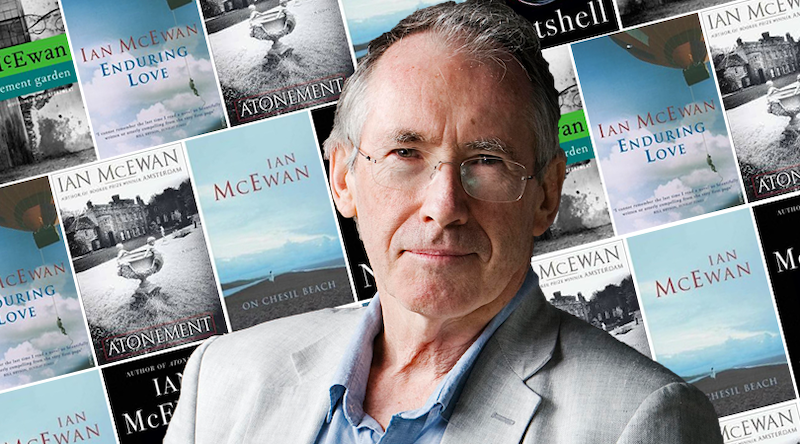

Machines Like Me, the fifteenth novel from Booker Prize-winning English author Ian McEwan, hit shelves earlier this week. A high-concept (though apparently not science fiction) novel set in an alternate 1980s—in which JFK is alive, the Beatles have regrouped, and the famed WWII-era mathematician and cryptanalyst Alan Turing becomes the face of the world’s computer revolution—it’s the story of a young London man who uses money left to him after his mother’s death to buy a first-generation A.I. android named Adam.

This foray into the speculative marks another interesting creative shift for McEwan, whose forty-year career has produced tales of the grotesque (Between the Sheets, The Cement Garden); Cold War-era espionage dramas (The Innocent, Black Dogs); cerebral psychological thrillers (Enduring Love, Amsterdam); metafictional literary blockbusters (Atonement); quietly devastating portraits of broken relationships (On Chesil Beach); domestic dramas infused with contemporary political concerns (Saturday, Solar); and even a darkly comic Shakespearean homage narrated by a fetus (Nutshell).

Unusually for a literary fiction writer, McEwan has also seen the majority of his works adapted into feature films (albeit with mixed results), with eleven adaptations produced to date, including Joe Wright’s critically-lauded 2007 version of Atonement.

Before you crack open McEwan’s latest, here’s a list of what we believe to be his five most essential novels.

Disagree with our choices? Let us know in the comments!

*

The Cement Garden (1978)

A psychosexual, Lord of the Flies-esque tale of four British children who, fearful of being taken into foster care, hide their mother’s death from the outside world by encasing her corpse in cement in the cellar. McEwan’s pitch-black debut novel, coming on the heels of two equally dark short story collections, earned the young author the nickname “Ian Mcabre.”

“This brief novel is really a kind of extended dream, although there’s nothing dreamy about the precision and clarity of the writing. Its narrator, Jack, is a 15-year-old English boy so sunk in self-loathing that there are long stretches when he can’t even be bothered to bathe or brush his teeth. Jack’s father is a crabbed, oppressive man whose greatest pride is a tightly constructed garden of plaster, plastic, rocks and widely spaced tulips; his mother is not much more than a shadow, and their neighborhood is a wasteland of abandoned prefabs. Life here seems smothered, flattened. For Jack, his two sisters and his little brother, the only pleasures are those that erupt beneath a rigid surface: some rather joyless sexual games and a few stolen moments of willful disobedience. The Cement Garden describes the process that steadily isolates these four children, until they’re so absolutely alone and so at odds with the rest of the world that there is not way of returning to normal life … what makes the book difficult is that these children are not—we trust—real people at all. They are so consistently unpleasant, unlikable and bitter that we can’t believe in them (even hardened criminals, after all, have some good points) and we certainly can’t identify with them. Jack’s eyes, through which we’re viewing this story, have an uncanny ability to settle upon the one distasteful detail in every scene, and to dwell on it, and to allow only that detail to pierce the cotton wool that insulates him … It seems weak-stomached to criticize a novel on these grounds, but if what we read makes us avert our gaze entirely, isn’t the purpose defeated? Jack, we’re being told, has been so damaged and crippled that there’s no hope for him. But if it’s a foregone conclusion that there’s no hope whatsoever, we tend to lose hope in the book as well. Imagine how Beryl Bainbridge might have handled this: the same devastated, English urban scenery, some stunted lives, but a small, manic gleam beneath that saves it all. Ian McEwan is a skillful writer, absolutely in control of his material, but in this first novel, at least, he could use a little more gleam.”

