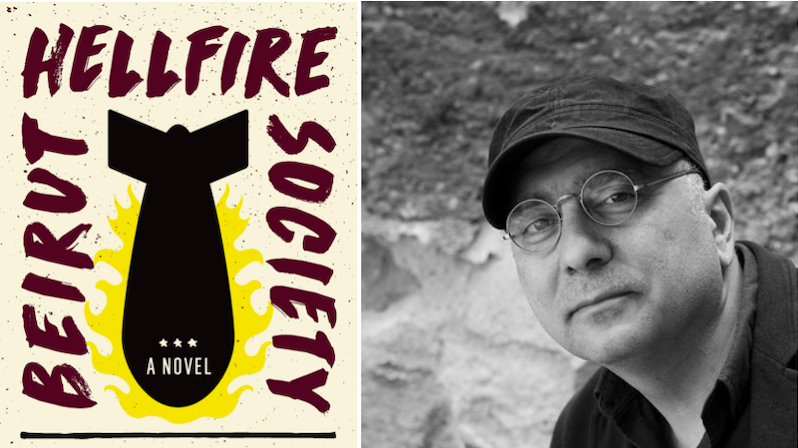

Rawi Hage’s Beirut Hellfire Society is published this month. He shares five books about Beirut.

Dear Mr. Kawabata by Rachid Al-Daif

The novel takes place during the early period of the Lebanese war. A philosophical letter addressed to the Japanese Nobel Laureate Yasunari Kawabata.

Jane Ciabattari: Rachid, the narrator, lies in Beirut dying of wounds from the civil war, addressing his narrative to Kawabata, who committed suicide in 1972, at age 73. “Before I continue to pour out my soul,” Al Daif writes, “let me confide in you that Lebanon is one of those countries that produces nothing but its own periodic tragedies.” Why would Al-Daif select Kawabata as a focus? Is it because Kawabata also wrote of the ongoing conflict between tradition and modern ways?

Rawi Hage: I believe Al-Daif chose to write to a person distant from the regional and local conflict. In the Lebanese Arab context, Yasunari Kawabata is culturally neutral. He’s not a Westerner, hence the narrator is not associating himself with colonial history. But Kawabata is not an Arab either, so it might be a way to avoid an internal dialogue.

Kawabata committed suicide, he didn’t die as a warrior or a martyr as many young men aspired to during the Lebanese war. His death was private and not ideological. I believe Al-Daif also chose him because of distance. He was far away and neutral, and this might be an incentive for the Japanese writer to listen.

The novel is also about self-annihilation or suicide. I believe all wars are an act of self-destruction and ultimately a battle against the self.

La Tanbout Al-Jouzour Fee Al-Sama’ by Youssef Habchi Al-Achkar

Obscure and never translated from Arabic, Al-Achkar is arguably the first existentialist writer of the Arab world. Considered one of the most significant and undervalued writers by many Lebanese and Arab writers, including the Egyptian Nobel Laureate, Naguib Mahfouz.

JC: Can you tell those of us who aren’t able to read Al-Achkar in Arabic how Beirut is depicted in this novel?

RH: The depiction is more of a particular generation in the last period of the golden age of Beirut, the early 1970s. Lost, existentialist lives that alternated between aspirations to a bohemian life and to newly acquired western modernity.

Beirut was depicted as it was at the time, as an open city and a space of transition and refuge for many of the intellectual in the Arab world at the time. The city was seen in many lights, as a space of experimentation, thought and liberty. But within theses space of liberty there was a sense of loss.

The Kingdom of this Earth by Hoda Barakat

A historical novel highlighting the disappearance of the Christian Communities from the Middle East.

JC: Barakat was longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction with this novel, and won that prize in 2019, for The Night Mail. The Kingdom of this Earth portrays an isolated rural Christian community in north Lebanon from the 1920s to the beginning of the Lebanese civil war in the 1970s. How are they are able to sustain their traditions through this period? And how do their lives change?

