1. We That Are Young by Preti Taneja

6 Rave • 3 Positive • 2 Mixed

“British academic and human rights activist Preti Taneja has packed her debut novel with so much insight and feeling for contemporary India that her sentences seem to spill out as if from an overstuffed bag. It’s a marvel that she was able to pack in so much (plot, atmosphere, social observation, you name it) while sustaining such propulsive energy over the course of nearly 500 pages, and yet she manages to the last. The overall effect is dizzying, dazzling, and ultimately convincing and immersive … Taneja captures her sprawling subject in language befitting such epic sweep. She stuffs her prose with metaphor and simile, which can be a bit much at times, but more often than not serves to ground this novel of big ideas in the physical world … Taneja proves that nothing more than feelings—particularly when wielded by demented oligarchs and their misguided children—have the power to bring the world crashing down.”

–Eugenia Williamson (The Boston Globe)

Read an essay by Preti Taneja here

*

2. French Exit by Patrick DeWitt

3 Rave • 7 Positive

“The opening scene of Patrick deWitt’s French Exit is so perfectly staged that a curtain seems to rise on his elegant creation … The reader too may be a little confused. This certainly does not seem like a Patrick deWitt novel … What’s more, these characters belong in a Noel Coward play … Within a few sentences, the comic brilliance that sparked deWitt’s earlier adventures ignites this ‘tragedy of manners’ … Wisecracks detonate throughout French Exit warding off sentimentality. Indeed, the novel is so mannered, so arch, that even intimate moments are barbed with slyly traded quips.”

–Anna Mundow (The Washington Post)

Read Patrick DeWitt on 5 Mid-Century Commonwealth Writers You Should Read

*

3. How Are You Going to Save Yourself by JM Holmes

5 Rave • 3 Positive

“The raucous, heartbreaking, bawdy tales in JM Holmes’s debut collection possess an assured lyricism, uncompromising in its interrogation of race, class, drugs and family … In the explosive opener … the story culminates in a moment so brutally honest, so quietly ferocious, it left me dazed … As with any collection, some stories are stronger than others. Holmes renders male characters with microscopic precision; the same level of nuance afforded to his female characters would have added even more depth … he is a distinctive writer … Spare in style, strikingly urgent, his is a voice to get excited about.”

–Irenosen Okojie (The Guardian)

*

4. Ohio by Stephen Markley

3 Rave • 5 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Markley’s debut is a sprawling, beautiful novel that explores the aftermath of the Great Recession … Markley intersperses the stories of the four Ohioans with flashbacks to high school, and his portrayals are horrifyingly accurate. He does a perfect job examining the casual cruelties teenagers inflict on one another … There’s a lot going on in Ohio—a sprawling cast of main and supporting characters, and a series of interconnected events that doesn’t come together until the book’s shocking conclusion. But Markley handles it beautifully; the novel is intricately constructed, with gorgeous, fiery writing that pulls the reader in and never lets go … Written with a real love for its characters, Ohio isn’t just a remarkable debut novel, it’s a wild, angry and devastating masterpiece of a book.”

–Michael Schaub (NPR)

*

5. Praise Song for the Butterflies by Bernice L. McFadden

3 Rave • 1 Positive

“Beautifully written and expertly structured, Praise Song for the Butterflies includes plenty of twists, such as surprises about Abeo’s lineage, as well as delicate explorations of the gray areas that surface for Abeo—and her family—when she returns to her former life. Abeo’s time in New York is particularly well-drawn, as McFadden doesn’t oversimplify the difficulties of recovery and demonstrates (particularly through Femi) the importance of patience, understanding and unconditional love. Perhaps one of the best books of the year, Praise Song for the Butterflies is a stunning, brief portrait that humanizes the plight of those in ritual servitude. It’s a fantastic work from a gifted author.”

–Laura Farmer (The Gazette)

**

1. Lands of Lost Borders by Kate Harris

5 Rave • 4 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Kate Harris’ Lands of Lost Borders: A Journey on the Silk Road is a compelling, suspenseful, insightful and elegant travel memoir … The book moves seamlessly between the Silk Road adventure and backstory that led up to it … The book also moves easily between narrative and philosophy … There are certainly adventures. Dangerous roads around the Black Sea, mistaken imprisonment in a tea house, visa problems, bad weather, bad roads, hunger, illness, lost bicycles, and the seemingly ever-present kindness of strangers keep the book moving along. And there are certainly digressions into discussions of Darwin, Sagan, Polo, ecology and regional history. Every one of them is a thread you can’t undo … This is one that will have you dreaming.”

–W. Scott Olsen (The Minneapolis Star Tribune)

*

2. The Impostor by Javier Cercas, Trans. by Frank Wynne

4 Rave • 4 Positive

“Mr. Cercas’s book is several books at once, but, above all, it is a rigorous and obsessive quest to untangle what is true and what is false in the private and public life of Enric Marco … As well as an incisive piece of journalistic investigation, Mr. Cercas’s book is a subtle essay on the nature of fiction and the ways in which it can invade our lives and transform them … Mr. Cercas does not want to find this supreme impostor likeable and, so that no one can have any doubts on the matter, he heaps condemnatory epithets upon him at every turn … What is most striking is that the person who wins the game played out in this luminous book is not the straightforward Mr. Cercas but the devious Mr. Marco … Excellent novelist though he is, Javier Cercas was so fascinated by the theme and subject matter of his book that he forgot that good novels always turn the bad characters into good because they always end up exerting over readers … The book that he has written, even though he might not have wished it to turn out that way, is a (magnificent) novel about an uncommon character.”

–Mario Vargas Llosa (The Wall Street Journal)

Read an excerpt from The Imposter here

*

3. The Only Girl by Robin Green

2 Rave • 7 Positive

“The staccato sentences strung together cut into our emotions and deepen the stark, claustrophobic feeling of aloneness and disappointment and momentary hopelessness … The Only Girl is brimming over with stories of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, and there are clear-eyed but sympathetic descriptions of some of the more famous denizens of the magazine … Yet, the power of The Only Girl lies in Green’s willingness to acknowledge the vulnerability she feels early in her career, her willingness to share her struggles and triumphs of making her way, finding her voice … an electrifying read.”

–Henry Carrigan (No Depression)

*

4. Arthur Ashe: A Life by Raymond Arsenault

1 Rave • 8 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Raymond Arsenault has created a posthumous paean to Arthur Ashe … Arsenault has worked through interviews with those who knew Ashe, and also with Ashe’s own extensive personal writings, so that the man’s voice is heard again. This thorough account naturally will be of particular interest to sports fans … Arsenault’s book has the power to invade the hearts of those who did not experience the American Civil Rights movement directly.”

–Barbara Bamberger Scott (BookReporter)

*

5. Boom Town by Sam Anderson

3 Rave • 2 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Anderson is a great basketball writer…and his material on Harden, Durant, and particularly Westbrook in Boom Town will surely enthrall hoops fans. But Boom Town will also thrill anyone who couldn’t care less about the NBA; at its core, it’s a curious reporter’s portrait of the cultural and civic life of a strange and great city. If you’re a non-Oklahoman, you’ll experience frequent shocks of recognition at the foibles of the modern urban experience; Anderson’s explorations, though, will have you opening your preferred travel app, idly pricing tickets to the Sooner State … The cast of characters that Anderson has assembled in his book offers an embarrassment of riches, a testament to Anderson’s skills as both a reporter and a historical researcher … The imaginations of sports and cities reinforce each other rather perfectly, a connection that Boom Town mines for all its possibilities.”

–Jack Hamilton (Slate)

Read an excerpt from Boom Town here

“What is a poet? An unhappy man who hides deep anguish in his heart, but whose lips are so formed that when the sigh and cry pass through them, it sounds like lovely music.”

-Soren Kierkegaard

*

Celebrities, eh? Why can’t they just stay in their lanes? Not content with rising to the very top of their chosen fields, many of this nation’s most beloved movie stars, musicians, politicians, and James Francos have gone in search of less familiar dragons to slay. Some generous souls out there might look upon these monied vagabonds as modern day Renaissance people. Others (probably many, many others) would dismiss them as little more than bored dilettantes, trading on their renown and connections to rocket to the tops of mountains others have been doggedly, and usually unsuccessfully, climbing for years. I’m gonna go out on a limb and say that nowhere is this latter impulse felt more acutely than amongst the poets. Statistically the 13,354th least lucrative profession in the world (look it up), the last thing the poets need right now is some jumped-up little shit from Tinseltown sauntering into their Brooklyn reading series and/or Amazon sub-category and sucking all the air out of the room.

