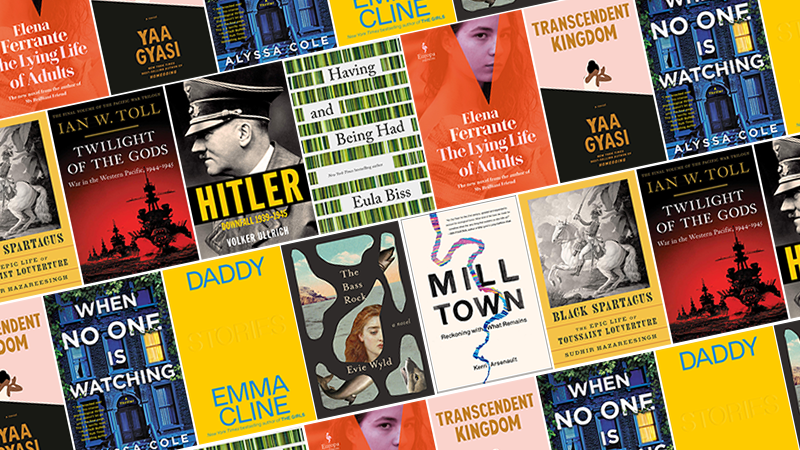

Elena Ferrante’s The Lying Life of Adults, Yaa Gyasi’s Transcendent Kingdom, Emma Cline’s Daddy, Kerri Arsenault’s Mill Town, and Eula Biss’ Having and Being Had all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Week.

1. The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante

13 Rave • 16 Positive • 3 Mixed

“What a relief it is when an author who has written a masterpiece returns to prove the gift intact … translated once again by the nimble and attentive Goldstein … Adolescence remains rich territory for Ferrante. Here as in her past work, she captures the interior states of young people with an unflinching psychological honesty that is striking in its vividness and depth. We share in Giovanna’s embarrassments, the tortured logic of her self-soothing, her temptations and decisions that accrete into something like experience…Ferrante’s genius is to stay with the discomfort. With the same propulsive, episodic style she perfected in the Neapolitan quartet, she traces how it is that the consciousness of a girl at 12 becomes that of a young woman at 16 … The change in period makes all the difference. Setting Giovanna’s coming-of-age in the early 1990s, Ferrante slyly asks how decades of feminism and reaction have changed the world since the Neapolitan novels’ Lila and Lenù were teenagers.”

–Dana Tortorici (The New York Times Book Review)

Read the opening of The Lying Life of Adults here

2. Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

9 Rave • 1 Positive

“Ms. Gyasi has trained her ambitions inward, applying the same rigorous attention to the quality of her sentences and to the laser-like interrogation of her themes. She has produced a powerful, wholly unsentimental novel about family love, loss, belonging and belief that is more focused but just as daring as its predecessor, and to my mind even more successful … The narrative of difficult, immigrant striving is derailed by a slow-motion tragedy … Unlike many novels centered on suffering, Ms. Gyasi’s book is not interested in eliciting sympathy or activating the reader’s guilt. It is, instead, burningly dedicated to the question of meaning … confidently shuttles between the poles of faith and science—it quotes the Bible as fluently as it discusses neural circuits in the medial prefrontal cortex—plumbing each for comforts and insights but also dispassionately studying the ways that each falls short … a hard, beautiful, diamantine luster.”

–Sam Sacks (The Wall Street Journal)

Listen to an interview with Yaa Gyasi here

3. When No One Is Watching by Alyssa Cole

6 Rave • 1 Positive

“By now, many will have seen When No One Is Watching described as Rear Window meets Get Out. Those comparisons are shockingly apt. Alyssa Cole’s latest triumph incorporates elements of both psychological thriller and social horror. Its finale is a bit macabre, much like Get Out, and there is a romantic subplot as well, just as there was in Hitchcock’s masterpiece … highly original … Perhaps the best evidence of Cole’s skill in this regard is the remarkable correspondence between a fictional event in the book and a real-life incident that occurred just miles away from where the book is set … Another element that distinguishes When No One Is Watching is its grounding in not just present-day politics but history.”

–Carole V. Bell (BookPage)

Read Alyssa Cole’s “5 Ways to Think About Social Injustice Through Crime Fiction” here

4. Daddy by Emma Cline

4 Rave • 4 Positive

“… if Emma Cline’s readers were holding out hope that she’d top her explosive breakout The Girls with a more seductive charge, well, a suggestive title like Daddy could hardly dash it. Yet this pitch-black collection of 10 stories emerges as its own kind of success by quietly rushing in another direction … None of the plots will elicit much intrigue on topic alone … It’s the stuff of niche literary darlings, not blockbuster best-sellers. The pieces soar independently—dark slices of life confidently weaving between styles—and in unison, portraits of young women seeking liberation, of older men doing wrong. True, the standout—’Marion,’ a dizzyingly complex tale unfurling from an 11-year-old girl’s mind—feels closer to what made Cline a household name, but Daddy’s biggest reward lies in her showing us something new.”

