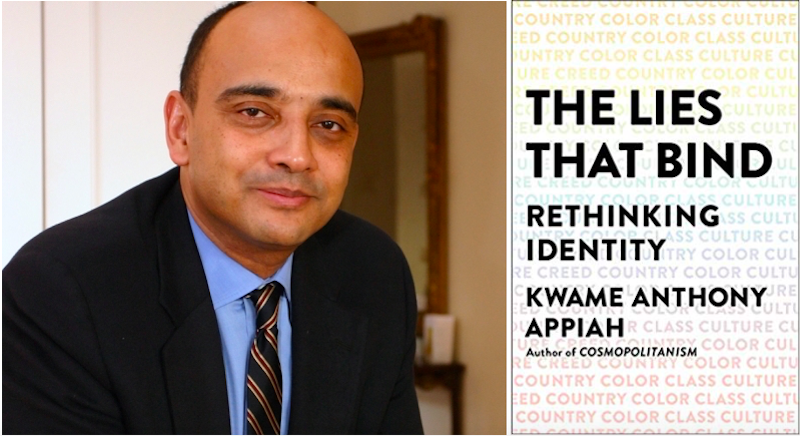

Kwame Anthony Appiah’s new book, The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity, is published this month. He shared his list of five books about individuality and identity with Jane Ciabattari.

*

On Liberty, John Stuart Mill

In Chapter Three, “On Individuality as one of the Elements of Well-being,” Mill offers an impassioned defense of the idea that each of us has to “find out what part of recorded experience is properly applicable to his own circumstances and character.” It’s his balanced sense that each of us is both particular and distinct and yet, at the same time, shaped by our social circumstances, that makes this discussion of individuality so inspiring. Mill’s discussion anticipates the best contemporary thoughts about selfhood. “Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing.”

Jane Ciabattari: Reading these passages from On Liberty is oddly emotional, as I am pained by the fact we seem to be situated in a binary time, with the more spacious sense of individuality which I prize on the wane. Do you believe the complicated relationship between individuality and social identity shifts in cycles? Are we due for another shift?

Kwame Anthony Appiah: I’m not sure that there are cycles, but there are certainly historical shifts in the salience of different sorts or dimensions of identity. Mill was worried about a kind of flattening of the social world in which increasingly uniform and universal modes of education combined with the pressure to conform—the tyranny of the majority—produced people who were more and more difficult to distinguish from one another. So On Liberty celebrates not just genius but also eccentricity. He thought that we all profit from both, even when we are challenged or threatened by them. But above all he thought that each of us should make our own lives. He says: “If a person possesses any tolerable amount of common sense and experience, his own mode of laying out his existence is the best, not because it is the best in itself, but because it is his own mode.”

There are actually two important ideas in Mill. First, that we are different and so need different circumstances to flourish. But second, that what matters in a life depends, in part, on the choices of the person whose life it is. One problem in our time is that the first of these thoughts can lead people to say, “This is my identity, so I must live it out.” But that can actually make your life less your own, and drive you away from finding your own particular “mode.” Talk of authenticity—racial, ethnic, religious, national—can actually be a straitjacket, because the authentic self turns out just to be the expression of some group. And that’s probably the worry that makes you think there’s something moving in Mill. So I guess it’s worth pointing out that one can take up a racial identity, say, and use it to make one’s own original life. It’s just that it’s important to make sure that you tailor the off-the-shelf outfit to your own developing self.

JC: To step aside, slightly, I’m wondering if Mill’s sense of individuality can apply to the distinguishing characteristics of the books on this year’s longlist for the Man Booker Prize? As chief judge, you noted “All of these books—which take in slavery, ecology, missing persons, inner-city violence, young love, prisons, trauma, race—capture something about a world on the brink.”

KAA: Well, one of the reasons for caring about individuality comes from a thought that is found in Mill but really more fully played out in Nietzsche, which is that the central ethical project—making one’s life—is to be seen as an exercise in imagination, in creativity. One’s life is one’s greatest work, so to speak. And so, in lives as in art, we prize the original, the thing that is unlike anything else. I think this idea can be overdone both in lives and in the arts! But it does strike me that my fellow judges and I this year found works that were enormously formally diverse, diverse in location and subject matter, and also profoundly original: not like most of what has come before in the history of the novel, even though we inevitably read them with earlier books in mind. Harold Bloom taught us to see literary history not as a matter of a happy acceptance of influences but as a matter of Oedipal antagonisms between one generation and the next. And surely serious readers are engaged by work that goes beyond what’s already been done.

