This week’s quintet of quality reviews includes Laura Marsh on Curtis Sittenfeld’s Rodham, Catherine Lacey on Kate Zambreno’s Drifts, Gary Indiana on Blake Gopnik’s Warhol, Jess Bergman on Anna Wiener’s Uncanny Valley, and Claire Messud on Maggie Dherty’s The Equivalents.

“More than any other politician of recent years, Hillary Clinton has served as a way of glimpsing what might have been … the way the novel arrives at a Hillary presidency is an unexpectedly tangled one. It is not the story of a woman shorn of a problematic man and finally able to shine. Rather than a fantasy of Hillary’s potential fulfilled, it reimagines major parts of her character, removing from her any of the major flaws or contradictions that could hamper a politician in the MeToo era. Perhaps the strangest aspect of Rodham is that in crafting an exemplary version of Hillary Clinton, the book—apparently unwittingly—presents a harsh critique of the person we know today … This is the novel’s third big counterfactual: What if Hillary Clinton had chosen to believe a victim of sexual assault over loyalty to the man she loved? The fictional Hillary’s clarity on the question allows Sittenfeld to imagine the glories of her political ascendancy, but it doesn’t connect back to the actually existing Hillary Clinton very smoothly … Perhaps a bigger problem for the book as a work of fiction is its trouble imagining just how Hillary Rodham would have turned out absent the privileges and the traumas of her time as first lady and her decades at the very top level of American politics and global power … What makes this version of Hillary run? Without a guiding philosophy, Senator Rodham turns out to be a surreal composite of women in politics … Sanders’s absence reveals a larger weakness of Rodham, which is its curiously limited view of what is at stake in American politics today. Not only is there no rising democratic social movement on the margins of this novel, it’s as if the 2008 crisis and Great Recession never happened.”

–Laura Marsh on Curtis Sittenfeld’s Rodham (The New Republic)

“Like many of the writers she resembles or reveres—Jean Rhys and Robert Walser, to name an odd pair—Zambreno draws on autobiography but never leans on it. Her narrators are prone to quoting Barthes or Sontag or deconstructing art-house cinema, but her sentences are always airy and streamlined, full of wit and candor … ‘Drifts is my fantasy of a memoir about nothing,’ the narrator says. ‘I desire to be drained of the personal. To not give myself away.’ (I’m still unsure whether she gives herself away when she confesses, ‘I masturbate throughout the day, so much that I pull a muscle in my writing hand, which makes me feel like Robert Walser.’) … Drifts, like much of Zambreno’s work, mourns the great writers of the past and yawns at a publishing culture in which ‘a prominent writer of so-called autofiction, with a half-million-dollar advance on his last book, wins the so-called genius grant’ … I enjoy and admire Zambreno’s work so much that I resisted accepting that there is a flaw in this book: The structure of the narrative suggests that childbirth is the answer to every question she’s been asking, a necessary redemption from her existential woes … I would have welcomed a portrait of the mother masturbating herself into a Walser-y stupor between diaper changes, but I’m a little baffled that a book suspicious of tidy narratives seems to conclude on the healing powers of childbearing. Still, other readers may be reassured by the suggestion: that an artist will always be dissatisfied with her output, but parents will be enraptured with theirs.”

–Catherine Lacey on Kate Zambreno’s Drifts (The New York Times Book Review)

“The extreme tension in Warhol’s work between meaning and non-meaning has to do with random gestures, accidents, and visual noise carrying as much weight as design. Likewise, a lot that happened in Warhol’s life just sort of happened, the way lots of things happen in every life. This obvious fact, and much else that would occur to most sentient beings, has entirely eluded Blake Gopnik, whose elephantine, ill-written, nearly insensible Warhol has now been unleashed, weighing in at nine hundred pages, any of which suggests nothing so much as an incredibly prolonged, masturbatory trance of graphomania … None of this effort has produced anything resembling a fresh idea. Information that has been available for decades is rolled out as startling news, embedded in a dense lard of fatuous pedantry and vapid generalizations. Gopnik’s writing generally reads like boilerplate cribbed from bygone reviews and magazine articles, recast in a squirmy, sophomoric prose that deadens everything it touches … Gopnik’s ideal reader is someone who has never read a word about Warhol or contemporary art, seen a movie, or formed two consecutive thoughts without assistance … Warhol would shrink to about twenty pages if he simply stated what happened and left it at that … This book could appear only at a time when the bohemian mobility, sexual freedom, and cultural ferment of New York in the Sixties, Seventies, and early Eighties are not simply being forgotten, as people who were there die off, but becoming unimaginable.

