Susan Shreve’s novel More News Tomorrow is published this month. She shares five books about violence.

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye, published in 1970, is the story of Pecola Breedlove, an eleven-year-old black girl who lives in Lorain, Ohio. Pecola believes her life would be better if she met the standards of white beauty and had blue eyes. Her story is told from multiple points of view in a novel about sexual violence, blackness, and love. At home she is unloved by her mother, Pauline, raped by Cholly, her father, and is befriended by Claudia MacTeer who is from a loving, united family and who rebels against black women’s idealization of whiteness. Morrison believes in the power of story to redeem. She loves/forgives Cholly and Pauline in spite of their cruelty and violence, understanding the context of their damaged lives.

Jane Ciabattari: How does Morrison use language to convey her empathy for Cholly and Pauline as well as Pecola?

Susan Shreve: Morrison’s language is rich and poetic, warm, emotionally charged, operatic. She is a storyteller who loves and understands her characters, whatever violence they have perpetrated. Through the rhythm and crescendos of her language, we understand Cholly and Pauline in the context of the difficult lives they have lived and in spite of their cruelty and aggression.

American Pastoral by Philip Roth

American Pastoral, the first of Roth’s American trilogy, is the story of Seymour Levov, “the Swede,” whose charmed life as a great high school athlete and successful businessman with optimistic belief in self-reliance and hard work, in the values of virtue and dignity, is crushed by the political violence of the sixties. His daughter Merry, largely responsible for her father’s shattered life, is responsible for setting off a bomb that kills a man. The story is told through the voice of Nathan Zuckerman, Roth’s alter ego, who idolized “the Swede” as a high school athlete and American success story. Merry is a character of complexity reflective of the sixties as well as of our present political crisis.

JC: How does Roth prepare us for Merry’s act of violence and its effect on “the Swede”?

SS: Seymour Levov ‘the Swede,’ is a near perfect expression of postwar American idealism. A great athlete, a man of decency, honor and emotional self-containment, he has a moment of vulnerability when his daughter is eleven years old. Overcome by sudden emotion, he loses control of his standards of decorum and passionately kisses her. Later as a teenager when Merry becomes an activist in the sixties revolution against the war in Vietnam, she sets off a bomb at a small post office, killing a doctor beloved by the community. “The Swede” is ultimately destroyed by his own sense of responsibility for Merry’s acts of violence, which he believes a result of his own moral transgression. He sees what he did when his daughter was young as a betrayal not only of Merry but of himself.

Black Water by Joyce Carol Oates

The taut story of the novella Black Water is familiar as Chappaquiddick—the small island where Senator Teddy Kennedy’s car went off the road into the water; he survived and the woman with him drowned. Oates imagines what might have happened to Kelly Kelleher in the short time between the accident—in which, inebriated, The Senator goes off the road and the car overturns in the water—and her death. The book is simple, elegiac, and intense, calling into question the relationship between carelessness, a fundamental disregard of human life, responsibility—and violence.

JC: Is there a particular scene that, for you, crystallizes the sense of carelessness Oates portrays?

SS: Oates writes often about victims of violence, particularly against women. She has an uncanny ability to capture the precise gesture that is both chilling and unforgettable. As The Senator tries to get out of the car into the open water in an effort to save his own life, he steps on Kelly Kelleher and pushes off her body to escape. Whatever else happened that night, this nightmare detail remains with the reader as true to fact and to fiction.

The Round House by Louise Erdrich

Joe, the narrator of The Round House, is the son of a judge on an Ojibwe reservation in North Dakota. The book opens with father and son, then thirteen, working together on their house. Soon thereafter they learn that Joe’s mother Geraldine has been brutally raped near a ceremonial structure called The Round House. Too young to understand the act of rape and its consequences, the young Joe spends the better part of the book with his friends, canvassing the reservation, learning its culture and limitations, dealing with his own sexuality and the brutality of his mother’s assault. The ambiguities of justice and the law are made clear as Joe, in his search for justice for his mother, discovers that the suspect, a white man, is not punishable by Native law. The young Joe balances his father’s belief in the rule of law against his grandfather Mooshum’s conviction that in accordance with the elders, a monstrous figure like the rapist should be killed.

JC: I’m wondering if Erdrich’s exquisite description of the landscape in this novel had any influence on your own details of the setting of More News Tomorrow—as your characters travel up the Bone River to Missing Lake, Wisconsin.

SS: I have written about cities primarily, Washington and New York, places I’ve lived and know. Things happen in cities and there’s much for the novelist to depend on. But in More News Tomorrow, I am writing about a canoe trip on a river in northern Wisconsin in which most of the action is going to occur within the confines of a river and a camping site. It was a hard task to create the tension necessary for a story with qualities of a thriller. Certainly the territory of northern Wisconsin is similar to the landscape of The Round House. And yes, Erdrich’s rich descriptions in many of her novels were an influence. My characters are strangers to this river setting—city people with little experience in the wilderness. Setting itself becomes a character in this book–beautiful, dangerous, unpredictable.

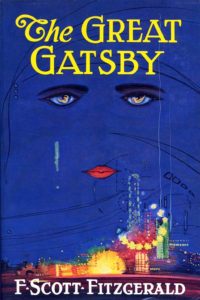

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Great Gatsby is a story, maybe the story, of the disintegration of the American Dream, the elusiveness of the past and the irony of a contradictory democracy. It takes place on Long Island in the summer of 1922, a time of postwar cynicism and greed not unlike our own. Jay Gatsby, a mysterious multi-millionaire—about whom we know little until the end—has bought a mansion in West Egg on Long Island hoping his extraordinary parties will attract his former beloved, Daisy Buchanan, a wealthy debutante married to Tom who lives across the bay. Nick Carraway, the Midwesterner and bonds salesman who narrates the novel, rents a small house next door to Gatsby. Nick knows Daisy and Tom and when he learns of Gatsby’s longing for Daisy, he arranges a tea and invites her without letting her know that Gatsby will be there. The couple rekindle their romance. The reader, confident of Nick’s honesty and sensing incipient danger in the developing story of lust and adultery, money and carelessness, recognizes that things will not end well, that feelings of betrayal run high and violence is inevitable.

JC: How does Gatsby’s mysterious past influence the plot, leading to inevitable violence?

SS: The plot is driven by what we don’t know but suspect about Gatsby—that his money comes from criminal engagement, that he may have killed a man and the reader is unsurprised to learn he was James Gatz who came from nothing, inventing himself in his own image of the American Dream. This novel cannot end well.

Then there’s the irony of Gatsby’s death, which is a result of his taking the responsibility for driving the car that ran over Myrtle, Tom’s lover, when in fact it was Daisy at the wheel. Which leads to his own death in the swimming pool at the hand Myrtle’s husband.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.