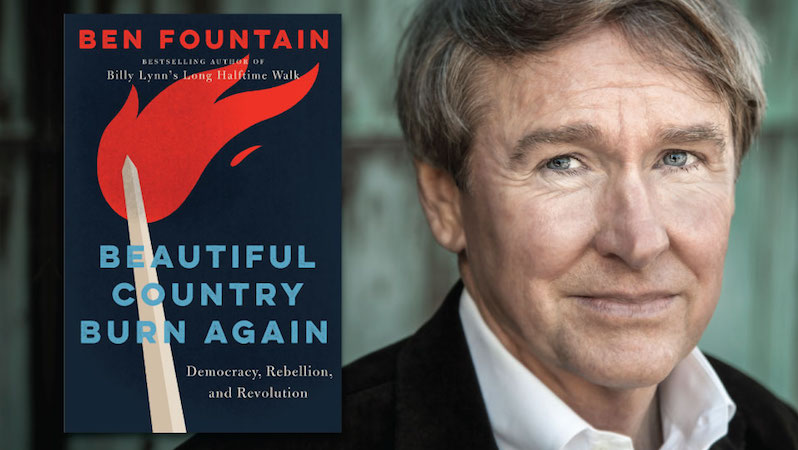

Ben Fountain’s new book, Beautiful Country Burn Again, is published this month. He shares five books that explore American history with Jane Ciabattari.

*

The American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States (sixteen volumes), Robert G. Athearn

I called them “the volumes,” and lobbied mom to buy them for me at the grocery store as they appeared one by one over the course of several years. And she did, bless her; I never had to ask twice. “A knowledge of the past prepares us for the crisis of the present and the challenge of the future,” President Kennedy, or more likely Ted Sorenson, wrote in the forward to Volume I (The New World), but being a half-feral boy in the mid-1960s, I was in it for the pictures, especially of battles, the bloodier the better. More or less by accident, I got a general orientation in American history—dates, people, wars, the rough chronology of things.

Jane Ciabattari: So you got a glimpse of it all, from The New World and Colonial America through The Civil War, Winning the West, The Age of Steel, and up through America Today, which ended, I assume, around the publication date, 1963. What period most fascinated you?

Ben Fountain: I’m sure my interest spun senselessly from one thing to another, but because I was a normal savage little American boy, it was always war that I gravitated toward. I expect whatever “volume” I was spending the most time with had a lot to do with what I’d seen recently on TV or at the movies, usually a portrayal of some form of carnage or another.

Beloved, Toni Morrison

A “historical” novel but not really, in the same sense that William Faulkner said the past isn’t even the past, and James Baldwin pointed out that we are our history, every day of our lives. Far from being an abstraction, American slavery and its legacy are rendered as lived experience, to revelatory and terrifying effect. This book might as well be today’s headlines.

JC: Indeed. It’s as if Morrison cracked open the time capsule of the Civil War and Reconstruction and showed us the savage and horrifying truths and ongoing repercussions of slavery. I can’t think of a novel more important to the telling of this still unresolved conflict in American history. And the ghost of Sethe’s baby daughter is unforgettable. As Sethe’s mother-in-law, Baby Suggs, says, ”Not a house in the country ain’t packed to its rafters with some dead Negro’s grief. We lucky this ghost is a baby. My husband’s spirit was to come back in here? or yours? Don’t talk to me. You lucky.” How do you think her use of the supernatural built the revelatory and terrifying effects?

BF: Well, I’m not even sure it’s supernatural. Human experience is broad enough, weird enough, mysterious enough that it might well be within the scope of “normal” life that we bide with presences that are more in the nature of spectres than “human” beings in the strictest sense. Is Donald Trump an actual human being, or more of an unholy wraith that America has brought upon itself thanks to various and sundry sins? I have to say, viewing the strange young woman of Beloved as straight-ahead realism satisfies my notion of what’s true and authentic in human experience every bit as much as reading her through the lens of metaphor or parable. In fact she’s more terrifying as a “natural,” as opposed to supernatural, phenomenon, and it’s a testament to Morrison’s art that the strange young woman fits so naturally into the America that Morrison portrays.

