Is there anything more thrilling than digging into a just-released book by an admired author?

In Context is a new essay series in which critic Lori Feathers looks at the latest work of fiction by an established writer within the context of their overall body of work. Lori explores her subject’s oeuvre by identifying the writer’s themes and cultural resonance, discussing their literary technique, and revealing how the new book builds upon, or diverges from, their previous work.

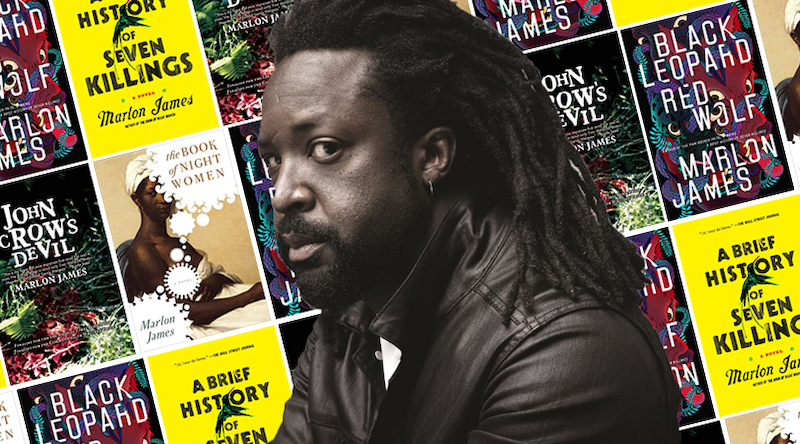

This week, Lori considers the novels of Man Booker Prize-winner Marlon James, whose latest, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, hits shelves today.

*

Marlon James’ novels are paeans to the ostracized, the disenfranchised—those who, whether by birth or circumstance, find themselves on the “outside” and, as a consequence, feel most acutely both the hunger for companionship and the hardship in obtaining it. His fiction possesses a timeless relevancy in its power to expand our empathy for those who ache with the universal need to feel accepted.

This week marks the release of James’ fourth novel, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, a work that affirms his place as one of our most talented living authors. The novel takes readers to a fantastical, other-worldly land populated with beings, some human and others supernatural, whose complex inner lives unspool within a coming-of-age adventure involving the quest to find a missing boy marked to be a future king.

John Crow’s Devil, James’ remarkable debut, was first published fourteen years ago. Faulknerian in its layered narration and theme of biblically-invoked retribution, it depicts a Jamaican town upended by the sudden appearance of a messianic preacher, the “Apostle.” James’ follow-up, The Book of Night Women, unfolds during the Jamaican slave rebellions of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Lilith, a mixed-race slave, is torn between fidelity to her slave “sisters” and their plot of violent insurrection against whites, and the Irish slave master who makes her his concubine and with whom she unwillingly falls in love. A Brief History of Seven Killings, James’ third novel, won the 2015 Man Booker Prize. A polyphonic tour de force that explores Jamaica’s gang wars of the 1970s, the book centers on the attempted murder of “the Singer,” the alter-ego of the musician Bob Marley, and reveals the roles of international drug syndicates and the CIA in fueling the island’s terrible gang violence. With Black Leopard, the first book in a highly-anticipated trilogy, James makes a decisive shift to the fantasy genre and further bolsters his credentials as an artisan of multifarious forms.

James rejects the comfort of reworking narratives and techniques that previously earned him accolades. With each subsequent novel, readers’ expectations regarding plot, characterization, and narrative construction are likely to be confounded. Yet within the range and virtuosity of his work certain thematic concerns and storytelling techniques surface, and these are the trademarks of James’ literary oeuvre.

