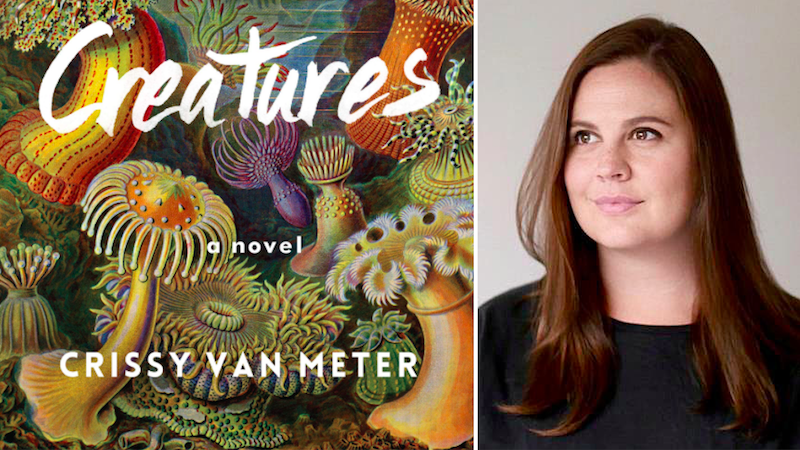

Crissy Van Meter’s Creatures is published this month. She shares five books about wild California.

The Yosemite by John Muir

Poetic and precise, this book is about the most beautiful place on earth: Yosemite.

Jane Ciabattari: Muir’s is gorgeous writing. I love how he describes coming to the “famous Yosemite Valley” on foot:

Arriving by the Panama steamer, I stopped one day in San Francisco and then inquired for the nearest way out of town. “But where do you want to go?” asked the man to whom I had applied for this important information. “To any place that is wild,” I said. This reply startled him. He seemed to fear I might be crazy and therefore the sooner I was out of town the better, so he directed me to the Oakland ferry.

So on the first of April, 1868, I set out afoot for Yosemite. It was the bloom-time of the year over the lowlands and coast ranges the landscapes of the Santa Clara Valley were fairly drenched with sunshine, all the air was quivering with the songs of the meadow-larks, and the hills were so covered with flowers that they seemed to be painted. Slow indeed was my progress through these glorious gardens, the first of the California flora I had seen. Cattle and cultivation were making few scars as yet, and I wandered enchanted in long wavering curves, knowing by my pocket map that Yosemite Valley lay to the east and that I should surely find it.

Looking eastward from the summit of the Pacheco Pass one shining morning, a landscape was displayed that after all my wanderings still appears as the most beautiful I have ever beheld. At my feet lay the Great Central Valley of California, level and flowery, like a lake of pure sunshine, forty or fifty miles wide, five hundred miles long, one rich furred garden of yellow Compositœ. And from the eastern boundary of this vast golden flower-bed rose the mighty Sierra, miles in height, and so gloriously colored and so radiant, it seemed not clothed with light, but wholly composed of it, like the wall of some celestial city. Along the top and extending a good way down, was a rich pearl-gray belt of snow; below it a belt of blue and lark purple, marking the extension of the forests; and stretching long the base of the range a broad belt of rose-purple; all these colors, from the blue sky to the yellow valley smoothly blending as they do in a rainbow, making a wall of light ineffably fine.

Do you have favorite sections?

Crissy Van Meter: I love the sections about winter. A snowy Yosemite is so magical and I love seeing the valley when it’s covered in a white blanket of sparkling snow. There’s a passage in a winter section that describes this exact snowy magic, or what Muir calls a “wonderful winter scene.”

Fancy yourself standing beside me on this Yosemite Ridge. There is a strange garish glitter in the air and the gale drives wildly overhead, but you feel nothing of its violence, for you are looking out through a sheltered opening in the woods, as through a window. In the immediate foreground there is a forest of silver fir their foliage warm yellow-green, and the snow beneath them strewn with their plumes, plucked off by the storm; and beyond broad, ridgy, cañon-furrowed, dome-dotted middle ground, darkened here and there with belts of pines, you behold the lofty snow laden mountains in glorious array, waving their banners with jubilant enthusiasm as if shouting aloud for joy. They are twenty miles away, but you would not wish them nearer, for every feature is distinct and the whole wonderful show is seen in its right proportions, like a painting on the sky.”

I also love how Muir loves and describes the flowers of Yosemite. He’s so good at capturing the seasons, and the life and death of the forest. Something about imaging ribbons of color appearing from what seems like nothing is very appealing to me.

Yosemite was all one glorious flower garden before plows and scythes and trampling, biting horses came to make its wide open spaces look like farmers’ pasture fields. Nevertheless, countless flowers still bloom every year in glorious profusion on the grand talus slopes, wall benches and tablets, and in all the fine, cool side-cañons up to the rim of the Valley, and beyond, higher and higher, to the summits of the peaks. Even on the open floor and in easily-reached side-nooks many common flowering plants have survived and still make a brave show in the spring and early summer.