–David Canfield (Entertainment Weekly)

Read some rapid-fire book recs from Emma Cline here

5. The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld

3 Rave • 5 Positive • 1 Mixed

“… a complex, searingly controlled catalogue of male violence against women … The elegant patterning of the novel’s structure and the delicate links between the three narrative threads stand in contrast to the brutal material … It is, inevitably, a furious and painful reading experience: by page 10 alone, we’ve encountered a woman’s dismembered body in a suitcase, a disquisition on misogynistic advertising and a threatening stranger in a car park. But the novel is also psychologically fearless and, in Viviane’s sections, bitterly funny. Wyld is a genius of contrasting voices and revealed connections, while her foreshadowings are so subtle that the book demands – and eminently repays – a second read … There are many more characters and connections in this dense, complicated book, which is a gothic novel, a family saga and a ghost story rolled into one, as well as a sustained shout of anger.”

–Justine Jordan (The Guardian)

**

=1. Mill Town: Reckoning With What Remains by Kerri Arsenault

4 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

“In this powerful investigative memoir, book critic Arsenault examines her relationship with Mexico, Maine, her now-downtrodden hometown … Arsenault paints a soul-crushing portrait of a place that’s suffered ‘the smell of death and suffering’ almost since its creation. This moving and insightful memoir reminds readers that returning home—’the heart of human identity’—is capable of causing great joy and profound disappointment.”

Read an excerpt from Mill Town here

=1. Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture by Sudhir Hazareesingh

4 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

“… a tour de force: by far the most complete, authoritative and persuasive biography of Toussaint that we are likely to have for a long time. It is not without its own very strong point of view, presenting Toussaint above all as a fierce and effective opponent of slavery. But it is at times an extraordinarily gripping read … The book is grounded in a remarkable job of research. Hazareesingh has scoured archives in France, Britain, the US and Spain (not Haiti itself, where, regrettably, relatively little material has survived). He has not been able to resolve some of the greatest open questions about Toussaint, such as whether the black leader plotted the slave rebellion at the behest of French royalists, who hoped it would undercut moves towards independence by white landowners. Rumours to this effect have circulated since the events themselves. Hazareesingh does not believe them, but has little new evidence. However thanks above all to new soundings in the French colonial archives, including both the correspondence of French officials and records of the colonial administration, he has provided a far richer portrait of Toussaint’s years in power than was previously available.”

–David A. Bell (The Guardian)

3. Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945 by Ian W. Toll

5 Rave • 1 Positive

“Toll skillfully shifts his narrative focus throughout all of this from the broad-scale operational side of things to the personal and even anecdotal … Naturally, the book’s tragic, dramatic high point deals with the main reason for that abrupt surrender: the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Toll narrates this gruesomely familiar part of his story with the solemnity of a modern-day morality play; every detail is familiar from earlier accounts, but he imbues them a very readable austerity, as when he’s dealing with the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima … the title’s meaning is a bit of a mystery to me … traffics in such familiar narratives throughout its length, always guided by Toll’s spare eloquence and obvious mastery of his vast array of source materials. The Pacific Theater has had entire libraries of histories written about it over the last seven decades (with many, many more such histories to come, since 2021 marks a nice clean 80 year anniversary of its beginning), and Toll has written a trilogy fit to stand with some of the best of them.”

–Steve Donoghue (Open Letters Review)

4. Hitler: Downfall: 1939-1945 by Volker Ullrich

5 Rave • 1 Mixed

“… meticulous … For some readers, Ullrich’s portrait of Hitler may be difficult to take, since we are so used to seeing him as inhuman, even subhuman, a madman or a beast. Even Sir Ian Kershaw, whose two-volume biography represents the gold standard in 20th-century history, saw Hitler as a ‘non-person’, a lazy, talentless mediocrity onto whom people projected their hopes and anxieties … But Ullrich argues that Hitler was all too human. And although his second volume covers almost exactly the same period as Kershaw’s second book —the Second World War—the focus is quite different. Kershaw’s real interest lay in the Nazi dictatorship. Ullrich is more interested in Hitler the man … [Ullrich] is also excellent on the dictator’s health and appearance … Some of this, of course, is very familiar: the rages, the Stauffenberg bomb plot, the final scenes in the bunker. So if you know the story, do you need to bother? … The answer is yes. Smoothly written and splendidly translated, Ullrich’s book gives us a Hitler we have not seen before, at once cold-blooded and idealistic, chillingly narcissistic and cloyingly sentimental. And precisely because he seems so much like the rest of us, it is probably the most disturbing portrait of Hitler I have ever read.”

–Dominic Sandbrook (The Times)

5. Having and Being Had by Eula Biss

2 Rave • 3 Positive • 2 Mixed

“Bliss enlivens her own critique of capital in the 2020s by delving into the trouble we all avoid discussing—and then staying with it … A middle-age, middle-class white American writer and professor, Biss lays bare her own privilege from the start … Loose in its greater arc but always tethered to an awareness of the insidious influence of capitalism, each essay originates in conversation or personal observation. This allows her to explore the candid ways we reveal our own biases around money, class, wealth, property and work … I’d argue that Having and Being Had is a reminder that even discussing our contemporary chaos is an act of awakening and a call to action … Ultimately, this is not a book that aims for catharsis or redemption … Biss examines these stories of ideas in order to help us live with our fate—asking, among other questions: To what degree can we come to know our passions as something free from consumerism? How can we live a life of dignity—with flashes even of luxury and indulgence—without sacrificing ourselves through work without joy or income beyond purpose?”

–Lauren Le Blanc (The Los Angeles Times)

Read Eula Biss on the anticapitalist origins of Monopoly here