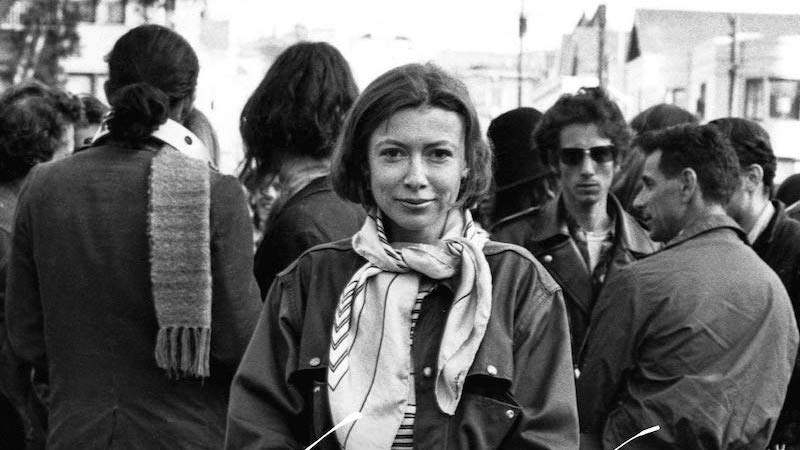

Our mighty five this week includes Hilton Als on Joan Didion’s early novels, Ryu Spaeth three liberal writers who rail against woke culture, Daniel Woodrell on The Complete Stories of Larry Brown, Scott Simon on Thomas Lynch’s musings on death, and Toby Lichtig on Ben Lerner’s autofiction.

“What no Didion heroine can entirely reconcile herself to is the split between what she wants and what a woman is supposed to do: marry, have children, and keep her marriage together, despite the inevitable philandering, despite her other hopes and dreams. Didion’s women have an image in mind of what life should look like—they’ve seen it in the fashion magazines—and they expect reality to follow suit. But it almost never does. In Didion’s fiction, the standard narratives of women’s lives are mangled, altered, and rewritten all the time. Play It as It Lays also centers on a woman failing to live up to social expectations, and it comes as close as any book has come to representing what repression does to the soul … To me, A Book of Common Prayer was feminist in the way that Toni Morrison’s Sula, published four years earlier, was feminist—without having to declare itself as such. But, whereas the two friends in Sula live inside their relationship, Didion wrote about a woman trying to enter into a friendship and a kind of love with another woman who is ultimately unknowable … A Book of Common Prayer is an act of journalistic reconstruction disguised as fiction: a Graham Greene story within a V. S. Naipaul novel, but told from a woman’s perspective, or two women’s perspectives, if you believe Charlotte, which you shouldn’t … Part of Didion’s genius was to make language out of the landscape she knew—the punishing terrain of California’s Central Valley, with its glaring hot summers and winter floods, its stark flatness, its river snakes, taciturn ranchers, and lurking danger. ‘Those extremes affect the way you deal with the world,’ she said in a 1977 interview. ‘It so happens that if you’re a writer the extremes show up. They don’t if you sell insurance.'”

–Hilton Als on Joan Didion’s early novels (The New Yorker)

“There is a certain kind of liberally inclined writer who sees Donald Trump’s America as a nation in crisis. At every turn, in every tweet, she is confronted by the signs of an ongoing catastrophe, from which it may be too late to escape. An ugly, vicious intolerance spread on social media; the collapse of norms once considered sacred; a crass narrow-mindedness surreally celebrated by some of this country’s most powerful institutions—these are all elements in the gathering storm of a new, distinctly American fascism. The twist is that this crisis has its source, she contends, not in the person of Trump, but in his frothing-mouthed opposition: the left … The foot-stamping insistence on individual rights obliterates what should be a tension between those rights and the well-being of the community as a whole. This is all the more relevant at a time when the political implications of unbridled individualism, represented by capitalism’s self-made man, have never been clearer. There must be a way to express oneself while also ensuring that others aren’t silenced, oppressed, and forgotten. There must be a way to protect the individual while addressing dire problems that can only be fixed collectively, from environmental collapse to systemic racism and sexism. To err on the side of solidarity, even against one’s strongest emotions, is not to sacrifice our individual humanity. It is to accept what Elizabeth Bennet finally learned: that the truth will set you free.”