Still, they persist. Whether it’s Franco getting paid to do Hart Crane cosplay or Jewel having one of the best-selling poetry collections of all time (over 2 million copies shifted to date; I’m fairly certain only Rupi’s beating that figure), there are enough qualified success stories out there to convince, I’m sure, plenty more celebs that it’s worth swimming into unknown waters.

As we await the rise of America’s next top actor-poet, here are the first reviews of ten of our favorite celebrity poetry collections.

*

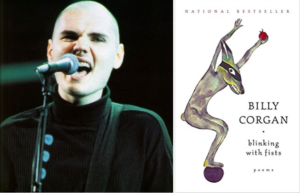

Blinking With Fists by Billy Corgan (2004)

Publisher said: “Crafted with a thoughtful and cadenced approach that shares the same allegiance to thunder and quiet found in his music, these writings further solidify Corgan’s place as the voice of a generation.”

Review said: “People are not buying Billy Corgan’s book because they are mistaking him for Billy Collins, the winsome former poet laureate. They are buying Blinking With Fists because Corgan, who led the influential band Smashing Pumpkins during the 1990’s, still has a following—he can seem like a geeky, gothy, brainiac version of Kurt Cobain. Corgan’s free verse is the kind of stuff that, if you’re skimming through looking for a line or two to ridicule, won’t let you down (‘I miss you already / Starting for home / The zombies keeping / All of it for themselves’). But at its best, Blinking With Fists is vivid and angular and not much worse than many first books of poems that arrive with heady praise from the poetry world’s burghers. In ‘Lost Gray,’ Corgan writes: ‘Stir, the crow cackle / Collar high / The angles black against the sides / Splitting in 2’s we swing clubs / Old fog rolls and hugs / Back slappin’ / Paying dues for crackjaws.’ I’m not sure I know what that means, but it beats the oracular utterances in Jim Morrison’s poems.”

–Dwight Garner (The New York Times)

*

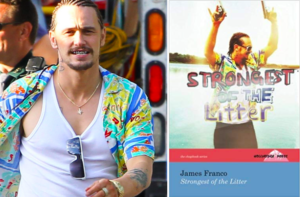

Strongest of the Litter by James Franco (2012)

Publisher said: “There is a vision of power at the center of James Franco’s first chapbook of poems, Strongest of the Litter. Power here is both generative and frightening, self-consuming and bracing. It is the artist’s power of self-making. These poems, thoroughly beautiful and spare, have the texture of contending angles.”

Review said: “Despite how anyone might feel, this chapbook is (chuckle to self) art. Despite being highly self-conscious, this is a whole new arrangement of letters and numbers on the page, and was written by a human being. It was irreverent for James Franco to write a book of poems and to modify language, and yes he was completely sincere. He’s not kidding. Not even like 1% kidding … these poems are about James Franco finding his authorial voice despite the fact that James Franco is temporal, he had never existed before a certain place in time and someday he will no longer exist as a body in a room. This is difficult for James Franco to negotiate. He will only exist as an artifact, and this is something that concerns James Franco on every page of this book … At no point in Strongest of the Litter do we lose our places. In fact I always know exactly where I am. I am sitting in my apartment reading a James Franco book. Time ticks by like an unsure and crippled ant. That is to say: Franco uses his fame as his subject. He does not want it any other way. This is his choice. Patti Smith does this too in her book Just Kids. It’s no new thing. However, Patti Smith is not hiding behind the machismo and preconceived notions of fame.”

–Amy Lawless (Vol. 1 Brooklyn)

*

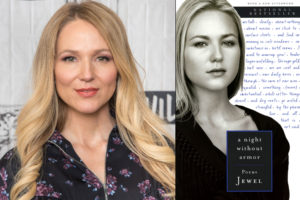

A Night Without Armor by Jewel (1998)

Publisher said: “Writing poems and keeping journals since childhood, Jewel has been searching for truth and meaning, turning to her words to record, to discover, and to reflect … Frank and honest, serious and playful … a talented artist’s intimate portrait of what makes us uniquely human.”

Review said: “Charles Bukowski once wrote, ‘To say I’m a poet puts me in the company of versifiers, neontasters, fools, clods, and scoundrels masquerading as wise men.’ Jewel Kilcher, a Bukowski fan responsible for the 10-million-selling pop-folk album Pieces Of You, is now happily joining this disreputable company with the release of her own collection of neontasting, A Night Without Armor. By now, Kilcher’s background is pop legend: A displaced Alaskan songstress living out of her van, she achieved great heights after being discovered in San Diego. Her image is so precious, so inflated in its storybook nature that it’s easy to want her poetry to suck outright or reveal too much of herself. It avoids that, but it also avoids many other things, such as deep insight into the human condition. Kilcher’s poetry is competent and sometimes evocative—most obviously in her barbed short poems—but her age and relative lack of experience show. When it comes to poems about sex, for example, she isn’t above resorting to purple clichés: ‘I’d be your hungry Valley / and sow your golden fields of wheat / in my womb.’ Sure, it’s more evocative than Ice-T’s ‘Let’s get butt naked / and fuck,’ but it’s not long on subtlety or cleverness, either. It’s hard to say what direction Kilcher’s poetry will take after this. Most of her influences, including the aforementioned Bukowski (or, as she spells it, ‘Bukowsky’) and Tom Waits, lived on the periphery for some time before being assimilated into popular culture, if at all. At 24, Kilcher may never again be able to escape into anonymity, and who really wants to read poems about how rotten it is to be rich and famous?”

*

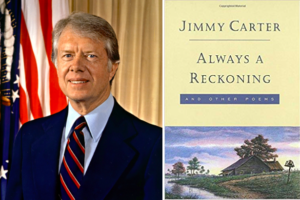

Always a Reckoning by Jimmy Carter (1995)

Publisher said: “The first collection of poetry by former President Jimmy Carter, who shares here his private memories about his childhood, his family and political life, with illustrations by his granddaughter.”

Review said: “At first glance, the vocations of poet and politician might seem completely antithetical. Poetry, after all, requires subtlety, introspection and fidelity to language, qualities not exactly valued by most politicians. Oddly enough, in the case of former President Jimmy Carter, the very qualities that helped cripple him as a politician are also the qualities that make him a mediocre poet … well-meaning, dutifully wrought poems that plod earnestly from point A to point B without ever making a leap into emotional hyperspace, poems that lack not only a distinctive authorial voice, but also anything resembling a psychological or historical subtext…

…

“What’s odd about these poems is that they give the reader plenty of information about Mr. Carter’s day-to-day experiences, while revealing little about his inner, imaginative life. The sentiments expressed tend to be generic ones, expressed in strangely abstract terms: sadness over a parent’s illness, nostalgia for childhood adventures, sympathy for the suffering of the poor, hope for a rosier future.”

–Michiko Kakutani (The New York Times)

*

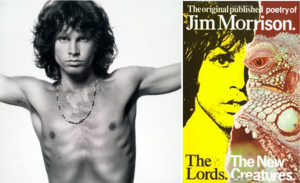

The Lords and the New Creatures by Jim Morrison (1970)

Publisher said: “An uninhibited exploration of society’s dark side—drugs, sex, fame, and death—captured in sensual, seething images. Here, Morrison gives a revealing glimpse at an era and at the man whose songs and savage performances have left their indelible impression on our culture.”

Review said: “Jim Morrison, lead singer and composer for ‘The Doors,’ gambols through indulgent ‘Bitter grazing in sick pastures.’ His characteristic fascination with incest, decay, death and dismemberment is all there; man retreats from reality into image, religion, alchemy, cinema (‘Camera inside the coffin interviewing worms’ and ‘A gray film melts off the eyes, and runs down the cheeks’). Morrison’s New Creatures are atavistic—’Lizard woman,’ ‘Jackal,’ ‘Mating-Queen.’ They are the natural enemies of the Lords whose ‘Art adorns our prison walls/ keeps us silent and diverted/ and indifferent.’ Provoking protest, subtle as a grenade, Morrison is equally sure of violent dislike or allegiance. When he’s good, he can transform even the unrecognizable into the commonplace.”