Le rouge et le noir, Stendhal

It’s really amazing that Stendhal chose as the protagonist of one of the first modern “psychological” novels, a young working-class man who manages to rise through the class system of France … and then fall spectacularly as well. Julien Sorel is so driven by his ambitions, conscious always of the fragility of his new position, and hypersensitive to how he appears to others, even the women with whom he sometimes thinks he’s in love. He’s got an interior life—Stendhal knows how to give him that—but he’s so shaped by the identities imposed on him by his social world, that he seems almost unaware that the life he is living is his own.

JC: His hypersensitivity to his persona and his awareness of how quickly his life could crumble create an ongoing struggle for individuality that keep Julien off-kilter. Do you have a favorite section in which Stendhal shows us Julien’s interior in conflict with those social identities?

KAA: Very early on in the novel, when he first arrives chez M. and Mme. Rênal, his new master has him dressed him in fancy clothes. And he says, “Sir, … I feel awkward in my new clothes. I am a poor peasant and have never worn anything but jackets. If you allow it, I will retire to my room.” But what he’s actually covering up here is that he’s just presumptuously kissed the hand of his mistress! Is he just playing the “poor peasant”? Hard to say. Soon, he’s being called “Monsieur,” and he likes it. But Stendhal also tells us “As for himself, he felt nothing but hate and abhorrence for that good society into which he had been admitted; admitted, it is true at the bottom of the table, a circumstance which perhaps explained his hate and his abhorrence.”

Song of Lawino, Okot p’Bitek

I’ve always loved this brilliant evocation of the life of Lawino, a traditional Acholi woman in Uganda, struggling to make sense of the world of her husband, Ocol, alienated by his colonial education, and infatuated with a “new woman,” who, like him, has a life shaped by modern literacy.

Listen, my clansmen,

I cry over my husband

Whose head is lost.

Ocol has lost his head

In the forest of books.

JC: And she continues:

And the reading

Has killed my man,

In the ways of his people

He has become

A stump.

Lawino laments her husband’s shift to Western values, becoming a Christian, getting a Western education at Makerere University, changing his name, trading in the traditional sense of time (he now schedules his life according to a grandfather clock whose ”large single testicle / Dangles below”) and reading books instead of listening to stories. She is embedded in the ways he now considers backward. Okot p’Bitek’s book-length poem captures a moment when a husband’s focus on reinventing his social identity denies his first wife’s individuality, and so he moves on. I’m wondering if you think there are parallels in today’s world?

KAA: Well, I think that the issue of sloughing off older connections because one is developing a new identity is very real to many of the (too few) first-generation students in our classes in college. They have to figure out how to handle the cultural capital they’re earning—the development of more formal academic modes of speech and writing, the ability to connect their experiences with high literature, to read the life around them through social theory—while not distancing themselves from the friends and family who don’t have those things. They have to figure out how not to seem condescending … while very often feeling that they really have been let into a superior kind of understanding (and knowing that those they’ve “left behind” suspect that may be true as well). And if they fail to keep this balance, then they’ll act the sort of way Ocol acts towards Lawino. I think we don’t sufficiently acknowledge how hard this balance is to achieve: college education, cosmopolitan reading, opening one’s mind to unfamiliar ideas, inevitably shapes you into a new kind of person … unless it fails! And that new person is different from people who don’t have those intellectual experiences, which can come, of course, through reading and thinking on your own, and so without a college degree.

I know someone who grew up in London’s working-class East End, learned to box in a boxing club where those legendary gangsters the Krays hung out, and is now a very successful college-educated financier, living mostly outside the United Kingdom. When he was planning to send his sons to a famous English boarding school, one of his childhood friends pleaded with him not to do it: “Send them to stay with us and they can go to school in the neighborhood,” he said. That way they could have a family life. These friends of his had not been to college, didn’t see the point of it, and haven’t sent their children off to college, either. So it wouldn’t have made sense to tell them, for example, that these boys had a better shot at college if they went to a private school. (And, indeed, two of them went to Cambridge, one to Oxford.) Class identities and education are intimately interlaced, in ways that generate these distances between people’s identities. The multigenerational family life of an established East End family is a precious thing … and the welfare state, at its best, has made the lives of these people more prosperous and comfortable than the lives of their grandparents. But we’ve made a world where keeping that rich family life is very hard if you aim for the world of the educated middle classes. And you don’t have to be a snob to decide that it’s worth it. What’s snobbish is failing to see what’s good in the lives of those who make the other choice.