–Ryu Spaeth on Bret Easton Ellis’ White, Megan Daum’s The Problem With Everything, and Wesley Yang’s The Souls of Yellow Folk (The New Republic)

“Brown, who died in 2004 at age 53, had the background and artistry that allowed him to fully inhabit the world of his characters. He knew the hidden details, and told vibrant, strangely funny stories featuring the grit and detritus of hardscrabble lives in the fetid South. The voice was plain, direct, quite often close to confessional, at other times clearly confessional. His heart was big and his arms spread wide. He didn’t look away from characters who had an obvious flaw, or a couple of them, maybe more, and they were never portrayed as less than human, beyond concern, unworthy souls. He challenged the reader to give a damn. His stories bring to mind John Steinbeck’s forgiving depictions of scamps and scoundrels in Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row, as both authors show great regard for sad-sack charmers stumbling along the sun-bleached road to wherever … The folks in Brown’s stories aren’t strivers. They don’t have ‘professional’ lives. They may worry a lot, but not about ways of altering their circumstances. It would be nice to pay a few bills, sure, but that can wait one more week; it’s hot outside and the taverns are cool. The major entertainments on display are hitting the sauce and the search for love, as love and all the tipsy complications provide the ongoing drama in these people’s lives.”

–Daniel Woodrell on The Complete Stories of Larry Brown (The New York Times Book Review)

“A lot of writers put life and death into their work. But for almost four decades, Thomas Lynch has examined what Auden called the ‘unmentionable odor of death,’ those details that even the most unflinching writers usually dodge. Lynch, also a poet, is at least as well known in his village of Milford, Mich., as a funeral director (Lynch & Sons, with six locations). Some of his finest, wryest and most stylish essays about the human enterprise of mortality appear together in this collection … When Lynch takes us into his later struggles with alcoholism and estrangement, you read them as the words of a man who has been bathed from birth to know how easily the gift of life can be rendered into dust … Lynch writes of Wesley Rice, an embalmer who worked 18 hours to restore the appearance of the head of a young girl who had been abducted, raped and beaten to death with a baseball bat. All of his effort was so that a single, suffering person—the girl’s mother—could see her daughter’s face at peace…By the time Lynch concludes, ‘What Wesley Rice did was a kindness,’ you may want to add ‘and a blessing.’ And you will be grateful for these graceful essays, which light up so many of the dark details that are part of what is, after all, the one demographic to which we will all belong.”

–Scott Simon on Thomas Lynch’s The Depositions (The New York Times)

“If one of The Topeka School’s many miracles is the way in which its proliferation of ideas are held in place, entwined, made to reinforce one another (Adam’s elegant address in one debate is described as ‘a circuit that amplifies the sense of coherence and closure’), then this exhilarating feeling of composed artistic plenty stands in contrast to the preoccupation with uncontrolled babble coursing through the novel. It isn’t just the shouty, mansplaining men, or the foaming fundamentalist Christians who slosh their abuse at Topeka’s liberals, or Adam and his young friend resorting to ‘some kind of mash-up of masculine gibberish’ when they square up to one another, or Adam’s ‘post-verbal’ grandfather dissolving into dementia in his care home. An anxiety about unstable language is everywhere apparent…One might reasonably ask at this point: and so what? Which Brooklyn novelist with glasses isn’t obsessed with the instability of language? But Lerner isn’t just offering a weary postmodern jeu d’esprit, shruggingly embracing the meaninglessness of it all. For the apprehension of nonsense, of unreason disguised as reason, is as central to the book’s political diagnosis as it is to its artistic purpose: unreason linked to violence, bad words to bad deeds.”

–Toby Lichtig on Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School (The Times Literary Supplement)