*

Yesterday I Saw The Sun by Ally Sheedy (1991)

Publisher said: “A collection of fifty poems that speak to the concerns of millions of young women, as Sheedy deals with love, men, and drug and alcohol rehabilitation.”

Review said: “Ally Sheedy is a wonderful poet. A collection titled Yesterday I Saw the Sun has just been published by Summit Books and is really moving. Ally told me she wrote the poems during various stages of her life since age 12. This is an extraordinary mind at work.”

–Larry King (USA Today)

*

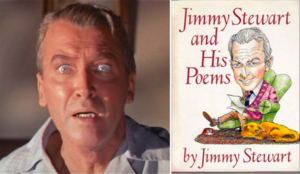

Jimmy Stewart and His Poems by Jimmy Stewart (1989)

Publisher said: “From fishing trips and dog stories to a hilarious account of a photo safari where the camera was lost to a hungry hyena, the poems are related in Jimmy Stewart’s inimitable voice and are enlivened with charming illustrations.”

Review said: “Jimmy Stewart. You love the guy, right? Me too. He’s a wonderful actor, a cultural treasure and an exemplar of the good, plain, American virtues. Now, the jacket copy of his new book says, ‘the consummate Everyman shares tales from his everyday life.’

‘I’m sure,’ Mr. Stewart tells us, ‘I never said to myself: “Now Jim—why don’t you sit down and write a poem.” It’s still a mystery to me.’ Isn’t that just the way of it? A fellow can be sitting around, doing no harm, and those muses will tackle him, throw him down and wrench poetry out of him. It’s a mystery, all right.

…

“He winds up with ‘Beau,’ a panegyric about a beloved dog: When he was young He never learned to heel Or sit or stay, He did things his way.

Mr. Stewart handles a trickier rhyme scheme in this one. The dog dies, and he misses him. It’s a heartbreaker.

The jacket copy of Jimmy Stewart and His Poems concludes that ‘the book confirms what we all expected—that the real Jimmy Stewart is every bit as endearing as the film characters he’s portrayed.’

Well, you’re not going to hear any argument from me.”

–Daniel Pinkwater (The New York Times)

*

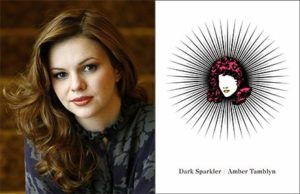

Dark Sparkler by Amber Tamblyn (2015)

Publisher said: “The lives of more than twenty-five actresses lost before their time—from Marilyn Monroe to Brittany Murphy—explored in a haunting, provocative new work by an acclaimed poet and actress … a surprising and provocative collection from a young artist of wide-ranging talent, culminating in an extended, confessional epilogue of astonishing candor and poetic command.”

Review said: “This third book of poems from actress Tamblyn could be a large-scale media event, but it’s also a good read … Here her poetic avocation takes on the perils of her primary career: the actress has created an energetic and formally varied collection focused on ill-fated starlets, dead actresses, and child stars. Some lines misfire, or sound garish, but many hit their mark … Reviewers may compare Tamblyn to James Franco, who also wrote poems about his own celebrity, but the two cases aren’t really alike: Tamblyn’s work seems less slick, and it’s more playful and far more personal, with highs and lows that stick around after the cameras are off.”

*

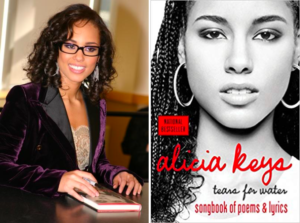

Tears for Water by Alicia Keys (2005)

Publisher said: “A revealing songbook of collected poems and lyrics that document her growth as a person, a woman, and an artist.”

Review said: “With their themes of loneliness, confusion, wonder and desire, most of Keys’s free-verse poems could be the cris de coeur of any American 20-something: ‘Sometimes I feel/ like I don’t belong anywhere/ And it’s going to take so long/ for me to get somewhere/ Sometimes I feel so heavy-hearted/ but I can’t explain/ cause I’m so guarded.’ But other poems hint at her world travels, her budding sense of social justice and her concerns about stardom (‘When gone is the glory/ When gone is the shine/ Is gone the whole/ Of your fortune and pride?;). Nearly half of the book consists of lyrics from her two albums, Songs in A Minor and The Diary of Alicia Keys; while they make a nice complement to the poems, the words feel a bit flat without the blaxploitation beat of ‘Heartburn,’ say, or the impassioned vocal delivery of ‘Fallin.’ For the Keys completist, however, this will be a compelling book of rock ephemera.”

*

A Piece of My Mind by Charlie Sheen (1990)

Publisher said: “Self-Printed (August 3, 1990)”

Review said: “Charlie is a personal friend of mine, and I have been reading his poetry for years. This collection is the best of the best as far as Chas’ art is concerned. When one works on a show like Full House, one sees many forms of expression (from ‘you’ve got it dude’ to ‘Watch the hair!’ [my personal favorite!]). Sheen expresses the overall feeling of the modern man. From our disgust with the system (damn the man) to our love of Sheenistry … Ok, ok. Some of Sheen’s poems may be seen as obscene, that’s what I hear anyway. Well, thats trash. that is like saying c. thomas howell is a bad tennis player. Its just flat out not true. Sheen steals part of ourselves and gives us a chunk of humanity and Sheenathan. And, everything that is Sheentastic … I know that Sheen has given us all something to think about. Ok, I know what you are thinking: He is a drug addict/alcoholic. Nope. First of all, as Sheen once said, ‘nobody ever told me it wasnt ok to have a good time.’ I’ll vouch for that. I’ve known the man for quite a while, and never, I mean never, during that time did anyone tell the man that it was not ok to have a good time. Now, time to get down to the nitty gritty. The poetry. It is outstanding. Brilliant. Fun. Did I say outstanding? Yeah. I am going to go out on a limb here. Are you ready? Sheen has produced the greatest book of all time. Did i say the greatest book of all time? Yes. The greatest book of poetry of all time? Nope. The greatest book of all time. Why? Well I’ll answer that. Sheen is willing to take on the greatest of topics. I wont spoil anything, but lets just say he runs the gamut from A to F. F stands for a bad word. Now im going to introduce a new word. Sheenastia. verb.—to live life with the greatest of detailed theological reasoning known to the human form.”

–John Stamos, or someone purporting to be John Stamos (Amazon)

*

Hungry for more reviews of celeb lit? Of course you are. Check out what happens When Celebrities Write Novels

Though often dismissed as a dead month in the world of book publishing, August 2018—and this past week in particular—has served up a veritable bounty of quality literary criticism. In her New York Times review of three recently-translated Scandinavian novels which explore chilling emotional territory, Gold, Fame, Citrus author Claire Vaye Watkins writes that Dorthe Nors’ Mirror, Shoulder, Signal, “sounds the depths of women’s unseen strength in a register that reconciles enlightened feminism with working-class rage.” Over at the Wall Street Journal, Peruvian Nobel Prize-winner Maria Vargas Llosa considers, in his analysis of Javier Cercas’ The Impostor (the true story of one of the world’s most infamous frauds), our need for fictions “to satisfy vicariously the hunger for unreality that dwells within us.” For the New Yorker, acclaimed essayist and Sooner State native Brian Phillips wrote about Sam Anderson’s Boom Town, “[a] dizzyingly pleasurable new history of Oklahoma City.” We’ve also got Neel Mukherjee on Deborah Baker’s The Last Englishmen—a sweeping account of the eccentric loners who made names for themselves during the dying days of the British Empire—and Alvin Buyinza on Joan Morgan’s a love letter to Lauryn Hill, She Begat This.

*

“As with the best books, plot summary fails to bottle the lightning of Mirror, Shoulder, Signal … The mind is Nors’s landscape, and yearning her true subject. Sonja’s is an objectless yearning, deeper than nostalgia. Page after addictive page, Nors pushes Sonja beyond her class betrayal and survivor’s guilt, beyond anger at her mother for encouraging her independence, into and, miraculously, out of a profound dislocation of the soul embodied by her vertigo, which bursts forth in a gorgeous, breathless finale.

Nora lingers on Sonya’s small acts of heroism: complimenting an ugly baby while its mother shops for plus-sized clothes, composing an honest letter to her housewife sister, offering a tourist directions. Nors gives the invisible woman the dignity of her artful gaze; as Sonja thinks on the masseuse’s table, ‘It’s wonderful being delved into.’ This triumphant novel sounds the depths of women’s unseen strength in a register that reconciles enlightened feminism with working-class rage.”