Nervous Conditions, Tsitsi Dangarembga

This book has a famous first sentence. “I was not sorry when my brother died.” Okot p’Bitek’s Lawino is a traditional woman struggling with colonial modernity; Dangarembga’s Tambu, in this novel, is at the leading edge of that world, achieving success in the new missionary schools and chafing against the limits set on the dreams of women in her society. By the end, you know why she begins that way. And so, by the end, it has earned this beginning.

JC: Tambudzai’s sense of individuality is powerful as she attends a mission school in the late 1960s, during the waning years of colonialism in what was then Rhodesia, and the build-up to the independent Zimbabwe. Her voice is both emboldened (she has an opportunity to rise above her class and gain an education, rare for a young woman in her circumstance) and frustrated as she encounters limits of race and gender. Do you see this novel as a breakthrough? In what ways?

KAA: I think it’s a marvelous novel on so many levels. But perhaps the big breakthrough is that the Lawino figures in this book, the women who are being left behind by the new forms of cultural capital, are treated with as much sympathy as the women who are on that leading edge—women like Tambu, herself, or her aunt, Maiguru, who’s married her uncle, the head of the mission school, and has a masters degree, or her cousin, Nyasha, who’s been educated in England for a while. At the end of the novel, Tambu says, “the story I have told here, is my own story, the story of four women whom I loved, and our men, this story is how it all began.” And the “it” there is the questioning about the role of women and of the “native” in her society. The title comes from a remark of Fanon’s: “the condition of native is a nervous condition.” And Tambu’s cousin, Nyasha, is literally driven into mental illness—anorexia—by her pursuit of individuality with tools that most of those around her don’t make sense of. This is a girl who wants to read Lady Chatterley’s Lover in a very conservative Christian mission school! In the Song of Lawino you sort of have to chose between Lawino and Clementine, Ocol’s new “modern” wife who “aspires/To look like a white woman.”

The Remains of the Day, Kazuo Ishiguro

Mr. Stevens, Ishiguro’s protagonist, doesn’t believe in individuality, affecting to bury himself in his vocation as a butler, denying himself the right to an independent judgment of the doings of those he regards as his betters. “Let us establish this quite clearly: a butler’s duty is to provide good service. It is not to meddle in the great affairs of the nation … those of us who wish to make our mark must realize that we best do so by concentrating on what is within our realm.” The result, of course, is that he ties his fate to a worthless “master.” And yet Stevens, with his dogged commitment to the profession he has chosen, has always struck me as someone who demonstrates the power of individuality as an ideal despite himself.

JC: As you wrote to me, “with The Remains of the Day, we’ve got an obvious picture of heteronomy (the butler subordinates purposes to those of his master’s), and yet the butler, and the butler alone, has mastery of his craft, his vocational identity (the master wouldn’t know the niceties of what butlerian excellence consists in).” The butler is encased within a class system as confining as the “great, high walls” Constantine Cavafy describes in his poem “Walls,” which you quote in your new book. How might that class system affect Ishiguro’s protagonist if he were alive today?

KAA: One of the lessons of Stevens’s life is just how much the possibilities of an identity (in his case as a butler) can depend on the availability of structures and institutions. Without the world of the great country houses, you can’t be what he wants to be. And the house he has worked in for so long is now—at the end of the day—in the possession of an American who doesn’t understand the world he’s bought into. You need others who share your understanding to make any social identity work. So you can pretend to be the sort of butler that Stevens was now. But you can’t actually be one. It’s like the point that the philosopher Ian Hacking made about Sartre’s garcons-de-café in Being and Nothingness: you can’t be one of those without the conventions of those Parisian cafés.

The point about Walls—and why the Cavafy poem is so on point—is that they’re necessary (as identities are) but they can also be imprisoning. As I say towards the end of The Lies that Bind, “… the problem is not walls as such but walls that hedge us in; walls we played no part in designing, walls without doors and windows, walls that block our vision and obstruct our way, walls that will not let in fresh and enlivening air.”

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.