Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

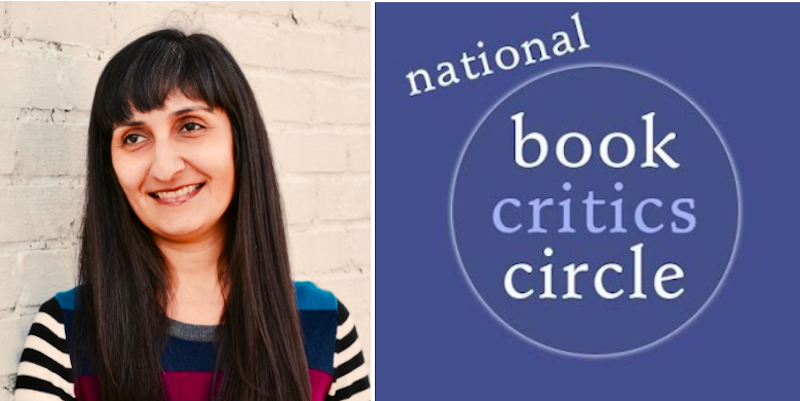

This week we spoke to critic, professor, and National Book Critics Circle board member Anjali Enjeti.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Anjali Enjeti: I had not considered myself a lover of poetry until I picked up Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali. (And I’m not just saying this solely because my first name is part of the title.) Gitanjali was originally published in 1910, which is hard to believe because the verses (also called songs or song offerings) feel so timeless and contemporary. I neither speak nor read Bengali, but the copy I own has an image of Tagore’s handwritten verse in Bengali on the left side of the page and his own translation in English (in type) on the right side. This presentation makes it feel as if I’m discovering his process alongside his words.

Tagore (the first Indian to win the Nobel Prize for Literature) writes verses that feel like a gut punch to the heart. One of my favorites, and one that feels particularly relevant right now, is number 35.

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

AE: Last year I was blown away by two books that got some attention, but not the kind of exaltation I had hoped. The first was Deepak Unnikrishnan’s Temporary People, which won the inaugural Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing. This was, in my mind, a flawless, fantastical collection of short stories that explores national, cultural and emotional identity in the United Arab Emirates, a country that does not grant “guest workers” permanent legal residency. Unnikrishnan unpacks this idea that home and displacement can mean one and the same thing. I read a few reviews of the book, but it flew below a lot of critics’ radars.

The other book is Cristina Garcia’s phenomenal novel in stories, Here in Berlin. I love writers who take chances in the way they structure their books. Here, an unnamed tourist serves as a sort ambulatory therapist for those who divulge their personal histories with Berlin. The chapters are brief and robust. The Holocaust, communism, and the collapse of the Berlin Wall, serve as the book’s haunting settings. Berlin is a city heavily featured in literature, and yet, Garcia found a way to tell its story in an innovative and unconventional way, shedding new light on an old city.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

AE: That we get some sort of enjoyment out of writing negative reviews. Maybe some critics do, but I certainly don’t.

I’ve never outright panned a book, but I have written several very mixed reviews with sharp points of criticism. It’s incredibly stressful for me to do this. I dread it, procrastinate, and re-read the book to make sure that my criticisms are rooted in the text and not my own personal biases, or something I may have heard about the book or author. As a freelance book critic, I have the luxury of being able to pitch the books I’m most interested in reading, or to decline reviewing a book for an editor when I know I won’t enjoy it. So when I realize that a book fails in its delivery, and I have to address it, it pains me. I have so much respect for authors, and for the enormous undertaking involved in writing and selling a book. I’d much rather celebrate a book than criticize it.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

AE: I hope it’s demystified criticism and made it more accessible. And though criticism still has a very long way to go, I hope this greater accessibility has made the field more diverse. I wouldn’t be a critic today if it wasn’t for social media. I didn’t know who or how to pitch. Why would I bother trying to bust into a field that was populated with mostly old white men (and some white women)? But through social media, I discovered the work of other critics of color, and saw reviewing books as a possibility. And I thought, “hey, maybe I can do this, too.”

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

AE: Porochista Khakpour’s reviews are the kind I want to print out, frame, and hang on my wall. I’ve read her review of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian multiple times. She is intrepid, pushing and pulling apart text as if kneading dough. And though she’s thorough in her execution, leaving no stone unturned, she reveals very little plot. How can a critique be both revelatory and mysterious at the same time? This is the goal of a critic, one that few master, but that Porochista seems to accomplish so effortlessly. Early on in “Toward a New Masculinity,” in the summer 2017 issue of Virginia Quarterly Review, she expressed an acerbic though widely-felt sentiment. “This year has challenged me to exist without hating men.” (She would go on to rave about the collections in the review.) Oh, to be so unapologetically fearless and exceedingly fair at the exact same time. It is a thing of beauty in her criticism.

*

Anjali Enjeti is Vice President of Membership for the National Book Critics Circle. She reviews for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the Georgia Review, and the Minneapolis Star Tribune, and teaches creative nonfiction in the MFA program at Reinhardt University.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·