The Land of Little Rain by Mary Austin

An important voice in the evolution of the American West.

JC: Austin’s book was published in 1903, which means her sense of the inhabitants of the Southwest is based on a time when there were more animals, fewer humans, fewer cities and incursions on her beloved natural landscape. She writes of the pathways traced by coyotes, carrion, miners, Native Americans in the Mojave, of the ongoing search for water. Her collection of stories and essays gives a snapshot of a time long past. Are there parts of her Wild California left today? Where?

CVM: I’ve made the drive from Los Angeles to Las Vegas many times. Every time I travel through the desolate Cajon Pass and make my way to the Mojave high desert, I think of this book. This area still is largely untouched; Hawks swoop overhead, there are few (if any for some stretches) buildings or rest stops. I’ve seen it covered in snow, I’ve seen it as cracked, scorched land. There’s no water. I always imagine that these empty and open spaces, especially the ones in the desert areas, are thirsty and not made for people. I get this sense of openness and emptiness in Joshua Tree, too. And, even in Los Angeles, the desert is bursting through the cracks—the weather, no water, the fires, the dust, literally the desert weeds coming up through the pavement. It’s not so hard to imagine Austin’s California in the city, too.

Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O’Dell

My favorite childhood book, based on the true story of the Lone Woman left behind on an island off the coast of California.

JC: Karana, the protagonist of O’Dell’s book, was based on the only survivor of a massacre of a Native tribe that had settled the island thousands of years before. What is the name of the real island? And what became of the real Lone Woman?

CVM: Of course the real story of the Lone Woman is pretty terrible and sad compared to the children’s book version. The woman was left behind on San Nicolas Island—the most remote of the Channel Islands off the coast of Ventura. After living for nearly two decades alone on the island, the Lone Woman was found by a ship of fur trappers and taken to the Santa Barbara mission where she was christened and named Juana Maria (there’s no record of her real name, ugh!). She got sick almost immediately and later died. She’s buried at the Old Mission Santa Barbara. Karana, the fictional character based on the Lone Woman, is brave and strong and fierce, and I imagine the real woman to be the same. I’d love to visit San Nicholas, but it’s inhabited by the US Navy and not accessible to tourists.

Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana Jr.

Though dense, and sometimes painful to imagine, this book describes early California by Sea in an unaltered state.

JC: Two Years Before the Mast is a classic of a seafaring time, published in 1840, describing Dana’s journey on a sailing ship from to California from Boston during the 1830s. He was a law student, and his voyage into a land that had not yet succumbed to Gold Rush fever displays the riskiness of seagoing life:

A sailor knows too well that his life hangs upon a thread, to wish to be always reminded of it; so, if a man has an escape, he keeps it to himself, or makes a joke of it. I have often known a man’s life to be saved by an instant of time, or by the merest chance,—the swinging of a rope,—and no notice taken of it. One of our boys, when off Cape Horn, reefing topsails of a dark night, and when there were no boats to be lowered away, and where, if a man fell overboard he must be left behind,—lost his hold of the reef-point, slipped from the foot-rope, and would have been in the water in a moment, when the man who was next to him on the yard caught him by the collar of his jacket, and hauled him up upon the yard, with—”Hold on, another time, you young monkey, and be d——d to you!”—and that was all that was heard about it.

Do you find Dana’s book most valuable for its accounts of life on the ocean? Or on shore?

CVM: Dana’s account of the sea is so beautiful, scary, and wild. His journey on the ocean is a constant reminder that the sea, even now, is not something we can necessarily conquer. I am always thrilled by the passages about the sea at night and the silence, and the faint whale songs that lull him to sleep. I feel more attached to the sea view of Dana’s memoir because as someone who gets terribly seasick, I can only fantasize about a long and dangerous adventure at sea.

The Legacy of Luna by Julia Butterfly Hill

A woman lives in a giant Redwood to save the tree, but this book is about truth, and politics, heartache, and the dangers and beauty of wild California.

JC: The author spent two years living in the redwood known as Luna in Humboldt County, beginning in 1997. This is her record. Which aspects of her observations stay with you?

CVM: Hill truly faces so many elements and documents her struggle with and against nature in a way that feels so tangible. The wind! The rain! The cold in her bones. Her fear of falling. It’s a reminder to me of how powerful nature can be, how nature is not something we can or should control. But also it examines the true destruction caused by humans on earth. Specifically, this book is about deforestation, but her account makes me think deeper about how and what we can truly save. It makes me wonder what’s left, and what will truly be here after all the destruction.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·