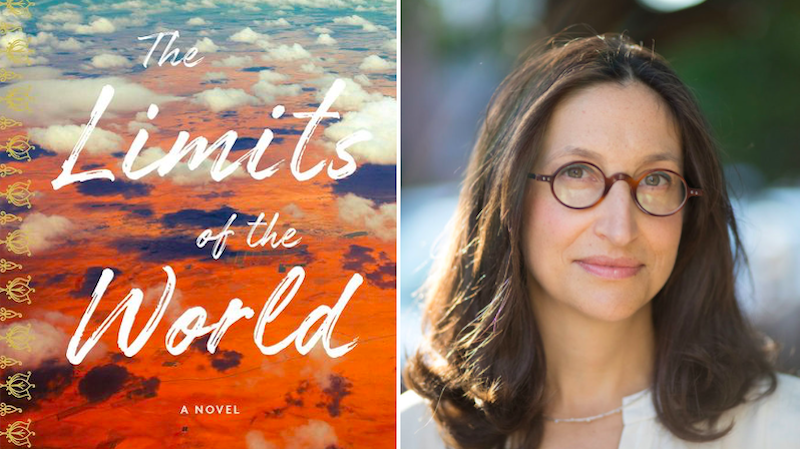

Jennifer Acker’s novel The Limits of the World is published this month. She chose five novels with interracial love to share, noting, “While working on my novel, I began thinking a lot about other novels with interracial relationships. Many novels that profile interracial marriages show those relationships coming undone based on “cultural differences”—clashes based in race and culture, rather than personal characteristics. The books below are all superb, affecting, culturally rich novels that also have the virtue of portraying the individuals in intercultural relationships as idiosyncratic, well-rounded people (and not reduced to cultural ideals/types even in times of stress and breakdown).”

Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteyngart

In general, I’m not a fan of futuristic or apocalyptic novels, but this book won me over with its humor, its big heart, and its exaggeration of contemporary realities to show us just how far gone we already are. I love how (Jewish) Lenny and (Korean) Eunice relate to each other teasingly, underscored by their love for each other, bonding in part over both being the children of immigrants.

Jane Ciabattari: Shteyngart’s satiric chops shine through in his work, including his latest novel, Lake Success, proving that the comic can be as effective as the tragic in stories of love. Do you have a favorite line or passage from Super Sad True Love Story?

Jennifer Acker: Shteyngart is so good about writing about immigrant families, especially first-generation kids straddling different ways of behaving and seeing the world. I love the long scene in which Lenny, child of Russian immigrants, takes his Korean-American girlfriend Eunice to visit his parents on Long Island, and he annotates for the reader all of his parents’ looks and terms of endearment, even the floor: “The floor beneath my feet was clean, immigrant clean, clean enough so that you understood that somebody had done their best.” I also admire Eunice’s sharp tongue, seen in particularly high relief in the futuristic equivalent of IMs with her sister. Her screen name is “Euni-tard,” which cracks me up, and she responds to her sister’s suggestion that it’s easier to date a Korean guy “for the families and everything,” by saying “Yeah, maybe I’ll date a Korean guy like dad. That’s called ‘pattern.’” Eunice has already told us that her father “was a podiatrist who liked to punch his wife and two daughters in the face.” She’s no fool, and she never hides it.

Swing Time by Zadie Smith

I feel like writing in the first person, in the voice of a biracial woman with a white father and Jamaican mother, unlocked a whole new universe for Zadie with this book. There is so much momentum and energy and pathos in the voice, and so much specificity lavished in the girlhood chapters specifically, and also in the West Africa sections. This book has a sprawling feel, entering the world of music, dance, NGO/international aid, in a way that mimics a messy but full life. Identity as a mixed-race girl (here the interracial relationship precedes the current story) is explored with such nuance and tenderness. I found the mother-daughter scenes especially touching. And even though the plot in this book is somewhat strained, the energy of the voice and the memories and experiences made this my favorite of Zadie’s books.

JC: Smith’s use of first-person came up in an interview when Swing Time was a National Book Critics Circle fiction finalist: “I was delighted to be writing in a straight line,” she said. “But soon enough other voices appeared, especially in the West African portions. It’s the ham in me but I like recreating voices. I feel a certain kind of novelist sneers at this as a sort of low, theatrical art—’character making’—akin to playwriting. Maybe it is, but I get a lot of pleasure out of it.” You use first person in alternating sections of The Limits of the World, which give the back story of an Indian family arriving in Africa in the late nineteenth century. What made you decide to use those first-person passages, and what do they accomplish that couldn’t happen in third person?

JA: I always knew I wanted those sections to be from within the Kenyan Indian community, rather than in the third person, which is less intimate. But initially they were first person plural—“We.” I found that it was difficult to keep the momentum of the sections going when written in a collective voice, because the passages weren’t tied to any narrative found in the rest of the book. Putting them in the voice of the grandfather, the patriarch who is losing his memories to dementia, gave urgency to the transmission of this history. And it allowed me to write a particular storyline that impacted particular people, creating sections that built on each other instead of hovering there as pretty but not very functional set pieces.