The Massacre at El Mozote, Mark Danner

Something terrible happened in Salvadoran village of El Mozote in December, 1981, and in his careful, clear-eyed, ultimately damning examination of the event, Danner lays bare the American character. One might consider this book the clinical nonfiction companion to Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, except here the U.S. reveals its genius for outsourcing actual on-the-ground savagery.

JC: El Mozote, Danner writes, “may well have been the largest massacre in modern Latin-American history.” He opens his investigation reporting on the excavation of the skulls of dozens of children and other bodies eleven years after the massacre. Yet, he makes it clear, on-the-ground reporting by Ray Bonner and Alma Guillermoprieto, including interviews with a survivor, appeared on the front pages of the New York Times and Washington Post within six weeks of December 1981. The Reagan administration cast reports of the incident as propaganda, and it was buried for more than a decade. What does this tell us about American history, and the American character?

BF: Well, it wasn’t just the Reagan administration. Practically the entire media establishment pushed back against the reporting of Bonner and Guillermoprieto, including Bonner’s own editor, that great American Abe Rosenthal, who was still denying the basic facts of the massacre some twenty years later, after exhaustive forensics analysis proved beyond all reasonable doubt that the massacre had taken place. The administration leaned hard on the media to follow its Cold War line, and most of the media was only too happy to do so. I think this tells us that there’s a good deal of the sheep in the American character.

We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live (Collected Nonfiction), Joan Didion

History as exposed nerve, a genius intellect registering the subtlest and most profound complexities of experience. Emotion in Didion is information just as worthy of study as sociological data or the archives. Is it history? The best kind; events are sifted and strained through the most exacting of sensibilities.

JC: Certainly 1100-plus pages of Didion’s nonfiction covers a large swath of American history. In the introduction, John Leonard points out that even with Slouching Toward Bethlehem, the first in her chronology, “for every syllable about rattlesnakes and mesquite there was an inquiry into Alcatraz and body bags in Vietnam.” Are there specific historic moments you are particularly taken with?

BF: The lethal accuracy of Didion’s language is what first comes to mind, especially the masterful way she can pluck a mendacious or obfuscating phrase from the mainstream ether and probe it, mash it, shake it, hold it up in all lights and from every angle so that the lie at its core is ultimately revealed. But one moment in particular stays with me: in her piece on the trial of the Central Park Five, she expressed doubts as to the defendants’ guilt, this at a time when their guilt seemed to be a non-issue; that is, the “real” story was in what the horrific rape and assault said about New York City, or American society, or some other large truth. Of course, years later the defendants were exonerated, but Didion was there before anyone else.

The Path to Power (The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Volume 1), Robert Caro

How do things work? Power, money, society, government–to get where he wanted to be, LBJ had to figure it all out, and Caro tells the tale in exemplary (but never boggy) detail. And by the way, rural Texas (along with much of the rest of America) was a living hell by the time Herbert Hoover got voted out of the presidency. The depths of that hellishness, and the salvation offered by the New Deal, has largely been wiped from current American consciousness.

JC: Caro makes it clear how LBJ was able to craft coalitions between wealthy businessmen, who tended to be ultraconservative, and country folk, who he could convince he was a poor man like them. He also was a supporter of FDR and the New Deal (and FDR supported him in return). In the introduction to your book, you note that the New Deal reinvented America—with a “redistribution of freedom, a radical reset of the values in the freedom-profit-plunder equation.” What did the New Deal mean to the Texans who were LBJ’s early constituents?

BF: Well, the farmers, laborers, and small rural townsfolk who were LBJ’s early constituency had been thoroughly plucked and plundered for two or three generations by the time the Great Depression hit. Life in the Texas Hill Country was already marginal at best, and then the Great Depression made it impossible. The miracle of Roosevelt and the New Deal was that the well-being of farmers, laborers, and the middle class would no longer be secondary to the interests of corporations and banks. Roosevelt said that explicitly in an early fireside chat: “of equal importance to banking” were the interests of the farmers. This was an honest-to-God revolution in America, and it saved hardscrabble rural Texas from complete devastation. And saved the country as well, by the way. What it meant to people can be deduced from the fact that Roosevelt was re-elected to three more terms.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·