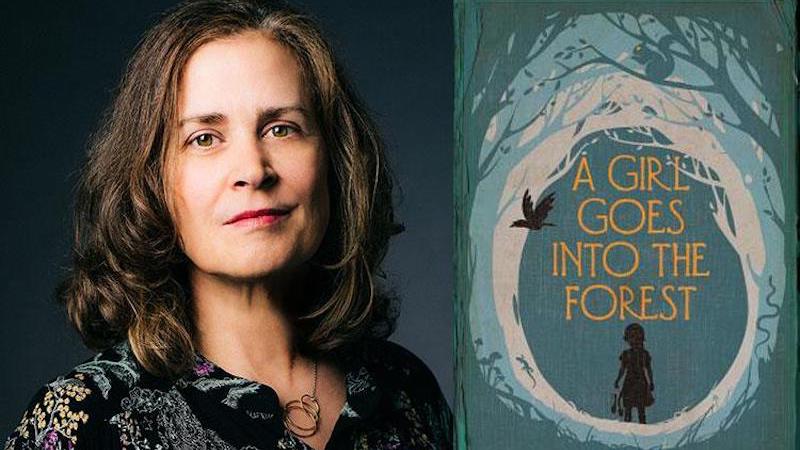

Peg Alford Pursell’s A Girl Goes into the Forest is published today. She shares five books of hybrid form, noting, “I’ve always been drawn to books that don’t fit neatly into labeled categorizations. Books that defy the boundaries, that combine, transform, and subvert conventions, show what’s possible. They offer ways of seeing the limitations of any one form, suggesting that even more is possible. Nonbinary forms seem truer in their reflection of our world and of us, people. By blending and/or bending genres such books open up into the liminal, where it seems to me one’s pulse picks up. What I want most these days from my reading is that—to be moved, felt pulse and all.”

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Beloved is of the first hybrids that so moved me that I ventured from writing only poems to writing prose. The book is written in a variety of voices and fragmentary monologues, some of which are ambiguous. Beloved is a ghost story based on a true story, written in some of the most beautiful language I’d ever encountered.

Jane Ciabattari: Morrison draws upon gothic, fantastic, even romance genres, seizing the freedom to tell her story in ways that are, as she’s written, “outside most of the formal constructs of the novel.” Which sections do you consider most boundary-defying?

Peg Alford Pursell: In Beloved everything works together, of course, but what I’m most drawn to are those passages that might be termed discursive, in the best sense of the word. For example, Paul D, Sethe, and Denver set off for the carnival (on coloreds day) and we accompany them on the walk there, observing their actions and interactions with one another and with other “coloredpeople” along the way. We’re treated to an amazing image of the three’s shadows holding hands, though the characters are not themselves holding hands. Then Morrison writes of roses and the scent of their dying:

“Up and down the lumberyard fence old roses were dying. The sawyer who had planted them twelve years ago to give his workplace a friendly feel—something to take the sin out of slicing trees for a living—was amazed by their abundance; how rapidly they crawled all over the stake-and-post fence that separated the lumberyard from the open field next to it where homeless men slept, children ran and, once a year, carnival people pitched tents. The closer the roses got to death, the louder their scent, and everybody who attended the carnival associated it with the stench of the rotten roses.”

A more conventional novel wouldn’t likely contain this section about the state of the roses, how they came to be planted or why, or the particulars about how the open field is typically used and by whom. I can imagine an editor suggesting that such a passage be cut, or at least reduced to “relevant” sensory details.

Speedboat by Renata Adler

A now classic published in the 1970s, this book distilled the novel to its essentials. Which is to say paragraphs, with the cohesiveness of voice (that of the narrator, journalist Jen Fain), which investigates contemporary life (of that time period). The voice is wry, ambivalent, disaffected, hilarious. This book doesn’t let one get away with surface reading.

JC: Adler’s sentences and paragraphs are snakelike, twisting and ending up in surprising places. Like this: “Writers drink. Writers rant. Writers phone. Writers sleep. I have met very few writers who write at all.” Or this: “Maybe there are stories, even, like solitaire or canasta; they are shuffled and dealt, then they do or they do not come out. Or the deck falls on the floor. Or a piece of country music, a quartet, a parade, the flag—all the things one ought by now to be too old for—touch, whatever it is.” How do you think she keeps this voice so flexible?

PAP: Adler’s novel offers a stylistic nimbleness that I imagine evidences thoughtful revision and editing. At least it makes me feel better to believe that. The tone has been referred to as a restrained elegance of style, and tone is often achieved or certainly enhanced through careful attention to language. But more importantly is the nimbleness of the mind behind the book. The voice seems clearly to reflect the thinking of the author, her world view, and her interest in reflecting on the socio-political culture of the times she lived, rather than reflecting on the character alone. That voice flows between observations of small things, of life’s absurdities back to the narrator who’s doing the observing, to her heightened awareness, which, in turn, is the heightened awareness of the author herself. A nuanced sense of the narrator seeking answers underlies the jaded eye that creates a rich, authentic irony—and, I feel compelled to say, that irony is what constitutes the dramatic tension of the book.

