This week’s Fantastic Five includes Ron Charles on Téa Obreht’s reimagined western, Angela Flournoy on Sarah Broom’s New Orleans-set family memoir, Sloane Crosley on Olga Tokarczuk’s philosophical fairy tale about life and death, Terrance Rafferty on Edna O’Brien’s harrowing Nigeria-set novel, and Craig Morgan Teicher on Poet Laureate Joy Harjo’s new collection.

“In this country, Obreht has found soil just as fertile for the propagation of myth and the complications of cruelty … It’s a voyage of hilarious and harrowing adventures, told in the irresistible voice of a restless, superstitious man determined to live right but tormented by his past. At times, it feels as though Obreht has managed to track down Huck Finn years after he lit out for the Territory and found him riding a camel. She has such a perfectly tuned ear for the simple poetry of Lurie’s vision … On the day we meet her, Nora has run out of water—a calamity that Obreht conveys with such visceral realism that each copy of Inland should come with its own canteen … The unsettling haze between fact and fantasy in Inland is not just a literary effect of Obreht’s gorgeous prose; it’s an uncanny representation of the indeterminate nature of life in this place of brutal geography … Sip slowly, make it last.”

–Ron Charles on Téa Obreht’s Inland (The Washington Post)

“…[an] extraordinary, engrossing debut … Broom…pushes past the baseline expectations of memoir as a genre to create an entertaining and inventive amalgamation of literary forms. Part oral history, part urban history, part celebration of a bygone way of life, The Yellow House is a full indictment of the greed, discrimination, indifference and poor city planning that led her family’s home to be wiped off the map. It is an instantly essential text, examining the past, present and possible future of the city of New Orleans, and of America writ large … Broom is our guide, but not the sort who holds readers’ hands, uninterested as she is in tidy transitions between one type of writing and another. The through line is her thought process, her frequent questioning … The interviews also yield unforgettable scenes … The true test of her worthiness is her empathy and focused attention. She is a responsible historian, granting her subjects the grace of multiple examinations over the years … Broom’s deadpan humor comes through clearest in her descriptions of herself … The Yellow House is a book that triumphs much as a jazz parade does: by coming loose when necessary, its parts sashaying independently down the street, but righting itself just in the nick of time, and teaching you a new way of enjoying it in the process.”

–Angela Flournoy on Sarah M. Broom’s The Yellow House (The New York Times Book Review)

“In Girl she even makes the daring choice to tell this terrible tale in the protagonist’s own words—an 88-year-old Irish woman speaking in the voice of a barely pubescent Nigerian girl … That choice feels natural because, despite the obvious contrasts in circumstances, this girl isn’t so different from O’Brien’s young Irish heroines. She lives in a world that’s testing her, daring her to survive. And she survives, in part, by the act of writing about her ordeals. In a scrupulously hidden diary, she enters the stark details of what she endures, records the nightmares she has while sleeping and awake … Girl isn’t the book to read for the history of Boko Haram and its long assault on the peaceful citizens of Nigeria, or for a nuanced analysis of the country’s volatile politics…Girl is the book to read for the sights and sounds and, yes, smells of some Nigerians’ harrowing experiences, and for a general sense of what it’s like to live in a world of radical, deadly unpredictability. Everything in Girl seems to happen suddenly, out of the blue or in the darkness of deep night. The novel hurtles, as its heroine is hurtled, from one thing to another and another and another, with deranging, near-hallucinatory speed … The violence is awful, but just as awful, in a way, is the day-to-day accommodation to relentless illogic and unreason—the creeping sense, at every moment, of certain disruption and displacement, sudden exile and loss. Girl captures that sort of existential dread as well as any war novel I know … O’Brien’s understanding of, and sympathy for, girls in trouble transcends culture—the place she’s made for them in her fiction is practically a country of its own.”

–Terrence Rafferty on Edna O’Brien’s Girl (The Atlantic)

“… marvelously weird and fablelike … Tokarczuk is a vocal feminist writer and it’s no accident that the more Duszejko’s sanity is called into question, the more relatable her plight becomes … Authors with Tokarczuk’s vending machine of phrasing and gimlet eye for human behavior (her tone is reminiscent of Rachel Cusk, with an added penchant for comedy) are rarely also masters of pacing and suspense. But even as Tokarczuk sticks landing after landing, her asides are never desultory or a liability. They are more like little cuts—quick, exacting and purposefully belated in their bleeding. If Flights,translated by Jennifer Croft, was built for ambience, Lloyd-Jones’s translation of Drive Your Plow was built for speed … Only the extended passages on astrology threaten to derail the reader. Lyrical as they are, they could be airlifted out of the novel without causing any structural damage. Tokarczuk successfully aligns these pages with the book’s broader themes, but one can feel that argument being made. Like an insurance policy against skimming … This book is not a mere whodunit: It’s a philosophical fairy tale about life and death that’s been trying to spill its secrets. Secrets that, if you’ve kept your ear to the ground, you knew in your bones all along.”

–Sloane Crosley on Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (The New York Times Book Review)

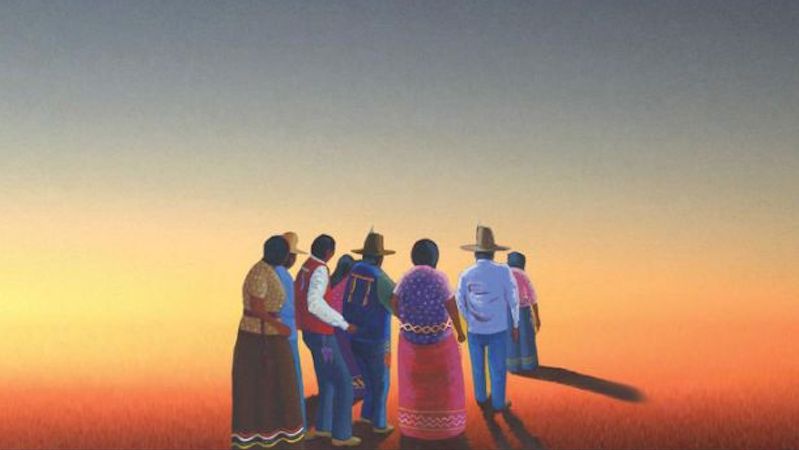

“While I do not believe that Joy Harjo’s recent appointment to the laureateship was intended as an explicit rebuke to President Trump, the poetry in her new book, An American Sunrise, casts an undeniably critical eye on the kinds of policies—and people—Trump tends to support. The first Native American to hold the laureateship, Harjo recalls and laments the violence and displacement that has marked hundreds of years of Native American history: ‘The children were stolen from these beloved lands by the government./ … / …they were lined up to sleep alone in their army-issued cages.’ She’s talking about Native American children forced from their homes in the 19th century, but it’s hard to imagine she does not also mean to call to mind the present horrors at the Southern border … Her poems are accessible and easy to read, but making them no less penetrating and powerful, spoken from a deep and timeless source of compassion for all—but also from a very specific and justified well of anger … a stark reminder of what poetry is for and what it can do: how it can hold contradictory truths in mind, how it keeps the things we ought not to forget alive and present.”

–Craig Morgan Teicher on Joy Harjo’s An American Sunrise (NPR)