James’ fertile imagination is firmly rooted in his Afro-Jamaican heritage—each of his three previous novels is set in Jamaica, and while Black Leopard’s story takes place within various imagined African kingdoms, its myths, rituals and Patios-infused speech are that of the author’s native Jamaica. Many of Jamaica’s slaves came from Ghana, and they brought stories of the old ways and traditions of their Ashanti ancestors, notably the practice of sorcery (obeah) and witchcraft (myal), and the custom of female succession of tribal leaders. James uses this heritage to tremendous effect. Each of his novels features female characters who possess near-mythical strength demonstrated by their wisdom, inner fortitude and, in some cases, supernatural powers. The firm intentions of these women confront their own fractured identities: they are in a continuous, private battle to negate those parts of themselves bound-up in shame and perceived inferiority. Church-going Lucinda (John Crow’s Devil) is torn between her “day” and “night” selves—the good Christian and the vindictive practitioner of black magic. Lilith’s desire to be “seen” by her white subjugators (The Book of Night Women) shames her and incites the resentment of her fellow slaves. Nina (A Brief History of Seven Killings) is obsessed with leaving Jamaica and, when she succeeds, tries to eviscerate her Jamaican roots by changing her name and lying about her history. Finally, Tracker (the hero of Black Leopard) comes-of-age alienated from family and tribe and adjusting to being genderqueer. James’ narratives explore how the inherited signifiers of sex, race, and tribe preordain identity, while at the same time he dismantles the notion that these determiners are binary and immutable.

James mines oral story-telling traditions to reveal his plots. Characters testify about significant happenings as actors, witnesses, or reciters of stories passed down. There is a grandeur to these oratories, language that resonates with the ancient timbre of biblical verse and Greek tragedy. The stories hold historical memories within which the actors attempt to find meaning for their dismal circumstances. At the same time, stories are shared again and again to sustain hatreds, mythologize persons into heroes, and nurture hope against suffering. Indeed, the intentional manipulation of others through the telling of stories is a recurring motif in James’ novels, as in Seven Killings, for example, where a rumored peace between rival gangs is used to incite violence, or in John Crow’s Devil, where accounts of the Apostle’s miracles are spread in order to build a cult of personality around him.

James’ reliance on the spoken word also distinguishes his work in another sense: he is masterful at writing dialogue. The conversations, for the most part, are in the author’s Jamaican Patois vernacular and use staccato-ed speech that exerts a syncopation laden with rap, pulp film, and literary influences. The dialogue is fun and often very funny. It is also intentionally disorienting—the cacophonic voices mirroring the chaos of the violence enacted on the page. Despite creating intermittent confusion, the conversations expose the characters’ humanity, imprinting emotional connections for the reader that are stronger than those that arise from descriptive characterizations alone.

In James’ milieus clans wage war against clans, and characters are fated at birth to join the side that will accept them; remaining neutral would be an act of betrayal. In each of the novels protagonists undergo crises of conscience that produce fissures in their felt allegiance to the group, a circumstance that provides a springboard for James to explore the near-instinctual need to belong and how it shifts an individual’s axis of morality. It is at this crossroads of belonging and immorality that characters must decide whether to subsume personal convictions to the violent acts of the collective, whether that means joining fellow gang members in the attempted murder of the Singer, or participating in the brutal, public lashings of neighbors at the Apostle’s behest. All the while James allows us to see the constraints on his characters’ personal agency. In many instances it is impossible for them to leave their group or act outside its interests without meeting certain death, as is the case with the gang members in Seven Killings and the insurrection plotters in Night Women.

By showing that personal empowerment is a confluence of fate, identity, and agency, James’ novels become existential reflections on life’s purpose. Some believe that their life is an instrument, whether used by a reactive god or their group’s agendas, for a cause greater than the self. Such is the case with the gang members in Seven Killings for whom inflicting vengeance upon a rival gang is purpose enough.

At the conclusion of Black Leopard Tracker surmises that while the various stories we pass down always contain a purpose, the real story—life—has no purpose. James leavens the hopelessness of this somber realization by granting his protagonists the grace of occasional companions in their life’s journeys, imperfect friends who disappoint with their self-interestedness and betrayals yet nonetheless, at least momentarily, make them feel accepted. And that is a feeling that no amount of sorcery or witchcraft can replicate.