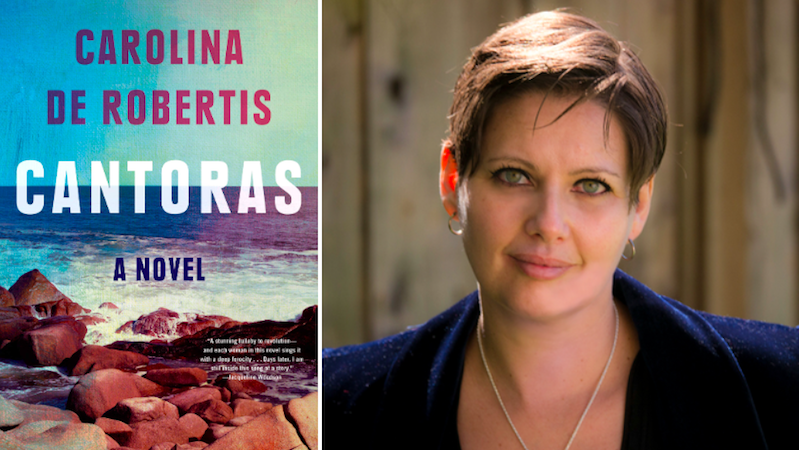

Carolina De Robertis’ Cantoras is published today. She shares five great novels of revolution.

Another Country by James Baldwin

In this astounding, keenly lyrical novel, Baldwin probes the intimate, erotic, racial, and spiritual dynamics of social change. His characters are so achingly real and raucous in their humanity, it’s difficult to believe they aren’t alive, breathing around us—perhaps because, in some deep way, they are. It’s stunning that, in the early 60s, Baldwin had the vision to give voice to what we now call intersectional realities, and the revolutionary change necessary for the U.S. to live up to its ideals of equality for all. The book was so darn prophetic that it’s still ahead of our times.

Jane Ciabattari: Indeed it is. Baldwin wrote so frankly about what America is, with all those intersectional realities, and yet, do you think he also holds out the possibility of what we could be, if we lived up to the promise of equality?

Carolina De Robertis: Absolutely. Every single one of Baldwin’s six novels carries the possibility of a better, more just society embedded in its pages as a kind of hunger. He paints for us the complexity and intimate depth of the problems, and also the possible paths forward. Another Country aches with tenderness and desire, and interracial erotic relationships become a site for discovering the limits and potential of transformation. This is, I think, a fundamentally queer vision of social change. Love and desire become forces with the power to shatter walls, and shake the fortress. Are the limits stronger than the longings? Can love surmount oppression? Perhaps. Perhaps not. He leaves the questions open, all the hunger laid bare. There’s no airbrushing here, no false safety. Everything is raw, and gleaming. Between the lines of this novel lies a secret handbook for the cultural revolution we’re still part of today.

Texaco by Patrick Chamoiseau

Sweeping, dazzling, and volcanically poetic, this Francophone novel traces the history of Martinique through the eyes of an old woman in a slum who, to save her people, recounts the story of their trajectory from brutal enslavement to political turmoil to their claiming of an abandoned Texaco plant. The scope of Hugo’s Les Misérables and the ferociously imagined richness of One Hundred Years of Solitude meet in a visionary, gigantic, Black-centered narrative that subverts the paradigms of institutional power.

JC: What’s fascinating about Texaco, which won the Prix Goncourt when it was published in 1992, is Chamoiseau’s stitching together of so many stories through the narration of Marie-Sophie Laborieux, who tells the history of the endangered community named Texaco back to her ancestor Esternome, a former slave. The hybridity of the novel’s shape and language is striking. How does Chamoiseau do that!?

CDeR: That’s a good question. At this point in my life, I’m unable to read the original French (though I dream of arriving at that level of skill one day!), but it would be incredible to directly experience the hybridity of his formal French with the Creole of his nation and the African linguistic inflections of the people he portrays. Fortunately, his English-language translators did an excellent job of rendering these nuances, which is something I’m particularly passionate about as a literary translator myself. So Chamoiseau’s innovations and subversions are on the macro level, in terms of the stories he tells and the centuries he sweeps through, and also on what translator Emily Wilson calls “the microscopic level of the word.”

And this is just a guess, but I think he also achieved what he did by having fun. His characters are as exuberant as his sentences, his humor is as lavish as his syntax, even in the thick of atrocity. As a writer, I relish that.

Guapa by Saleem Haddad

This passionate, elegant, deeply engrossing novel takes us into a day in the life of Rasa, a young gay man in an unnamed Arab country, as he grapples with political and personal upheaval, as the streets of his city fill with uprising, his queer friends confront the authorities, and his grandmother catches him naked with another man. The dangers and possibilities of social change are explored in intimate, exquisite detail, made to breathe and sing.