–Claire Vaye Watkins on Dorthe Nors’ Mirror, Shoulder, Signal (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“Mr. Cercas’s book is several books at once, but, above all, it is a rigorous and obsessive quest to untangle what is true and what is false in the private and public life of Enric Marco. He finds out many things: that Marco’s fabrications began in his youth, when he claimed for himself a past as a republican militant and an anarchist resistance fighter in the first years of Franco’s dictatorship, and that these fabrications shaped his entire existence. But also that these persistent lies are almost always laced with truths, lived experiences which he embellished, exaggerated, nuanced or played down to make the fictional ingredients he was constantly adding to his evasive biography all the more convincing. Mr. Cercas does not find everything out because the way in which fiction and reality meld in the life of Enric Marco is ultimately inextricable … All of us, all human beings, dream of being someone else, of escaping the narrow confines within which we live our lives. That’s why fictions exist: to satisfy vicariously the hunger for unreality that dwells within us and makes us dream of better or worse lives than the ones we are obliged to live. Through his daring, his talent for taking on different guises and his lack of scruples, Enric Marco managed, as in Rimbaud’s poem, to be both himself and someone else (‘Je est un autre’). As well as an incisive piece of journalistic investigation, Mr. Cercas’s book is a subtle essay on the nature of fiction and the ways in which it can invade our lives and transform them.”

–Mario Vargas Llosa on Javier Cercas’ The Impostor (The Wall Street Journal)

*

“In She Begat This, Morgan writes about Hill not as a subject to be studied but as a person to be humanized. Each chapter serves to connect her relevance to the greater black female experience, from her cover on Honey magazine, which became a symbol for black female representation, to her infamous downfall as the ’90s queen of rap. Morgan presents Hill as a black woman first and artist second. In doing so, she creates an authentic discussion on the racial politics of black womanhood. Among other things, the book gives spaces to black mothers … Morgan reminds us that black women cannot be saviors for the rest of world again and again and again. She remind us that ‘We turn mortals into gods—queens, if they’re only women—and then summarily pick them apart at the first hint of disappointment.’ Morgan’s book isn’t so much of a biography but rather a love letter to Hill, from one black girl to another. She draws personal experiences from multiple academics who are close to the works of Hill, making She Begat This a syllabus for the story of Black Girl Magic.

–Alvin Buyinza on Joan Morgan’s She Begat This: 20 Years of the Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (Christian Science Monitor)

*

“…[a] dizzyingly pleasurable new history of Oklahoma City. If ‘dizzyingly pleasurable’ and ‘Oklahoma City’ aren’t words you expect to see in the same sentence, Anderson’s book wants to convince you that the capital of America’s forty-sixth state is the most secretly fascinating place on earth … The effect of the cross-cutting structure is to turn the story of Oklahoma City into a kind of giddy Jenga tower, a mismatched jumble of fascinations. Since that is precisely what Oklahoma City is, this works. Anderson conveys not only the factual data about boom-and-bust cycles in the energy industry but the feeling of a city defined by them … Anderson’s working dichotomy for describing Oklahoma City’s history is Boom vs. Process: the tension between delirious growth and herculean planning. This makes for a riveting story, one from which I learned hundreds of interesting things. But, if you change the terms a bit, if you make the dichotomy Crowd vs. Loneliness, a different kind of analysis emerges: different ideas are thrown into relief. Anderson doesn’t talk much, for instance, about evangelical Christianity or ultra-conservative politics, two psychoses to which I’ve spent my whole life watching Oklahoma give way … Anderson writes beautifully about the human beings he encounters, both living and dead. A minute-by-minute account of the Oklahoma City bombing left me almost in tears.”

–Brian Phillips on Sam Anderson’s Boom Town (The New Yorker)

*

“…a dense, rich, exhilarating piece of work that moves deftly between worlds and peoples, between locations (Tibet, Cornwall, London, the Karakoram range, Berlin, Calcutta, the Garhwal mountains), between the private dramas of individuals and the tectonic shifts of history … Part of what the book achieves is a lucid rendering of the complex web of filiations and affiliations that connected not only these three central figures but also others in their orbit and in their disparate, often far-flung worlds … it is to Ms. Baker’s credit that she keeps the big events always in view, dramatizing and humanizing the workings of history, particularly the story of empire and its machinations, in a way a novelist would—by making it a story of individuals. She understands everything about these people, the details of their lives, the connections and the criss-crossings, intersections, overlaps, friends-of-lovers-of-friends. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that there is something Tolstoyan to her vast project. Ms. Baker’s other great achievement is an unsparing depiction of the hypocrisy, venality and inhumanity of British colonialism.”

–Neel Mukherjee on Deborah Baker’s The Last Englishmen: Love, War, and the End of Empire (The Wall Street Journal)

Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to writer and Millions Contributing Editor Nick Ripatrazone

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Nick Ripatrazone: I would have loved to write about Mariette in Ecstasy by Ron Hansen when it was published in 1991. Set in 1906, it is the story of a seventeen-year-old postulant who creates a scandal at the Sisters of the Crucifixion convent: her stigmata cause the sisters to become envious and malicious. I was recently able to write an appreciation of the novel for The Paris Review, but it would have been fun to write about it upon its release: when publications like Entertainment Weekly and The Village Voice were mesmerized by this book about the beauty and strangeness of faith.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

NR: Traci Brimhall’s latest book of poems, Saudade, is magnificent. She’s a storyteller in verse—such an agile writer, shifting between lineated poems, prose-poems, verse plays, and more to create a work that churns like a novel. The story of a community in Brazil, the book is rife with folk liturgy and pastoral rapture—Brimhall has a magical touch to make weirdness so palpable.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

NR: That criticism is utilitarian. It can serve that function, but I think criticism is performance. When I am charged by a book—when I love it, or hate it, or am confused and stirred by it—I am pushed to think about language and story in new ways. William H. Gass transformed my idea of criticism; he was playful, expansive, omnivorous. “The true alchemists do not change lead into gold, they change the world into words”—Gass would inhabit a book in order to write about it. My favorite criticism to write is when I feel possessed by a book—that has happened recently with The Carrying by Ada Limón and If You Have to Go by Katie Ford.

Another misconception—or perhaps an unfortunate truth—is that writers don’t like to be edited. I’ve worked with fantastic editors, and have learned so much from them. Writers need editors.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

NR: I’m a skeptical and private person. I try to be kind to others, but I think skepticism is a kindness to myself. Some people online (I’ll be honest: for me, they have always been men) act as if I owe them my time. I don’t. My time is for my family, and for myself. Although it might look like I’m “on” social media, I’m mostly passing through—and I would much prefer that people keep it moving. I’m sure that writers sent cantankerous missives to critics before the age of social media, but I worry that the ease of online communication has led to a drop in respectful distance. Twitter can be great—for example, Kaveh Akbar is generative, the type of person who inspires me to share poems I love—but Twitter can also feel like a crowded, smoke-filled room. Something like purgatory.

Also, I’ve written about this for Lit Hub: I think it is important for writers to share links to their work via social media, but to not worry about the response. That’s easier said than done, but the work is what is important—not the reaction. Learning to accept the silence is important, now more than ever.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

NR: I try to read everything that Vinson Cunningham and Meghan O’Gieblyn write. You can catch Cunningham in The New Yorker now, but he first caught my eye over at McSweeney’s, with the essay “On Sainthood.” O’Gieblyn’s book Interior States, a collection of her essays on everything from Hell to loneliness to niceness, is on my desk now.

I love what B.D. McClay is doing over at Commonweal (and I love that they, as a magazine, are supporting her as a contributing writer—it is absolutely essential that critics find a good home). Sentence-to-sentence, she’s a very talented writer: she’s precise and ambiguous exactly when she needs to be. I recommend her essay on Mary McCarthy (“Of Course They Hated Her”) and Catherine of Siena (“A Saint Born of Blood”).

There’s a trend here: as a reader and writer, I am most interested in signs and wonders, when the sacred meets the profane, and when the religious meets the secular.

*

Nick Ripatrazone is a Contributing Editor at The Millions, where he writes a monthly column on new poetry. He has written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, Literary Hub, The Poetry Foundation, and The Sewanee Review. The author of several books of poetry, fiction, and non-fiction, he is writing a new book about Catholic culture and fiction in America for Fortress Press. He tweets @nickripatrazone

*

Olivia Laing’s new novel, Crudo, is published next month. She shared her list of five books about love in the apocalypse with Jane Ciabattari.

