repetitious, and accounts of Ernaux’s dreams are no more exciting to hear about than anyone else’s ever are. But, to echo James Wood’s observation about reading Karl Ove Knausgaard—another writer consumed with his own intimate history—even when I was bored I was interested … What is remarkable—and what, for me, makes her work more engaging than much contemporary autofiction is her ability to appear removed from her first-person narratives, to be writing objectively about her subjectivity, achieving transparency and, at the same time, an almost forensic detachment … as a matador-writer Ernaux has always faced the bull’s horns. She is a master of close and graceful capework, and, as in any bullfight, it is the show of courage before danger and possible disaster that enthralls the spectator.”

–Sigrid Nunez (The New York Review of Books)

Our trove of terrific reviews this week includes Adam Rivett on Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger, Leo Robson on John Banville’s The Singularities, Ron Charles on Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, Chris Megerian on John A. Farrell’s Ted Kennedy: A Life, and Molly Young on the novels of Philip K. Dick.

“… a sprawling, surreal affair, a book as strange as any he’s ever written, and reminiscent of the melancholy drift and God-haunted monologues of McCarthy’s earliest novels, published half a lifetime ago. While in precis a thriller, this isn’t No Old Country For Old Men. No gun is fired, no blade drawn from its sheath. This is more digression than headlong chase … Almost everything about the novel’s first hundred pages generates expectations for something tough, lean and violent…And then—beautifully, mysteriously, and somewhat bafflingly—we get another book entirely … Even while flouting expectations, McCarthy’s fundamentals remain undeniable. He’s a writer of both wonderfully taut and often very funny dialogue, and this is a book full of talk, bouncing from jokey drunk chat to near-baffling stretches of monologic erudition … Above all else, he is a prose stylist without peer … On almost every page some Faulknerian dazzle finds you, and while his language verges on the purple or overripe, it’s thrilling to return to writing as unashamedly biblical and rhetorical as this, when compared with the dutiful sentences and sturdy, balanced paragraphs of contemporary prose … Less successful is the book’s occasional dabbling with mathematics and physics … The novel comes to life most vividly when it drops this baggage and instead of gesturing towards darkness, embodies it through Bobby … Perhaps fittingly for a book about someone driven to stasis by mourning, the book feels inside out, forever discussing people not there, matters from the past half-explained. Both Bobby and finally the book feel a little withholding, as if we’ve been granted permission to only witness loss, without directly accessing its source.”

–Adam Rivett on Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger (The Sydney Morning Herald)

“The Irish novelist John Banville writes prose of such luscious elegance that it’s all too easy to view his work as an aesthetic project, an exercise in pleasure giving…But what drives Banville—and his relentless hunt for the ideal adjective and simile and cadence—is a desire to touch something elusive and not quite nameable while providing a parallel or overlapping commentary on that doomed but never pointless effort. Although he is often compared to Nabokov, with particular reference to his arch and swaggering narrators, and an emphasis on doubles, Banville’s most important debts are to literary-minded German thinkers (Nietzsche, Heidegger), philosophically inclined German writers (Kleist, Rilke, Hugo von Hofmannsthal) and others in that line of descent, notably Beckett and Wallace Stevens … The Singularities, Banville’s exhilarating new novel, offers itself quite overtly as a rumination on, or rummage around, ideas about representation. Like much of his best work, it aims to both scrutinize and confront one of the central challenges of the human endeavor: how to create an accurate portrait of things … Banville is taking advantage of the breakthrough posited in The Infinities to create a universe inhabited by virtually all of his creations. But this isn’t merely a conceit or addendum along the lines of Paul Auster’s Travels in the Scriptorium. Banville has found a form that mobilizes his most cherished theme—the slipperiness of reality.”

–Leo Robson on John Banville’s The Singularities (The New York Times Book Review)

“Teddy lived long enough for his flaws to be fully exposed. All are laid bare in this book—the drinking, the infidelity, the selfishness, the casual cruelty, the emotional isolation. The central riddle of Kennedy is how these weaknesses existed alongside the benevolence, loyalty, perseverance and wisdom that made him one of the most influential senators in modern American history … More than just a personal profile, Farrell’s book revisits the origins of policy debates that still divide the country … Farrell mined historical archives from North Carolina to Kansas to California and many points in between. The result of his research is nearly 600 pages—not counting an extensive index and collection of source notes—that burst with detail … Farrell manages to unearth new tidbits about one of the most scrutinized lives in American politics.”

–Chris Megerian on John A. Farrell’s Ted Kennedy: A Life (The Los Angeles Times)

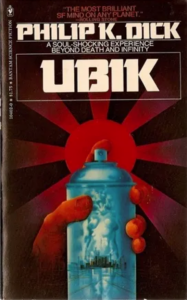

“The K stands for ‘Kindred.’ It was a family name, but if there’s anyone who can forgive a fanciful imputation of significance, it is Philip K. Dick. How lovely that a poet of alienation would come into existence bearing that word … The best of his work is fueled by nuclear-strength imagination, grand metaphysical and theological explorations, and prescience in matters of technology, marketing, consumerism, media and ecological catastrophe. Dick picked up on sinister cultural undercurrents the way a cat senses a can of tuna being opened six rooms away … The novel’s themes of entropy and delusion will swirl in your subconscious like a malevolent cone of soft serve. If I could propose two essential qualities of Dick as a human, they would be cosmic bafflement and heroic hopefulness, both present in Ubik. This is a novel with a long half-life. You may not clock the full effects until you find yourself thinking about it six or 60 months later.”

–Molly Young on the novels of Philip K. Dick (The New York Times)

“Equal parts hilarious and heartbreaking, this is the story of an irrepressible boy nobody wants, but readers will love … Demon is right about America’s condescending derision, but he’s wrong about his own worth. In a feat of literary alchemy, Kingsolver uses the fire of that boy’s spirit to illuminate—and singe—the darkest recesses of our country … Kingsolver hasn’t merely reclothed Dickens’s characters in modern dress and resettled them in southern Appalachia, the way some desperate Shakespeare director might reimagine A Midsummer Night’s Dream taking place in an Ikea. No, Kingsolver has reconceived the story in the fabric of contemporary life. Demon Copperhead is entirely her own thrilling story, a fierce examination of contemporary poverty and drug addiction tucked away in the richest country on Earth … Kingsolver has effectively reignited the moral indignation of the great Victorian novelist to dramatize the horrors of child poverty in the late 20th century … she’s raised the bar even higher, providing her best demonstration yet of a novel’s ability to simultaneously entertain and move and plead for reform.”