–Gary Indiana on Blake Gopnik’s Warhol (Harper’s)

“A stranger in a strange land, [Wiener] defamiliarizes the new norms of the tech industry unquestioningly swallowed by her peers, restoring friction to a milieu devoted to eliminating it … These salient details accrue like layers of paint, and ultimately the effect is impressionistic rather than schematic … Earlier this year, Wiener told an interviewer at The Guardian that she wants Uncanny Valley ‘to be politically useful,’ but that desire isn’t always borne out by the text. Wiener is an unsparing observer of tech-exacerbated gentrification, for example, but the unsettling images she conjures tend to be registered more than interrogated. The anecdotal approach can only take her so far, and occasionally it constrains the aperture of Uncanny Valley’s critique, leaving Wiener with little to say about aspects of the tech industry that have been rendered deliberately invisible, like its reliance on a permanent underclass of gig workers, or the scandalous conditions of the factories in which its thousand-dollar gadgets are made. This cloistered point of view can lead to shallow diagnoses … This oversimplification isn’t so much a failing of the book as a reflection of its form—ironic, perhaps, considering that Wiener’s choice of genre was influenced by that aforementioned political ambition…Though the book is nonfiction, Uncanny Valley is not a polemic; it’s a memoir with palpable literary aspirations, the strength of which rests largely on Wiener’s elegantly disaffected style. Her restraint proves incompatible with the prospect of a structural critique of the tech industry, which has done much worse than imbue our lives with the tinge of unreality … the quality of Wiener’s noticing yields pleasures far beyond the analytical. But there are moments that suggest she knows more than she’s letting on … It would have been interesting to see [Wiener] wrestle with everything the Valley gave her.

–Jess Bergman on Anna Wiener’s Uncanny Valley (Jewish Currents)

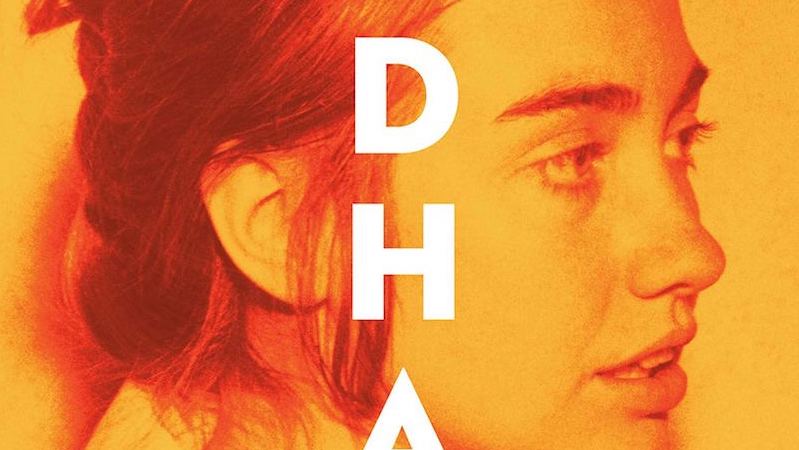

“Doherty provides lively glimpses of the individual trajectories and projects of these artists, both in the years leading up to and after their time at Radcliffe. Olsen’s complicated relationship with the academy is well evoked, as are Sexton’s volatility … Doherty may be less interested in the visual artists; or perhaps there exists less documentation of their thoughts and experiences … Doherty’s attention to these early Radcliffe fellows is tempered by her awareness of the institute’s homogeneity at the time with respect to race and, for the most part, class … This endeavor simultaneously to offer a broader context for the Radcliffe Institute and to cover a large period of time—from 1957 to the mid-1970s—ultimately renders The Equivalents somewhat diffuse, and in places it can feel skimpy. While Sexton’s and Kumin’s lives are thoroughly documented (and have been told elsewhere), Swan’s and Pineda’s in particular are only briefly handled. Doherty isn’t notably a stylist, and her descriptions can be perfunctory … It’s hard to tell whether the book’s primary interest lies in portraying the complicated and demanding friendships among Kumin, Sexton and Olsen in the context of what is now the Radcliffe Institute, or in representing, at speed, the diverse strands of feminist activism and scholarship in the late ’60s and ’70s. Doherty tries to address all of these, in part, one suspects, because the subjects of her title—the five ‘Equivalents’—seem, from a contemporary intersectional perspective, potentially problematic: They were white, and, with the exception of Olsen, educated and largely well-off … Doherty’s account, may have its flaws, but The Equivalents is nevertheless an illuminating contribution to our history.”

-Claire Messud on Maggie Doherty’s The Equivalents (The New York Times Book Review)