Our basket of brilliant reviews this week includes Christopher Bollen on Dwyer Murphy’s An Honest Living, Huda Awan on Ottessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona, Jonah Bromwich on Zain Khalid’s Brother Alive, Laura Miller on Jerrett Kobek’s How to Find Zodiac, and Becca Rothfeld on Lillian Fishman’s Acts of Service.

“Murphy’s lonely, misanthropic narrator [is] fitted with the soul of a poet and the ethics of a dice thrower…Following the rules of the noir genre, the would-be detective is ruled by the stars of pride and lust, determined to discover who duped him even as he finds himself inexplicably drawn to an enigmatic femme fatale, the real wife … As with Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, the title of this novel is a joke—there’s no such thing as an honest living. Everyone is trying to game the system and skim as much off the top as possible … It is precisely style and atmosphere that give An Honest Living so much electricity and dimension. Like the best noir practitioners, Murphy uses the mystery as scaffolding to assemble a world of fallen dreams and doom-bitten characters … The novel is set in the mid-aughts, when BlackBerrys, Chelsea flea markets and the rougher edges of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, still existed. Murphy’s hard-boiled rendering of the city is nothing short of exquisite. It’s a landscape of reeking garbage, of salty rain sweeping off the ocean, of Midtown towers that look ‘ghostly like a mountain range,’ of 24-hour diners and warehouse parties, and of tiny, oddball delights, like discursions on bagel shops or the slowness of the G train, or when the narrator looks through a brownstone window to watch a middle-aged man try on 10 different bathrobes. For anyone who wants a portrait of this New York, few recent books have conjured it so vividly. For those who demand a straightforward mystery without any humor, romance and ambience, well, forget it, Jake, it’s literature.”

–Christopher Bollen on Dwyer Murphy’s An Honest Living (The New York Times Book Review)

“If readers of Moshfegh’s previous work have found those narrators sympathetic despite their unlikability, it is because they are given clues or back stories that account for their profound reclusiveness. In Lapvona, back stories are given, then resolutely undermined, sometimes in the same paragraph … Both authors assume a godlike position over their characters: Nabokov, like a chess master, manipulates his characters like pawns on a board; Moshfegh, like an entomologist, inspects her specimens so thoroughly that nothing is left unknown. The idea of an inaccessible and unbearable truth undergirds both novels, but how these authors treat and reveal these respective truths could not be more different. The narrative tricks Nabokov employs to withhold clarity are ingeniously crafty, while the bluntness of Moshfegh’s narration is more insidious. Lapvona is, in the end, hell-bent against surprise—what pulls the reader through the narrative in place of elegant or intricate crafting is the utter spectacle of debasement. At some points the violence is so over the top, so ridiculous, that one truly can’t help but laugh … With Lapvona, Moshfegh brings this project to its damning endpoint: the novel itself is revealed to be largely beside the point, its readers stupid for reading it … Moshfegh ought to be commended for departing from her usual first-person mode, but her newfound omniscience falls flat without the attendant sense of heartbreak that the best works of literature leave us with. A glimpse of the gutter would unnerve the best of us, but falling into it, fully, ought to devastate. Lapvona leaves the reader cold.”

–Huda Awan on Ottessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona (The Baffler)

“… feels like the first since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic that captures the mood of New York right now, describing a wounded city where, rather than holding on to what’s gone, residents are eager to rid themselves of the recent past … a book of ideas, a book of fathers and sons, a magical-realist mystery, and a revenge story … Earth’s mightiest heroes often make their homes in New York, and the brothers, with their preternatural talents, leap off the book’s pages. With the gift of gab in multiple languages, Dayo embodies the city’s quest for wealth … isn’t all darkness. Its cynicism is countered by the incredible warmth with which Khalid writes about his city … Its contradictions make it glow. It’s thick with ideas, imagination, wordplay, name-dropping, notable NYC cameos (Argosy! The 13th Step!), and casual acts of writerly daring, which occasionally go overboard. Read it with a pen and you’ll expend more ink than a zealous NSA redactor … This book, so focused on the past, sometimes seems to have little optimism for the future. But some of Khalid’s best writing comes when he has Youssef wax eloquent about whatever’s on the horizon. Even though Brother Alive is far from hopeful, wrestling with intellectual and political energies that seem to have no appropriate outlet, Youssef, and his author, maintain a sense of delirious wonder throughout. It’s a very New York quality: Every so often, the cynicism falls away and the sentiment—the affection that keeps us in this worn-out city—shines through.”

–Jonah Bromwich on Zain Khalid’s Brother Alive (The Atlantic)

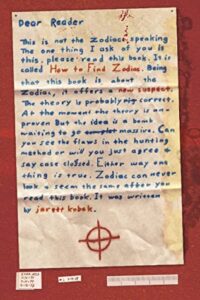

“I don’t find Kobek’s case for Doerr as Zodiac to be convincing. It’s an argument rife with confirmation bias and the dubious elision of such details as the Zodiac-brand watch found in possession of the San Francisco Police Department’s prime suspect, the face of which prominently features a crosshairs logo. But I still found How to Find Zodiac a fascinating portrait of a certain milieu and the people who populated it, hovering awkwardly between the establishment and the counterculture, attracted to the latter by tawdry fantasies of ‘free love’ but resentful of political change and any other perceived diminishment of their own status. Doerr was perfectly capable of railing against both the government and flag burners. Guys like him were everywhere, not nearly as rare as Kobek seems to think. Speculation about Zodiac suspects, taken all together, amounts to a bestiary of the seemingly countless creepy men of late ’60s Northern California. Along the way, How to Find Zodiac unearths a few nonsuspects of the same ilk … Does he see something of himself in Doerr, a writer forever struggling to be heard? I’ll confess to seeing a bit of myself—a critic—in Kobek, who offers something a lot like literary criticism as an alternative to forensics: nail down someone with tastes, influences, and interests identical to Zodiac’s, and you’ve got Zodiac. I think that’s one reason why the Zodiac case still exerts such an enduring fascination. He got away with his crimes, leaving the world with a sparse collection of clues—an oeuvre of sorts, one we polish and polish until it presents us with a reflection of our communities, our fathers, ourselves.”

–Laura Miller on Jerrett Kobek’s How to Find Zodiac (Slate)

“‘I’d always believed that sex masterpieces were the best kind. Better than Bach, the Empire State Building or Marcel Proust,’ writes the novelist and memoirist Eve Babitz in her classic of 1960s and 70s LA, Slow Days, Fast Company. Lately it seems as though sex masterpieces may be endangered. More and more we are told that sex is about everything but sex itself…For commentators on both the left and the right, sex has become a problem to be solved. It is rarely recognised as a potential masterpiece … Thankfully, there are still a few sex-artists among us, and they are beginning to assert themselves. One of the most exciting is Lillian Fishman. ‘My art is fucking,’ says Nathan, a character in her extraordinary debut novel, Acts of Service, a work of ferocious moral and sensual intelligence and a masterly defence of sex for its own sake … At first glance, it seems as though Acts of Service stages a contest between Eve’s sensuality and her scruples. Desire is quite literally put on trial when Nathan is accused of workplace harassment and Eve is called on to give evidence. But, in fact, Fishman’s elegant novel ventures an alternative sexual ethic, one unconstrained by conventions but nonetheless fiercely attentive to what we owe one another … The implication is as bold as it is urgent: it is that sex, unencumbered by romance or obligation, is itself sufficient to move and remake us. In an age of resurgent puritanism, Acts of Service is a rare and much-needed sex masterpiece.”

–Becca Rothfeld on Lillian Fishman’s Acts of Service (The Guardian)