–Ron Charles on Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead (The Washington Post)

George Saunders’ Liberation Day, Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, and Paul Newman’s The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Week.

1. Liberation Day by George Saunders

(Random House)

12 Rave • 3 Positive • 2 Mixed

Read George Saunders on reading chaotically and the power of generous teachers, here

“Acutely relevant … Let’s bask in this new collection of short stories, which is how many of us first discovered him and where he excels like no other … Saunders’ imaginative capacity is on full display … Liberation Day carries echoes of Saunders’ previous work, but the ideas in this collection are more complex and nuanced, perhaps reflecting the new complexities of this brave new world of ours. The title story is only one of a handful of the nine stories in this collection that show us our collective and personal dilemmas, but in reading the problems so expressed—with compassion and humanity—our spirits are raised and perhaps healed. Part of the Saunders elixir is that we feel more empathetic after reading his work.”

–Scott Laughlin (The San Francisco Chronicle)

2. Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

(Harper)

9 Rave • 3 Positive • 3 Mixed • 1 Pan

“Kingsolver’s capacious, ingenious, wrenching, and funny survivor’s tale is a virtuoso present-day variation on Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, and she revels in creating wicked and sensitive character variations, dramatic trials-by-fire, and resounding social critiques, all told from Damon’s frank and piercing point of view in vibrantly inventive language. Every detail stings or sings as he reflects on nature, Appalachia, family, responsibility, love, and endemic social injustice. Kingsolver’s tour de force is a serpentine, hard-striking tale of profound dimension and resonance.”

–Donna Seaman (Booklist)

3. Signal Fires by Dani Shapiro

(Knopf)

4 Rave • 3 Positive

“How the accident happens (vividly detailed and choreographed by Shapiro) and how it is handled (never to be spoken of again) will haunt the survivors, and those pulled into the accident’s orbit, for the rest of the book … She is obviously interested in what people fail to say in Signal Fires, but the novel explores so much more—big picture stuff, like time and how it’s experienced … The author is adept, however, at juxtaposing the magical (not magical realism) and the modern, showing how locations can be the same and not the same, and that a place can be right for some and not for others but that life can still turn out all right … Shapiro goes deep in but it pays off. Her crisp prose propels the reader onward: I wanted to know what was going to happen to the characters and I was simultaneously fascinated by the metaphysics. It’s definitely a novel worth your time—whatever your sense of that is.”

–Maren Longbella (The Star Tribune)

**

1. The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World by Jonathan Freedland

(Harper)

11 Rave • 1 Positive

“Compelling … We know about Auschwitz. We know what happened there. But Freedland, with his strong, clear prose and vivid details, makes us feel it, and the first half of this book is not an easy read. The chillingly efficient mass murder of thousands of people is harrowing enough, but Freedland tells us stories of individual evils as well that are almost harder to take … His matter-of-fact tone makes it bearable for us to continue to read … The Escape Artist is riveting history, eloquently written and scrupulously researched. Rosenberg’s brilliance, courage and fortitude are nothing short of amazing.”

–Laurie Hertzel (The Star Tribune)

2. The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man by Paul Newman

(Knopf)

5 Rave • 5 Positive • 2 Mixed

“Newman at his best … The end product…is twice the book one could have dared to hope for, a narrative that is astute, introspective and surprisingly graceful … When we meet our heroes on the page, we want them to have something thoughtful to say—to make good on the admiration their outsize performances have won. Newman always seemed likely to pass that test, with his self-aware persona, storied marriage and generous charitable activities. Still, to see it come true in this rich book somehow imbues his characters’ pain and joy with fresh technicolor.”

–Michael O’Donnell (The Wall Street Journal)

3. Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad by Matthew F. Delmont

(Viking)

7 Rave

“A running theme in Delmont’s book—the prescience with which Black Americans identified the fascist threat while much of the United States was still in an isolationist mood … Delmont is an energetic storyteller, giving a vibrant sense of his subject in all of its dimensions. He draws attention to the role played by Black personnel in logistics … Delmont doesn’t skimp on…sobering stories, explaining that he wants to provide a ‘definitive history.’ But he also clearly sees his book as a chance to honor those Black Americans who fought for the United States but never properly got their due.”

–Jennifer Szalai (The New York Times)

Our smorgasbord of superior reviews this week includes John Jeremiah Sullivan on Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger, Bruce Handy on Paul Newman’s The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man, Ann Manov on John Boyne’s All the Broken Places, Colin Barrett on George Saunders’ Liberation Day, and Sigrid Nunez on Annie Ernaux’s Getting Lost.

“The experience of reading Cormac McCarthy’s new novel, The Passenger—alongside its twisted sister, Stella Maris, which comes out later this year—kept making me think about the word ‘portentous.’ Not finding this word identified as a Janus anywhere, I hereby nominate it for candidacy. ‘Portentous,’ according to Webster’s, can mean foreboding, ‘eliciting amazement’ and ‘being a grave or serious matter.’ But it can also mean ‘self-consciously solemn’ and ‘ponderously excessive.’ It contains its own yin-yang of success and failure. Applied to prose, it can mean that a writer has attained a genuinely prophetic, doom-laden gravitas, or that the writing goes after those very qualities and doesn’t get there, winding up pretentious. McCarthy has always been willing to balance on this fence. There is bravery involved, especially at heights of style where the difference can be between greatness and straight badness. He teeters more in these new books than in the several novels for which he is judged a great American writer … Much of The Passenger happens in a room, or a couple of rooms, where the same scene, with variations, runs on a loop. I suspect that many readers will resist or resent spending as much time there as we do. I came to find the goings-on sometimes captivating, but almost feel that I am covering for my abuser in confessing that … The Passenger is far from McCarthy’s finest work, but that’s because he has had the nerve to push himself into new places, at the age of all-but-90. He has tried something in these novels that he’d never done before: I don’t mean writing a woman (although there’s that), but writing normal people. Granted, these normal people are achingly good-looking and some of the smartest people in the world and they speak in lines, but they are not mythic. Or they are mythic but not entirely so.”