–Anne Tyler, The New York Times, November 26, 1978

“McEwan’s evocative detail and perfect British prose lend a genteel decorum to the death and decay that surround the family. Weeds growing through the rockery of an abandoned garden mark the passage of time. Antique pieces of furniture are placed in childlike arrangements for dining or entertaining, rarely in the rooms designed for such purposes. The smell of trash and rotting food, overflowing from a bin in the untended kitchen, mingles with the sweet, sickly human odors that fill the house. Each detail elevates the story from merely bizarre to hauntingly detestable. In fact, by the end of the novel, the minutiae of the environment—rather than the characters’ actions—seem to be driving the story. McEwan, stirring disgust and rapture, builds to an exhilarating conclusion in which the siblings find themselves beyond the point of redemption but completely enthralled by one another. Like Brontë’s Heathcliff, McEwan’s lovers are loathsome, a far cry from the romanticized versions in the 1993 film adaptation. But they’re all the more captivating for it.”

–Elaina Patton, The New Yorker, September 12, 2018

Enduring Love (1997)

Famed for having the most shocking opening of any McEwan novel, Enduring Love begins with a terrible tragedy on a cloudless sunny day and becomes a dark tale of religious and sexual obsession as two witnesses to the freak accident become entwined in one another’s lives.

“What’s striking about McEwan’s later work—I’m thinking particularly of The Innocent, Black Dogs and his new novel Enduring Love—is its intimacy with evasion and failure, combined with an alert intelligence about these things which itself looks like grounds for hope. McEwan’s characters talk past each other, go manic, stumble into violence, cultivate suspicions, hide behind brilliant illusions. They probably can’t help or save themselves, or not many of them can, but it’s hard to believe that such patient and delicate understanding of their condition won’t help someone … what about the man who held on and died, did he show force of character or just folly? The parable makes painfully clear not only our need for others, but our need for faith in others, for trust in their staying with us. It’s not that the men are not a team or don’t have a leader, it’s that they can’t imagine, because they don’t have time, or because their fear is larger than everything else, the practical appeal of solidarity in this instance: the danger will disappear if everyone hangs on, but only if they do. What Joe can’t acknowledge is the amoral strength of his fear—not, as Clarissa writes to him late in the book, ‘the thought that it might have been you who let go of the rope first,’ but the fact that he let go of the rope at all—and the revealed inadequacy of going it alone, either letting go or hanging on. As the story unfolds, it is evident that dependence and interdependence are the ideas McEwan wants us to think through, although nothing prepares us, or Joe, for what happens next or the turn these ideas take. This is where the parable opens brilliantly into a novel.”

–Michael Wood, London Review of Books, September 4, 1997

“The stunning beginning of McEwan’s latest novel delivers a vivid visceral jolt: six men run across a verdant English field, each bent on rescuing a man dangling by a rope from a helium balloon while a small boy cowers in the basket, about to be swept away. One of the would-be rescuers will become a victim instead, falling to his death. But the tragedy is just the catalyst of what will be another one of McEwan’s eerie stories of bizarre events and personal obsessions. As always, his work is imbued with a mounting sense of menace as the unthinkable intrudes into the everyday … McEwan wrings wry meaning from the contrast of poetry and science, the limitations of rational logic and the delusive emotional temptations of faith. As he investigates the nature of obsessive love, McEwan takes some false steps in explaining Clarissa’s misperceptions of Joe’s behavior, somewhat lessening his story’s credibility but not its powerful impact. Perhaps it is this lapse that persuaded the Booker judges not even to nominate the book, touted by the British press early on as a sure choice for winner. Whatever its limitations, however, the tightly controlled narrative, equally graced with intelligent speculation and dramatic momentum, will keep readers hooked.”

–Publishers Weekly, December 29, 1997

Atonement (2001)

Considered by many to be McEwan’s masterpiece, this metafictional story of love, war, regret (so much regret) and the nature of writing concerns a young upper class English girl in the 1930s whose lie destroys the happiness of two innocent lovers and shadows her throughout her life.

“It is certainly his finest and most complex novel. It represents a new era in McEwan’s work, and this revolution is achieved in two interesting ways. First, McEwan has loosened the golden ropes that have made his fiction feel so impressively imprisoned…and second, McEwan uses his new novel to comment on precisely the kind of fiction that he himself has tended to produce in the past … I doubt that any English writer has conveyed quite as powerfully the bewilderments and the humiliations of this episode in World War II. After more than twenty years of writing with care and control, McEwan’s anxious, disciplined richness of style finally expands to meet its subject … Atonement ends with a devastating twist, a piece of information that changes our sense of everything we have just read….This twist, this revelation, further emphasizes the novel’s already explicit ambivalence about being a novel, and makes the book a proper postmodern artifact, wearing its doubts on its sleeve, on the outside, as the Pompidou does its escalators.”

