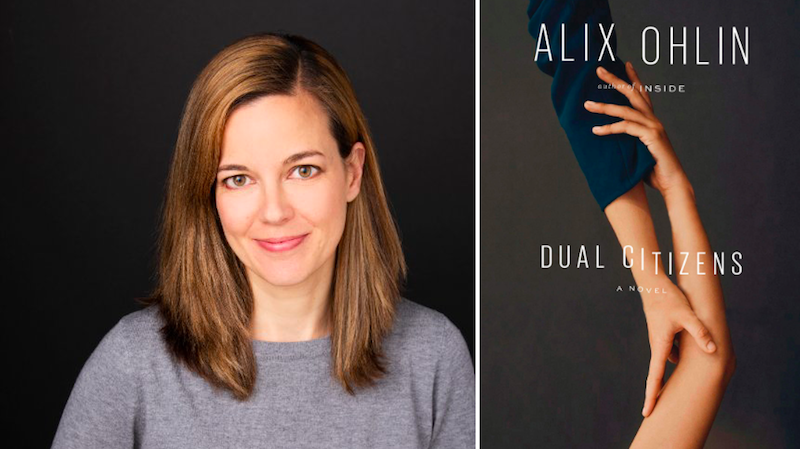

Alix Ohlin’s Dual Citizens is published this month. She shares five novels about sisters.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson.

“My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance,” opens Jackson’s classic of deadpan horror. “Everyone else in my family is dead.” Sure, Mary Katherine, also known as Merricat, is a murderer, but it’s her sister Constance’s radically determined domesticity—she keeps on cleaning and gardening and making tea as the violence mounts—that is truly seditious. Unshakeably weird, forever united, the Blackwood sisters preserve their home on no one’s terms but their own.

Jane Ciabattari: I’ll never forget spending time on the faculty at Bennington’s low-residency MFA program and visiting the house where Jackson and her husband, Stanley Hyman, lived for the first time. She uses this landscape so well in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which, like Jackson’s story “The Lottery,” capture the sense of prosaic evil in a village, in a family on the “outside,” and in these two sisters, ten years apart, one a murderess, the other who seems as agoraphobic as Jackson seemed to be. How do you think Jackson accomplishes Merricat’s wicked yet playful narrative voice?

Alix Ohlin: I’m so jealous that you got to see Jackson’s house—I’d love to go there. You’re right that the landscape of the New England village and the house just outside it is used so effectively in We Have Always Lived in the Castle. You couldn’t get to the darkness in her work without the domesticity, the weird coziness that lives in its midst. To me Merricat’s voice is the scaffolding on which the entire novel is built—all the energy of the story flows from it. It’s a great use of the intimacy of the first person, which plunges you into the subjectivity of the narrator’s voice and before you know it you’re on her side, no matter what you find out about her. Merricat is so charming, so deadpan, and loving in her own way—so much an object of her sister’s love, too. She’s genuinely child-like, so there’s a purity to her wickedness, if that makes sense; it doesn’t feel calculated or mechanical. I find I want to protect her and Constance, want them to remain safely walled away in that house forever.

Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen

The Dashwood sisters, Elinor, Marianne, and Margaret, must fend for themselves when their father dies. As always with Austen, there are suitors, subplots, and socio-economic anxiety, but what stays with me from this novel is the particular caring between Elinor and Marianne. When Marianne is jilted by the feckless John Willoughby, and when she later becomes ill after walking in a terrible rainstorm, it’s her vulnerability that brings out the steel in Elinor.

JC: Marianne weeps when Willoughby goes away to London, and as you note, is troubled and ill for days after. But Elinor has a different reaction when Edward leaves. Do you find her steeliness equally convincing?

AO: Austen’s heroines are usually a combination of spine and vulnerability, aren’t they? They recognize the precarity of the position they’re in and are clear-eyed about it. Elinor is reserved and practical and suppresses her emotions but she’s of course broken-hearted when she learns that Edward is engaged to Lucy. So she understands full well how upset Marianne is even though she herself would never react in that fashion. I think Sense and Sensibility even more than Pride and Prejudice is built on this relational character portrait of sisters with wildly differing, complementary personalities. Marianne is melodramatic and gullible and expressive, and Elinor is none of those things, and yet their lives are full of parallels and overlapping experiences.

Sister Mine by Nalo Hopkinson

Conjoined twins Makeda and Abby are the daughters of a celestial demigod and a human woman. When they’re separated to save their lives, only Abby maintains her magical ability. The two sisters go their own ways, reuniting when their father, the demigod, goes missing. A family story in a fabulist universe, this novel by the award-winning Caribbean-Canadian Hopkinson plays joyously with language and myth.

