Yesterday was the one-hundredth birthday of Lawrence Ferlinghetti: WWII veteran; co-founder of City Lights, one of the nation’s great independent bookstores; publisher of iconic beat poetry, including Allen Ginsburg’s Howl, for which he was arrested; self-described philosophical anarchist; and inaugural poet laureate of San Francisco. As Robert Pinsky wrote recently the New York Times, “Ferlinghetti has not just survived for a century: He epitomizes the American culture of that century.”

The indomitable San Franciscan trailblazer has been writing, publishing, running vibrant literary salons, and rattling cages for over sixty-five years, and just last week, as a “literary last will and testament,” he released Little Boy—a wild, sweeping work of semi-autobiographical fiction, “part autobiography, part summing up, part Beat-inflected torrent of language and feeling, and all magical.”

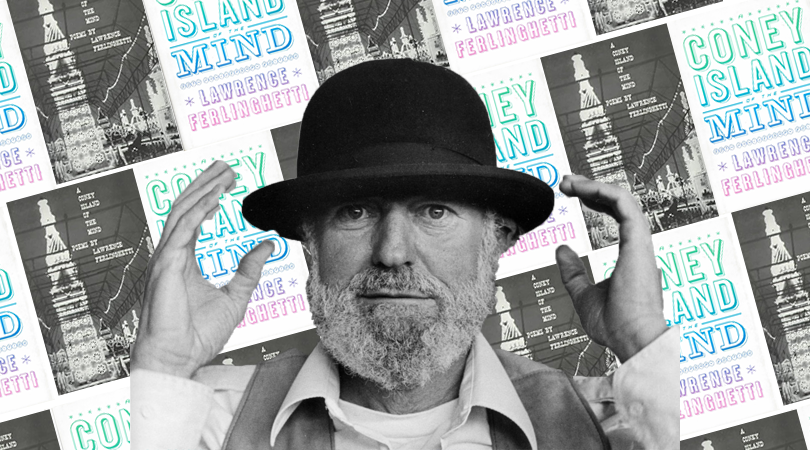

To mark this most monumental of birthdays, we thought we’d go right back to where it all began and revisit the reviews of Ferlinghetti’s seminal, million-selling 1958 debut collection, A Coney Island of the Mind.

*

I once started out

to walk around the world

but ended up in Brooklyn

“Owner of the City Light bookshop (headquarters of the San Francisco literary movement) and publisher of the Pocket Poets Series (most notable entry, Allen Ginsberg’s Howl), Lawrence Ferlinghetti has been a leader in all that jazz about poetry on the West Coast. He now appears with some verse of his own which I find highly readable and ofter very funny.

…

“His program (as quoted on the back of his book) is ‘to get poetry out of the inner esthetic sanctum and out of the classroom into the street’ He puts it most honestly in his verse: ‘I am a social climber/climbing downward/And the descent is difficult.’ For like many writers who keep pointing to their bare feet, Ferlinghetti is a very bookish boy: his hipster verse frequently hangs on a literary reference. His book is a grab bag of undergraduate musings about love and art, much hackneyed satire of American life, and some real and wry perceptions of it: ‘I am in line/for a top job./I may be moving on/to Detroit./I am only temporarily/a tie salesman.'”

–Harvey Shapiro, The New York Times, September 7, 1958

*

“Like the best books of its generation, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind has lost none of its luster over time. It is also bracingly superior to a lot of poetry it has influenced … Ferlinghetti was San Francisco’s first poet laureate. He is a founder of a thriving landmark, one of America’s most influential independent bookstores, and the founder of a revered publishing house, both named City Lights. He has received national and international honors and is a subversively exuberant patriot, making some people angry and nervous with words and actions that support a consistent ethic of pacifism and free speech.

…

“It is not news that A Coney Island of the Mind is the work of a gifted man who has faced the abyss and refused to be overcome by what must not be denied. Art, truth and citizenship – of country, of world, of the individual and collective spirit – are in need of each other with an ongoing urgency. And make no mistake. The classic poem ‘Christ Climbed Down’ can still be used as legitimate prayer, and as a reminder of how, at their best, his followers have always been unsettling.