RH: It’s a peculiar epic of a sub-community in the Middle East whose history is complex and undoubtedly tragic. It’s the fate of many minorities in various empires. Barakat’s novel highlights the geographical isolation of this community, a mountainous people whose only defence against total assimilation into the Islamic majority is the geographical terrain. That bit is not specific to the Christian community alone. Lebanon’s constituencies are of a collection of religious minorities, including Muslims minority communities, who take refuge the high terrains of the region. pThe novel is ultimately about extinction. And I must say that Barakat is not the only writer who talks about this subject. Many other Lebanese writers from that background in the last decade wrote, independently, about the disappearance of Christianity from the region. Elias Khoury, Charif Majdalani, Rachid El-Daif, and myself included, in my last novel, all somehow produced work about the notion of extinction. The subject is not always as overt as in Barakat’s novel, but the lament mixed with acceptance are noticeable.

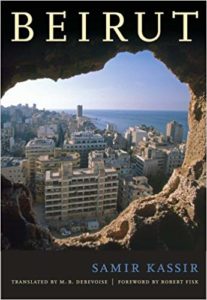

Beirut by Samir Kassir

A history of the birth and the rebirths of Beirut from pre-Roman period to contemporary time.

JC: In his comprehensive and definitive history of 4,000 years, Kassir notes that in 1974, Beirut “ranked among the greatest metropolises of the Near East”—this is before the “chain reaction of violence that between the fall of 1975 and 1990 came close to sweeping away the city, and with it the country itself.” Does any particular period in this history speak to you? His writing of the Civil War?

RH: I lived through nine years of the civil war. But what’s remarkable about the book is how it charts the progression and metamorphosis this ancient city underwent since antiquity. Beirut had periods of total abandonment and then revival. Samir shows that ultimately Beirut was always a city of migrants and refugees. Its latest rebirth was in the eighteenth century, as a joint venture between the Ottomans and the French, and this rare collaborative endeavor between the east and west is one of Beirut’s characteristics.

I think Lebanese literature is also unique in that sense. Cultural fusion is an essential part of its literary tradition, which eventually had a significant impact on the novel in the Arab world. Samir Kassir was assassinated on the June 2, 2005 in Achrafieh, Beirut.

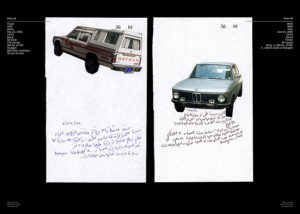

The Atlas Group by Walid Raad

Performances, video, and photographs. A fictitious archive consisting of lectures, documentaries, and installations about the civil war in Lebanon.

JC: Raad’s fifteen-year documentation of the Lebanese Civil War has been shown exhibited internationally, including in Berlin and the Guggenheim in New York. It includes a set of photographs, films and notebooks by a fictitious Lebanese historian, Dr. Fadl Fakhouri. One film that captures moments when it seemed the civil war was over, and another feaures advertisements for surgeons, psychiatrists, and orthopedic surgeons, all urgently needed in wartime. How did the visual images in The Atlas Group influence your work on Beirut Hellfire Society? Or your character The Bohemian, the photographer who exchanges his camera for a rifle?

RH: The character of the Bohemian doesn’t have its genesis in Raad’s work. Actually I come from a visual arts background, and did my graduate studies in photography. I also worked as a photographer and had the chance to exhibit some of my work. The unconventional story of trying to capture the image of a falling bomb is my story (Madame Bovary c’est Moi! as Flaubert would say).

As a kid, I used to run with my cousin in the streets of Beirut as the bombs were falling, trying to capture an image of a suspended bomb before it landed. It was sheer childhood madness.

But as for Walid Raad’s work, it was made in the absence of any attempt by the Lebanese government to open a dialogue or a reconciliation and truth commission. When the civil war ended, all was ignored; a period of absolute amnesia and denial set in. The only people who were interested in exploring that history were the artists. And I think Walid was one of the earliest artists who attempted to raise the subject. Yes, the work is made of fictions, constructions, maybe because there was no possibility of reconciling the different stories. Every story is contested. There is no national consensus on what took place. It’s still a divided country.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·