–John Jeremiah Sullivan on Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger (The New York Times Book Review)

“An odd duck of a book—welcome, but odd … Is The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man merely a supplement to The Last Movie Stars? For readers who have watched the series, the book can’t help but suffer in comparison for not being able to include glorious clip after glorious clip of Newman in action across his lengthy filmography … The memoir is necessarily incomplete, even speculative—a found object of sorts that has been carefully shaded and massaged into a facsimile of what Newman might have intended if he hadn’t turned his back on the whole thing. However grateful one is to have it—and it’s not pretending to be a smoothly polished work—it’s a bit of a Frankenstein’s monster … Don’t let that scare you: there is much to cherish here. The book is in Newman’s voice, with occasional interjections from the interviews with Woodward and others. It’s a familiar voice: genial but shrewd, self-deprecating but resolute … Emotionally cohesive and moving … Some passages, such as Newman’s account of his mother’s smothering but narcissistic love, have the quality of revelation turned rote … Don’t let that scare you, either. Some tidbits of decent gossip have managed to lodge between these covers.”

–Bruce Handy on Paul Newman’s The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man (AirMail)

“With his latest treacly tome All the Broken Places—complete with title so maudlin it preempts all mockery—Boyne has gifted us with a Holocaust novel so self-indulgent, so grossly stereotyped, so shameless and insipid that one is almost astonished that he has dared … This is not literature. As a grown-up sequel to children’s trash, All the Broken Places serves two roles. First, to demonstrate that Boyne definitely did not think that the Germans were innocent, definitely knew they were ‘complicit’ and ‘guilty’ and that history is ‘complicated,’ etc, thanks very much. Second, to serve as a sort of fan fiction for those peculiar adults who long for the comfort of a childhood favorite. As to this first goal, at least, it is a consummate failure, a wildly simplified narrative that misrepresents the extent of Nazi ideology. As in The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, Boyne underestimates the family’s awareness of the Holocaust, lending his German characters an exaggerated naivety, or implausible deniability … Boyne flaunts a teenager’s understanding of the causes and consequences of the Second World War … As with so much Holocaust fiction All the Broken Places utterly fails in its stated purpose: making the next generation slightly less likely to participate in the next genocide…Boyne’s reduction of Nazi ideology to a fringe belief, expressed in infrequent outbursts—’those filthy Jews’—is all the more absurd now that he’s writing for grown-ups … We don’t need anyone to teach us how to recognize the barefaced devil; the danger is the insidious and gradual creep of violence into the civilised and everyday. This is what the philosopher Theodor Adorno’s dictum—’To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’—warned of: art unable to recognise the break the Holocaust represented with the past, afraid to apprehend the failure of the civilising project. With this childish drivel in which the villains and victims come labelled and sorted, Boyne yet again seems immune to its lessons.”

–Ann Manov on John Boyne’s All the Broken Places (The New Statesman)

“… it seems that nearly a decade later, Saunders is no longer so sure about the possibility of transformative heroism or resistance, or what that might even mean. The prevailing mood throughout is much more muted and uncertain, with a concomitant diminution in linguistic vivacity. The language the characters speak and think in is flatter, deader, at once more anodyne and anguished … Saunders has tasked himself with treading a fine line in these stories: How to depict the incapacitating malaise of despair without succumbing to it? He does not always completely succeed … Here, as in one or two other stories, it feels as if the setup and the characters interest Saunders less than the opportunity to wallow in moral conundrums and impasses of conscience … a spiky, at times difficult collection, seldom providing the reader with much in the way of catharsis. But these are stories worth reading, the best of them as thought-provoking and resonant as a fan of Saunders might expect. Eschewing the speculatively richer, more dramatic question of what happens after the system comes crashing down, Saunders focuses instead on the queasy, knotty consequences of our present dilemma: What if it doesn’t?”

–Colin Barrett on George Saunders’ Liberation Day (The New York Times Book Review)

“The journal is relentless in its presentation of her pain and abasement, but no less so in its effort to dissect what just happened. Here is the same deep probing for truth, the same fanatical quest for self-awareness to be found in all Ernaux’s work. Though she sleeps poorly and often wakes exhausted, she struggles to remember and write down her dreams—many of them nightmares—and to interpret them. She resists any attempt to do what most people (and a million pop songs) would advise her to do, put the heartbreak behind and move on, but rather fixates on it. She must: she believes that only through understanding what happened will she be able to endure it, and that only by putting it down on paper can she hope to understand. For her, this is precisely what writing—self-narrative, specifically—is for … Like most diaries—and quite unlike Ernaux’s usual meticulously concise prose—Getting Lost contains its share of banalities, messy thoughts, inconsistencies, and unpolished sentences. It is often repetitious, and accounts of Ernaux’s dreams are no more exciting to hear about than anyone else’s ever are. But, to echo James Wood’s observation about reading Karl Ove Knausgaard—another writer consumed with his own intimate history—even when I was bored I was interested … as a matador-writer Ernaux has always faced the bull’s horns. She is a master of close and graceful capework, and, as in any bullfight, it is the show of courage before danger and possible disaster that enthralls the spectator.”

–Sigrid Nunez on Annie Ernaux’s Getting Lost (The New York Review of Books)

Leonard Cohen’s A Ballet of Lepers, Lydia Millet’s Dinosaurs, and Andrew Miller’s The Slowworm’s Song all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Week.

