Our quintet of quality this week includes Judith Butler on Bari Weiss’ controversial guide to fighting antisemitism, Hanif Abdurraqib on Ta-Nehisi Coates’ magical realist debut novel, Heller McAlpin on Leslie Jamison’s intriguing new essay collection, Rumaan Alam on Ben Lerner’s 90s-set autofictional latest, and James Lasdun on Kevin Barry’s melancholy gangster tale.

“She repeats her urgent pleas for the reader to wake up and avert a recurrence of a nightmarish history. At the same time, she does not take up the issues that make the matter so vexed for those who oppose both antisemitism and the unjust policies of the Israeli state. To do that, she would have had to provide a history of antisemitism, and account for the relatively recent emergence of the view that to criticize Israel is itself antisemitic. To fight antisemitism we have to know what it is, how best to identify its forms, and how to devise strategies for rooting it out. The book falters precisely because it refuses to do so. Instead, it elides a number of ethical and historical questions, suggesting that we are meant to feel enraged opposition to antisemitism at the expense of understanding it … if two things can both be true at once, shouldn’t we be able to think through the paradox of a dispossessed population gaining sanctuary only through the dispossession of another population? … What Weiss refuses to tackle is this particular anguish at the heart of Jewish families, communities, and congregations throughout the diaspora and even within Israel, one that often tears at the heart of individual Jews overcome by a strong sense of the need for justice—frequently derived from Jewish ethics—that compels them to distinguish their Judaism from prevailing forms of Zionism.”

–Judith Butler on Bari Weiss’ How to Fight Antisemitism (Jewish Currents)

“Throughout many corners of his writing, I have found Coates to be at his strongest when fully committing to his seemingly natural ability as an empathetic storyteller. This is most prominent in his long-form nonfiction work, where he is often able to seamlessly zoom out to tie his personal investments to broader social concerns. Because The Water Dancer is told in Hiram’s voice, through consistently unfurling memories and scenes, the emotional stakes of the book and its narrative/narrator feel immediate. The best work Coates does here is putting a reader in a position to connect to the jarring impacts of Hiram’s powers … In all of his work, Coates is strongly tied to allowing history to do heavy lifting, but the way history is woven into the fantasy world of this particular novel isn’t always as dazzling as the fantasy itself … There’s a tenderness not only in the language and story arc, not only in the frantic desires of Hiram and his need to belong, but especially in how gently the novel treats a person’s relationship with memory—and the parts of memory that don’t return as clearly as a person needs them to.”

–Hanif Abdurraqib on Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Water Dancer (4Columns)

“Jamison makes no claims to objectivity in her reporting. Quite the contrary. An overarching concern in Make It Scream, Make It Burn is with ‘the fantasy of objectivity.’ Even when reporting on a blue whale whose unusual song becomes a rallying cry for lonely people, or a family invested in the idea that their toddler’s nightmares channel his previous life as a pilot shot down by the Japanese in 1945, she investigates her own process and feelings with at least as much rigor as her research into the subjects themselves. Yes, this can lead to a self-involved form of meta-journalism. But the overall result is a heady hybrid of journalism, memoir, and criticism … Jamison has come a long way from the young woman who struggled to stave off loneliness with starvation and inebriation. In these tributes to what she has described as ‘the deep realms of enchantment lodged inside ordinary life,’ she shows—as she did in The Empathy Exams—that she’s not afraid to buck the trend toward ironic detachment, even at the risk of sentimentality. This is a writer who is incapable of being uninteresting.”

–Heller McAlpin on Leslie Jamison’s Make It Scream, Make It Burn (NPR)

“…in its concerns and structure, the novel is a departure, or maybe it’s a crisis of faith. It’s recognizably Lerner’s work, but its aims are different. His previous books depicted an engagement with a broadly liberal politics, mostly as a window into psychology or social taxonomy. In Topeka, the author aims for real insight into the current political moment. And Lerner attempts this via plot, never of much interest to him up to now. Yes, this is the story of our old friend Adam Gordon, but Lerner wants us to understand it’s also the story of the country in which we live … Lerner’s fiction has always carried political critique—of capital, war, climate change, technology; think of the hurricane that serves as a backdrop to 10:04 or the 2004 Madrid bombings at the center of the largely plotless Atocha. In this book, though, politics become something closer to the subject … I cannot answer why Lerner would bother with Trump at all. It is maybe a bid for significance, an attempt to show that autofiction, too, can manage social critique. And surely some readers will feel that The Topeka School does that successfully. It’s admittedly a very small matter, but: I am saddened by this book’s concerns more than by the book itself. Do we now need to add literary fiction to the long list of things Donald Trump has ruined? … Lerner is a masterful writer, but the politics of the moment are so baffling and strange that I wonder if any novelist could truly grapple with them.”

–Rumaan Alam on Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School (The New Republic)

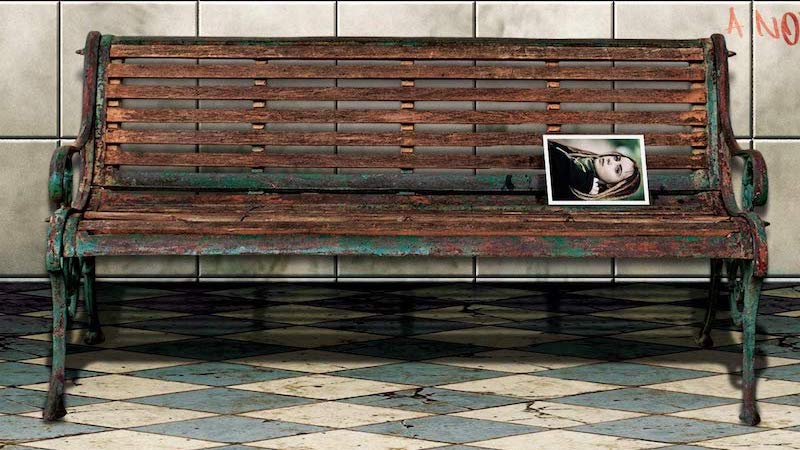

“In the desolate ferry terminal of the Spanish port of Algeciras, two battered old Irish drug smugglers, Maurice Hearne and Charlie Redmond, await the appearance of Dilly Hearne, Maurice’s long-vanished daughter, rumored to be traveling that night between Algeciras and Tangier. As they wait they drink, hand out fliers describing the missing young woman, attempt to menace or charm other passengers and trade melancholy banter in the high-low style of philosophical clowns out of Beckett or Jez Butterworth. Above all, they reminisce, drifting back through their vivid lives as partners in crime, intimate friends and treacherous rivals … The detours have the nonlinear, emotion-drenched agility of memory, moving by association through powerfully evoked moments in tense bedrooms, piratical bars and dubious neighborhoods in Irish or Mediterranean cities. Barry has a great gift for getting the atmospheres of sketchy social hubs in a few phosphorescent lines, and much of the pleasure of the book is in being transported from one den of iniquity to another, effortlessly and at high speed. He also has a nice turn of phrase and, as befits the vaudeville origins of his two leads, seems to have scabrously witty dialogue (the best of it unquotable here) on tap. There isn’t much psychological or (God forbid) moral analysis, so if you like your dark deeds illuminated by Dostoyevskian insight this might not be the book for you. But the sheer lyric intensity with which it brings its variously warped and ruined souls into being will be more than enough for most readers. It certainly was for me.”

–James Lasdun on Kevin Barry’s Night Boat to Tangier (The New York Times Book Review)