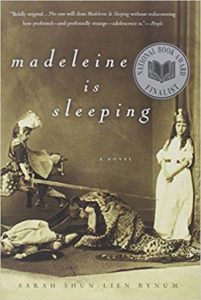

Madeleine Is Sleeping by Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum

In this novel-in-flash-fictions happenings shift between reality and illusion so that the reader is never quite certain what is “really” taking place. But with the fantastical characters that make up this fairy tale/fable/bildungsroman, that’s perhaps to be expected. I’m drawn to the structure of this novel segmented into very short flash fictions—or, arguably, prose poems as defined by their lyricism and poetic density—sometimes only a sentence long, none more than a page and a half. Bonus: each section is titled. I love to see an author make use of the convention of titling in unconventional ways (as in Mary Robison’s Why Did I Ever, for example) Here’s one section from Madeleine Is Sleeping:

in the candlelight

Louder, the widow says, leaning forward in her chair.

JC: How have the Bynum novel-in-flash (and the Robison, for that matter—a novel made of of 536 sections of a few sentences to a paragraph) influenced the structure and atmosphere of A Girl Goes into the Forest, with its 78 hybrid stories and fables?

PAP: It’s not always easy to see “influences” in one’s own writing. Certainly, A Girl Goes into the Forest contains very short stories or hybrids that straddle the line between fiction and poetry—prose poetry—like Bynum’s book (as well as other hybrid forms). Like both the Bynum and Robison books, titles matter. The narratives in both are compressed to their bones, and give so much space to the reader. I experience that space as a gift, allowing me to make my connections. And because I’m not told how to feel, the emotional experience is heightened. Similarly, in my book with its compressed narratives, I aim for that generosity, leaving enough room for the reader to engage, to dig in and create their own connections.

Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations by Mira Jacob

Nominally, this book has been called a graphic memoir. But what is notable is the elevation of the conversations as “story,” primarily the main conversation between Mira Jacob and her six-year-old half-Indian, half-Jewish son. Z wants to understand, as a child does, the nature of the culture he lives in: “Is it bad to be brown?” “Are white people afraid of brown people?” These innocent, essential questions are heartbreaking in their asking, in their answering (in Jacob delving into her past to unearth answers), in their living-out within the interracial family—what about Z’s own father: was he ever scared of brown people (like him)? The visual technique of cut-out characters collaged onto settings—often found photographs—those characters with unchanging facial expressions, tell the story, too.

JC: Jacob’s her son’s fresh experience brings her a dual vision of where we are now in this country. She writes, “Every question Z asked made me realize the growing gap between the America I’d been raised to believe in and the one rising fast all around us.” Her use of images makes the story of divisions among her own family members and in-laws less argumentative, more loving in some way. Does that make sense?

PAP: That’s a great observation, one I hadn’t considered. But now that you bring it up, I agree. She uses images of family members with unchanging facial expressions, so with that kind of neutrality, it’s up to the readers to determine from the words the characters’ emotions in the situations and the specifics Jacob portrays. I’m thinking, for example, of the part when Jacob’s character is present at her mother-in-law’s party (a bark mitzvah for her dog), and the guests—her mother-in-law’s friends from the dog park—assume that Jacob is the help because of her race, one that her mother-in-law doesn’t share. Jacob is pregnant at the time with her son Z., whose real life questions about race after the 2016 election served as the impetus of the book. The two have an interaction after the party ends, with the mother-in-law disbelieving that Jacob had been seen as the help. I found that scene so deftly conveyed, so powerful and poignant because of the well-chosen dialogue combined with the images of the two women with their neutral facial expressions. The readers project what they want and need to project onto the images of the characters in each given scene.

Mother Winter by Sophia Shalmiyev

Mother Winter is labeled as memoir, but it’s no less a collage of feminist manifesto accompanied with a soundtrack of information from Cezanne to Audre Lorde to Bernadette Mayer, to name but a few, and interwoven with meditations on motherhood, loss, displacement, transformation. Lyrical, sensuous, fiercely intelligent. She synthesizes the personal and the factual, offering insight and knowledge or learning.

JC: I’m struck by the ways she structures the book, like memory, sometimes telling the deepest, most powerful stories last. This makes sense, as she retraces her steps back to Russia to search for the mother who wasn’t a mother before her father took her away to the U.S.. And the language: “She was a pantry moth mother. Stuck mottled in sacks of grain. Everyone, encumbered, tattle-telling the truth about her. Trying to clean her out of their dark winter closets. A nuisance.” Do you have favorite lines?

PAP: I’m in love with the voice and the language in this book, the mind that burns through. I could quote line after line. I admire how Shalmiyev continually weaves into the narrative scientific data, facts and information about the natural world—it thrills me when a book provides knowledge as a matter of course. Shalmiyev is a genius in how she offers information that itself illustrates and furthers the narration. For example:

“We all have a propensity for false pattern recognition, to look for meaning, a belief system when mystery is too anxious of a box to contain us—a story that can signify a completeness we have only felt in the darkness of our mother.

‘We are dead stars looking back up at the sky,’ confirms the astronomer Dr. Michelle Thaller.”

But she’s also reminding me that we are 4 percent of what’s left after the last mass extinction …

We can only observe about four thousand stars in our night sky, but stardust collected in a jar will never make us a new planet. It is the loose bits of heat and gravity that create universes out there in the celestial wilderness, the feral, weightless darkness. But our survival depends on reading patterns, on following maps and having a guide, a compass, a cataloged history that we believe will help us predict disasters.”