*

1. The Slowworm’s Song by Andrew Miller

(Europa Editions)

7 Rave • 4 Positive • 4 Mixed

“Bolder and more exquisitely menacing than anything he’s done before … A peculiarly moving account of casual youthful error, and of the hell that such errors can send us to … Miller delineates the details of life in an urban barracks … He conjures the fear and the confusion of being out on patrol … So, what happened in Belfast? What did Stephen do? The revelation, when it comes, is unsensational: a pitiful, inadvertent atrocity, and all the more shocking for that … At the level of the sentence, the writing is near perfect. But the novel’s excellence goes far beyond this. There’s a depth and a sweetness, a gravity, to Stephen’s simplest observations … Miller’s last novel didn’t make the Booker list, but this restrained, beautifully written apologia for our common frailty surely should.”

–Elizabeth Lowry (The Guardian)

2. Dinosaurs by Lydia Millet

(W. W. Norton & Company)

6 Rave • 5 Positive • 3 Mixed

Read an interview with Lydia Millet here

“Lydia Millet’s magnificent new novel, Dinosaurs, highlights our shortcomings in terms of how we treat each other and our environment, and subtly seeks to draw some lessons from the natural world … Millet rel[ies] on spare prose that is dense with meaning if the reader wants to think deeper, but otherwise feels simply like edifying naturalist interludes. Her observations about human behavior are astute … Millet writes with a dexterous rhythm and she has a natural ear for lived-in dialogue … Time after time, Dinosaurs develops in unexpected directions, avoiding several potentially cliched turns and any sort of moralizing messaging. The novel buzzes with an uneasy undercurrent of violence.”

–Cory Oldweiler (The Boston Globe)

3. A Ballet of Lepers by Leonard Cohen

(Grove)

2 Rave • 3 Positive • 3 Mixed

“The already mature persona of Cohen’s early songs suggests a youth of burning intensity, wandering by moonlight amid gothic architecture, contemplating the spilled blood of his ancestors, touching perfect bodies with his mind, and so forth. On that score A Ballet of Lepersoffers ample confirmation … There is much existential brooding, which yields Cohen’s best writing. The action is somewhat less scintillating … Overall the novel leaves the impression of a young man imagining his way into the rages of older men he doesn’t yet fathom … There are moments of bracing sexual frankness, a few indelible images of savagery, and spare doses of potent humor.”

–Christian Lorentzen (The Telegraph)

**

1. Nerd: Adventures in Fandom from This Universe to the Multiverse by Maya Phillips

(Atria)

3 Rave • 1 Positive

Read Maya Phillips on the the responsibility of Black superheroes here

“In her debut essay collection…fandom is an expansive, transformative source of self-enlightenment … As a fan and a professional critic, Phillips sees the value in pop culture’s ability to speak deeper truths, however uncomfortable, about society. Navigating pop culture as a Black fan can be a frustrating exercise in otherness, she writes, but fandom can also be a conscious act of reclamation … Nerd spans decades of pop culture, smoothly weaving multiple interconnected webs. Phillips indulges in her obsessions, but she’s never afraid to critique and deconstruct. In this engaging compendium of cultural criticism, Phillips successfully proves that the complex discipline of fandom is a valuable piece of humanity’s flawed but hopeful history.”

–Vanessa Willoughby (BookPage)

2. Bold Ventures: Thirteen Tales of Architectural Tragedy by Charlotte Van den Broeck

(Other Press)

2 Rave • 2 Positive • 1 Mixed

Read an excerpt from Bold Ventures here

“Beguiling … The author can stubbornly cling to her thesis, morbidly romanticizing like that goth friend in high school with a penchant for the Cure … I have no idea where this book, translated gracefully from the Dutch by David McKay, will land in the Dewey Decimal System. The suicidal-architect conceit turns out to be something of a facade for a blend of memoir, travelogue and philosophical tract … A strain of rumination runs through all her investigations … In our moment of ‘quiet quitting,’ resistance to corporate domination and a conviction that capitalism is in decay, Bold Ventures does arrive as a timely interrogation of what, exactly, constitutes success—of how to live … Her tiered confection is a small marvel: a monument to human beings continuing to reach for the skies, even after their plans dissolve in dust.”

–Alexandra Jacobs (The New York Times)

3. A Horse at Night by Amina Cain

(Dorothy)

1 Rave • 3 Positive

“Fragments of moving image, performance art, paintings, etchings, and prints materialize and dissipate, and a dialogue between these impressions opens up like a portal of ambiences, coming into focus yet remaining out of grasp … In some ways this book functions as a gallery of interiority, deep and fluctuating with nebular dispositions and impulses. It is an effort towards articulating the intangible … a transmutation of fiction and nonfiction, a form of unfurling, soft and grainy at the edges. Moving through this text feels like resting your eyes on shifting shapes on a walk in the dusk.”

–Sophie Brown (Astra)

Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes Katy Waldman on Lydia Millet’s Dinosaurs, Nathan Goldman on Leonard Cohen’s A Ballet of Lepers, Sophie Gilbert on Rina Raphael’s The Gospel of Wellness, Caoilinn Hughes on Andrew Miller’s The Slowworm’s Song, and Jay Caspian Kang on Anders Monson’s Predator.

“Millet is energized…by how feelings are ‘intermeshed with abstract thought,’ with ‘our place in the wider landscape.’ Why, her work demands, are we afraid to die? What are the ethics of wanting what we want? … If both fiction and people are blinkered, self-stunned, perhaps they require a similar intervention. Millet, eschewing the arc of the private individual, also forgoes the novel’s traditional shape, in which tensions build to a climax. Her method is to churn up themes, generating a kind of mental weather, as if a book were less a trajectory than an atmosphere … Like Joy Williams, Millet uses fiction to elegize the collapsing biosphere. Also like Williams, she has a raunchy, fanged wit, often aimed at human self-delusion. Unlike Williams, though, Millet never lets surrealism darken into delirium, and her misanthropy feels circumstantial, not cosmic … In Dinosaurs, Millet transposes her signal motifs into a gentler key. The book’s large-scale catastrophe is only as obvious as our own—which is to say, ecological ruin lurks in the background, but the story clings to characters’ muted, often deliberately stifled lives … Potted summaries of Millet have a way of risking slander. Like A Children’s Bible, Dinosaurs is sharp and implacably funny; it evades the sanctimony you’d expect … Dinosaurs thus belongs to a cadre of recent novels that wrestle with the phenomenon of complex loss: grief that lingers after incomplete or ambiguous endings … evolution is only ever a possibility, never a sure thing. The novel is both aubade and vesper. It implies that some people can’t escape the prisons of who they are.”

