There are few things the literary community relishes more than the appearance of a polarizing high-profile book. Sure, any author about to release their baby into the wild will be hoping for unqualified praise from all corners, but what the lovers of literary criticism and book twitter aficionados amongst us are generally more interested in is seeing a title (intelligently) savaged and exalted in equal measure. It’s just more fun, dammit, and, ahem, furthermore, it tends to generate a more wide-ranging and interesting discussion around the title in question. With that in mind, welcome to a new series we’re calling Point/Counterpoint, in which we pit two wildly different reviews of the same book—one positive, one negative—against one another and let you decide which makes the stronger case.

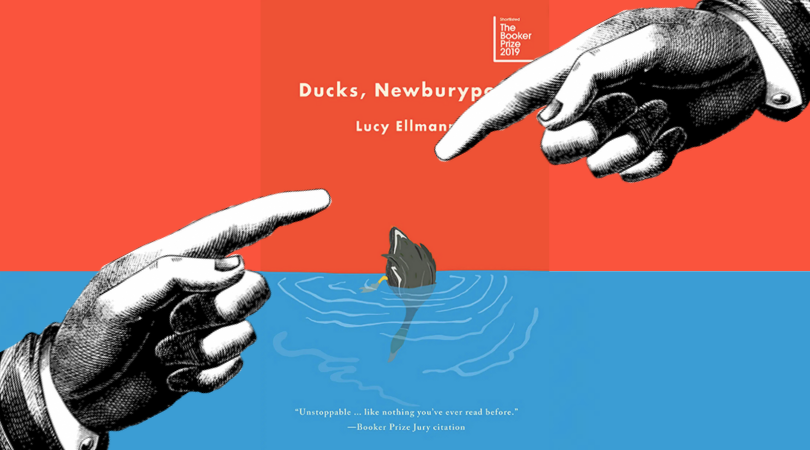

Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport has taken the literary world by storm. It was shortlisted for this year’s Booker Prize, and, despite its hefty size, it seems like everyone wants to get their hands on it (Seriously, it’s out of stock at all the bookstores we’ve been to!) This one-thousand-page novel, unspooling in what is essentially one sentence, relays the stream of consciousness of an Ohio housewife. She flits between topics like Trump, gun violence, climate change, animal cruelty, and SpaghettiOs—and paints a portrait of contemporary America in the process.

The reviews have been, for the most part, absolute raves. Ian Sansom in The Guardian calls it a “triumph.” Katy Waldman in The New Yorker tells us that, “Much of the pleasure of this book is the pleasure of learning a puzzle’s rules.” In The Financial Times, Catherine Taylor remarks, “In Ducks, Newburyport Ellmann has created a wisecracking, melancholy Mrs Dalloway for the internet age.” Sebastian Sarti of Chicago Review of Books praises it as, “an effervescent novel…that encompasses a contemporary life by underscoring the material language that composes its consciousness.”

But of course it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. Kirkus says, “All this memory and reflection and agonizing comes in an onrushing flow of language that slips often—deliberately, it seems, but too obviously—into games of throwaway word association.”

Today, we’re looking at Parul Sehgal’s very positive New York Times review, which notes, “[Ducks, Newburyport] feels dense at first, a bit like drowning, without a period or paragraph break in sight. But a rhythm asserts itself and a structure, musical and associative.” In the other corner, we’ve got Scott Bradfield’s more mixed Washington Post review, which states, “Maybe we don’t need reminding what a mess we’re drowning in.”

What do you say, dear reader? Ready to dive in?

*

When you are all sinew, struggle and solitude, your young—being soft, plump, vulnerable—may remind you of prey.

“… requires patience and good cheer; otherwise you may not find your way through the continual and often exasperating redundancies that occur on every one of this book’s pages … The novel bombards its reader with info-bites—funny, sad, thoughtful, angry, confused, apocalyptic—with the ceaseless regularity of a combustion engine. Sometimes the repetition can drive a weak mind (like mine) a bit mad; but every time I was about to put the book down and walk away, I would be struck again by the protagonist’s bright, unpretentious, ironic voice … The narrative voice that drives this inexhaustible and exhausting accumulation of ‘facts’ is surprisingly interesting, engaging and inventive … Ellmann’s fictional world reminds us, over and over, that yeah, we get it. We live here, too, lady. We feel engulfed, every day when we wake up and every night when we go to bed. Engulfed, engulfed, engulfed. The world just doesn’t quit, does it? … My biggest failure as a reader of Ducks (and I’ll have to leave it to posterity to decide if this is my failure or the book’s) was in trying to discern a ‘front story’ … maybe we don’t need reminding what a mess we’re drowning in. Or maybe it’s just too late.”

–Scott Bradfield, The Washington Post

“… seems designed to thwart the timid or lazy reader but shouldn’t. Timid, lazy readers to the front! Ellmann’s unnamed narrator, a mother of four living in Ohio, has a cutting power of observation and a depressive charm … This book has its face pressed up against the pane of the present; its form mimics the way our minds move now: toggling between tabs, between the needs of small children and aging parents, between news of ecological collapse and school shootings while somehow remembering to pay taxes and fold the laundry … feels dense at first, a bit like drowning, without a period or paragraph break in sight. But a rhythm asserts itself and a structure, musical and associative … Never mind the mountain lioness subplot, the novel’s most startling feature is the marriage at its center: the narrator’s life with her husband, their steadiness and mutual enchantment, their kindness to each other. In literature, sometimes nothing seems so extraordinary as ordinary happiness … The capaciousness of the book allows Ellmann to stretch and tell the story of one family on a canvas that stretches back to the bloody days of Western expansion, but its real value feels deeper—it demands the very attentiveness, the care, that it enshrines.”

–Parul Sehgal, The New York Times

Deep Dive:

Here’s what Lucy Ellmann said in response to some of the whiny criticism around her book.

Here’s a conversation with Lucy Ellmann.