All Our Names by Dinaw Mengestu

There is an understated quality to the prose and the inner lives of this book, which focuses on a love story between an Ethiopian refugee and his white American social worker; these are individuals who nearly try to erase themselves, and yet seek shape and purpose in the other. They contemplate their obvious differences with natural curiosity, and we see how others are suspicious of them and condescending but the book never relies on superficial differences to tear this couple apart.

JC: Mengestu identifies each of his characters so clearly. Isaac, newly arrived in the U.S.: “When I was born,” he says, “I had 13 names. Each name was from a different generation, beginning with my father and going back from him. I was the first one in our village to have 13 names. Our family was considered blessed to have such a history….I felt as if I had been born into a prison…I went to Addis Ababa, and then took buses to Kenya and Uganda. I was no one when I arrived in Kampala; it was exactly what I wanted.” Helen, the Midwesterner, who cannot “see” Isaac’s past, notes, “My father named me Helen for reasons he said he couldn’t remember.” At what point do you think the two come to really know each other?

JA: This doesn’t happen for a long time. More than halfway through the novel Helen catches Isaac in a lie—she sees him driving when he says he has never learned to handle a car—and she waits a long time outside of his apartment, watching him with someone else inside. When Isaac emerges, they enact a very American scene—cruising down the highway and eventually finding a motel to stay in for the evening—and in the car, at high speed, Isaac begins to sob because he’s just learned the other Isaac (his mentor and comrade) has died. At the motel they are tender with each other, and with this scene begins the period in which they are truly intimate, not just in body but in spirit and mind. These pages are full of wonderful awareness—of each other, of themselves, and of the culture (1970s Midwest) that surrounds them and infiltrates their daily lives.

Breakable You by Brian Morton

Though historic antagonisms between Jews and Arabs are acknowledged, sometimes challengingly, in this novel, “cultural differences” are not the points of weakness. Conflicts stemming from Maud and Samir’s politically opposed ethnic and religious groups are heatedly evoked, especially in the beginning, but they give way as the couple falls in love and discover each other’s scarred and delicate interiors. This book was also important to me because Maud is a student of philosophy, much like one of the protagonists in my novel. It was an excellent lesson in how to weave intellectual ideas into the emotional threads of a novel. Brian Morton is also a beloved teacher of mine, and I love the precision and care of his language.

JC: Can you say more about what you learned from Morton about writing a love story that is also a novel of ideas?

JA: Maud, who is writing a dissertation on Kant, is brainy, and she’s not afraid to show it. She opens a conversation with the man she is trying to date, Samir, with “Seneca wouldn’t approve of me,” and then without much of an invitation, begins to tell him about Seneca, quickly summarizing his impact on philosophy. She goes on to note that the “philosophers closest to her heart were those who wrote about how we can find a way to recognize one another, empathize with one another.” This is in the midst of an awkward dinner in which each character has a hidden history. In order to write an integrated novel of ideas, as Brian does, you need for the intellectual problem to also be a life problem, to have a bearing on the action, and this is what I tried to do in my novel. I try to show how being invested in a philosophical viewpoint affects Sunil’s relationships with people, and the actions that he takes or refuses to take. Sunil and his mother do not share the same beliefs about how to treat people, and this is disastrous for them. Sunil’s wife Amy is on his side, but she balks at some of his hardline approaches, which strains their marriage.

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie

I was working at Knopf when this book was published, and I read first in galley form and was simply blown away. I had not read her previous book and had never heard of Chimamanda before—after reading this novel I simply waited for her to become a rock star. No one who writes this beautifully about war and love and jealousy can possibly remain little-known for long, and I recommended the book to everyone I knew. The interracial relationship in this novel is between Englishman Robert and Nigerian Kainene. (Robert gets in trouble for sleeping with Kainene’s twin sister.) The epic scale of this book impressed me immensely and I loved being immersed in a new-to-me society, and seeing how complicated all the social relations were. It’s the deep interiority and subtlety of emotion set against the backdrop of such disastrous conflict that make this book one of my favorite novels.

JC: Half of a Yellow Sun was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle award in fiction, her later novel Americanah won that award, and Adichie is a powerful presence in global literature today. Which of the personal idiosyncrasies Adichie details so well most affect the relationship between Kainene and Robert?

JA: Kainene is ambitious, business-minded, forthright, and sardonic. Robert is a writer with artsy interests, and he’s often stoppered by shyness and social discomfort. An intensely moving scene follows Robert’s betrayal. (For reasons he can’t quite articulate to himself, he has slept with Kainene’s twin sister.) I expected a big, fierce fight in keeping with the scale of Kainene’s hurt, but instead she takes drastic action offstage. She burns the manuscript Robert has been working on with “unbridled energy” over the past many months. This retaliation somehow zeroes out her pain, and Robert realizes that she would not have bothered to hurt him if she was going to leave him. The section ends with his reflection that perhaps he is not a true writer after all, because true writers would protect their art above all, and he is choosing love. It was such a smart authorial choice, leaving each character wounded, but together.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·