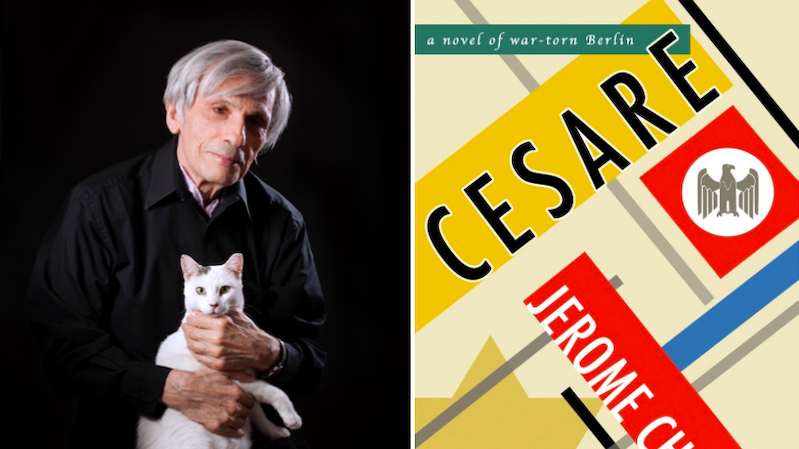

Jerome Charyn’s Cesare: A Novel of War-Torn Berlin is published today. He shares five books that invoke invisibility, noting, “Cesare is a somnambulist, a secret agent who works for the Abwehr, German military intelligence, and seems to wake from the dead as he falls upon his prey. Much of the novel is set in Berlin during World War II.”

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

The Metamorphosis is a novella that defines the endless ambiguity of human values and has left its shuddering mark on the twentieth century. It tells the story of Gregor Samsa, a young insurance agent in Prague, who wakes up one morning as a gigantic bug or cockroach, and depends on his adolescent sister Greta for survival. When Greta stops feeding him, Gregor dies, but Greta herself blooms into a beautiful young woman. Her portrait was based on Kafka’s youngest and favorite sister, Ottla, who ends up in Theresienstadt, the same concentration camp that Cesare breaks into, trying to rescue the woman he loves.

Jane Ciabattari: How do you read Greta’s metamorphosis?

Jerome Charyn: Greta’s metamorphosis is perhaps the most baffling part of the novella. And withdrawn as Kafka was, this is perhaps the real change that he was talking about. Greta starts as a sexless creature and turns into a tigress, as she abandons Gregor for a life of her own. Perhaps this is what had obsessed Kafka: selflessness turning inward upon itself.

The Berlin Stories by Christopher Isherwood

The Berlin Stories is a terrifying book. It consists of two novellas that take place in Berlin during the early 1930s, just before Hitler comes to power, and reveals a city drenched in nightmare, cruel abandon, and even crueler play.

JC: The classic opening line in “Goodbye to Berlin” sets up Isherwood’s narrative stance: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.” How do you think this passive point of view shaped this terrifying depiction of Berlin on the verge of Hitler’s horrors?

JCharyn: Being a camera left Isherwood as a passive, all-seeing eye, who could record the horrors and remain invisible at the same time. It leaves us all in a trance-like state, as we watch the Nazis bloom into a merciless killing machine. And the terrifying, matter-of-fact poetry of the book remains with us long after Hitler’s Germany is gone.

The Pedersen Kid by William Gass

The Pedersen Kid is a novella that tells of the Kid, who is found frozen in the snow on a farm somewhere in the Midwest, and of the family that attempts to revive him. As we move deeper into the story, we begin to doubt the existence of the Kid and of the landscape itself, as if we’ve fallen into an avalanche of words.

JC: This novella, written in 1951, captures Gass’s native Midwest, with its interior viciousness and its killing blizzards, and a family not unlike his own, tormented by the Pa’s alcoholism. The isolation of young Jorge, the narrator, his parents and their farm hand Big Hans, is exacerbated by Pa’s disdain for his Pederson neighbors. As the novella unfolds, Pa insists Jorge and Big Hans come with him by wagon into the storm to check on the Pedersons. But he’s also punishing them for tapping into his precious booze to try to save the Kid. Near the end, Jorge, sitting alone, has one of the most powerful lines in fiction: “I was alone with all that could happen.” How would you explain the ways in which Gass uses language to create a story that is both grounded, through it s specific details, and hallucinatory

JCharyn: This is the magic of William Gass, his utter mastery of language, the poetry of word posed upon word to create a kind of disappearing act, a growing dis-illusion. “I was alone with all that could happen,” says Jorge, who conjures up a world for us like a deepening blizzard, and then has this world disappear with every last particle of snow.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Hamlet is a play that feeds upon total illusion. Hamlet is a somnambulist, like Cesare, and wakes up long enough to almost bring down an entire kingdom. A good part of Cesare takes place on the sea, as Cesare is sent to America on a submarine so that he can morph into a sleeper agent.

JC: Victor Hugo noted of Hamlet, “There is in all his actions an expanded somnambulism. One might almost consider his brain as a formation: there is a layer of suffering, a layer of thought, then a layer of dream.” Is this sort of somnambulism-a combination of suffering, thought and dream—what you have in mind for Cesare?

JCharyn: Exactly. Cesare the somnambulist is caught up in his own somnambulism. He can’t dare to think, yet he thinks all the time. He suffers in a suffering world and then falls into a dream of that suffering. Like Hamlet, he is a killer who stabs into the void. He ends up dreaming of his afterlife with Lisalein the moment he is about to die.

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

Like Ahab, Cesare is also on a quest, not to kill a white whale, but to make himself into an invisible man. I couldn’t have written Cesare without the sad, relentless poetry of Moby-Dick.

JC: If Cesare’s relentless quest is modeled on that of “monomaniacal Ahab,” “crazy Ahab, the scheming, unappeasedly steadfast hunter of the white whale,” what is his underlying motivation?

JCharyn: What motivation can Cesare possibly have in a murderous landscape? He is also hunting the white whale of an ever-shifting reality. His monomania is not so different from Ahab’s. He hasn’t lost a limb, but he has given up part of his sanity. Perhaps Germany itself was the white whale, and Cesare can only tear blindly into its ever-thickening flesh.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·