Antigone, Sophocles

Antigone is the story of someone trying to do right, when what is right is against the law. It’s about valuing love, care, and decency above the rule of the state, and it remains unhappily necessary reading.

Jane Ciabattari: Antigone’s act of defiance of the state was a precursor to the civil disobedience we’ve seen in acts of resistance against contemporary state actions. Love and doing what’s right is so important Antigone is willing to die for her beliefs. Why do you think her actions still resonate today? Who are our modern-day Antigones?

Olivia Laing: Because we still have inhumane, supremacist states that do not treat all people with equal dignity and respect. If a state decides it’s okay for some people to suffer because of their place of birth or colour, whether that’s by caging refugees or perpetuating a racist police, then it has become inhumane. As for modern-day Antigones, three women spring to mind. Patricia Okoumou climbed the Statue of Liberty on 4 July this year in protest against the Trump administration immigration policies. In 2015 Bree Newsome climbed a flagpole in front of the South Carolina Capitol building and took down the Confederate flag. And in July this year a Swedish student, Elin Ersson, refused to take her seat on a plane until an Afghan man who was being deported was taken off. All three women have been punished and chastised for their actions, which were profoundly unselfish and in service of the freedom of others.

Goodbye to Berlin, Christopher Isherwood

Isherwood’s semi-fictionalised account of a young writer’s time in Berlin between 1930 and 1933 begins with romance and friendship and ends with Nazi parades, disappearances, and torture. It’s a frightening account of how an ordinary world can be altered inexorably by fascism, and the dispassionate witnessing is exemplary.

JC: Imagine setting a book in Weimar Germany that opens with this promise: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.” Ishwerwood witnessed the rise of Hitler. In the opening pages of your novel, Kathy, your narrator, notes, “The internet was excited because the President had just sacked someone. Got hired, divorced, had a baby, and fired in ten days.” She quotes Trump’s tweets, mentions the stream of images coming out of Charlottesville (“armed militias, crackers in camo armed with assault rifles”), and despite the growing atmosphere she prepares to get married. Did the political climate today inspire you to turn to fiction after biography, memoir, and criticism? And what makes it possible for Kathy to find love?

OL: Yes, absolutely. Goodbye to Berlin was very much my model for Crudo. When I began it in August 2017, I’d been trying for the past two years to write a non-fiction book about the body, but the turbulence of the times, and in particular the rise of fascism, was unignorable. I knew that if I wrote about the events of 2017 in my customary non-fiction style I would give it an orderliness and intelligibility it absolutely did not possess. So I turned to fiction, setting down real events through the eyes of Kathy, a cartoonishly paranoid, anxious, and selfish character who I felt epitomised something of our era. As in Goodbye to Berlin the constant shifts between a small personal life and the large political climate are queasy and disturbing. But unlike Christopher, Kathy doesn’t just want to be a camera. She wants to participate. She wants to be less selfish. She wants to admit to the reality of other people and their needs. She wants to love.

Happy Days, Samuel Beckett

Happy Days is about the illusions that keep us going. It’s bleak and pitiless, and yet there’s something almost consoling about the steadiness of Beckett’s stare into the abyss.

JC: The visual image of Winnie as she is gradually buried up to her neck in the course of two acts, is powerful. She’s always in the present as she speaks of her routine, her memories, often repeating “happy day,” hoping “‘something of this is being heard.” Her husband Willie never seems to listen. How can they have some sort of love ongoing despite it all? Is the fact he is there enough? Or the fact that she is still able to express herself, however haltingly, as her body and mind gradually fail?

OL: I don’t think they do have love ongoing. I think they are people who are locked together, and it’s hard to come up with a more dysfunctional, claustrophobic relationship in literature. Nor do I think Winnie’s blind optimism is anything to aspire to. What I’m encouraged by is Beckett himself as a witness: the fact that it is possible to make something durable even out of horror.

The Weight of the Earth, David Wojnarowicz

The apocalypse for the artist David Wojnarowicz was AIDS, a plague that annihilated friends and lovers, and which would eventually kill him too. He channelled his fury and despair into writing of unparalleled beauty and intensity. I love all his books, but this new edit of his audio diaries is especially intimate.

JC: Wojnarowicz died of AIDS in 1992, and these audio journals were recorded from 1981 to 1989, covering his relationships, his art, his emotional shifts. “Sometimes I wonder if I want to die or not,” he notes in May 1989, during a drive from Knoxville to Nashville. “I mean, if I wasn’t faced with this virus, how much would I want to live? And I remember Peter [Hujar] was always having those feelings. But I know that I want to live. At the moment, the road is reflecting this bright part of the sky that’s up ahead, and all the trees have receded into this thick dark green bordering both sides of the road. And there’s a gray cloud right at the end of the road and above that some strips of white pulling through the sky, and then there’s this blue, a really beautiful cobalt, very light with a lot of gray in it, and then above that more dark clouds in front of a strip of a bright-white cloud line. And then the gray heaven. And it’s really quite beautiful.” Despite the apocalypse, he was moved by the beauty around him, deeply committed to life. How do you think his illness affected his work?

OL: I have such an intense memory of sitting in the reading room at Fales, in the Bobst Library at NYU where the Wojnarowicz archive is housed, listening to those tapes through headphones. Wojnarowicz had a very deep distinctive voice and the impact of hearing him think aloud, speaking in such a painfully honest, unguarded way, was extraordinary. He was always a radically honest witness to his times, but I think his diagnosis made him exceptionally alert to beauty as well as injustice. As he says in Close to the Knives, smell the flowers while you can.

Modern Nature, Derek Jarman

Jarman’s diaries from 1989 and 1990 are another testament of the AIDS crisis, and yet they are also filled with moments of love and beauty. There’s Jarman’s joy at his late-flowering love affair with Keith Collins, and there’s the magical creativity of the garden he built opposite a nuclear power station on the shingle beach of Dungenness. If Jarman has one message, it’s that it’s always worth making the world better than it was.

JC: You’ve written of the influence of Modern Nature: “It was here I developed a sense of what it meant to be an artist, to be political, even how to plant a garden (playfully, stubbornly, ignoring boundaries, collaborating freely).” His voice is indelible. What’s your favorite passage from the book?

OL: What I really like in Derek’s writing is his movement between subjects. In a single entry, he might shift from domestic romance to political fury, or jot down garden notes about the lavender he’s planting, followed by a scholarly disquisition on medieval herbals and a joyful, sexy account of cruising on Hampstead Heath. Jarman lived a big life. He didn’t draw boundaries or allow himself to be limited by rules and categories. He insisted on freedom.

Sitting down to put this list together for #WiTMonth, I realized I had no idea where to begin. Some seriously amazing books by women have been published in translation recently. Last year gave us Ananda Devi’s Eve Out of Her Ruins (tr. Jeffrey Zuckerman), which won the 2017 CMLP Firecracker Award (and also knocked me flat), and Yoko Tawada’s Memoirs of a Polar Bear (tr. Susan Bernofsky), a lyrical reflection on displacement and belonging narrated by three generations of… polar bears (Tawada pulls off this unusual conceit with grace, aided by some truly exquisite phrases from Bernofsky). I’ve also been blown away by everything I’ve read of Marie Ndiaye (more on this soon), but I’m going to limit this post to new releases and titles I’m looking forward to in September or we’ll be here a long time.

Speaking of the latest and greatest, there’s probably little need for me to plug the lovely (and Man Booker International Prize-winning) Flights by Olga Tokarczuk, translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft and out this month (on this side of the pond) from Riverhead Books. The novel deftly explores, in limpid, captivating vignettes, the spaces we inhabit—bodies, geographies, the expanse of the page—and the loves, fears, and wonder that inhabit us. If this book somehow isn’t already on your reading list, here’s a whole slew of reviews to pique your interest.

But enough throat-clearing, let’s get down to it. A few recent literary marvels that should not be missed:

*

River by Esther Kinsky

Translated from the German by Iain Galbraith

Transit Books (September 2018)

In a similar vein as Flights, but with a more Sebaldian gait, River traces the movements and musings of a woman who decides to trade the Rhine for the River Lea and moves to the suburbs of East London without anything resembling a life plan. The book’s narrator, in Galbraith’s hypnotic translation, stares unabashedly at her new surroundings—and its inhabitants, who are treated with what might best be characterized as clinical warmth—amassing “beautiful, silt-like layers of description and memory until it becomes difficult to know which is which” (The Guardian). In addition to this internationally celebrated novel and two others, Kinsky is also the author of three collections of poetry, and it shows: with the force of the river’s current moving it forward, this is a book that draws you in, slows you down, and reminds you what it’s like to really look at the world around you.