JC: Haddad is so fluid in his shifts from one scene to the next, his awareness that the “eib” or shame Rasa feels under his grandmother’s gaze is also central to a surveillance state, where no one is free. Guapa, which means “pocket of hope,” is the name of an underground nightclub where Rasa’s friend Maj performs. Now Maj has been arrested, and Rasa’s own freedom may be in danger. Which of the scenes from the past, including Rasa’s time in the U.S. after 9/11, strike you as most revealing of Rasa’s choices?

CDeR: I’m not sure that I can pick just one scene, as they’re all imbued with crucial pieces of Rasa’s journey, and the larger journey of social and political liberation that’s refracted through his story. Haddad’s prose is truly gorgeous, and flows bravely into the depths of his protagonist’s consciousness, even when he’s surrounded by dramatic action.

All the scenes that portray the stirrings of an Arab Spring uprising are profoundly powerful. So is the scene where Rasa lies down in a bathtub with the lights out and recalls his time in the United States as a young Arab immigrant, post-9/11. All those rich recollections take place, and then, many pages later, we return to Rasa in the bathtub in the dark, so it’s all technically one scene. And what a place in which to turn the queer Arab gaze on U.S. culture. It’s almost like a baptism, only instead of water he’s immersed in darkness. It’s so exciting and inspiring to read contemporary international work like this—it stretches the world open, for me and for so many others.

Notes of a Crocodile by Qiu Miaojin

This novel has been an underground queer classic in Taiwan since the early 90’s, but only appeared in English for the first time in 2017. Qiu was herself a renegade who tragically killed herself in her mid-20s; in this luminous book, her vision of lesbian desire and gender-bending transgressions in post-martial-law Taipei is so raw and viscerally rendered that you feel on every page the vast courage of coming out, and the earthquake it implies for the status quo.

JC: Qiu’s energy in response to the possibility of the freedom to be herself, as Taipei is being transformed into a more liberal city after the end of Chinese martial rule, is contagious. As she writes at the beginning of Notebook 1 of her narrator Lazi’s journal, “In the past I believed that every man had his own innate prototype of a woman, and that he would fall in love with the woman who most resembled his type. Although I’m a woman, I have a female prototype too.” She struggles with shame, with seeing her love for women a “monstrous sin,” yet as a college student she creates a community of friends who accept her choices. How do you think the surreal crocodiles work to symbolize the choices she faces?

CDeR: That’s one of the mind-blowingly brilliant elements of this book—the story of the crocodiles. It alternates with the narrator’s story, appearing intermittently as a parable, or surreal thread, or extended metaphor, and I can’t speak for all queer readers but for me it was the most incredible revelation to read. The crocodiles are mistrusted, maligned, denounced; they are forced to live in hiding; they are fetishized and exoticized by a popular culture that wants to put them in the limelight without seeing them on their own terms. Meanwhile, these crocodiles hunger only to drink their tea and be alive. The humor and absurdity weaves inextricably through the pain.

Qiu was utterly prophetic in imagining a time when LGBTQ+ lives and truths would get their Will and Grace and Queer Eye moments, to use a shorthand, becoming prurient window dressing for heterocentric culture, and yet still struggle for voice and safety. And, for queer readers, she wrote our beauty—the beauty of our hungers, their goodness and power, the joy and risk and cost of being ourselves—in the most inimitable way.

Qiu means so much to me, as a lesbian writer, and as a queer Latin American writer. Honestly, I have no words.

Women Talking by Miriam Toews

All revolutions should include a plan for dismantling the patriarchy—and for that, this novel is required reading. A group of Mennonite women, systematically sexually abused by men in their community, gather in a hayloft to discuss whether to leave, or stay and fight. Their conversations are particular to their circumstances, yet as timeless and timely as Shakespeare, not to mention exquisitely wrought and subversive as all get out. A work of genius.

JC: And yet the reader realizes the narrator of Women Talking is a man, because the women have been forbidden to read or write. How do you think that affects the story?

CDeR: I think this is a beautiful and brilliant framework for the novel, for various reasons. First, it means that our narrator, through whom we witness the conversations, is the only person in the room who has not been repeatedly raped. This creates a bit of space, a buffer, between the reader and the horrors at the heart of this book. We avoid plunging into the interiority of trauma, and stay tethered to the dramatic tension of the now.

Second, the man as deep witness to these women’s conversations offers the book a narrative arc wherein the male listener moves ever deeper into understanding what it might be like to live in the women’s skin. Implied in that structure is the possibility that we, the reader, might also journey across this arc toward revelation, about the nature of sexual violence, and what it means to get free.

Third: the man is in the room to take notes. Not to speak, but to listen. As the title informs us, it is the women who are talking. Women. Talking. Men. Listening. Now there’s a revolution, indeed.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·