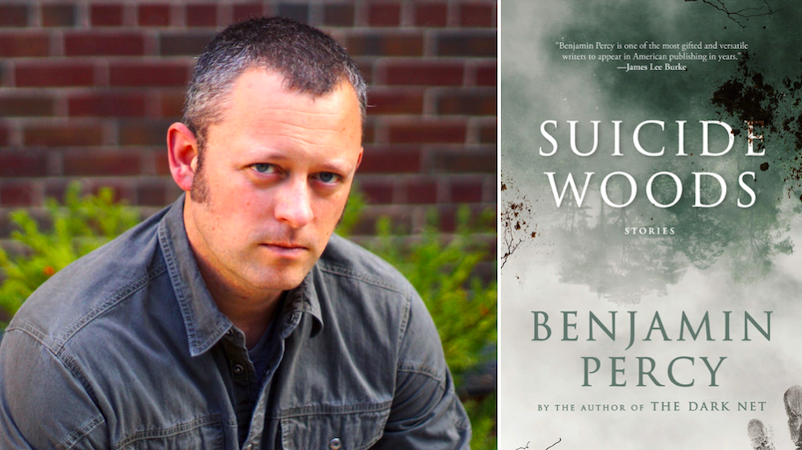

Benjamin Percy’s Suicide Woods is published this month. He shares five tales of suspense and horror that influence his work.

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Like so many others, I kneel at the altar—built from grave flesh and lightning—that Shelley built. But I’ve always been especially fascinated by chapters 6-11. In them the creature, stumbling in a panic through the winter woods, comes upon a cabin. He huddles behind the woodpile and convalesces here and discovers that he can spy on the family through a gap in wall. From them he learns human language and customs and even love. He loves them. That’s why—when he attempts to introduce himself and they reject him in terror—he feels such despair and rage. It hurts and haunts my heart. And I used this as a platform for my story, “Heart of a Bear.”

Jane Ciabattari: “The bear did not know he was capable of love,” you write in the opening of this story. And yes, by the end, he has lived within a human shell, discovered a self, shopped, watched television, robbed a store, nurtured a baby. And yet. His animal self, his rage, persist. How did you keep the balance of his evolving “human” emotions and his animal traits? How did you decide his ultimate choice between them? (One of my favorite details: The moment during a snowstorm when a” great horned owl “floated silently through the woods, and the bear followed its vanishing shape.”)

Benjamin Percy: We’ve all been there at one time or another. When we drink too much, snort too much, smoke too much, sleep too little—when we get cut off in traffic or shoved on the basketball court or triggered on Twitter—we are reduced to tooth-and-claw urges. Who is the real you? The one who, most days, puts on the polite veneer? Or the one who, when your defenses are stripped away, goes wild? That’s the question of Jekyll and Hyde, of the Hulk, of the werewolf, of the bear in this very story (I simply flipped the standard formula)—and it’s a question we all wrestle with but prefer to avoid.

“Last Call” by Larissa MacFarquhar

This article in the New Yorker—about the suicide culture in Japan—made a deep impression on me. And I read it around the same time one of our friends was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor, around the same time someone I know died in a car wreck, around the same time that the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why came out. So death—both our repulsion to it and the release it can sometimes offer—was very much on my mind when writing the title story of the collection, “Suicide Woods.”

JC: I can see the connection between your opening—“Once a month, we shrug on our backpacks and follow Mr. Engel along the trails stitching the four hundred acres of firs and spruce and cedars in Forest Park that everyone calls Suicide Woods,” where this group finds the bodies of those who have killed themselves—and MacFarquhar’s reporting, especially on Ittetsu Nemoto, a Zen priest who conducts “death workshops for the suicidal” at his temple and, from time to time, “gets a group of suicidal people together to visit popular suicide spots,” like the “Sea of Trees” at the foot of Mt. Fuji. You even include some of the exercises Nemoto uses. I’m intrigued by your choice of the eerily effective “we” point of view. What influenced that choice?

BP: I’ve been wanting to take on a first person plural story for some time. In We the Animals, Torres uses “we” to indicate the unified kinship, the mind-meld of three brothers. In And Then We Came To The End, Ferris uses “we” to channel corporate conformity, the white collar hivemind. In this case, I wanted the “we” to capture not just this therapy group but the anxiety and depression and exhaustion so many of us feel right now.

Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell

Sometimes a stylistic challenge is the reason I begin to tell a story. I love the way Mrs. Bridge employs a non-linear/modular format—instead of a chronological through-line—as its narrative spine. And this book—along with the film 21 Grams—made me want to write a mystery, a crime story that employed the same structure. The result of this is both “Suspect Zero” and “Dial Tone,” which make the audience into a co-author, a kind of detective, because you’re rummaging through the broken pieces and trying to see how they all fit together.

JC: My favorite passage in Mrs. Bridge is the scene where India Bridge and her husband sit eating lunch in the country club as a tornado approaches. He insists she stay by his side, and she always does what he says. So they both stare down the monstrous storm. And then: “The tornado, whether impressed by his intransigence or touched by her devotion, had drawn itself up into the sky and was never seen or heard of again.” Connell builds suspense, then leaves us to consider the consequences of the dynamics between this midcentury Kansas City couple. Subtle! In your stories “Suspect Zero” and “Dial Tone,” you juggle the chronology in the fragments that make up “Suspect Zero” and “Dial Tone,” in each case setting up a puzzle to be deciphered. I’m curious if you can explain how you order these sections? Did you know the story in advance and then break it into chunks based on suspenseful storytelling? Did you try them various ways? Or???

