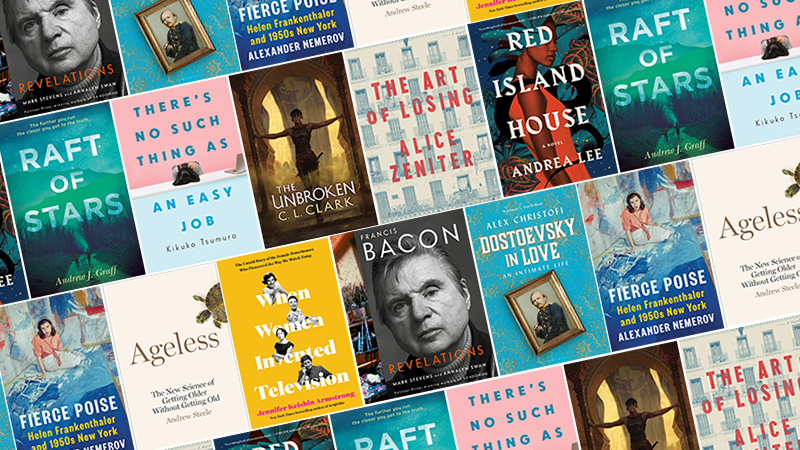

Andrea Lee’s Red Island House, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s Francis Bacon, Andrew J. Graff’s Raft of Stars, and Alexander Nemerov’s Fierce Poise all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Week.

1. Red Island House by Andrea Lee

(Scribner)

5 Rave • 4 Positive

“Lee’s superb fiction often describes the collisions between people who hail from different cultures. She returns to this fertile ground in a new novel but widens her scope, suggesting some historical wounds are too deep to heal, and even a woman who believes she has stepped beyond her own tribal identity can never free herself totally … Lee isn’t writing magical realism per se—she is conjuring up a locale where the power of superstition still holds sway … because the story is told in stand-alone stories, Red Island House has less propulsive power than Lee’s stirring 2006 novel, Lost Hearts in Italy … But these are niggling criticisms of a gorgeous narrative that perhaps only Lee could have constructed—an ambitious attempt to use fiction to explore the reality of a world fractured by race and class, and divided between the haves and the have-hardly-anything-at-alls.”

–Clare McHugh (The Washington Post)

2. Raft of Stars by Andrew J. Graff

(Ecco)

4 Rave • 5 Positive

Read an essay by Andrew J. Graff here

“… [an] accomplished debut … Nature is not mere backdrop here, but a rushing, thrummingly alive presence … This novel is…romantic, but also compellingly real. And the art and craft of this narrative, apparent from the first page with its sublime constellations of images, offers brutal beauty, the glinting edge of truth, and the possibility of redemption for the fifth-grade boys, and also for the adults chasing them … both children and adults show they can transcend the thicket of confusion surrounding their personal circumstances and emerge toward more clarity, proving they all are more than just ‘poor damn things.'”

–Jeffrey Ann Goudie (The Boston Globe)

3. There’s No Such Thing as an Easy Job by Kikuko Tsumura

(Bloomsbury)

2 Rave • 8 Positive

“Taking her place among a growing number of exceptional female writers in Japan, Tsumura deftly handles work habits and relationships, stereotypes and expectations for success, all of which are set against a repetitious, unending search for what is valuable and valued. The novel unfolds as a profound meditation on contemporary society and what makes work meaningful … part of the novel’s appeal lies in the narrator’s distinct worldview and her deadpan humor that allows the surreal, metaphysical connections in the novel to bubble beneath the surface of her seemingly dull, day-to-day existence … It’s the kind of novel that presents a swathe of tangled threads, trusting the reader to weave together the connections on their own. After the last page, I immediately started again, excited to unravel the nuances of each section.”

–Kris Kosaka (The Japan Times)

4. The Unbroken by C. L. Clark

(Orbit)

5 Rave

“Clark conjures an elaborate fantasy world inspired by Northern Africa and delves into an international political conflict that draws on real histories of colonialism and conquest in their excellent debut, the first in the Magic of the Lost series … Clark’s precise, thorough worldbuilding allows this remarkable novel to dive deep into the intricate workings of colonialism, exposing how power structures are maintained through social conditioning and exploring the emotional toll of political conflict. The result is a captivating story that works both as high fantasy and skillful cultural commentary.”

5. The Art of Losing by Alice Zeniter

(FSG)

3 Rave • 2 Positive

“Zeniter has used fiction to demystify the war, its evolution and its fallout through an enthralling saga of three generations of a family from Algeria’s mountainous Kabylia region who left the country in 1962 and moved to France … Ms. Zeniter’s extraordinary achievement is to transform a complicated conflict into a compelling family chronicle, rich in visual detail and lustrous in language. Her storytelling, splendidly translated by Frank Wynne, carries the reader through different generations, cities, cultures, and mindsets without breaking its spell … Ms. Zeniter shows fiction’s power as a hedge against loss of the past: the art of regaining.”