–Katy Waldman on Lydia Millet’s Dinosaurs (The New Yorker)

“A grim fable … While the novel is stirring in its almost mythological simplicity, compelling in its portrait of deranged rapture, intelligently attuned to the seductions and self-delusions of false transcendence, it is also structurally clumsy, hindered by a climactic twist and mechanically staged stock characters … These same flaws afflict…the short fiction collected in A Ballet of Lepers. But unlike the early novel, many of these stories are built around striking images of frailty and desire … In his lyrics, Cohen took the melodrama and solipsism that plagued his prose and alchemized them into something more moving and mysterious. Once he turned to songwriting, Cohen set fiction aside. Perhaps it was a purely strategic decision, or maybe he ultimately understood that it was not his form. If the pieces gathered in A Ballet of Lepers testify to this, they nonetheless offer nascent glimmers of his inimitable artistic vision: intimate yet aloof, trembling with weakness even as it aches toward wisdom.”

–Nathan Goldman on Leonard Cohen’s A Ballet of Lepers (The New York Times Book Review)

“The more overwhelmed and exhausted we get, the more we seemingly owe it to ourselves to pursue ‘wellness.’ The more burdens we accumulate—children, aging parents, student loans, mortgages, anxiety disorders, bad backs, extra pounds—the more we’re urged to be well by way of still more effort: throwing out our plastic containers, cutting out lectins, practicing mindfulness, learning about environmental toxins, doing the research … Somewhere along the way, though, the thing that was supposed to help us heal ourselves became yet another obligation. And the stresses of the coronavirus pandemic only exacerbated what was already happening—the slow, immensely lucrative poisoning of something supposed to be a cure … Virtually anything can be curative if you think about it creatively enough, which is in part the quandary. ‘We have become a self-care nation,’ Raphael writes, ‘though arguably one that still lacks the fundamentals of well-being.’ The Gospel of Wellness argues that the industry has mushroomed in such a way because it’s filling a void that many people, and especially women, feel … Wellness puts the onus on the consumer to make up for everything modern society can’t or won’t provide; it extends the illusion of control … Modern wellness, at its core, is a self-sustaining doom loop of precautionary, aspirational consumption: Buy to be better to buy more to be better still. Which is why, despite Raphael’s arguments, I don’t fully buy that wellness has taken on the role of religion. Instead, in classically entrepreneurial American fashion, it’s become extra unpaid work—the very thing we don’t need more of and truly don’t have time for.”

–Sophie Gilbert on Rina Raphael’s The Gospel of Wellness: Gyms, Gurus, Goop, and the False Promise of Self-Care (The Atlantic)

“Miller’s novel subtly and morosely explores the crisis of Englishness that ties together events of the 20th century with those of the 21st: the colonial anxieties of the Troubles and the self-sabotage of Brexit, which was brought to pass, at best, by protest vote, and at worst, with racist motives or a macho-imperial sense of entitlement. The ironies of Rose’s shortcomings—the failure to reconcile his own ideology, how his account offers no dialogue and centers his own voice, how he tasks his daughter with being his reason to live while telling others that ‘she owes me nothing—make this book not only nuanced and affecting but historiographical. It reads truer than memoir…. As a device, the letter is problematic, especially when Rose details events and conversations his daughter was present for (and when he describes sex stains he and her mother left on the carpet). Another problem is that Rose…writes like a novelist, albeit one I am recommending … But the unbroken personal account gives us access to a beautifully fraught psyche … His story becomes a state-of-the-nation novel, in elegiac prose.”

–Caoilinn Hughes on Andrew Miller’s The Slowworm’s Song (The New York Times Book Review)

“This is a risky, almost preposterous literary gambit. Monson presents himself in a fully earnest fashion, rips open his heart to expose all his flaws, and then asks you to care deeply about what is clearly a doomed and ultimately insignificant crisis. The book’s emotional eddies and nostalgic reveries add up to a trite point about media, masculinity, and violence, and still Monson is only partially willing to implicate himself in what he observes, repeatedly reminding us, for instance, that he feels appalled by the January 6th rioters. Reading Predator sometimes felt like reading a tweet thread from the most annoying white people on Twitter—the type who feel the need to very loudly condemn and apologize for their backward brethren. And yet, against all odds, Monson pulls this off. Predator is not a pleasant read, but its moral oscillations and reveries fully capture white guilt in its most cringeworthy form. This, at least in my reading, is intentional … Monson does not have a fixed relationship with this violence. He condemns it but he does not dismiss it, nor does he really believe that he has expunged it fully from himself … Problematic-male confessors, it turns out, are always talking to one another…When I was in my late twenties, I wrote a novel about a down-and-out Korean American man living in San Francisco who was obsessed with the Virginia Tech massacre. (The title came from a song by Silver Jews, a band that Monson quotes in Predator.) The point wasn’t to theorize something about toxic masculinity, or even to get people to understand where I was coming from. The desire was more formal in nature: how do you craft sentences that reflect you at your most depraved? Can the sequence of words you write on the page make the reader love you, despite everything you’re telling him about yourself? I am not sure if I succeeded in that task, but Monson, by spooling out the neuroses of the once violent, but now domesticated liberal man…and never shying away from his own lameness, certainly has.”

–Jay Caspian Kang on Anders Monson’s Predator: A Memoir, a Movie, an Obsession (The New Yorker)

Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts, Annie Ernaux’s Getting Lost, Elizabeth McCracken’s The Hero of This Book, and Orhan Pamuk’s Nights of Plague all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Week.

*

1. Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng

(Penguin Press)

14 Rave • 2 Positive • 2 Mixed

Listen to an interview with Celeste Ng here

“Stunning … One of Ng’s most poignant tricks in this novel is to bury its central tragedy…in the middle of the action. This raises the narrative from the specific story of a confused boy and his defeated father to a reflection on the universal bond between parents and children … Our Missing Hearts will land differently for individual readers. One element we shouldn’t miss is Ng’s bold reversal of the biblical story of the Tower of Babel. It is the drive for conformity, the suppression of our glorious cacophony, that will doom us. And it is the expression of individual souls that will save us.”