‘I contain multitudes,’ Whitman famously declared. Ferlinghetti’s expansive reach in his own early work has rightly been considered equally liberating. For 50 years, he has bestowed permission to ‘goose statues’ and to do whatever else it takes to move life and letters toward a more humane, celebratory place.

Ferlinghetti is a tonic for a world thirsting for the loving outrage and energetic reverence that helped reignite and sustain the enterprise of bard-fueled citizenship. A Coney Island of the Mind was, is, and always will be, a necessary joy.”

–Barbara Berman, The San Francisco Chronicle, April 7, 2008

*

“As a social phenomenon Coney Island of the Mind is truly remarkable. With roughly a million copies in print, few poetry collections come anywhere close to matching its readership. Raw sales, though, only tell part of the story. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, Ferlinghetti’s classic helped lay the artistic foundation for the counterculture movements of the 50s, 60s and beyond, to the point where even today it’s a standard entry point for many wishing to explore the serious literary underground.

But it’s far more that just a cultural signpost. The reason Coney Island of the Mind has held up so well is that it also marks the first full flowering of Ferlinghetti’s considerable poetic gifts. Employing open elastic lines that often seesaw across the page, Ferlinghetti’s verse is a unique combination of Whitmanesque proclamation and Dionysian celebration, where a deep love for life and art is interlaced with call for the human race to finally begin living up to its potential.

…

Fifty years on, Coney Island of the Mind, Ferlinghetti’s artistic and commercial breakthrough, still stands as an excellent example of both his social and poetic contributions, and is not only a worthy but probably a necessary volume for the library of anyone truly serious about understanding where English-language poetry has been and where it is going.”

–Rob Woodard, The Guardian, August 19, 2008

*

“I first found Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind while an undergraduate, finding the wry attacks on the established order refreshing and invigorating. Ferlinghetti protests and rages against the madness of the nuclear age, against the misuse of religion and politics to enslave humanity, and against the colossal indifference that allows all this to happen. He pronounces: ‘Christ climbed down/from His bare Tree/this year/and ran away to where/there were no rootless Christmas trees/hung with candycanes and breakable stars.’ Ferlinghetti aches for a return to the sources, while at the same time deconstructing those sources in a humorous and graceful fashion.

In the ensuing years, I have found Ferlinghetti again and again, each time listening more closely to his mischievous bebop. As an English teacher I found dozens upon dozens of historical and literary allusions, both obvious and hidden. Ferlinghetti takes us down ‘Dante’s final/fire escape,’ spoofing and lionizing, playing with our expectations, taking on Yeats, Eliot, Joyce, Hemingway, Keats, the Bible… ‘I have seen…the Beautiful Dame Without Mercy picking her nose in Chumley’s.’ References like these are interpretations, re-imaginings, and damnations of our received myths. The title itself comes from Henry Miller’s essay ‘Into the Night Life,’ and is, as Ferlinghetti understates in his introductory note, ‘taken out of context.’

But once again Ferlinghetti goes beyond the deconstruction of literary antecedents. At first lines like ‘Let us arise and go now/to the Isle of Manisfree’ seem like parody or ridicule. But as layers upon layers of literature are laid down, the names and phrases disappear into the music of the poetry. A strange harmony takes shape between the jesting of jazz and the classical forms it plays upon. ‘Manisfree’ is more than a parody of Yeats’ actual place name ‘Innisfree;’ it demonstrates a new sensibility within the form of earlier work.

This rich collection seems just as fresh as it did at its publication in 1958, and that should be no surprise. In ‘Autobiography’ Ferlinghetti writes: ‘For I am a still of poetry. I am a bank of song.’ By arranging new, syncopated rhythms and sounds around the language of the past, A Coney Island of the Mind takes us to a place both familiar and startling, liquefying and electrifying the language of life.”

–Eric D. Lehman, Empty Mirror, January 27, 2012

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.