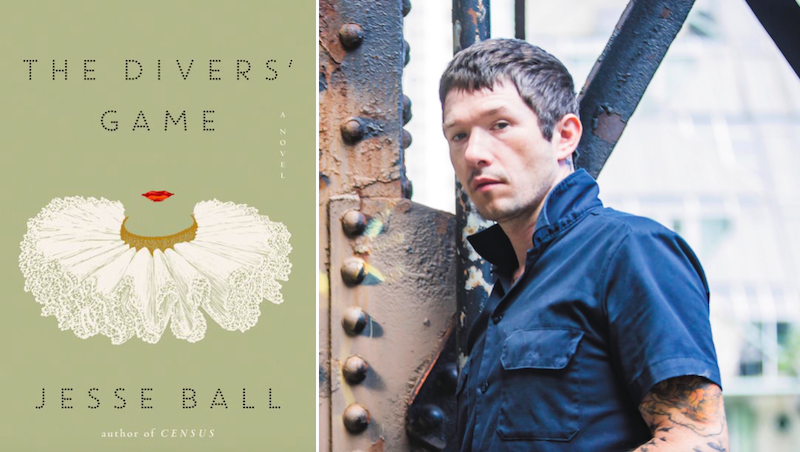

Jesse Ball’s The Divers’ Game is published today. He shares five texts he has personally observed change a student forever upon first reading.

“The Copper Look” from The Man in the Black Coat by Daniil Kharms

He doesn’t think language is what the rest of us think it is. To him it is a very questionable footbridge out over a gaping ravine.

Jane Ciabattari: In this story by the absurdist Russian writer Kharms, Klopov defines “the copper look” to the lady with the yellow gloves like this, the first time: “When a delicate porcelain cup is falling from a cupboard and flying downwards, at that moment, when it is still flying through the air, you already know that it will touch the floor and break into pieces. And I know when a person has looked at another person with a copper look, sooner or later inescapably he will kill him.” Klopov’s second definition flips the picture. What does that teach about inventiveness?

Jesse Ball: The lesson is that everything in a text is held aloft by its constant continuous fabrication. Nothing “is”—not really. If there is a point of reckoning that point is whether the reader’s expectations are both upended and also (in some sense) fulfilled. That the world is constantly in question is a very old philosophical idea. The laughable thing is that writers continue to pretend we can speak about reality as if there were just one. Kharms’ texts demonstrate the idiocy of that notion.

The Notebook by Agota Kristof

She is as harsh as the wheel of a bus, and as timely.

JC: The Notebook, the first of Ágota Kristóf’s trilogy, is the story of twin boys sent to live with their grandmother during wartime, and how they are warped into coldly committing acts considered criminal or evil. Yet they also provide for a deserter in the woods who is starving.

“When we come back with the food and blanket, he says: ‘You’re very kind.’ We say: ‘We weren’t trying to be kind. We’ve brought you these things because you absolutely need them. That’s all.’”

Timely indeed, in today’s time of conflict and torture. Can you imagine actions like theirs dictated by AI (artificial intelligence) at some point in the future?

JB: I imagine the very funny thing about AI will be that in the future you will be able to pay for the level of AI you can afford. Therefore wealthy people will have skycars with powerful AI (equipped with control privileges) that nimbly scoots and dodges them through the crowds and clouds, while lower ranking people will have their cheap-brained AI oxcarts navigating them into traffic jams, relegating them to backstreets. Let’s say that you are trying to drive to buy medicine at a store, but a wealthy person who sets out after you wants the same medicine. Your car might just grind to a halt until they pass you. As for the pair in Kristof’s book, I think they reject the ethical system in which “kindness” exists (along with far more common cruelty, brutality, etc.). As that is the ethical system that has led humankind to drive so many species extinct, perhaps we should question it as well…

“Flower Days” from Selected Stories by Robert Walser

A flood of consequence and joy, and the sense that this impetuous sentiment can be both a fabric and the rules for a fabric…

JC: Susan Sontag called the Swiss writer Walser “a Paul Klee in prose” and “the missing link between Kleist and Kafka.” The narrator of “Flower Days” describes his marking of “Cornflower Day”: “Clad in blue from head to foot, I seemed to myself most graceful, but what is more I felt myself to be most vividly to be a respectable member of the upper classes. Oh, this sweet feeling, how happy it makes me…” What does the story reveal about how a writer creates something akin to Walser’s sense of his society?

JB: This is a bit like what Kharms was doing. Walser also finds it ridiculous and amazing that one can declare a sentiment in prose and then ride that sentiment around like a horse for all to see. The irony is delicious. One can write, “And there was the Queen of England, standing naked in the street, and no one could recognize her, no matter how she said the things she knew to say…” Of course, I cannot compel the Queen to disrobe in the street, but declare it in language and immediately it is as if it has happened.

In Search of Duende by Federico Garcia Lorca

I have seen people find a kind of vocation in this text. Of course, it is a strange and inconsequential priesthood, like being the pope of all mice. But to some of us it is significant.

JC: Lorca’s notion of the duende, “a sort of corkscrew that gets art into the sensibility of an audience,” descends from the “marvelous artistic truth contained in the primitive Andalusian music known as ‘deep song’” and from charismatic performers able to bypass the intellect to bring pure emotion to an audience.

It’s easy to see how reading Lorca could lead to a mystical practice:

The moon has a halo.

My love has died.

Love and death, questions with no answers.

What was your reaction when you first discovered this text? Do you revisit it?

JR: I do—both in the classroom and at home. Lorca was an openhearted person, a kind of model of feeling. In some ways he was also a literary citizen, perhaps in a way that I am not. It is hard to have the kind of hope he sometimes had for literature.

When I first encountered the duende text I felt like I discovered my leg was wet with blood from a wound I hadn’t noticed. But I also felt an immense company. How lovely it is to feel others have gone down the winding mental paths on which our lives find their sweep and cant.

Dart by Alice Oswald

Both this and Memorial: the real writing you thought no one was doing anymore.

JC: Dart is a book-length poem giving voice to the “mutterings” of a river in Devon from its source to the coast:

“Slip-shape, this is Proteus,

whoever that is, the shepherd of the seals,

driving my many selves from cave to cave…

Memorial, which eulogizes the 200 soldiers who died in The Iliad, reframes the classic “as you might lift the roof off a church in order to remember what you are worshipping” and evokes the “bright, unbearable reality” of each death. What makes this work “real writing?”

JR: Because, unlike most of the books published as literature in English, Oswald doesn’t pander. She does not find it her business to congratulate the reader or help them admire their self obsession and narcissism. Rather she provides deliberate observations carefully and clearly stated, observations weighed and measured in her head and heart, observations that do not incline us to one or another tyranny, but that raise up a partly inhuman vision. That’s what real work does: it shows the falseness of the entire human endeavor while also sounding the deep notes of its beguiling call.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.