Double take: a thoughtful review from The Mookse and the Gripes.

*

People in the Room by Norah Lange

Translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Whittle

And Other Stories (August 2018)

People in the Room is the first book by the avant-garde Argentine author Norah Lange (too long overshadowed by the men in her literary circle, including Jorge Luis Borges and Oliverio Girondo) to be translated into English, nearly 75 years after its original publication. Way ahead of its time, this experimental novel traces a young woman’s growing fixation on three women who live shrouded in darkness in the house across the street from her. Watching their nightly routine from her window, she imagines different scenarios that might have led them to spinsterhood, and the sinister plans they might be hatching behind closed doors; when at last she gains entry to the house, she grows even more entangled in their lives and the lives she projects onto them. While the obsessive and elliptical monologue of the book’s narrator might have been hard to follow in the hands of a less artful translator, Whittle has done an extraordinary job conveying the urgency and pathos of the young woman’s voice, making for a very compelling (and unsettling) read.

Double take: Sarah Gilmartin on this “macabre Argentinean classic” for The Irish Times.

*

Pretty Things by Virginie Despentes

Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan

Feminist Press (August 2018)

French writer, filmmaker, and punk rock feminist Virginie Despentes has been making major waves among readers of English lately: on the heels of Apocalypse Baby and Bye Bye Blondie (tr. Sian Reynolds), and King Kong Theory (tr. Stéphanie Benson), Frank Wynne’s translation of Vernon Subutex 1 (coming soon from FSG) was recently shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. Pretty Things elbows its way onto the scene with a penetrating look at the many different forms of violence—both public and intimate—that shape our society. The novel follows twins Pauline and Claudine as they hatch a plan to make Claudine (the “pretty” and image-obsessed one) famous by exploiting the vocal talents of her sister, who has never cared much for fashion or the spotlight. When the roles reverse and Pauline is the one who has to take over her sister’s identity, she discovers just how corrosive beauty and ambition can be. In Ramadan’s translation, Despentes’ prose crackles: bodies and sentences alike are fragmented, wrung out, hungover. This is a book to be devoured in one sitting—for a taste, check out this excerpt from the novel over at Lit Hub.

Double take: a starred review from Publishers Weekly.

*

Sexographies by Gabriela Wiener

Translated from the Spanish by Lucy Greaves and Jennifer Adcock

Restless Books (May 2018)

The Peruvian writer Gabriela Wiener is best known for her work in what might loosely be described as “gonzo journalism,” though her pieces tend to go deeper and are less inclined to hide behind swagger or sarcasm as she moves between historical research, social critique, and the confessional mode. Wiener’s trademark may be her insightful, emotionally raw first-person accounts of sexual encounters that fall outside societal norms (swinging, polyamory), but she also writes with remarkable power about taboo issues surrounding women’s bodies (egg donation, female ejaculation) and marginalized communities (the prison system, violence against LGBTQ+ people). Translators Lucy Greaves and Jennifer Adcock do an excellent job rendering the interwoven registers that make up these texts, and of keeping the essays vibrant and engrossing. The result is a searingly smart, surprisingly moving, NSFW gem. Intrigued? You can read Wiener’s pieces about tripping on polyamory and ayahuasca over at Words Without Borders.

Double take: here’s Sarah Booker’s review of the collection for Asymptote.

*

American Fictionary by Dubravka Ugrešić

Translated from the Croatian by Celia Hawkesworth and Ellen Elias-Bursać

Open Letter Books (September 2018)

Presented as a series of dictionary entries on topics ranging from the concrete (“Jogging,” “Mailbox,” “Bagel”) to the conceptual (“Homeland,” Personality,” “Melancholy”), American Fictionary is a collection of vivid, insightful essays about the particularities of life in the United States, and also about Ugrešić’s experience observing these particularities as a stranger while the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s tore her world back home apart. “By writing,” Ugrešić tells us, “I have tried to put my scattered words (and scattered worlds) into some sort of order. That, I think, is why I called it a dictionary.” (Later, a typographical error turned the text into a “fictionary” and Ugrešić was disturbed to realize that it was, in fact, probably a better description of the illusion of order she had been clinging to.) The observations presented in American Fictionary are just as relevant today as they were back then, when Ugrešić (winner of the 2016 Neustadt Prize and author of more than a dozen internationally celebrated books) was living in Connecticut as a visiting scholar. This wise and witty collection—its balanced tone expertly rendered by Hawkesworth and Elias-Bursać—is essential reading for anyone trying to sort through this fraught, exhilarating, contradictory moment in which we find ourselves.

1. Severance by Ling Ma

4 Rave • 4 Positive

“Ling Ma’s shocking and ferocious novel, Severance, is a play on the ‘Why I left New York’ theme, but it’s one you’ll actually want to read … a fierce debut from a writer with seemingly boundless imagination … Severance goes back and forth in time, contrasting Candace’s tedious office job with her travels across post-apocalyptic America. It’s a technique Ma uses to great effect — it’s jarring in a great way, making the horror of her new circumstances all the more intense … while Severance works beautifully as a horror novel, there’s much more to it than that. It’s a wicked satire of consumerism and work culture … Severance is the kind of satire that induces winces rather than laughs, but that doesn’t make it any less entertaining … [a] a stunning, audacious book with a fresh take.”

–Michael Schaub (NPR)

Read an excerpt from Severance here

*

2. Ball Lightning by Cixin Liu, Trans. by Joel Martinsen

3 Rave • 4 Positive

“Not only brilliant books in their own right, the Remembrance of Earth’s Past saga serves as a reminder of the presence of impressive and unique science fiction outside the English-speaking world … another intriguing, cerebral scientific mystery … Liu covers a lot of scientific and philosophical ground, and he’s not afraid to slow things down to allow his characters to discuss the real-world underpinnings of their work, or the virtues of, for example, pure versus practical research. Some might regard these dips in the pacing as a flaw, but for Liu, the digressions seem to be the point … he builds tension as masterfully as ever.”

–Ross Johnson (The Barnes and Noble Review)

*

3. The Air You Breathe by Frances de Pontes Peebles

3 Rave • 4 Positive

“An absolute masterpiece … Peebles is a master at sustaining dramatic tension, a wizard with intrigue and language, and a skilled curator of intimacy. She knows when to give context… and when to allow a thing to be a thing … Even more challenging is the ability to be able to create unapologetic antiheroes, which Peebles excels at … The tension created by these elements—the sociopolitical context, the drama of interpersonal relationships and queerness, and the high-stakes nature of subsisting off art—make a masterful book, sure to enthrall from beginning to end.”

–July Westhale (Lambda Literary)

*

4. Eleanor, or, the Rejection of the Progress of Love by Anna Moschovakis

2 Rave • 5 Positive • 2 Mixed

“A book about the inner lives of our contemporaries must be conversant with how it feels to live right now, and at this Eleanor excels. Not in the weak sense of name-dropping popular websites, fashionable trends, and political slogans, rather in the much stronger sense of understanding how we use those things to construct our identities and live our lives … Moschovakis has created a novel of great strength and flex. Much as it bends and twists and gyres, it does not break, in fact only accumulates more tensile strength from the motion, just as, one hopes, we all can do.”

–Veronica Scott Esposito (The Brooklyn Rail)

*

5. Desolation Mountain by William Kent Krueger

2 Rave • 4 Positive

“If his loyal spirit, derring-do, Iron Range ruggedness and protect-my-people nature don’t hook you, an irresistible story line will … Krueger keeps up the tension and mystery in this, the 17th Cork O’Connor novel, partly through his comfort with real places—Iron Range towns, Iron Lake and other familiar treasures. He uses them to develop an uncanny sense of place and purpose; we can almost smell the pines and see the reflection of the moon on a cold lake. Krueger has an obvious affection for his richly developed, recurring characters … Krueger’s taut storytelling and intricate plots almost always center on a topic in the news, a compelling hook he’s researched well and has wrapped his tale around.”

