Our basket of brilliant reviews this week includes James Wood on Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun, Charles Yu on Stephen King’s Later, Christian Lorentzen on Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth, Jia Tolentino on Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind, and Adam Haslett on Russell Banks’ Foregone.

“… Klara and the Sun confirms one’s suspicion that the contemporary novel’s truest inheritor of Nabokovian estrangement—not to mention its best and deepest Martian—is Ishiguro … Never Let Me Go wrung a profound parable out of such questions: the embodied suggestion of that novel is that a free, long, human life is, in the end, just an unfree, short, cloned life. Klara and the Sun continues this meditation, powerfully and affectingly. Ishiguro uses his inhuman, all too human narrators to gaze upon the theological heft of our lives, and to call its bluff … Ishiguro keeps his eye on the human connection. Only Ishiguro, I think, would insist on grounding this speculative narrative so deeply in the ordinary; only he would add, to a description of a battle between sunlight and darkness … Whether our postcards are read by anyone has become the searching doubt of Ishiguro’s recent novels, in which this master, so utterly unlike his peers, goes about creating his ordinary, strange, godless allegories.”

–James Wood on Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun (The New Yorker)

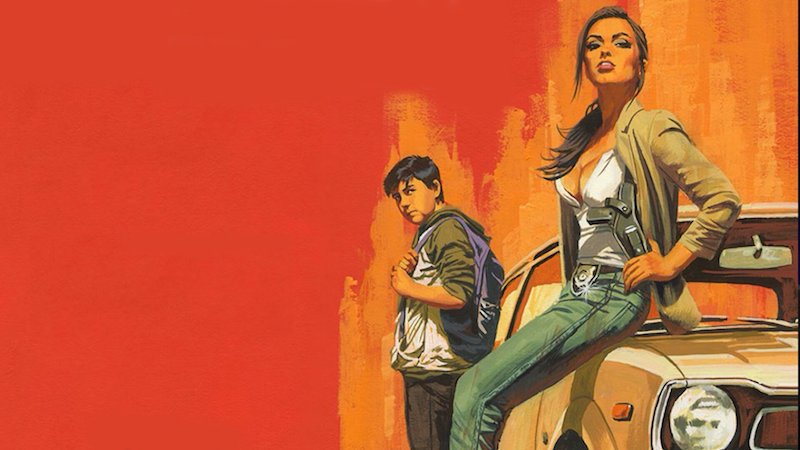

“In his craft memoir, On Writing, Stephen King describes a moment in his process when he asks himself the ‘Big Questions.’ The biggest of which are: ‘Is this story coherent? And if it is, what will turn coherence into a song?’ You can feel King reaching for some Big Questions in his most recent novel … The result is something of a genre hybrid: part detective tale, part thriller, with a horror story filling in the seams. And the horrors are many. There are hints of evil from another dimension, things from ‘outside the world’ and ‘outside of time.’ But mostly the horrors are familiar ones. Plain old human cruelty. The loss of loved ones to disease or old age. Alzheimer’s. Also, less morbid though no less heavy: the loss of innocence. Growing up too fast. The unexplainable, the incomprehensible in our everyday lives … From all of this, King weaves a story of adolescence with a sweetness at its heart—the touching and genuine relationship between Jamie and Tia. Therein lies the book’s strength…But this strength is also a liability. Despite its early assurance to the contrary, Later is like that movie with Bruce Willis.”

–Charles Yu on Stephen King’s Later (The New York Times Book Review)

“In the end there is only the careerist, the professional writer who is first, last, and only a professional writer. The original and so far ultimate careerist in American literature was Philip Roth … Roth had a persistent public-relations problem. Too often he was confused with his characters. Roth was never not a Jew, but his true creed was secular, his gods success and sex. He made his name writing about race traitors, class traitors, and perverts. He needed to spread the word that he was still a Nice Jewish Boy: responsible, successful, and normal. He was getting too much mail: hate mail from offended New Jersey rabbis and propositions from turned-on Midwestern nurses. He relished it all, but he knew as soon as he had anything that he had a lot to lose … An exquisitely managed career, right down to this totemic and compulsively readable biography, which young writers are well advised to consult as a blueprint for enduring literary stardom. Its lessons include: never marry; have no children; lawyer up early; keep tight control of your cover designs; listen to the critics while scorning them publicly; when it comes to publishers, follow the money; never give a minute to a hostile interviewer; avoid unflattering photographers; figure out what you’re good at and keep doing it, book after book, with just enough variation to keep them guessing; sell out your friends, sell out your family, sell out your lovers, and sell out yourself; keep going until every younger writer can be called your imitator; don’t stop until all your enemies are dead.”

–Christian Lorentzen on Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth (Bookforum)

“Consider Dorothy, the protagonist of Christine Smallwood’s jewel of a début novel … Like many of the people who will love this novel, Dorothy is either tremendously depressed and dysfunctional or completely ordinary and doing pretty well … Smallwood generates a bounty of humor from the chasm between the kind of things Dorothy thinks…and the kinds of things she does … Smallwood begins a sentence by writing, ‘I am not saying that the scholarly critical endeavor is a futile one, necessarily.’ This sentiment, extremely funny in [the] context [of Smallwood’s dissertation], is applied to even sharper effect in the novel, where scholarly critical endeavor is both Dorothy’s primary approach to understanding the world and the process by which she constantly dissociates from it … Smallwood’s casually agonized and abundantly satisfying novel…provides the exact sort of thrill that can be found only through obsessive overthinking. Why live in the moment when you can dissect it like this?”

–Jia Tolentino on Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind (The New Yorker)

“One of the main strands of Banks’s fiction has long been what you might call a working-class New England existentialism. In bitterly eloquent novels such as Affliction, The Sweet Hereafter and Continental Drift, he has chronicled the blunted, pragmatic affect of Northern white men and the women unfortunate enough to be entangled with them. Foregone is in the same vein, only here the protagonist is an artist. And what Banks reveals of this artist’s life is a profound emptiness … As always, Banks’s prose has remarkable force to it. Like Emma, the reader too might prefer that Fife stop torturing himself in public, indulging in what is at times a kind of baroque self-recrimination complete with the sexist presumptions of the postwar American male. But there is such brio in the writing, such propulsion as the lashes are applied, that we follow Fife into the depths. The book’s real theme is the curse of being convinced that one is unlovable. And who among us hasn’t suffered that conviction to one degree or another? … To his credit, Banks has never solicited his readers’ approval of his characters, and many are unlikely to be charmed by Leo Fife. But what they will find in Foregone is a character, a novel and a writer determined not to go gentle into that good night.”

–Adam Haslett on Russell Banks’ Foregone (The New York Times Book Review)