–Bethanne Patrick (The Los Angeles Times)

2. The Hero of This Book by Elizabeth McCracken

(Ecco)

11 Rave • 3 Positive

Listen to an interview with Elizabeth McCracken here

“… soulful, melancholy … McCracken deftly evokes how so many of us feel about our mothers: that they are just there, and always there, and that any intimation that they were not always there or weren’t ever just as they are is an affront to the primacy of their connection to their child. Many children will never forget the moment they realized that their mother was a separate human being, who made mistakes and had faults and foibles all their own, separate from their own selves. This existential shock reverberates throughout McCracken’s book, coupled with the shock of that mother no longer being there … In this vivid composition, McCracken paints the final layer of the portrait of the mother she has so painstakingly drawn in the preceding pages … ‘Don’t trust a writer who gives out advice,’ McCracken warns in the first chapter. But the irony is, her words create an exquisite alchemy that makes a reader ready to follow her anywhere, believe every word she writes down. Is this book a novel or is it a memoir? It matters not at all. With every vital, potent sentence, McCracken conveys the electric and primal nature of that first fundamental love.”

–Janice Y.K. Lee (The New York Times Book Review)

3. Nights of Plague by Orhan Pamuk

(Knopf)

3 Rave • 7 Positive • 2 Mixed

“… fascinating, wearying, and, dare I say, oddly timeless book, although Pamuk clearly has an eye on the present … a complex and intriguing amalgam of form and genre. Some passages read like a textbook, others like a murder mystery … At times, Nights of Plague reads like the work of someone who fell down the well of their own research and imagination, lost to an excess of details, characters, and events. While I do not know Turkish, and am always slightly wary of translations, the prose itself can feel ploddingly academic, clotted with events as if this were truly an exercise in historical documentation … Elsewhere, there are gorgeous passages of description, surprising moments of lightness, narrative sections full of drama and old-fashioned cliff-hangers, and memorable sentences throughout … Mostly, I was enthralled by the ways in which the islanders’ crimes, misdemeanors, and fatal missteps mirror those committed during our current worldwide coronavirus and political meltdowns … Masterfully imagined and relentlessly inventive, Nights of Plague is worthy of the time a prepared reader will need to invest in it. Although it sometimes feels a little homework-y, that can be a virtue, too, encouraging one to rethink the present and bone up on Ottoman history simultaneously. Indeed, asking much of the reader is in keeping with Pamuk’s impressive, multifaceted, and swaggering intentions.”

–Helen Schulman (AirMail)

**

1. Breathless: The Scientific Race to Defeat a Deadly Virus by David Quammen

(Simon & Schuster)

6 Rave

Read an excerpt from Breathless here

“Compelling and terrifying … Breathless is so good that I was slow to realize that it lacks the vivid you-are-there details of Spillover. That’s because he wasn’t there … A different species of tour de force … These barriers didn’t prevent him from writing a luminous, passionate account of the defining crisis of our time—and the unprecedented international response to it … Quammen marries an old-fashioned love of colorful language to his passion for detail—an odd coupling that results not just in a lucid book about an important topic, but also in a book that’s a pleasure to read.”

–Michael Sims (The New York Times Book Review)

2. American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis by Adam Hochschild

(Mariner)

5 Rave • 1 Positive

“A story worth telling, and in American Midnight, the historian Adam Hochschild…recounts it with verve and insight … This is, to be sure, history with a purpose, not a search for a ‘usable history’ that seeks a past that provides comfort and moral elevation for the present. The purpose here is prevention … In examining this forgotten hiccough in the country’s history, we encounter several unforgettable figures who come to life on these pages … This book is, above all, a chronicle of dissent in a democracy, setting forth in vivid languages the abuses and extremes that characterized the period during and shortly after the great crusade … Much of what Hochschild examines in this volume will be news to his readers. It is, ultimately, news we all can use.”

–David M. Shribman (The Boston Globe)

3. Getting Lost by Annie Ernaux

(Seven Stories Press)

5 Rave • 1 Positive • 1 Pan

Read an excerpt from Getting Lost here

“The sex is torrid, and described with a lemony eye for detail … The almost primitive directness of her voice is bracing. It’s as if she’s carving each sentence onto the surface of a table with a knife. She is, in her writing, definitely not the sort of girl whose bicycle has a basket … Not tweaked in postproduction … The bedroom scenes are bulldozing … This book is an anthology of her projected anxieties. Her heart is some sort of nocturnal beast … Getting Lost is a feverish book. It’s about being impaled by desire, and about the things human beings want, as opposed to the things for which they settle. Is it a major book? Probably not. But it’s one of those books about loneliness that, on every page, makes you feel less alone.”

–Dwight Garner (The New York Times)

Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Alexander Chee on Seán Hewitt’s All Down Darkness Wide, Jonathan Lee on William Boyd’s The Romantic, Leslie Jamison on Nastassja Martin’s In the Eye of the Wild, Jamie Hood on Annie Ernaux’s Getting Lost, and Joe Klein on Maggie Haberman’s Confidence Man.

“In some of the most beautiful prose I’ve read in years, Hewitt remembers cruising with his heart in his throat, keeping one eye on the living men moving in and out of the shadows while being aware that he is surrounded by the dead … the two lovers serve another purpose for Hewitt: They are mirrors for something unsettling he recognizes in himself, something he can no longer ignore. This intensely original memoir’s real subject is what appears to Hewitt, in the aftermath of these relationships, as a thread that connects these men to each other, and to himself—’a sort of curse, a brokenness in them, in us’ … Over the course of the memoir, Hewitt realizes that his upbringing and surroundings have forced him to hide his true self—his class background, his desire for the sort of sexual community he found cruising around the graveyard—and that doing so has taken a toll. But he also realizes how the same might be true for Jack, for Elias, and for all those men he sensed around him in the dark … His desire for inviolability is also the desire to become part of the white-male ruling class—complicated by the knowledge that, if he were to be exposed as gay, all the efforts he’d made to hide his lower-class upbringing would be worth nothing.”

