Is there anything more thrilling than digging into a just-released book by an admired author?

In Context is an essay series in which critic Lori Feathers looks at the latest work of fiction by an established writer within the context of their overall body of work. Lori explores her subject’s oeuvre by identifying the writer’s themes and cultural resonance, discussing their literary technique, and revealing how the new book builds upon, or diverges from, their previous work.

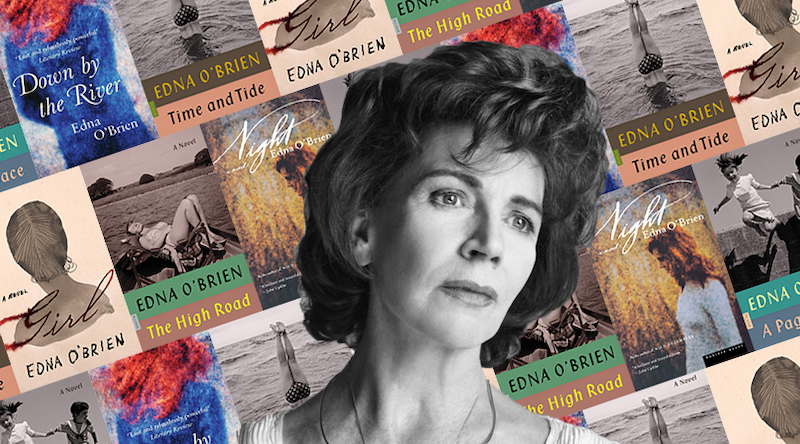

This week, Lori considers the novels of the iconic Irish feminist writer, Edna O’Brien.

*

Edna O’Brien is a literary marvel. For sixty years she has been creating stories that give voice to women fighting to overcome the circumstances into which they were born. In the early 1960s O’Brien’s portrayals of rebellious young Irish women were deemed too risqué in her native country, where for a time her books were banned. This week her latest novel, Girl, is being published in the US, capping a career remarkable not only for its longevity and prolificacy (seventeen novels, in addition to short story collections, children’s books, poetry, plays for theater and screen, literary biographies and memoirs), but also for the critical acclaim it has garnered. O’Brien is regularly lauded by critics as one of the finest writers of our time, a status affirmed by her numerous literary awards and legions of admiring readers.

The eighty-eight-year old author currently lives in England, as she has done most of her adult life, but her soul resides in the pastures and villages of the west of Ireland, a land that she depicts with exquisite detail and texture that is nourished by the recollected impressions and sensations of her upbringing. Given that Ireland, and often London (the Shangri-La for O’Brien’s farm girls), are the settings for most of her novels, and that nearly all of them feature Irish-born protagonists, Girl seems at first to be a surprising departure. The novel takes place in Nigeria and concerns a schoolgirl who is kidnapped by Boko Haram. However, like O’Brien’s previous novels, Girl resounds with the author’s true métier—the emotional dissonance between mothers and daughters.

In Girl, Boko Haram soldiers overtake the dormitory of a secondary school and abduct dozens of girls, among them Maryam, the novel’s narrator. The kidnapping and transport of the girls to the jihadis’ encampment is just the beginning of many months of brutality and sexual violence that the girls suffer at the hands of their captors. Throughout her imprisonment Maryam longs for her mother and dreams of being returned to her. Instead she is repeatedly raped and as a result, soon becomes a mother herself. Though Maryam and her mother are eventually reunited, they are never truly reconciled because the shame of Maryam’s captivity profoundly and irrevocably corrupts their relationship.

A haunting disquiet pervades O’Brien’s novels. The daughters in these stories absorb the memories of their mothers and female ancestors. This inherited memory is acquired in the womb and from the land—the family’s native soil is a reliquary of ancestral memories—and grafted onto the daughter’s self-identity, undermining her agency:

“…sooner or later we are brought back to the dark stew of ourselves and the ancestry before us, back to the midnight of the race whose sins and whose songs we carry.” (Time and Tide)

There is a fatality in the recognition of this inheritance as it fosters a poisonous co-dependency between mother and child. O’Brien reveals the “carnivorousness” of motherhood, the insatiable need to retain primacy in her child’s life. The novels burrow into the dark, festering anger and unspeakable thoughts that overwhelm the mother-child relationship and culminate in an irreparable alienation:

“A catalog of grievances on both sides was aired, and even as she heard them or voiced them, she thought how muddled it all was, how far removed from the nub of the matter, which was that the love they once had, the sweet vital reserves of love, had vanished, disappeared like those streams that go underground without leaving a trace.” (Time and Tide)

Yet despite (and even because of) this emotional estrangement and the physical distance established when the daughter leaves home, mother and daughter remain completely preoccupied with one another. It is a fixation so persistent that even death cannot vanquish it, or at least that’s how it seems in dreams:

