Our vault of virtuoso reviews this week includes James Wolcott on Michael Mann and Meg Gardiner’s Heat 2, Leah Greenblatt on Tess Gunty’s The Rabbit Hutch, Rebecca Onion on Rick Emerson’s Unmask Alice, Rob Doyle on Emmanuel Carrère’s Yoga, and Namwali Serpell on Mohsin Hamid’s The Last White Man.

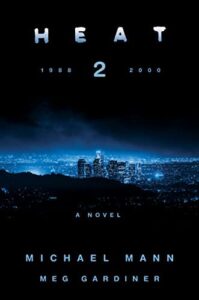

“Both a sequel and a prequel, Heat 2 expands the dimensions of the Manniverse, shifting the saga backward and forward in time, adding new passengers and disposing of fresh corpses. For those heathens and innocents who have never seen Heat, Mann and Gardiner provide a helpful prologue recapping the events of the film in dry Dragnet documentese … As in the original Heat, Heat 2 tees up intricately choreographed set pieces—a foiled home invasion (where would Mann’s oeuvre be without home invasions?), a daring raid on a cartel money house, a climactic shoot-out on the L.A. freeway—that play in the mind’s eye and pump the accelerator with mounting, marauding excitement, marvels of controlled chaos. The novel is nothing if not action-packed, a drive-in feature sandwiched between hard covers. Unfortunately, it is sometimes nothing but action-packed, a perpetual-motion collision machine manufacturing tension and suspense but offering no incidental moments of beauty, no lyric flourishes, just fine-tooled functionality … What I miss amid all the orchestrated mayhem is the mind-play and gamesmanship of true rivals … With McCauley dead at the outset of Heat 2, the runway lights of LAX having guided him to his eternal rest, a void is left for the role of worthy adversary, which is occupied and then some by a slab of meat named Otis Lloyd Wardell, a sadistic ogre whose calling card is burning women with cigarettes and impaling torture victims on hooks…Unmitigated evil isn’t interesting, even if it fills a big hole.”

–James Wolcott on Michael Mann and Meg Gardiner’s Heat 2 (AirMail)

“[There are] many bold moves in Gunty’s dense, prismatic and often mesmerizing debut, a novel of impressive scope and specificity that falters mostly when it works too hard to wedge its storytelling into some broader notion of Big Ideas … The Rabbit Hutch smartly reframes the depressing clichés of a vulnerable teenager and an older authority figure, in part by making them each so constantly aware of the roles they’re playing. One of the pleasures of the narrative is the way it luxuriates in language, all the rhythms and repetitions and seashell whorls of meaning to be extracted from the dull casings of everyday life. Gunty’s writing is so rich with texture and subtext it can sometimes tip over into the too-muchness of a decadent meal or a Paul Thomas Anderson film. As with many new novelists, and a lot of veteran ones too, her longer monologues tend to come off less like the cadences of ordinary speech than the workshopped thoughts of a star student … But she also has a way of pressing her thumb on the frailty and absurdity of being a person in the world; all the soft, secret needs and strange intimacies. The book’s best sentences—and there are heaps to choose from—ping with that recognition, even in the ordinary details … The Rabbit Hutch’s vibrant, messy sprawl can seem that way too, but its excesses also feel generous: defiant in the face of death, metaphysical exits or whatever comes next.”

–Leah Greenblatt on Tess Gunty’s The Rabbit Hutch (The New York Times Book Review)

“The grim idea that innocent kids may become addicts without ever taking a drug on purpose, victims of a cruel and unforgiving youth culture, has been embedded in American life for decades, and Go Ask Alice was foundational to it. It was also all made up. Rick Emerson’s new book Unmask Alice is a dogged unearthing, and attempted undoing, of all the falsehoods that went into the production of Alice … Sparks used two dozen entries from Alden’s diary and then added 190, ‘including all of the violent and occult material,’ Emerson notes. The result of this audacious fabrication was, for Alden’s family, catastrophic. They were ostracized in their town, and Alden’s gravestone was desecrated and stolen; the parents divorced, and the rest of the family scattered, leaving their community behind. There is a gothic quality to all of Sparks’ stories of teen ruin. If Sparks, who died in 2000, were alive today, she would find a welcome home in the QAnon-adjacent online community, producing some of its best underground-tunnel fan fiction … In Sparks’ world, teenagers—especially girls—are so fragile, they can basically implode upon contact with the world … Unmask Alice is more than the story of a (frankly) somewhat deranged older lady who let her imagination and ambition and self-righteousness run away with her…Books like Sparks’ speak to the darkest fears of parents whose kids’ minds and lives have become obscure to them.”

–Rebecca Onion on Rick Emerson’s Unmask Alice: LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries (Slate)

“…what makes it a Carrère book—and what makes me look forward to them so keenly— is his way of telling it, the trademark blend of extreme exhibitionism and digressive interest. His skill in constructing a narrative from disparate materials is exceptional, with all manner of insights, anecdotes and conjectures stacked up like hoops around the long slender ‘I’ … It’s not so much self-karaoke as self-cannibalism, with Carrère’s past work continually offering him a way forward … There is little point in accusing Carrère of vanity and narcissism when he is so upfront about these writerly vices, and yet he confesses to them so energetically that even the self-criticism comes to seem an aspect of that narcissism … The book’s ending on a rote—and, it seemed to me, delusive – note of hopefulness left me suspended in the ambivalence his books typically induce. Carrère’s body of work now strikes me as the product of a devil’s bargain wherein he keeps offering up everything, including his soul, to become a great writer—but even this, his becoming known as one who sacrificed it all for literature, is written into the fine print, a subclause in his diabolical vanity. All of which is not necessarily to denigrate what he’s doing. In a sense, his faintly sinister agenda is a testament to the resilience of the writer, of writing—a protective existential casing wherein even ardent pain can be rendered comfortable, can be material.”

–Rob Doyle on Emmanuel Carrère’s Yoga (The Observer)

“Tone above all distinguishes Hamid from these precursors. Whereas most of these writers bend race transformation toward satire, offering us topsy-turvy and hysterical tales, Hamid is deeply earnest about his conceit. The novel is that wan 21st-century banality, a ‘meditation,’ and it meditates on how losing whiteness is going to make white people feel. Mostly sad, as it turns out … The sex improves; the prose does not. A phrase from a later scene, ‘arousal shadowed by gloom,’ captures the general feeling. The novel evinces the worst of Hamid’s style … As in his earlier novels about social mobility and immigration, romance supplies the plot and casts an aura of ‘love’ over the politico-speculative gimmick. But Hamid here emphasizes the familial, perhaps as a stand-in for the genetic: The love between generations meets the idea that race is an inherited trait … What exactly is being born—or rather, borne? Darkness in The Last White Man is an ordeal. Those who were already dark have little presence and no internal life in the novel … The Last White Man in this way dramatizes the inane, paranoiac interpretation of migration known as the ‘Great Replacement,’ which was just condemned in a 2022 resolution by the U.S. House of Representatives … If Hamid’s novel were a self-aware satire of this ideology of whiteness and its violent effects, it would be pitch-perfect. But The Last White Man’s structure affords us no way to know if this is what Hamid intends: It includes no higher judgment, no specific history, no novelistic frame against which to measure the reliability of the narration, no backdrop across which irony can dance … The Last White Man feels like a primer for mourning whiteness, not a critique of it.”

–Namwali Serpell on Mohsin Hamid’s The Last White Man (The Atlantic)