–Liesl Schillinger (The Wall Street Journal)

**

1. Francis Bacon: Revelations by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan

(Knopf)

5 Rave • 5 Positive • 3 Mixed

“[A] definitive life … Stevens and Swan furnish an exhaustive account, painting by painting, exhibition by exhibition, of how Bacon’s wild innovations in figurative art countered the mid-20th-century fashions for both abstract expressionism and pop art. They have great fun, too, as they chronicle Bacon’s wit, charm, extravagance, and cruelty … Stevens and Swan are vivid scene setters. They’re also shrewd evaluators of the people in Bacon’s life, including painter Lucian Freud and Bacon’s doomed lovers Peter Lacy and George Dyer … does justice to the contradictions of both the man and the art.”

–Michael Upchurch (The Boston Globe)

2. Dostoevsky in Love: An Intimate Life by Alex Christofi

(Bloomsbury Continuum)

4 Rave • 5 Positive • 1 Mixed

“So as not to interrupt the narrative flow, the sources are given only at the back of the book. It’s a witty motif which works well, not least because it immerses us in the forcefield of Dostoevsky’s thought, which Christofi also employs to explain his own waywardness … Novelists tend to make good biographers, not least because they know how to shape a story, and it is no mean feat to boil Dostoevsky’s epic life down to 256 pulse-thumping pages. Dostoevsky in Love is beautifully crafted and realized, but it is the great love that Christofi feels for his subject that makes this such a moving book.”

–Frances Wilson (The Guardian)

3. Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York by Alexander Nemerov

(Penguin)

3 Rave • 5 Positive • 2 Mixed • 1 Pan

Read an excerpt from Fierce Poise here

“[A] vibrant, sympathetic portrait … It’s good he finally undertook the project because Frankenthaler, one of the five women artists profiled in Mary Gabriel’s highly regarded 2018 Ninth Street Women is a fascinating subject … Nemerov is a thoughtful and judicious writer. He does a good job of sorting through various criticisms leveled at Frankenthaler over the years … But brevity can be a virtue. In just over 200 pages, Nemerov takes us on a fast, exhilarating ride through the formative decade of her career, providing a lucid introduction to an artist we’re likely to hear more about in the near future.”

–Ann Levin (Associated Press)

4. Ageless: The New Science of Getting Older Without Getting Old by Andrew Steele

(Doubleday)

2 Rave • 5 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Because Steele’s objective is not to entertain you, so much as to mobilise you. His big thought—and it is a very big thought—is that what we call ageing and see as inevitable is in fact just disease and can be prevented … Steele sees our attitudes towards ageing as fatalistic and fundamentally mistaken. We think the tottering old—like the poor—are always with us. That’s the natural way of things. We must eventually become sans eyes, sans teeth, sans undisturbed nights, sans everything. During the pandemic there has been an active anti-lockdown movement which pretty much openly suggests that old people dying a little early is no great disaster. Steele could not disagree more … So don’t expect a philosophical debate about the nature of humanity or a demographic chapter on the population effects. And don’t expect an easy read. For a manifesto it’s tough going for the layperson. It’s not really the casual reader he wants to convince.”

–David Aaronovitch (The Times)

5. When Women Invented Television: The Untold Story of the Female Powerhouses Who Pioneered the Way We Watch Today by Jennifer Keishin Armstrong

(Harper)

2 Rave • 5 Positive

Read an excerpt from When Women Invented Television here

“Armstrong uses her impressive analytic and research skills to unearth some much less-explored ground … The shifts between the four different biographies can be jarring, though helpful at times. Armstrong never comes right out and analyzes the differences in the rises and falls of these women, but it’s quite clear that White had an easier path to success than Scott or Berg did. Those disparities become even more plain in the book’s most gripping section, as both Berg and Scott become ensnared in the Hollywood blacklist during the era of McCarthyism … One might assume that a book about female pioneers in television would have Lucille Ball front and center. She does appear, but her more familiar tale takes a back seat here to these lesser-known stories, which are bolstered by Armstrong’s interviews with Scott’s son and Berg’s grandchildren, and White’s memoirs and other archives. Armstrong also makes strong statements about the fact that women were marking these accomplishments during a time when they were expected to stay home and care for their families … Armstrong’s volume is a definite step in the right direction toward giving just some of these forgotten women their due.”

–Gwen Ihnat (The AV Club)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.