2020—the longest year that has ever been—is almost at an end, and that means it’s time for us to break out the calculators and tabulate the best reviewed books of past twelve months.

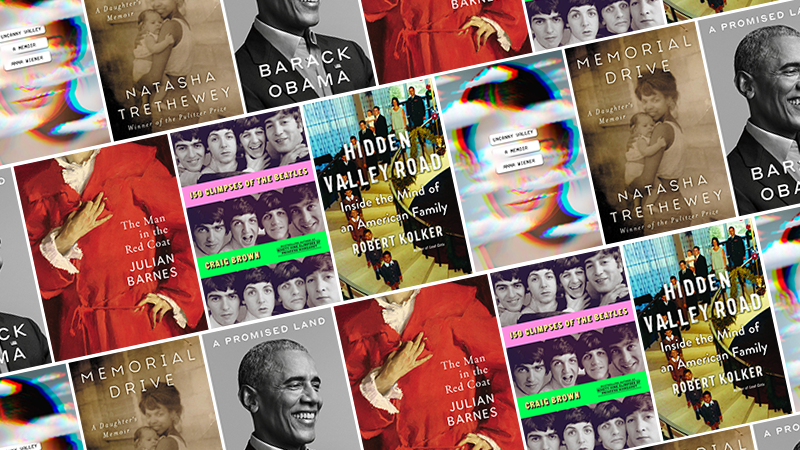

Yes, using reviews drawn from more than 150 publications, over the next two weeks we’ll be revealing the most critically-acclaimed books of 2020, in the categories of (deep breath): Memoir & Biography, Sci-Fi & Fantasy, Short Story Collections, Essay Collections, Graphic Literature, Poetry, Mystery & Crime, Literature in Translation, General Fiction, and General Nonfiction.

First up: Memoir and Biography.

1. Uncanny Valley by Anna Wiener

(MCD)

10 Rave • 19 Positive • 6 Mixed

Read a Profile of Anna Wiener here

“Wiener was, and maybe still is, one of us; far from seeking to disabuse civic-minded techno-skeptics of our views, she is here to fill out our worst-case scenarios with shrewd insight and literary detail … Wiener is a droll yet gentle guide … Wiener frequently emphasizes that, at the time, she didn’t realize all these buoyant 25-year-olds in performance outerwear were leading mankind down a treacherous path. She also sort of does know all along. Luckily, the tech industry controls the means of production for excuses to justify a fascination with its shiny surfaces and twisted logic … It’s possible to create a realistic portrait of contemporary San Francisco by simply listing all the harebrained new-money antics and ‘mindful’ hippie-redux principles that flourish there. All you have to do after that is juxtapose them with the effects of the city’s rocket-ship rents: a once-lively counterculture gasping for air and a ‘concentration of public pain’ shameful and shocking even to a native New Yorker. Wiener deploys this strategy liberally, with adroit specificity and arch timing. But the real strength of Uncanny Valley comes from her careful parsing of the complex motivations and implications that fortify this new surreality at every level, from the individual body to the body politic.”

–Lauren Oyler (The New York Times Book Review)

2. Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey

(Ecco)

20 Rave • 3 Positive

Listen to an interview with Natasha Trethewey here

“Memorial Drive is, among so many other wondrous things, an exploration of a Black mother and daughter trying to get free in a land that conflates survival with freedom and womanhood with girlhood … A book that makes a reader feel as much as Memorial Drive does cannot be written without an absolute mastery of varied modes of discourse … In one of the book’s most devastating and artful chapters, Trethewey makes an unexpected but wholly necessary switch to the second person … What happens in most riveting literature is seldom located solely in plot. I’ve not read an American memoir where more happens in the assemblage of language than Memorial Drive … Memorial Drive forces the reader to think about how the sublime Southern conjurers of words, spaces, sounds and patterns protect themselves from trauma when trauma may be, in part, what nudged them down the dusty road to poetic mastery.”

–Kiese Makeba Laymon (The New York Times Book Review)

3. A Promised Land by Barack Obama

(Crown)

11 Rave • 14 Positive • 5 Mixed

“The Obama of A Promised Land seems complicated or elusive or detached only if you think that these two elements of the president’s job—the practical and the symbolic—must be made to add up in every particular. Obama himself doesn’t. Even at his most inspiring, he was never a firebrand speechifier. He preached faith in the ability of Americans’ commonalities to overcome their differences. This is a creed in which he continues to believe, even if A Promised Land contains its share of dark allusions to the advent of division and acrimony in the form of Donald Trump. Obama is not angry, the sole quality that seems obligatory across party lines in every form of political discourse today … while A Promised Land is a pleasure to read for the intelligence, equanimity, and warmth of its author—from his unfeigned delight in his fabulously wholesome family to his manifest fondness for the people who worked for and with him, especially early on—it’s also a mournful one. Not because Obama doesn’t believe in us anymore, but because no matter how much we adore him, we no longer believe in leaders like him.”

–Laura Miller (Slate)

4. Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald

(Grove)

18 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

Read Helen MacDonald’s “The Things I Tell Myself When I’m Writing About Nature” here

“… a stunning book that urges us to reconsider our relationship with the natural world, and fight to preserve it … The experience of reading Vesper Flights is almost dizzying, in the best possible way. Macdonald has many fascinations, and her enthusiasm for her subjects is infectious. She takes her essays to unexpected places, but it never feels forced … Macdonald is endlessly thoughtful, but she’s also a brilliant writer—Vesper Flights is full of sentences that reward re-reading because of how exquisitely crafted they are … What sets Vesper Flights apart from other nature writing is the sense of adoration Macdonald brings to her subjects. She writes with an almost breathless enthusiasm that can’t be faked; she’s a deeply sincere author in an age when ironic detachment seems de rigueur … a beautiful and generous book, one that offers hope to a world in desperate need of it.”

