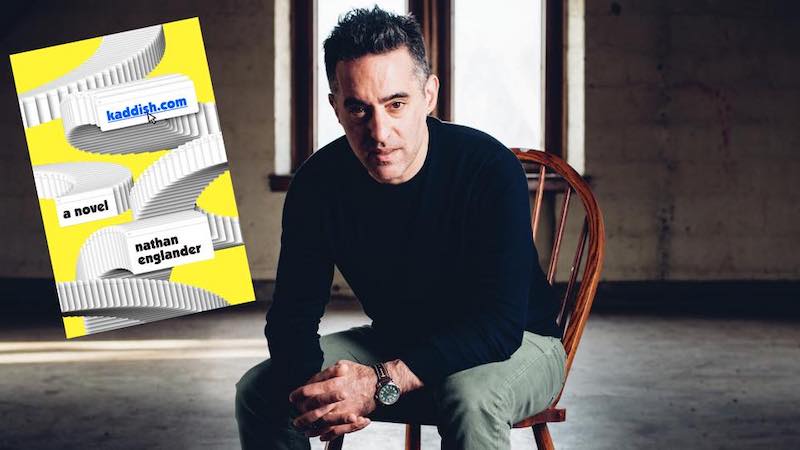

Nathan Englander’s novel Kaddish.com is published today. He shares five books on transformations (of worlds, of people, some of them with journeys slipped in).

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

I read The Handmaid’s Tale after the TV show, decades after it was already a super famous novel, but for me it was brand new, and a dark, depressing joy to read. You have a world transformed and then you have Offred navigating within it, using memory as a kind of guide. Separately, the epigraph to the book is just insane. That leap shouldn’t work, it should bump us, but somehow it fits perfectly and offers retroactive hope.

Jane Ciabattari: Can you tell us more about that epigraph?

Nathan Englander: Do you have to give spoiler warnings for books from 1985? If so, spoiler alert! The epigraph is from a symposium on Gileadean Studies in the year 2195. And it’s amazing. Amazing that Atwood can make that jump, that it doesn’t jar the reader, that she can so perfectly mimic academic symposium-tone, and that we find out there is a distant future where the terrible reality of the novel is history. It leaves us hopeful.

Blindness by Jose Saramago

I must have read Blindness twenty years ago, but the story stays with me. I just love the quiet, tectonic shift of the opening—if something can be quietly tectonic. It just zooms right in on city life, on a busy corner, a streetlight changing and a car that doesn’t go. And then there’s the confused man behind the wheel, who mouths the words, “I am blind.” The collective change, and the terrifying plague of blindness that strikes their world is just a hugely powerful metaphor.

JC: It is a relentless, disturbing novel. And yet….don’t you think he ends up making it somehow uplifting? How does that happen?

NE: I want to answer this as a craft question, as opposed to talking about, say, the turns the end of the book takes. I think if an author wants to wrestle with the big questions in their writing, they need to be able to strike that exceptionally delicate balance you’re asking about. They need to be able to strike the world blind, as in the Saramago, or do all the dastardly things that take place on the mostly not-too-cheery list I’ve compiled, and, while asking us to reflect on certain massive existential ideas or terrible moments in history, they need to leave us feeling hopeful, and optimistic—if that’s where their hearts lie, and if, in their stories, there’s any hope of redemption.

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

In the Underground Railroad, it’s that step from the bleakly, terribly real to the surreal that sets up a transformation that has to be as big as they come, the one from slavery to freedom.

JC: Whitehead’s novel redefined history in such intriguing ways, opening pathways for many books to follow. Do you have favorite sections?

NE: I have an instantaneous answer to the question. But I’d like to swap out the word ‘favorite’ because the scenes that come to mind (as with so many parts of the book) are painful. So I’ll single it out as a singularly powerful stretch, instead. And I’m talking about the part of the book where Cora interacts with Martin and Ethel, including the Friday Festival, and the super short and super poignant Ethel chapter.

Waiting for the Barbarians by J. M. Coetzee

I was just knocked out by Waiting for the Barbarians, both as a read, and as a timely cautionary tale. If I’m supposed to be talking about transformations, the rise and fall and sort-of redemption of the Magistrate is something (terrible) to behold.

JC: Colonel Joll and his secret police define the nomads the Magistrate has known as peaceful throughout his life as barbarians about to attack, and go on to torture and brutalize them. It’s a chilling scenario, and yes, timely. How do you think Coetzee is able to craft the Magistrate’s gradual change through suffering and make it so effective?

NE: By letting fiction do one of the things it does best, muster empathy. The Magistrate is our eyes and ears; he’s our person in that world, our literal point of view. We share a consciousness with him, and that’s what keeps us in his world, whether he’s attempting to put things right, or playing his own role in the oppression of the Empire. And, after a biblical-level amount of suffering, that’s what allows Coetzee to floor us with the Magistrate’s final transformation.

The Little Disturbances of Man by Grace Paley

I just love Grace Paley stories. And if I’ve chosen a lot of gigantical transformations that shake up whole societies, Paley can take the wind out of you with the personal, private shift. My favorite example is “Goodbye and Good Luck,” that’s the one I read again and again. That story makes me cry every time.

JC: Rosie decides to “live for love,” in contrast to her mother, who “married who she didn’t like. He never washed. He had an unhappy smell, he got smaller, shriveled up little by little, till goodbye and good luck.” This story chronicles her thirty-some-year relationship with an actor she meets in her teens. Can you point to a line or a paragraph where she reaches a tipping point?

NE: She’s already past the tipping point when we get to the title. ‘Goodbye’ is the first word we see. It’s her crossing that line that is the very impetus for the story—that’s what keeps it so pressurized. Every bit of it is an act of release, a declaration of freedom. The transformation is already there. She’s done being “Poor Rosie” at the start. We meet her when she’s past the point of no return.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·