JC: And one character, Lars, is Jimi Hendrix’s guitar. The sibling rivalry between these two is complicated by the consequences of their separation—Makeda loses her godlike qualities, Abby loses a leg. I found the back and forth between love and sourness, the squabbles, the hang-ups, quite realistic, despite the fabulist narrative. Did you?

AO: Without a doubt. It’s truly a family story and so much about the friction between sisters. Reading the book I get so immersed in that dynamic, and at the same time there’s this play with language and concept that Hopkinson does that’s so inventive. It creates such a bright texture, this combination of the familiar and the unexpected, like a kaleidoscope where you recognize the colors but each new page shows you patterns and arrangements that surprise you.

All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews

Yoli’s sister Elf is a brilliant and successful classical pianist who attempts suicide; throughout the novel, Yoli tries to hold on to her and keep her among the living. It is astonishing to me how Toews can take this dark material and make it funny, how she wrote a book about death that is rich in comfort. Much of the dynamism comes from Yoli’s voice, which is wisecracking and honest and dismissive of all cheap sentiment.

JC: One of my favourite scenes is Yoli’s memory of “the moment Elf took control of her life.” Despite the restrictions against music in their strict Mennonite community, the piano came into Elf’s life as a “creative outlet” for her energies, recommended by a doctor to prevent her from becoming wild. “Wild was the worst thing you could become in a community rigged for compliance,” Toews writes. Elf is fifteen, the bishop and his “posse of elders” drop by for a visit, and from a spare bedroom Elf plays her favorite Rachmaninoff prelude. “It was her debut as an adult woman and ….as a world-class pianist. I like to think that in that moment it became clear to the men in the living room that she wouldn’t be able to stay, not after the expression of so much passion and tumult, and furthermore that to hold her there she would be have to be burned at the stake or buried alive. It was the moment Elf left us.” These backward glances bring such richness to Yoli’s ongoing struggle to keep Elf alive, don’t you think?

AO: I like that you picked out that scene, because some of those same ideas around wildness and compliance, I’m realizing, are in my book which also features a sister who plays the piano and who is savagely independent. Elf absolutely and categorically rejects the terms of engagement, and that moment when she’s fifteen is the fulcrum of her escape. There are some similarities to the sisters in Dual Citizens who find their desires to make art (to play the piano, to make films) complicated or compromised by male authority figures. Toews is amazing at interleaving the past and present to show how enduring the love between Elf and Yoli is. The backward glances, as you call them, don’t weigh the book down but rather testify to how Elf lives with Yoli every minute—she’s inside her, and always will be. For people who grow up together the past is continuous with the present; you’re looking at your sister as an adult but she’s also the teenager you remember and the child you remember and the part of yourself you remember, too. I think fiction (especially in the hands of a writer as masterful as Toews) is so well-situated to capture that multi-faceted experience of memory, the manifold consciousness of time.

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson

Housekeeping’s Ruthie and her sister Lucille are raised in Fingerbone, Idaho, by a series of relatives, the last and weirdest of whom is their aunt, Sylvie. The final paragraph of this novel is one of my favorites in literature, and one of the saddest, as Ruthie, who has left town with Sylvie, imagines Lucille in a restaurant: “No one watching this woman…could know how her thoughts are thronged by our absence.” Life is loss; love is inseparable from abandonment; and sisters, though they may part forever, never forget what they left behind.

JC: An elegiac ending. And as Robinson writes, “Families will not be broken. Curse and expel them, send their children wandering, drown them in floods and fires, and old women will make songs of all these sorrows and sit on the porch and sing them on mild evenings.” How did these sisters, so different in temperament, influence the sisters in Dual Citizens?

AO: Housekeeping is a world of women, of unconventional families, and of women as outsiders—these are all themes I drew on in my book. Ruth and Lucille have radically divergent reactions to being outsiders. Ruthie is drawn into outsider life, through her connection to for Sylvie, in this almost mystical, fatalistic way. Lucille fights against it; she wants to stay in town and be part of the regular community. It’s so heartbreaking to me when their fundamental personalities and needs drive them apart, like a tragic love story. And that line you quote about the old women making songs of all these sorrows—what is that about if not women making art out of heartbreak? I thought of Dual Citizens as a love story between sisters, a testimony to the intensity of their relationship, and the art they make is fundamentally connected to that bond. Housekeeping is a book about the sacred, I think, which mine is not, but I’m deeply inspired by the beauty of Robinson’s language, which itself feels so enduring while her characters confront the transience and impermanence of life.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·