–Alexander Chee on Seán Hewitt’s All Down Darkness Wide (The Atlantic)

“…what is often lost behind the sheer pleasure brought by his books is their layered Chekhovian subtleties: Boyd is abundantly talented at capturing life’s disconnections, in prose that provides no easy consolations. This may be why the ‘whole life’ novel, exemplified by Any Human Heart, occupies such a special place in his body of work, and why it is satisfying to see him return to this cradle-to-grave territory. For all the hijinks that keep us turning his pages, Boyd is ultimately an artist of diminishment—one who tracks, in The Romantic, the ways in which a seemingly ‘great’ life, lived over an entire century, can still dwindle, inexorably, into almost nothing … It is hard to think of another contemporary author who quietly marches his readers so relentlessly towards death … One of the many pleasures of Boyd’s fiction is that history doesn’t just happen around his characters—it happens to them … It is intoxicating to be in the company of a writer who seems to be having such fun peeling away the skin of history and inserting his characters underneath. Like a fine taxidermist, Boyd’s craft creates such amusingly hyperreal results that you can sometimes forget what a grim business it is.”

–Jonathan Lee on William Boyd’s The Romantic (The Guardian)

“Throughout her memoir, In the Eye of the Wild, Martin never calls this encounter an attack. Instead, she describes it as a meeting, an implosion of boundaries, a melding of forms, and, most notably, ‘the bear’s kiss’…Her word ‘kiss’ is both emotionally subversive—almost erotic—and also insistently physical … In the Eye of the Wild is a book about translation—the desire to translate trauma into meaning, or animal consciousness into legible interior life—and Sophie R. Lewis’s translation from French into English preserves the quicksilver nature of Martin’s voice as it flickers between droll understatement, furious indignation, reverential incantation, and wry humor. (She relishes telling a man pushing her wheelchair through a Moscow hospital, ‘I had a fight with a bear.’) This is also a book about tonal metamorphosis: no single, static affect—mournful, deadpan, awestruck—could suffice … Martin acknowledges that her own impulses toward ‘building connections, analyzing and dissecting, fashioning a survivor’s castles in the air’ are also coping mechanisms for surviving her trauma, and she seems acutely aware of the potential skepticism of her readers, who might wonder what delusions are at work when a person describes her gruesome mauling as a kiss. But she remains committed to understanding her attack as an experience of transformation rather than destruction … Martin is asking us to believe in beasts—not to project our human explanations onto their behaviors or write them off as terminally opaque, but instead to embrace uncomfortable models of communion. What can we learn, Martin asks, when the familiar boundaries between humans and animals collapse?”

–Leslie Jamison on Nastassja Martin’s In the Eye of the Wild (The New York Review of Books)

“To read Ernaux often feels this way: in her exhaustive reckonings with her own life, one finds a search for lost time that exposes the unstable bounds and incoherencies of meaning in our own narratives of its passing. In a moment, as Ernaux has written, when technology and socio-digital media have rendered the ‘obscurity of previous centuries’ obsolete and made it so that those of us still living are beginning to be ‘resurrected ahead of time,’ her meticulous campaign of recording a ‘total novel’ of life imagines narrative beyond the vicissitudes of temporality, deliberately attendant to the unreliable, stuttering nature of remembrance. Ernaux imparts on her reader a sense that memory, like any other knowledge system, is an infinitely changeable field, one given astonishing density by, but not reducible to, the individual experience … This is the disarming closeness one encounters when brushing up against her work. Though oriented through the needle’s eye of her particular world, her nearly sociological sensibility and investment in generating collective feeling dress her accounts of one woman’s life in uncanny familiarity … The scope of Getting Lost is narrow, utterly transfixed by events of an intimate order. These intimacies become a kind of mythos, hyper-saturated, as if passion were being presented to Ernaux in Technicolor for the very first time … From these humble beginnings, then, Ernaux’s unabashed delight in her own corporeality and the decadent descriptions of her pleasure in Getting Lost appear as insurgent thrills … That we again face an era when the gains of feminist and sexual liberationist movements are being reactionarily regressed, Ernaux’s erotic manifesto—and her radical exhortation of the value of foregrounding women’s personal narratives in a public and political context—has perhaps never been more essential in relation to ongoing demands for bodily integrity and autonomy.”

–Jamie Hood on Annie Ernaux’s Getting Lost (The Baffler)

“Donald Trump is too much with us. We are stalled, rubbernecking the endless carnage of his road rage. There have been far too many books about him, with far too many ‘revelations.’ After a while, the revelations melt into an indistinguishable muck; his boorish narcissism, a bludgeon. And so it’s hard to assess the news value of Confidence Man … No doubt, there are revelations aplenty here. But this is a book more notable for the quality of its observations about Trump’s character than for its newsbreaks. It will be a primary source about the most vexing president in American history for years to come … [Haberman] is an exemplar of her craft, relentless, judicious and even-keeled, giving credit, where due, to her colleagues and fellow biographers, while admitting and adjusting her occasional mistakes … One of the many services Haberman performs in Confidence Man is to set out the process by which Trump came to his outrageous positions … Maggie Haberman has been there for it all. The story she tells is unbearably painful because Trump’s success is a reflection of our national failure to take ourselves seriously.”

–Joe Klein on Maggie Haberman’s Confidence Man: The Making of Donald Trump and the Breaking of America (The New York Times Book Review)

The hits just keep coming: As autumn descends with blessedly cooler temperatures and falling leaves, so too drop some excellent science fiction and fantasy books. We already sung the praises of Elijah Kinch Spector’s clever debut Kalyna the Soothsayer in August, but that’s moved to October, so be sure to add it to your TBR. Otherwise, there’s Saturnalia celebrations, Martian mathematics messages, and murder mysteries in spaaace. Plus, new works from comics legends like Alan Moore (in a short fiction collection) and Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples (with the return of their beloved comic book series Saga).