–Ginny Greene (The Minneapolis Star Tribune)

**

1. A Life of My Own by Claire Tomalin

6 Rave • 5 Positive

“A Life of My Own, is on one level a phlegmatic tour of a fruitful life … On another level, the book is one shock after another … A Life of My Own has a formal quality. Occasionally there is the unhappy sense that Tomalin is viewing her own life from too great a distance, as if she were a biographer working through a stranger’s life from file cards. She is a fluid writer but not the sort to go in search of le mot juste … Yet there is genuine appeal in watching this indomitable woman continue to chase the next draft of herself. After a while, the pages turn themselves. Tomalin has a biographer’s gift for carefully husbanding her resources, of consistently playing out just enough string. When she needs to, she pulls that string tight.”

–Dwight Garner (The New York Times)

Read an excerpt from A Life of My Own here

*

2. Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy by Anne Boyd Rioux

4 Rave • 4 Positive

“From the vivid, fire-lit opening scene, with the teenage Marches bemoaning their poverty and the prospect of Christmas without their father, each girl has a distinct voice that hints, as Ms. Rioux says, ‘at her unique personality.’ … the author observes, ‘Alcott’s classic pointed the way not only toward girls’ future selves but also toward the future relationships they could have with men and with each other. She imagined her characters moving into a mature womanhood that achieves self-fulfillment as well as shared joys and responsibilities, a storyline today’s little women desperately need.’ She’s right about that. The thoughtful pages of Meg, Jo, Beth, Amyamount to a plea: Let us not forget these girls! We still need them.”

–Megan Cox Gurdon (The Wall Street Journal)

“Why Don’t More Boys Read Little Women” by Anne Boyd Rioux

*

3. Chopin’s Piano by Paul Kildea

4 Rave • 3 Positive

“While it is assumed that most readers are aware that the Nazis looted art, what isn’t as well known is the theft of other cultural symbols such as musical instruments. Kildea does an excellent job of tracing and attempting to solve the mysteries of what happened to one of these iconic symbols. The author’s enthusiasm for the subject is very apparent and he expertly and effortlessly illustrates how Landowska’s trials and tribulations relates to Chopin’s, a saga which redefined portions of the cultural and political history of mid-20th century. Captivating and intriguing, Chopin’s Piano will most certainly entertain both novice and hardcore music historians.”

–Michael Thomas Barry (The New York Journal of Books)

*

4. Revolution Française by Sophie Pedder

2 Rave • 4 Positive • 1 Mixed

“As Sophie Pedder notes in her excellent and lavishly sourced account of Macron’s ‘quest to reinvent a nation,’ the French promise to reform at home—and conforming with EU fiscal rules is just part of a package of domestic measures designed to reassure Berlin—is a quid pro quo. In return for seeing through unpopular changes to the supply side of the French economy, as well as stabilizing the public finances, Macron expects Germany to support his ambitious plans for deeper integration of the eurozone … Pedder is sensitive…to Macron’s capacity for looking ridiculous—his avowed aim to be a ‘Jupiterian’ president will have elicited smiles in chancelleries across Europe. But she also recognizes that he has thought deeply about the symbolic weight that the presidency carries.”

–Jonathan Derbyshire (The Financial Times)

*

5. Playing Changes by Nate Chinen

2 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Nate Chinen has written a terrific book about the shape of contemporary jazz, and right now is a terrific time to read it … Instead of looking for tidy torch-passings or binary clashes between competing schools and styles, his ecumenical ear glides across the entirety of the greater jazz ecosystem, listening for the good stuff … The book’s arrival ultimately feels so well-timed … you don’t have to sit around and wonder what it all sounds like. Just reach for that little computer in your pocket and press play … Each album Chinen has chosen is worth at least one spin on your handy pocket computer … Playing Changes encourages us to listen to jazz the same way we might try to live life: Start anywhere, go everywhere.”

–Chris Richards (The Washington Post)

Read an excerpt from Playing Changes here

The reviews are in for reality TV show contestant turned Devil’s advocate turned recording artist Omarosa Manigault Newman’s insider account of the Trump White House, Unhinged, and they are, eh, not very good. Our favorite of the many, many pans the book has received in its first week of publication is Doreen St. Félix’s New Yorker evisceration, in which she writes: “Much of the book’s information is mundane, already reported on, or unsubstantiated. The arc turns on an inane semantic argument and the fact that, coincidentally, right around the time Omarosa had to find a new gig, she realized Trump was a racist.” Over at the London Review of Books, Conversations With Friends author Sally Rooney considers Sheila Heti’s auto fictional inquiry into the decision to have children, Motherhood, alongside the terrifying thought of “the women in 20th-century Ireland who spent their fertile years perpetually pregnant or nursing.” Legendary magazine editor (and long-time chronicler of the lifestyles of the rich and famous) Tina Brown reviews Anne de Courcy’s account of the Gilded Age American heiresses who married into the British Aristocracy, The Husband Hunters, for the New York Times Book Review. We’ve also got Rachel Riederer on Orca—Jason Colby’s history of our relationship to the Ocean’s greatest predator—and novelist and Iraq War veteran Matt Gallagher on Pulizer Prize-winner C.J. Chivers’ portrait of modern warfare, The Fighters.

*

“In short, you don’t really need to read Unhinged, which recalls Carrie Bradshaw bloviating at her desk at midnight. (‘I had to wonder, if Trump used the N-word so frequently during that season of the show, had he ever used it to refer to either Kwame or myself?’) Much of the book’s information is mundane, already reported on, or unsubstantiated. The arc turns on an inane semantic argument—that ‘there is a difference between being a racist, racial, and someone who racializes’—and the fact that, coincidentally, right around the time Omarosa had to find a new gig, she realized Trump was a racist … she can’t seem to choose between dressing herself as a bushy-tailed mentee, whose abstracted loyalty precludes her from seeing the misogyny and racism of her ‘mentor,’ or a savvy career woman, who was willing to play dirty to get ahead … Opportunism has never morally burdened her, which makes her self-interest seem both egregious and banal. She has clung to her infamy, in part, by perverting the black worker’s experience of racism. She has always exploited the vantage of the pariah, but has more frequently tried to frame herself as a victim.”

–Doreen St. Félix on Omarosa Manigault Newman’s Unhinged (The New Yorker)

*

“She makes a persuasive case that a prime driver in the American heiress exodus was escape from the savage competitiveness of Gilded Age society in the capital of status, New York … The Husband Hunters has a lot to say about the young American women who married titles, but at heart it’s a wonderful study of monster mothers … If American society was a cutthroat matriarchy, the world the heiresses married into was exactly the reverse. In England, the men called the shots. A gilded girl who thrived in an urban setting and was used to seeing women get their own way now found that the sparkle of London was confined to the three months of the summer social season. Life as the chatelaine of an English country seat revolved around the sporting calendar and dour male management of the estate. (This is still true today, as Meghan Markle will discover after a few weekends with Harry’s friends.) … What impresses about de Courcy’s American imports is how efficiently they adapted their native skills to England’s resistant class structure. They deployed not only looks and flair but also an organizational dynamism that whipped the stately homes and their owners into shape. They were brave. They were venturesome. They opened the windows of English aristocratic life, culturally as well as literally. It wasn’t just their money. With all that drive, all that enterprise, they were just what was needed to shake the cocktail and bring some pizazz to the party.”

–Tina Brown on Anne de Courcy’s The Husband Hunters (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“Like his previous work, The Fighters immerses readers in know-how and gravitas, bringing together a collection of war testimonies by infantry grunts, fighter pilots and hospital corpsmen. The battle fragments can’t provide a full picture of the wars they portray, but together they do form something else: a dark and honest reckoning with just what it is we’ve done since that empty blue-skied day was filled with smoke nearly two decades ago … Mr. Chivers crafts a vast and absorbing mosaic … Themes of betrayal and unintended consequence serve as the book’s marrow … Still, acts of great courage rise in The Fighters … His writing shines with careful understatement and a muted irony … And when Mr. Chivers does let it rip stylistically, you notice … This is not a book that details the strategies of generals and presidents … I’m more than sympathetic to this approach but still found myself wondering if some strategic perspective would have broadened the book … With breadth and raw truth, The Fighters lays bare just how exacting and brutal that duty [of fighting in U.S. wars] has been.”

