There, up in the sky, she noticed for the first time a gigantic mounded cloud, as large and elaborately moulded as a baroque opera house and lit from below and at the sides by pink and creamy hues. It sailed beyond her, improbable and romantic, following in the blue sky the course she was taking down below. It seemed to her that it must be a good omen.

Article continues after advertisement–Rachel Ingalls, Mrs. Caliban

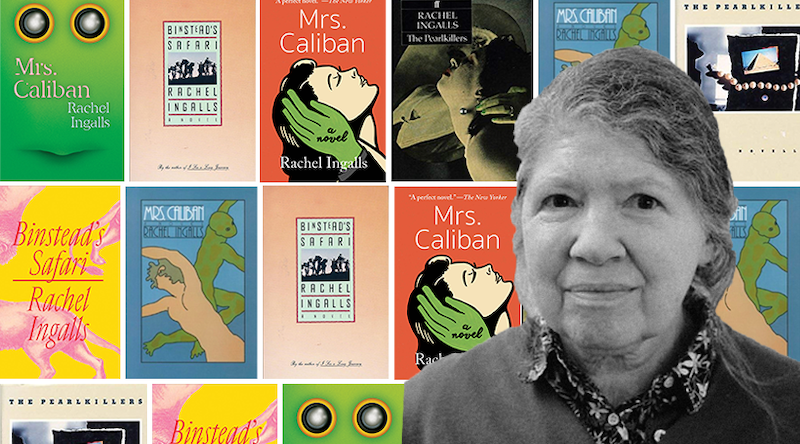

Rachel Ingalls—the American-born, British-based author of Mrs. Caliban (1982), Binstead’s Safari (1983), and several other beautifully strange, sinister, feminist, and unjustly obscure books—passed away on Wednesday at the age of seventy-eight.

The daughter of a housewife and a Harvard Sanskrit professor, Ingalls was raised in Massachusetts and received a B.A. from Radcliffe College before a summer trip to London for the William Shakespeare 400th birthday celebrations— “to see and hear his plays as close to the sources as possible”—convinced her to emigrate permanently to the Bard’s homeland.

Despite winning the Authors’ Club First Novel Award in 1970 for Theft, Ingalls was virtually unknown in the U.S. until 1986, when the British Book Marketing Council named Mrs. Caliban a wild-card entry on a list of the twenty best postwar American novels. This listing (alongside heavyweights like John Updike, Eudora Welty, and Thomas Pynchon) briefly thrust Ingalls, and her slim-but-devastating tale of a grieving suburban housewife who enters into a passionate affair with an fugitive humanoid sea creature, into the literary spotlight—a position in which she was never really comfortable. “I’m not exactly a hermit,” she said once, “but I’m really no good at meeting lots of strangers and I’d resent being set up as the new arrival in the zoo. It’s just that that whole clubby thing sort of gives me the creeps.”

This disinclination towards self-promotion, coupled with the odd, “unsalable” length of her fictions (she favored novellas and short stories) partially explains why, despite glowing reviews, a fevered cult following, and regular interest from Hollywood producers, Ingalls was often referred to as “the best writer you’ve never heard of.”

Indeed, it wasn’t until New York-based independent publishing house New Directions reissued Mrs. Caliban in 2017 that Ingalls began, finally, to receive the widespread acclaim and readership she so richly deserved. The past eighteen months alone have seen a cascade of breathless raves, profiles in the New Yorker and Entertainment Weekly, and even events celebrating the author in absentia. This recognition was long-overdue, but one hopes that Ingalls, who had been ill for some time, was able to enjoy it.

There truly is nothing quite like the fiction of Rachel Ingalls. It casts a spell that leaves you dazed and disquieted. You set down Mrs. Caliban wondering how such terror and tragedy and humor, such poignant oddness and gleeful surrealism, can coexist within so brief a narrative. It feels, to quote a New Yorker review from all those years ago, like “something of a miracle.”

*

Mrs. Caliban (1982)

“…[a] concise, affecting and highly original work … Mrs. Caliban never makes its points head-on, never strays from its intriguing confusions, never beats us over the head with meaning, but somehow we are moved. The book is a strange conversation overheard on a bus: sketchy, incomplete, maddening, but totally unforgettable … Rachel Ingalls has created a tight, intriguing portrait of a woman’s escape from unacceptable reality and presented an account of derangement so matter-of-fact, so ordinary and at the same time so bizarre, that through her words we experience new insight.”

–Michael Dorris (The New York Times)

“Every one of its 128 pages is perfect, original, and arresting. Clear a Saturday, please, and read it in a single sitting … Ingalls’s narrative is a miracle of economy and grace. (Most of her books are novellas, which might explain her obscurity.) She writes straightforwardly, without winking, dropping only occasional hints that Dorothy’s tether on reality might be frayed … Larry’s connection to Caliban is clear enough—he is a frightening other to be feared, enslaved, and, when that fails, exterminated. As a romance, the book is tender; as a portrait of depression, exquisite and tragic. Dorothy can’t swim against the tides of grief and melancholia. Does Larry really exist? ‘This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine’ is not a statement that Mrs. Caliban ever utters.”