–James Wood, The New Republic, March 25, 2002

“Ian McEwan’s remarkable new novel Atonement is a love story, a war story and a story about the destructive powers of the imagination. It is also a novel that takes all of the author’s perennial themes—dealing with the hazards of innocence, the hold of time past over time present and the intrusion of evil into ordinary lives—and orchestrates them into a symphonic work that is every bit as affecting as it is gripping. It is, in short, a tour de force … The novel, supposedly a narrative constructed by one of the characters, stands as a sophisticated rumination on the hazards of fantasy and the chasm between reality and art … There is nothing self-conscious or mannered about Mr. McEwan’s writing. Indeed Atonement emerges as the author’s most deeply felt novel yet—a novel that takes the glittering narrative pyrotechnics perfected in his last book, Amsterdam, and employs them in the service of a larger, tragic vision.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times, March 7, 2002

On Chesil Beach (2007)

Brief. Excruciating. Devastating. On Chesil Beach concerns two young, inexperienced newlyweds arriving at an English seaside hotel in 1962 to celebrate their honeymoon, only for buried trauma, performance anxiety, and a disastrous first attempt at sex to destroy their relationship.

“Our appetite for Ian McEwan’s form of mastery is a measure of our pleasure in fiction’s parallax impact on our reading brains: his narratives hurry us feverishly forward, desperate for the revelation of (imaginary) secrets, and yet his sentences stop us cold to savor the air of another human being’s (imaginary) consciousness. McEwan’s books have the air of thrillers even when, as in On Chesil Beach, he seems to have systematically replaced mortal stakes—death and its attendant horrors—with risks of embarrassment, chagrin and regret … The bulk of On Chesil Beach consists of a single sex scene, one played, because of the novel’s brevity and accessibility, in something like ‘real time’…The situation is miniature and enormous, dire and pathetic, tender and irrevocable. McEwan treats it with a boundless sympathy, one that enlists the reader even as it disguises the fact that this seeming novel of manners is as fundamentally a horror novel as any McEwan’s written.”

–Jonathan Lethem, The New York Times Book Review, June 3, 2007

“This short novel takes place on the first night of their honeymoon, with many flashbacks, and at the end a great flash forward, and at the core an enormous misunderstanding … It is difficult to judge whether to give away the plot of this book…is to lessen its impact on the reader. McEwan writes prose judiciously; his books seem to depend on plain writing and story and careful plotting, with much detail added to make the reader believe that these words on the page must be followed and believed as the reader would follow and believe a well-written piece of journalism. On Chesil Beach, however, is full of odd echoes and has elements of folk tale, which make the pleasures of reading it rather greater than the joys of knowing what happened in the end.”

–Colm Toibín, The London Review of Books, April 26, 2007

Nutshell (2016)

McEwan’s polarizing 2016 novel is a gleefully Stoppardian Shakespeare riff about a modern day Hamlet in utero. A fetus, only days from birth and possessing of a prodigious intellect and vocabulary, finds himself eavesdropping on his mother and uncle’s plot to murder his father.

“With Nutshell, Ian McEwan has performed an incongruous magic trick, mashing up the premises of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Amy Heckerling’s 1989 movie, Look Who’s Talking, to create a smart, funny and utterly captivating novel … Nutshell is a small tour de force that showcases all of Mr. McEwan’s narrative gifts of precision, authority and control, plus a new, Tom Stoppard-like delight in the sly gymnastics that words can be perform … It’s preposterous, of course, that a fetus should be thinking such earthshaking thoughts, but Mr. McEwan writes here with such assurance and élan that the reader never for a moment questions his sleight of hand. At the same time, his unborn Hamlet’s soliloquy leaves us with a snapshot of part of London that’s as resonant as the portrait of the post-9/11 world he created in his Mrs. Dalloway-inspired novel Saturday, a snapshot of how a slice of the privileged West lives—and worries—today.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times, September 5, 2016

“Ian McEwan’s preposterously weird little novel, is more brilliant than it has any right to be … If you can get beyond that icky premise, you’ll discover a novel that sounds like a lark but offers a story that’s surprisingly suspenseful, dazzlingly clever and gravely profound. To the extent that Hamlet is an existential tragedy marked with moments of comedy, Nutshell is a philosophical comedy marked by moments of tragedy. … Nutshell offers the unmatched pleasure of McEwan’s prose, inflected with witty echoes of Shakespeare … It doesn’t seem possible that this oddly ridiculous narrator caught in a tawdry murder scheme could deliver such a moving, hilarious testimony, filled with equal measures of dread and hope, but babies and sweet princes can surprise you.”

–Ron Charles, The Washington Post, September 12, 2016