–Michael Schaub (NPR)

5. What is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life by Mark Doty

(W. W. Norton & Company)

11 Rave • 8 Positive • 1 Mixed

Read an excerpt from What is the Grass here

“… excellent … as a major poet who worked at both evading and establishing his sexual identity, [Whitman] is almost a perfect topic for Doty, who recalls (in some of this book’s most powerful opening chapters) his own youth spent trying to live his life as others expected him to live it … Doty has long been one of our best living American poets, and his recent memoirs, including 2008’s Dog Years, prove him one of our best prose writers as well. What is the Grass doesn’t possess a single inelegant sentence or poorly expressed thought. Doty does what traditional academic criticism often fails to do: He makes poetry part of how we live and how we think about living … [Doty] doesn’t simply ‘analyze’ poems or narrate events; instead he continually illuminates how those who love books can grow old reading writers who help make sense of their lives … provides an excellent opportunity to re-examine the work of one of America’s first major poets through the prose of one of its best living ones.”

–Scott Bradfield (The Washington Post)

1. The Man in the Red Coat by Julian Barnes

(Knopf)

8 Rave • 20 Positive

Read an excerpt from The Man in the Red Coat here

“Barnes is fascinated by facts that turn out to be untrue and by unlikely but provable connections between people and things … While Barnes is concerned in this book to find things that don’t add up, he also relishes the moments when a clear, connecting line can be drawn … Wilde and Pozzi, and perhaps even Montesquiou, admired Bernhardt; Pozzi and James were both painted by Sargent; Wilde and Montesquiou had the same response to the interior décor at the Prousts. Barnes enjoys these connections. But in ways that are subtle and sharp, he seeks to puncture easy associations, doubtful assertions, lazy assumptions. He is interested in the space between what can be presumed and what can be checked.”

–Colm Tóibín (The New York Review of Books)

2. 150 Glimpses of the Beatles by Craig Brown

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

12 Rave • 5 Positive • 2 Mixed

“… riveting … This quirky, irreverent book, written in the manner of Mr. Brown’s bestselling Ninety-Nine Glimpses of Princess Margaret (2017), is a kaleidoscope of essays, anecdotes, party lists and personal reminiscence. You might think there was nothing more to be said about the Beatles, but Mr. Brown, a perceptive writer and a gifted satirist, makes familiar stories fresh. Along the way he unearths many fascinating tidbits … a fascinating study of the cultural and social upheaval created by the band … Mr. Brown has a keen eye for absurdist detail … After reading this book I was inspired to listen to them again. I felt just as I had the first time: sheer joy.”

–Moira Hodgson (The Wall Street Journal)

3. Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family by Robert Kolker

(Doubleday)

14 Rave • 1 Positive

Listen to an interview with Robert Kolker here

“… part multi-generational family saga, part medical mystery, written with an extraordinary blend of rigor and empathy. The reporter in Kolker seeks accuracy above all, but there’s a notable lack of judgment in the book that feels remarkable in light of the stigma long felt by those who have the condition in their families … despite the lonely battles fought by both patients and researchers, Kolker’s Hidden Valley Road is at heart a book about how progress, personal or scientific, can never be achieved on our own.”

–Kate Tuttle (The Los Angeles Times)

4. Stranger in the Shogun’s City: A Japanese Woman and Her World by Amy Stanley

(Scribner)

13 Rave • 1 Positive

“Through Tsuneno, a woman with no remarkable talents or aspirations, Stanley conjures a teeming world … Tsuneno’s restlessness and bad luck make her a rewarding subject … Stanley’s primary materials are letters from Tsuneno and her relatives, which are delightfully frank … The couple squabble, divorce, and remarry, and Tsuneno’s fortunes continue their erratic, fascinating fall and rise and fall … a lost place appears to the reader as if alive and intact.”

–Lidija Haas (Harper’s)

5. Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark

(Knopf)

11 Rave • 3 Positive • 3 Mixed

Read an excerpt from Red Comet here

“…just as one is wondering whether there can possibly be anything new to be said, here comes Heather Clark’s Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath hurtling down the chute, weighing in at more than 1,000 densely printed pages … as Plath and her complex, much analyzed legacy fade with the passing of successive generations, and her work grows more removed from the cultural mainstream, now seems a prime moment to revive her tale and try to bring all of its elements together … poignant … Clark is at pains to see Plath clearly, to rescue her from the reductive clichés and distorted readings of her work largely because of the tragedy of her ending … there is no denying the book’s intellectual power and, just as important, its sheer readability. Clark is a felicitous writer and a discerning critic of Plath’s poetry … Instead of depleting my interest in Plath, the book stimulated it further … Clark’s talent for scene-painting and inserting the stray but illustrative detail contributes to create a harrowing picture of the narrow confines of the London that Plath had moved to with such high hopes.”

–Daphne Merkin (The New York Times Book Review)

*

Our System: RAVE = 5 points • POSITIVE = 3 points • MIXED = 1 point • PAN = -5 points