–Christine Smallwood (Harper’s)

“…[a] slim surrealist masterpiece … There are many familiar things on which it draws (B-grade monster movies, suburban malaise, romance tropes), and it has been justly compared to cultural touchstones from David Lynch and Richard Yates to The Wizard of Oz and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, but there is nothing else out there that is ‘like’ it, or even close.”

–Justin Taylor (The Los Angeles Times)

*

Binstead’s Safari (1983)

“Though Stan and Millie Binstead aren’t the first couple to be transformed by exposure to the green hills of Africa and surely won’t be the last, Ingalls’ spare and elegant novel owes practically nothing to its predecessors … The tone of the novel deepens into a psychological study of these two people and the subtle and complex ways in which the exotic environment works upon each of them. Though the focus is kept firmly upon Millie and Stan, other central figures reflect different aspects of the African experience. In the course of the narrative, we meet a cross-section of colonials and local inhabitants, each of whom contributes to the composite national portrait without ever losing his or her essential individuality. Even as the mood darkens, Ingalls’ style maintains the wry grace of a sophisticated romance, a control guaranteeing that the denouement will not only be inevitable but astonishing.”

–Elaine Kendall (The Los Angeles Times)

“In clear, elegant prose, Ingalls vividly evokes both the city life of London and the wilderness of Africa, each beautiful in its way, as she explores myth and the human-animal link. With its memorable characters, who face life in their own ways, this is haunting fiction that will linger in memory.”

–Michael Leber (Booklist)

“Binstead’s Safari is not about lions or their position as kings. Rather, it employs its fantastic lion imagery to reveal the wild darkness of humans, to uncover the horrifying ways in which humans turn on each other. Men against women. The colonial imagination against the indigenous one … Binstead’s Safari is a strange masterpiece in which the suspenseful and potentially horrifying are balanced by campy comedy. In Ingalls’s fiction, we returned to the essential unknowability of the fantastic. Yet for all its puzzle-ness, the novella resists encapsulation, resists being named and pinned down. As a particularly intricate and rich cipher, the novella is better experienced than described. Is it a contemporary fable about feminism and anti-colonialism, or an elaborate joint hallucination of a couple whose marriage is falling apart? The fragile beauty of the truly fantastic in literature is such that it disintegrates if you try to break it down with too violent a logic.”

–Anita Felicelli (On the Seawall)

*

The Pearlkillers: Four Novellas (1986)

“In the first of these refined tales of violence, a woman’s three husbands die, one after another. In the second, four men and a woman are murdered, and in the third, three old women and their maid. The fourth contains a positive orgy of death by shipwreck and various acts of God and man. An element of fantasy, subtle in the first tale, increasingly strong in the others, preserves the mayhem from vulgar realism, and the reader from an unduly emotional response … Though it might seem a curious subject for a woman writer, masculine psychopathy does, perforce, interest women. Ms. Ingalls is an experienced writer of novels and stories, and her performance here is immensely skillful, reminiscent of the best film thrillers. The tale might be considered a cautionary one, if the combination of the cool tone with the extreme brutality of the events described did not make any search for a moral purpose or purport, in such a narrative, appear naive … Is the reader expected to take the lurid events lightly, as playful make-believe, or seriously, as a lesson in psychotic self-destruction? The difference is essentially ethical. Perhaps it is not one that the author would make or care to have made about her artful and blandly nightmarish tales.”

–Ursula K. Le Guin (The New York Times)

“Her characters all bear the mark of Cain: They are innocents (no matter that some may be killers) who are swept along through tepid, flat circumstances until suddenly all hell breaks loose, and the Furies erupt to claim their prey … In Ingalls’ world, civilization and even sexuality itself are just loose flimflams and charades that are masquerades for much darker, demonic powers. Sooner or later, reality begins collapsing backwards into atavism and prehistoric ritual, and when that happens, we know we are rushing headlong toward the final, awful denouement. In her best work, Ingalls is as monochromatic as Edgar Allan Poe, going straight to her target with the same ease and surety as an arrow skims to its bull’s-eye. Her world view is more complex than Poe’s: Where Poe simply demonstrated the inevitable eruption of the dark powers, Ingalls has an alarming vision of the parasitical and parricidal relation between the present and the past. And just as Poe’s craft was exactly suited to the conventions of the short story form he invented, so Ingalls’ vision is exactly suited to the length and scope of the novella form. This is because, like Poe, Rachel Ingalls is more than a master storyteller: She is also a superb artist.”

–William Packard (The Los Angeles Times)

“Again, Ingalls looses some twilit monsters of the mind—directly from our most snug and most smug attitudinal rituals. Like the works of Isak Dinesen and John Collier, Ingalls’ eerie tales, marked by a mordant humor, have the dark gloss of the surreal, behind which the characters—just ‘ordinary people’—learn to keep afloat on some increasingly enticing infernal winds … Enigmatic, occasionally brooding, each tale with a singular twist—this is shivery entertainment.”

*

You might also like…

This excerpt from Mrs. Caliban

Hot Sex With Sea Monsters: A Comparative Study of Mrs. Caliban and The Shape of Water

This Thing of Darkness: An Interview with Rachel Ingalls

Daniel Handler on the Best Writer You Don’t Know: Rachel Ingalls