Climate change prophesies, fictionalized dispatches from the drug-war, and an unusual musician’s memoir are all under the critical spotlight this week.

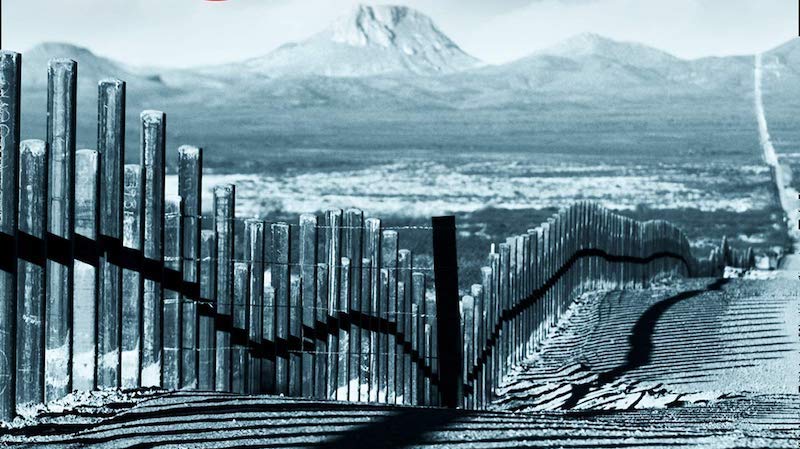

In her New York Times review of The Border—the final part of Don Winslow’s acclaimed drug-war trilogy—Janet Maslin calls the novel “devastating…a book for dark, rudderless times, an immersion into fear and chaos.”

Over at Slate, Susan Matthews considers David Wallace-Wells’ harrowing investigation into the cataclysmic ramifications of climate change, The Uninhabitable Earth. “In his attempt to explain how climate change will kill,” Matthews writes, “Wallace-Wells does a terrifyingly good job of moving between the specific and the abstract.”

Meanwhile, Vox‘s Constance Grady was deeply impressed by how Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman—in her memoir, Sounds Like Titanic—takes a wacky story about pretend violin playing and turns in into a meditation on gender, economy, and the attitudes of post-9/11 America.

We’ve also got Parul Sehgal of the New York Times on Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (“an exhilarating social history….[of] young black women ‘in open rebellion'”) and the New Yorker‘s Katy Waldman on Chloe Aridjjs’ Sea Monsters, a Sebaldian tale of a young Mexican woman who runs away to a beach community in Oaxaca (“self-contained, inscrutable, and weirdly captivating”).

*

“Of all the blows delivered by Don Winslow’s Cartel trilogy, none may be as devastating as the timing of The Border, its stunner of a conclusion … This is a book for dark, rudderless times, an immersion into fear and chaos. It conjures more lawlessness, dishonesty, conniving, brutality and power mania than both of the earlier books put together. Because of that chaos, it might have benefited from an indexed cast of characters. But Winslow can’t provide one. For one thing, it would be a spoiler. You just have to watch these miscreants as they drop … Winslow describes sting operations with immersive, heart-grabbing intensity. You don’t read these books; you live in them … Last and never least with Winslow: the matter of languages. He is fluent in many of them, and The Border once again shows off those talents … The border ends with another idea about the soul. ‘There is no wall that divides the human soul between its best impulses and its worst.’ Two classic trilogies, The Godfather and now this one, are built upon it.”

–Janet Maslin on Don Winslow’s The Border (The New York Times)

*

“Aridjis is deft at conjuring the teenage swooniness that apprehends meaning below every surface. Like Sebald’s or Cusk’s, her haunted writing patrols its own omissions … Sea Monsters largely consists of Luisa ‘zigzagging’ among beachcombers, nudists, and vagabonds; noting dogs and waves; and meditating on her past life in Roma, the district in Mexico City where she attended a fancy international school on a scholarship. (Most of her classmates had bodyguards.) She waits in vain for something amazing to happen in surroundings that tremble with potential … Sebaldian novels tend toward the paradoxical: they are hypnotic narratives about disenchantment. Something has broken the world, traumatizing the narrator and showering the reader in beguiling fragments. In Austerlitz, the trauma is the Holocaust. Sea Monsters gathers stray observations, bits of ocean treasure, but there is no obvious rupture to explain their suggestive sense of incompletion … The figure of the shipwreck looms large for Aridjis. It becomes a useful lens through which to see this book, which is self-contained, inscrutable, and weirdly captivating, like a salvaged object that wants to return to the sea.”