*

Station Eternity by Mur Lafferty

(Berkley Books, October 4)

This year’s SFF has had just the best hooks, with “Miss Marple on a space station” right up there. But because this is Mur Lafferty, who already won at the locked-room murder mystery with Six Wakes, she adds a snarky but necessary twist to the Marple influence: Imagine if people kept getting murdered around you, and you were something between a constant suspect and an amateur detective despite solving every single case. It would ruin any chance at a normal life with relationships and the ability to put down roots. So no surprise that Mallory Viridian turns herself into a pariah by escaping to space… but when a shuttle of humans prepares to dock at the sentient Station Eternity, Mal will have to draw upon her preternatural crime-solving ability once again.

Saga Volume 10 by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples

(Image Comics, October 5)

Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ expansive space opera series about star-crossed lovers turned surprise parents left us on the most devastating cliffhanger imaginable in 2018… and then a few things happened to utterly change our world. But Saga, which has been running since 2012, was only halfway through its planned run, so we knew it was only a matter of time before Hazel and her family (blood, found/chosen, ghosts, and otherwise) returned with the next chapter in her childhood. This latest volume collects all of the issues from 2022 (including the double-sized return issue from the start of the year), as Hazel’s exploration of magic, just like her impossible existence, yet again radically changes how her parents’ two warring races see the universe.

Saturnalia by Stephanie Feldman

(Unnamed Press, October 11)

I haven’t always been one for occult secret society stories because they can be almost too removed from reality, but Stephanie Feldman’s latest seems grounded in the relatable: Philadelphia’s Saturn Club is an elite social tier full of its own pecking-order bullshit, which is why Nina walked away from it three years ago. There’s also the fact that its annual celebration of Saturnalia, or the winter solstice (which has become as entrenched in American culture as Thanksgiving) is a holiday for ignoring the looming climate change, which feels very much like something our present world would do. But when Nina gets an enticing invite to don her blackest black dress and the anonymity of a mask to plunge back into that genteel underworld, of course she can’t resist. Because when you’re most ignoring the problem is when it’s also most likely to become a world-changing issue—and I’m willing to bet that the Saturn Club doesn’t just flirt with the occult, but may be harnessing some real powers on the solstice.

Illuminations: Stories by Alan Moore

(Bloomsbury Publishing, October 11)

At this year’s U.S. Book Show, Alan Moore described the short story as “the best form for any writer to start and presumably end their career with.” Big emphasis on presumably—the comics stalwart and novelist (Jerusalem) will soon be embarking on a five-novel fantasy series called Long London. But that’s not out til 2024, and in the meantime there’s Illuminations, a collection of nine pieces spanning forty years of Moore’s illustrious career. Certainly the biggest draw for Watchmen fans will be the novella “What We Can Know About Thunderman,” which bitingly retells comics history (through thinly veiled aliases) and examines the chasm between the original medium and the cinematic attempts at adaptation. But there are also shorts like “A Hypothetical Lizard,” which was adapted into a comic in 2007 but now is present in its original prose form. As you might have guessed from the collection’s title, each entry involves some level of illumination or realization, as processed through Moore’s wild imagination.

The Immortality Thief by Taran Hunt

(Solaris, October 11)

Though a certain fantasy series kind of cornered the market on the Philosopher’s Stone, it’s nice to be reminded that this mythical alchemical artifact has existed for centuries and that it can be used in other narrative contexts—like in Taran Hunt’s sci-fi adventure debut. This fast-paced space heist drops criminal (slash linguist slash refugee) Sean Wren into an abandoned ship on the edge of a dying star about to go supernova. Days away from being wiped out is a good ticking clock for a thief who must snatch a chance at immortality for the human Republic mounting a last stand against the ruling alien Ministers. Whether Wren’s talent for ancient languages will let him decipher the Philosopher’s Stone, while fending off the claustrophobic spaceship’s inhuman inhabitants, is another matter entirely.

Singer Distance by Ethan Chatagnier

(Tin House Books, October 18)

With TV series like For All Mankind and Mary Robinette Kowal’s Lady Astronaut books, there’s a rising subgenre of alternate history SF wondering how Earth’s relationship to space and other planets might have changed depending on various factors: a shift in the space race, a meteorite turning up the Doomsday Clock on our little planet… or if Mars started communicating with us. Such is the case in Ethan Chatagnier’s (Warnings from the Future) debut novel, set in a version of the 1960s where Earth has been communicating with Mars since 1894 via symbols carved (or burnt, or planted) into its surface. MIT genius Crystal Singer is the latest would-be messenger who thinks she has solved the Martians’ impossible math; but when she manages to start up the conversation again, her own disappearance prompts her boyfriend Rick and their hippie friends to ponder just how much distance is actually between Crystal and her fellow Earthlings.

Into the Riverlands by Nghi Vo

(Tordotcom Publishing, October 25)

Nghi Vo’s latest installment in the Singing Hills Cycle of novellas sees wandering cleric Chih, accompanied by their talking bird companion Almost Brilliant, recording the stories of the riverlands’ martial artists. But considering these legends’ near-immortal lifespans as well as differences in perspective and memory, Chih learns that there is no single story but rather various retellings—including concerning the adventures of Chih themself. The Singing Hills Cycle can be read in any order, but this seems the perfect entry point for new readers.

The Scratch Daughters by H. A. Clarke

(Erewhon Books, October 25)

My favorite way to describe August Clarke’s witchy 2020 banger The Scapegracers is that it’s got The Craft vibes but for readers like me who by dint of age or generation just happened to miss The Craft. (I’m much more of a Practical Magic gal.) It also doesn’t feel like it’s trying to capture that specific moment of 1990s cinematic history, but is hip to the times without pandering to Gen Z, or any generation, for that matter. It’s sharp, it’s queer, it’s techy, it’s spiky, it’s magical: Social outcast Sidways Pike found her unlikely coven in the cool girls and the incredible spells they conjured together, but now she’s back to being on her own. As she chases down the infuriatingly hot girl who stole her specter (a.k.a. what makes her a witch), Sideways may not be able to rely on anyone but Mr. Scratch, the inky book devil she’s let possess her. But a specter-less daughter of Scratch is her own force to be reckoned with.