Somehow it’s late September, which means there’s a chill in the air and just about everything seems to be careening away from the delicious torpor of summer. But it’s not all bad news. September is also National Translation Month, and exciting things have been happening all around. For instance: Words Without Borders announced that Chad W. Post will receive this year’s Ottaway Award for the Promotion of International Literature. Chad has been a champion of literature in translation for more than a decade, from founding and running Open Letter Books, to establishing the Best Translated Book Award and blogging/podcasting about translation, maintaining the invaluable translation database, and… and… and… So: three cheers to him and to the wonderful WWB. (Check out this month’s special issue on writing from Georgia.)

Then there was the announcement of the longlist for the inaugural* National Book Award for Translated Literature. I was thrilled to see my translation of Roque Larraquy’s Comemadre alongside widely recognized works like Yoko Tawada’s The Emissary (tr. Margaret Mitsutani) and Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights (tr. Jennifer Croft), and books I can’t wait to check out, like Dunya Mikhail’s The Beekeeper (tr. Dunya Mikhail and Max Weiss) and Perumal Murugan’s One Part Woman (tr. Aniruddhan Vasudevan).

Anyway, whether because of the frantic rhythm of fall or the waning daylight hours, my mind turned this month to compact and often unsettling worlds that unfold in a single sitting. Here’s a mix of recent favorites and titles I’m still recommending as the years go by:

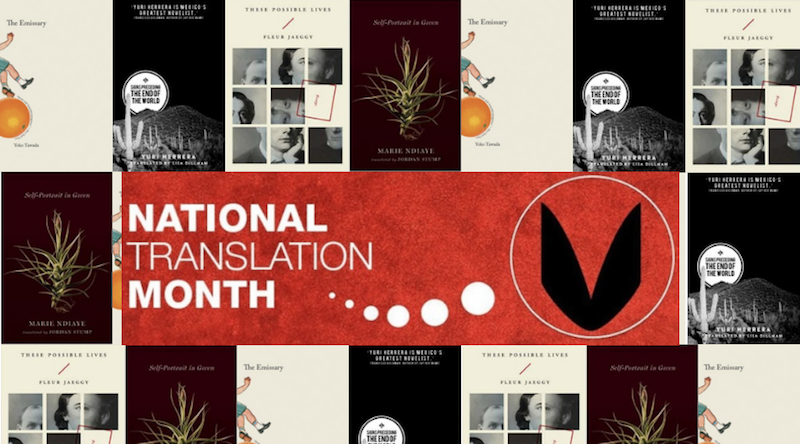

The Emissary by Yoko Tawada

Translated from the Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani

New Directions (April 2018)

In the wake of an ecological disaster that has turned its soil to poison and generated extraordinary mutations in its flora and fauna, Japan finds itself cut off from the rest of the world and on the brink of societal collapse. Children are born so weak they can barely muster the energy to eat the food they need to survive, while the elders of the community outlive generation after generation of their descendants. Against this backdrop, the elderly but robust Yoshiro is charged with caring for his great-grandson, Mumei, a sweet and exceptionally intuitive young boy who might just be the envoy this desperate society needs. In the barren landscape of this slim novel it isn’t just the population that’s dying off: language itself seems in danger of extinction, due in large part to the tariffs and restrictions on foreign words since Japan closed its border—a situation painfully reminiscent of the current pandemic of xenophobia and the soggy jingoism of Freedom Fries. All told, The Emissary is a complex and startling dystopian fiction that, in Mitsutani’s translation, skates deftly between the apocalypse and the kitchen table, bleak prophecy and cheery aphorism. This is a strange world indeed, and I didn’t want to leave it.

Double take: Andrew Hungate on the work and its context, over at Words Without Borders.

Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera

Translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman

And Other Stories (March 2015)

I can’t imagine what could possibly be turning my mind to borders these days, but reading The Emissary reminded me of another remarkable short work—one of my favorite books of recent years, in fact, which I teach/push/praise every chance I get. Together with The Transmigration of Bodies (2016) and Kingdom Cons (2017), the Best Translated Book Award-winning Signs is part of what could be described as a border trilogy: narratives centered on the circulation of bodies, and violence, back and forth between Mexico and the United States (though Herrera draws his narrative maps with allusions rather than specific place names). This brief novel—recently adapted for the stage at the 2018 Edinburgh International Book Festival—begins with the earth literally falling out from under the feet of its protagonist, Makina, a young woman who will undergo a series of trials on her quest to deliver a message to her brother; he disappeared years earlier while searching on the other side of the border for a plot of land promised to their family. In order to cross, Makina first has to pass through various criminal underworlds; once on the other side, she finds herself in a place where “signs prohibiting things throng in the streets, leading citizens to see themselves as ever protected, safe, friendly, innocent … salt of the only earth worth knowing.” And full of lunatic vigilantes with shotguns, of course. As in the Tawada, reflections on language hold pride of place; unlike The Emissary, however, which hums with claustrophobic tension, Signs feels vast: Makina’s story is told in a Spanish brimming with neologisms and inflected with a wide range of linguistic and cultural references from across the centuries, a Herculean task of translation to which Lisa Dillman responded with stunning grace and acuity.

Double take: Maya Jaggi teases out the book’s the tightly woven allusions for The Guardian.

These Possible Lives by Fleur Jaeggy

Translated from the Italian by Minna Zallman Proctor

New Directions (July 2017)

And now for something completely different. The tiniest of this month’s tiny books, These Possible Lives, by the reclusive Swiss writer Fleur Jaeggy, is made up of three biographical sketches—or perhaps more accurately, death masks—of Thomas De Quincey, John Keats, and Marcel Schwob. To me, the greatest wonder of this work is how Jaeggy, and then Proctor, managed to wring so much poetry out of such compact sentences (Sheila Heti explores this facet of Jaeggy’s writing in a piece for The New Yorker on Jaeggy’s short story collection I Am the Brother of XX, which is exquisite and could just as easily have been the focus of this write-up). De Quincey’s entry into the world of opium “was like being a guest in the pages of a richly illustrated encyclopedia for children,” while Keats “looks like a girl, and if we think of him as a girl, the femininity of his features evaporates and he seems stubborn and volatile, the constant surveyor of his own visions.” These strange and beautiful portraits cast familiar faces in an unfamiliar light, whittling down their imposing subjects until what is left is a finely-wrought catalog of vanities, superstitions, desires, and fears.

Double take(s): Emily LaBarge digs into the dark recesses of this gem for the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Martin Riker sets it in the context of Jaeggy’s other work for the New York Times.

Self-Portrait in Green by Marie NDiaye

Translated from the French by Jordan Stump

Two Lines Press (November 2014)

Last month, I alluded to my (completely measured and reasonable) obsession with Marie NDiaye, a virtuosic writer who published her first book at the age of 17, followed that up with a 200-page novel written in a single sentence, and then went on to win the prestigious Prix Goncourt in 2009 for her Trois femmes puissantes. Well, this slim, enigmatic volume is where it all started for me. Self-Portrait operates at the place where narrative meets memoir, bringing together fragmentary encounters with the women in green, a melancholy parade of figures living and dead whose strength has been forged in neglect and fed by regret (theirs and others’). In one storyline, a woman named Jenny pays a daily visit to the wife of her ex, who shares with her the minute details of her life with the man Jenny rejected years earlier. When asked why the woman should volunteer this information, the remorseful Jenny responds, “To console me.” In another, the author’s own mother turns into one of the “most alien and troubling forms” of the so-called “green woman,” while in a third, the high-school friend who became NDiaye’s stepmother lives in poverty and frustration under the thumb of the author’s father. These women, disparate yet united in their desperation, are all also—as the title suggests—NDiaye: they both define the contours of her world, and speak to a shared experience. Each time I return to it, I’m left speechless by this powerful meditation on the complex relationships among women.

Double take: Patty Nash for Asymptote on the curious art of the self-portrait.

* As M.A. Orthofer points out in his write-up of the NBA list, an award for translation was given out between 1967 and 1983.