BP: In both cases, I first sketched out a chronological version of the story. Then I highlighted moments of spectacle and horror and wonder. I then mixed these up into modular units and made certain each one of them had a nerve jolt. Sometimes the ligature between them is visual or thematic or emotional. But by rearranging the stories—from a standard form—I immediately unsettled the reader and ratcheted up the mystery and the suspense.

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

One of the standard devices in a horror story is “the terrible place.” Whether that’s Hill House or Camp Crystal Lake or the Meyers home. An awful thing has stained this patch of real estate, and anyone who strays into it better beware. I’m fond of Jackson’s story because—like Stephen King’s The Shining—it filters the horror of the locale through an upset psychological prism. So you’re never sure if it’s the place or the person who’s haunted. Or if together they’re like a key fitting into a lock and turning with a deadly click. That’s the approach I took with “The Uncharted,” a novella that takes place in a section of Alaska that is actually known as “The Bermuda Triangle of the North.” But I split the narrative into multiple troubled perspectives, so we’re experiencing layers and layers of physical terror and psychological unease.

JC: Jackson drew upon real-life experiments by the Victorian era Society for Psychical Research in The Haunting of Hill House. There’s an obvious resemblance between Hill House and the house on the Bennington campus where Jackson lived with her husband, critic Stanley Edgar Hyman. (I first saw it in winter time, while visiting as faculty for Bennington’s Graduate Writing Seminars, and I can vouch for how chilling it is! Have you seen it?) Her character Eleanor describes it eloquently:

This house, which seemed somehow to have formed itself, flying together into its own powerful pattern under the hands of its builders, fitting itself into its own construction of lines and angles, reared its great head back against the sky without concession to humanity. It was a house without kindness, never meant to be lived in, not a fit place for people or for love or for hope. Exorcism cannot alter the countenance of a house; Hill House would stay as it was until it was destroyed.

Your character Michelle, the field director for a Silicon Valley map-making tech firm, seems to parallel Eleanor from Hill House. Your use of multiple perspectives gives us a range of personalities and traumas to source the disorienting “dreamscapes” that occur once her team is stranded in the tree-studded island. Are there “real” stories you consulted when writing about this haunted part of Alaska where such a high proportion of disappearances have occurred? How do the explanations given match up with those you include in your story?

BP: I’ve never been to Bennington, but now I must go to pay my respects to the dark queen.

A few years ago, I did a magazine piece and the hook was this: I’m no luddite, but I’m certainly resistant to tech-immersion, and for one month, I would do my best to live like a cyborg. All of these Silicon Valley companies sent me their gear. I had Google Glass. I had an Apple Watch. I had a FitBit (which informed me that a day of writing burns only 34 calories). I had tablets and streaming units galore. I had a Soundhawk earpiece that allowed me to spy on conversations across a crowded room. I also, as a part of this article, got to travel to California and spend some time behind the curtain at Apple and Google. I spoke to digital security experts. I rode in a driverless car (which is a story of its own). I also tried out the Trekker pack. If you’re not familiar with this, it’s a backpack camera unit outfitted the same as their vans. We all know Google street view (which gives you images from neighborhoods and freeways), but the Trekker packs are worn by people who walk into restaurants and down alleyways and into canyons and coral reefs and and and…Their goal is to ultimately map every inch of the world.

I grew up in the woods. I live in the woods now. And here I am with these strange digital prosthetics latched to my body. I liked to imagine that same jarring juxtaposition, that intersection of civilization and wilderness taken to an extreme.

Google wants to map every inch of the world? I tried to imagine what that would look like in some of the most savage sections of the planet, places that are resistant to being known. Places like Alaska, one of my favorite states. I’ve been wanting to write about a section of it—the “Bermuda Triangle of the North”—for some time, and this seemed the perfect opportunity.

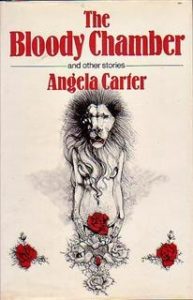

The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories by Angela Carter

Horror is often a place to challenge the heteronormative, and Carter once said, “My work cuts like a steel blade at the base of a man’s penis.” When you stir her fiction up with the queerness of films like Raw and Nightmare on Elm Street 2 and Let the Right One In and novels like The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris and story collections like Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado, you’ve got a smart, defiant, revisionary mix of influences that inform “The Dummy.” I couldn’t think of a better place than the wrestling arena—which tends to be strictly gendered—to upend conventions and blur the lines.

JC: Like Isak Dinesan before her, Carter transmuted fairy tales and folktales in her work—stories drawn from Bluebeard, Beauty and the Beast, Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots. (“I was using the latent content of those traditional stories, and that latent content is violently sexual,’’ she noted in 1985.) Quite a few contemporary writers, including Helen Oyeyemi and Carmen Maria Machado, are also reworking, reframing, remolding traditional tales. Did you have a specific tale in mind when working on “The Dummy?”

BP: Not a fairy tale, but the myth of the golem. Not only because of its raw form—which I thought made for an interesting cousin to someone struggling with gender boundaries—but also because of its disruptive power.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·