“She had precepts written out on a slate, in gold no less, like the Writ of Moses, stipulating further how I must live out the remainder of my life…Then she started to infer that she would be resident here for all time, keeping a total watch…counting the number of cigarettes I smoked, my alcoholic intake, the knaves that I brought home…I had the most terrible feeling, the most shocking realization: you cannot kill the dead.” (Night)

Each one of O’Brien’s Irish farm girls grows up determined to make a life for herself that is markedly different than the one in which she was raised. She runs off to the city; attaches herself to older man who is sober, measured, and sophisticated—in short, a gentleman rather than a rube like her father—and, tries to ignore the rules of her Catholic upbringing. In this way the young woman succeeds in forging a life that contradicts her mother’s in nearly every way, and yet she is filled with shame and guilt. She feels at once inadequate to her new life and ostracized from any possible support or encouragement she might once have availed herself of in the old. Over time the “gentleman” assiduously fosters her self-doubt as a way of reaffirming his own superiority. He humiliates and denigrates her for her father’s drunkenness and her family’s poverty, ignorance, and Catholicism.

At the same time the girl’s mother, left behind in the wake of her daughter’s desertion, is ashamed of her. A stigma attaches to the errant girl, and there is the perception that she has been corrupted by the outside world. This stamp of acquired “foreignness” is especially acute for Maryam, the kidnapped student in Girl. Upon returning home to her village she observes,

“They all looked at me strangely. The mien and wildness of the forest hovered over me.

…I felt a freak. I could read their minds, by their false smiles and their false gush. I could feel their hesitation and worse, their contempt.”

Even more severe is their reaction to Babby, Maryam’s infant daughter conceived in rape, whom the community regards with a mixture of fear and scorn. The village elders believe that they have the right to determine Babby’s fate, and they argue over whether she will be sent away or permitted to stay. They condemn the baby for her “bad blood” and hate her for being an emblem of their impotence against Boko Haram. The way that evil insinuates itself into a society and disrupts its cohesion is a recurring theme for O’Brien; in The High Road, Wild Decembers, and The Little Red Chairs, evil is personified in a stranger who moves into an isolated, close-knit community and destabilizes it. Throughout Girl, Maryam’s own feelings for Babby are conflicted. She vacillates between possessive, maternal love and furious rejection because Babby represents both her violation and her imposed motherhood.

Ambivalence about being a mother is a motif in many of O’Brien’s novels, even for women who are in consensual, long-term relationships. Often the anxiety about raising a child is a legacy of the woman’s fraught relationship with her own mother. Other times the wariness arises from an uneasy awareness of her own selfishness:

Life, after all, was a secret with the self. The more one gave out, the less there remained for the center—that center which she coveted for herself and recognized instantly in others…where the true worth and flavor lay.” (Girls in Their Married Bliss)

This ambivalence regarding motherhood is reflected in the way that that author handles the subject of abortion. Right from the beginning of her career, O’Brien has been unafraid to portray women who undergo abortions as a means to preserve their autonomy and aspirations. And for some (like Baba in The Country Girls trilogy—a psychologically compelling examination of lifelong, female friendship that is every bit as engrossing as Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend novels), practical considerations outweigh religious ones. In her 1996 novel Down by the River, O’Brien confronted the Catholic Church’s stance against abortion head-on with the story of a young incest victim whose pregnancy becomes a rallying cry in a very public tug-of-war between pro-choice activists and the Church.

The Catholic faith is impressed upon O’Brien’s Irish girls from an early age, and they carry the Church’s moral doctrine into adulthood. When the women sin, whether it be in thought or action, their consciences plague them, and they mortify themselves in the hope of being cleansed of their transgressions.

“She thought of the Confessional…she never came away feeling absolved no matter how great the priest’s strictures had been or how painful the penance.” (August is a Wicked Month)

At times the characters’ religious fervor is so strong that it gives way to a kind of hedonistic self-denial. Yet the novels do not condemn Catholicism. In fact, in Girl and a number of O’Brien’s other books, it is a nun or priest who comes to the protagonist’s rescue and provides safe harbor from the violence of men.

Readers of O’Brien’s fiction appreciate her dexterity with a number of different writing styles and narrative points of view. With each successive novel it is as though she has challenged herself to find a new way to tell a story. While some novels, like Girl and Wild Decembers, are presented in straight-forward style, others such as House of Splendid Isolation, A Pagan Place, and Night are saturated in a murky, Faulknerian fug that dissembles the narratives. At the sentence level O’Brien is a splendid wordsmith who appears to have no use for a thesaurus. At times she boldly repeats the same word or its derivations within a single sentence as if to make the point that the chosen word not only is the best one for her purposes, but the only possible one.

O’Brien’s novels are psychological portraits of women, each fighting to distance herself from her origins in pursuit of an identity that defies the expectations of her birthright. The journey proves to be a troubled, isolating one that cannot but end in failure. Because the past will not abide being disinherited; it demands to be acknowledged and assimilated. And as O’Brien’s mothers and daughters painfully discover, the past always prevails.

· Previous entries in this series ·