–Matt Gallagher on C.J. Chiver’s The Fighters (The Wall Street Journal)

*

“When I think of the women in 20th-century Ireland who spent their fertile years perpetually pregnant or nursing, I don’t feel inspired; I feel terrified. Such women do deserve congratulations, for having survived. But having 19 children doesn’t strike me as a better or more important achievement than having one—or none … other real events and circumstance inform Heti’s narrative—but Motherhood works, as novels should, by putting questions of literal truth to one side … In Motherhood, Heti continues the project of How Should a Person Be? in at least one way: by opening out seemingly individual experiences into a general inquiry about ways of being. Despite its cyclical form, Motherhood is not so much a document of uncertainty and indecision as of the narrator’s slow and halting decision to live without children…Having babies is no doubt very interesting, but part of the point Heti is making is that not having babies can be interesting too; that living eternity backwards through one’s ancestors could be just as fulfilling as living it forwards through one’s children … The moral conundrum involved in the decision to create a new life can’t be resolved in the space of a novel—but Motherhood gives it sustained and serious attention.”

–Sally Rooney on Sheila Heti’s Motherhood (The London Review of Books)

*

“It is a story not just of the orca business, but also of the evolution of Americans’ relationship to the oceans and marine life—the growth of marine parks parallels the shift from an extractive approach to the ocean, as mainly a source of fish, to a recreational one. It intersects, too, with the birth of the modern environmental movement in the 1960s and 70s … For a generation that grew up on Shamu or Free Willy, anecdotes that Colby shares of orca hunters in ‘the Old Northwest’ are shocking … As the backlash against the industry rises, the irony is clear: The captivity and display industry made people love orcas, and then hate the captivity and display industry. This is the central thrust of Colby’s book, and he returns to the point throughout … More interesting, to me, than the judgment of history, are the moral compasses of the crying men themselves, who knew—well before Greenpeace protestors and Blackfish and the Marine Mammal Protection Act—that the animals they were hurting were sentient and sensitive; that they were doing something wrong … it’s also a story of the intellectual hoops that we humans will jump through, like well-trained marine mammals, in order to justify the harm done in the course of making a living, or just doing whatever we want.”

–Rachel Riederer on Jason Colby’s Orca (The New Republic)

Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to Brooklyn-based writer and critic Julian Lucas.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Julian Lucas: I’d review Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, the most unfairly neglected among my favorite books. Reed’s novel is a brilliant satire of the Harlem Renaissance that doubles as a Voodoo detective novel, cultural appropriation ur-text, and ersatz holy book. Carl Van Vechten—the photographer, writer, and noted “Negrophile” who Columbused the Harlem Renaissance—is portrayed as a deathless medieval Crusader scheming to save Western Civilization by neutralizing black culture, which has literally gone viral in the form of the pandemic “Jes Grew.” It’s mad, unadulterated genius—as many writers and academics have since recognized—but critics at the time couldn’t handle it. Reed was nominated for the 1972 National Book Award for Fiction, but lost to John Barth’s Chimera, which I don’t think has stood up as well. I wonder if things might have gone differently had Mumbo Jumbo received even one more open-minded review.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

JL: The Fearless Benjamin Lay by historian Marcus Rediker. It’s a short yet extremely inspiring biography of America’s first radical abolitionist, a vegetarian Quaker dwarf who lived in a cave near colonial Philadelphia. As far as I’m concerned, he was the wokest white man to ever live. Benjamin Franklin (who remarked on his terrible breath) helped Lay publish a treatise entitled All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, which compared his respectable slave-owning neighbors to the Beast in the Book of Revelations. Lay was gloriously uncivil. At one Sunday meeting in New Jersey, he spattered the congregation’s slaveholders with pokeberry juice before being dragged out. Today, he’d doubtless be considered a dangerous Antifa terrorist poisoning our national discourse. But he was really a tender-hearted eccentric with preternatural moral courage, an abolitionist before abolitionism. If only he’d rise from the dead and run for office in Trump country.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

JL: I don’t know if this is a misconception, but many people seem to believe that reviews are only useful before deciding to read a book. But if the review is truly insightful, reversing the order can be more enriching. I can’t tell you how many times reading a critic has sharpened my sense of a book, whether because they articulate a perception I didn’t have words for or because objecting to their judgment helps me delineate my own. More casual readers could appreciate criticism if they approached it this way—as a way of reflecting with others on a literary experience, rather than condescending instructions on what to read and think. That’s another misconception about critics, that we want people to think exactly as we do—but even if that were possible, it would only make us irrelevant.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

JL: As a mere millennial, I have no memory of book criticism before the age of social media, a phrase that makes me picture Neolithic soothsayers conjuring memes in smoke. But I think the collision of spheres it facilitates is both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it makes it easier for ideas to find their audience, and harder for reviewers to hide from the scrutiny of those beyond their publication’s usual readership. On the other hand, there is more pressure to consider every possible viewpoint when the audience is potentially everyone. Overall, I hope that much as film and television pushed fiction toward what only it can do, social media might force criticism to embrace its own singularity. Literary reviews at their best are not just “takes” but landscapes of context, revealing facets difficult to grasp when you read a book in isolation. You know how you might “know” someone, but when you visit their home, or meet their family, or hang out with their friends, something changes? That’s what a great review can do for a book.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

JL: Doreen St. Félix is always insightful and has an intuitive grasp of American media metaphysics. I admired her profile of Kara Walker in New York and her essay on appropriation, memes, and Vine for The Fader. Parul Seghal never fails to be interesting, regardless of what she thinks of a book, and her prose is exquisite. I read every review Brian Dillon writes at 4Columns. (His excellent book Essayism comes out in the US with New York Review Books in September.) Finally, Frank Guan wrote one of my favorite essays this year in The Point, where I’m web editor. It’s a review of Elif Batuman’s The Idiot that also extends her criticisms of contemporary fiction. Guan asks why so many novels refuse to engage with ideology, and the stultifying consequences of having characters with refined perceptions and complicated feelings but no politics or worldview. It’s an essay that not only identifies a lack, but suggests a way forward.

*

Julian Lucas is a writer and critic based in Brooklyn. He is an associate editor at Cabinet and web editor of The Point. His essays and reviews have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The New Republic, and the New York Times Book Review, where he is a contributing writer. He is working on a book of essays. @jcljules

*

Kwame Anthony Appiah’s new book, The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity, is published this month. He shared his list of five books about individuality and identity with Jane Ciabattari.

*

On Liberty, John Stuart Mill

In Chapter Three, “On Individuality as one of the Elements of Well-being,” Mill offers an impassioned defense of the idea that each of us has to “find out what part of recorded experience is properly applicable to his own circumstances and character.” It’s his balanced sense that each of us is both particular and distinct and yet, at the same time, shaped by our social circumstances, that makes this discussion of individuality so inspiring. Mill’s discussion anticipates the best contemporary thoughts about selfhood. “Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing.”

Jane Ciabattari: Reading these passages from On Liberty is oddly emotional, as I am pained by the fact we seem to be situated in a binary time, with the more spacious sense of individuality which I prize on the wane. Do you believe the complicated relationship between individuality and social identity shifts in cycles? Are we due for another shift?

Kwame Anthony Appiah: I’m not sure that there are cycles, but there are certainly historical shifts in the salience of different sorts or dimensions of identity. Mill was worried about a kind of flattening of the social world in which increasingly uniform and universal modes of education combined with the pressure to conform—the tyranny of the majority—produced people who were more and more difficult to distinguish from one another. So On Liberty celebrates not just genius but also eccentricity. He thought that we all profit from both, even when we are challenged or threatened by them. But above all he thought that each of us should make our own lives. He says: “If a person possesses any tolerable amount of common sense and experience, his own mode of laying out his existence is the best, not because it is the best in itself, but because it is his own mode.”

There are actually two important ideas in Mill. First, that we are different and so need different circumstances to flourish. But second, that what matters in a life depends, in part, on the choices of the person whose life it is. One problem in our time is that the first of these thoughts can lead people to say, “This is my identity, so I must live it out.” But that can actually make your life less your own, and drive you away from finding your own particular “mode.” Talk of authenticity—racial, ethnic, religious, national—can actually be a straitjacket, because the authentic self turns out just to be the expression of some group. And that’s probably the worry that makes you think there’s something moving in Mill. So I guess it’s worth pointing out that one can take up a racial identity, say, and use it to make one’s own original life. It’s just that it’s important to make sure that you tailor the off-the-shelf outfit to your own developing self.