–Katy Waldman on Chloe Aridjjs’ Sea Monsters (The New Yorker)

*

“Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Saidiya Hartman’s exhilarating social history, begins at the cusp of the 20th century, with young black women ‘in open rebellion’ … Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments is a rich resurrection of a forgotten history, which is Hartman’s specialty. Her work has always examined the great erasures and silences—the lost and suppressed stories of the Middle Passage, of slavery and its long reverberations. Her rigor and restraint give her writing its distinctive electricity and tension. Hartman is a sleuth of the archive; she draws extensively from plantation documents, missionary tracts, whatever traces she can find—but she is vocal about the challenge of using such troubling documents, the risk one runs of reinscribing their authority. Similarly, she is keen to identify moments of defiance and joy in the lives of her subjects, but is wary of the ‘obscene’ project to revise history, to insist upon autonomy where there may have been only survival, ‘to make the narrative of defeat into an opportunity for celebration’ … This kind of beautiful, immersive narration exists for its own sake but it also counteracts the most common depictions of black urban life from this time—the frozen, coerced images, Hartman calls them, most commonly of mothers and children in cramped kitchens and bedrooms.”

–Parul Sehgal on Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (The New York Times)

*

“The bulk of the book is an expanded, horrifying assessment of what we might expect as a result of climate change if we don’t change course. The result is a frightening, compelling text that re-raises the question: In the face of existential threat, what role can storytelling hope to play? Wallace-Wells is an extremely adept storyteller, simultaneously urgent and humane despite the technical difficulty of his subject … The ultimate effect of all of this is to feel as if Wallace-Wells is scanning through the entire world with a sort of overactive bionic eye, zooming in on different problems, calculating the risk, and then zooming back out and over to something else … In his attempt to explain how climate change will kill, Wallace-Wells does a terrifyingly good job of moving between the specific and the abstract … But, as Wallace-Wells points out, 800 million people are already food insecure, and thousands of people drown in floods (and die of asthma, and heat stroke, and forest fires). For me, this frequent reminder of the current baseline was one of the scariest parts of the book. Time’s slippery slowness prevents us from ever fully internalizing how much has already been made worse by climate change … Through the Wallace-Wells climate change–focused lens, industrialized society is a tragedy in which we thought we had built something enduring while really, we had just exploited fossil fuels into a temporary mirage of an empire that would end up drowning the rest of the world … Still, his optimism feels hard to square with the preceding 200 pages of detailed disaster. Ultimately, what I’m left wondering is: Who is this book for, exactly? Wallace-Wells’ response to the critics who argued that he was unproductively scaring people was to correctly point out that there are way more people not alarmed enough about climate change than there are people who are too alarmed. The book, then, is for them. It will undeniably alarm them. What I can’t help but wish is that it also offered them a plan.”

–Susan Matthews on David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth (Slate)

*

“She isn’t just using her experience as a fake violinist as a wacky story. In her hands, it becomes the starting point for bigger issues. She explores questions about gender, and about how and why, as a young woman, she was only able to feel respected when she was playing her violin in front of a crowd. She explores questions about the economy, and how the student debt crisis drove her to keep working as a fake violinist even as it caused her to lose her grasp on the difference between fiction and reality. And more and more as the book goes on, Hindman delves into questions about America’s endless appetite for comforting fakery, and how that desire for comfort played out in the post-9/11 era and the runup to the Iraq War … What Hindman eventually concludes, though, is that America did not want explanation in the years after 9/11. America wanted soothing. And that’s what the violin tour she was faking working at had to offer: It gave the appearance of a live performance of a knockoff of a movie soundtrack about a historical tragedy. And in so doing, it ‘strengthened [Americans’] resolve to believe that even the most shocking national tragedy will evolve over time, become a story told by old women with good senses of humor.’ It was deliberately fake, and it was deliberately bland, and it was comforting.”

–Constance Grady on Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman’s Sounds Like Titanic (Vox)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.