Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Walter Isaacson on Edward Ball’s Life of a Klansman, Kaitlyn Greenidge on Raven Leilani’s Luster, Rumaan Alam on Lorrie Moore’s Collected Stories, Jack Hamilton on Rick Pearlstein’s Reaganland, and Gabino Iglesias on Betsy Bonner’s The Book of Atlantis Black.

“…a haunting tapestry of interwoven stories that inform us not just about our past but about the resentment-bred demons that are all too present in our society today … Because he has few documents, Ball indulges in a lot of surmises and speculations, perhaps a bit too many for my taste … Lecorgne was a minor player in this movement. But for that reason his tale is valuable, both for understanding his times and for understanding our own; he allows us a glimpse of who becomes one of the mass of followers of racist movements, and why … The interconnected strands of race and history give Ball’s entrancing stories a Faulknerian resonance. In Ball’s retelling of his family saga, the sins and stains of the past are still very much with us, not something we can dismiss by blaming them on misguided ancestors who died long ago. ‘It is not a distortion to say that Constant’s rampage 150 years ago helps, in some impossible-to-measure way, to clear space for the authority and comfort of whites living now—not just for me and for his 50 or 60 descendants, but for whites in general,’ Ball writes. ‘I am an heir to Constant’s acts of terror. I do not deny it, and the bitter truth makes me sick at the stomach.’ ”

–Walter Isaacson on Edward Ball’s Life of a Klansman: A Family History in White Supremecy (The New York Times Book Review)

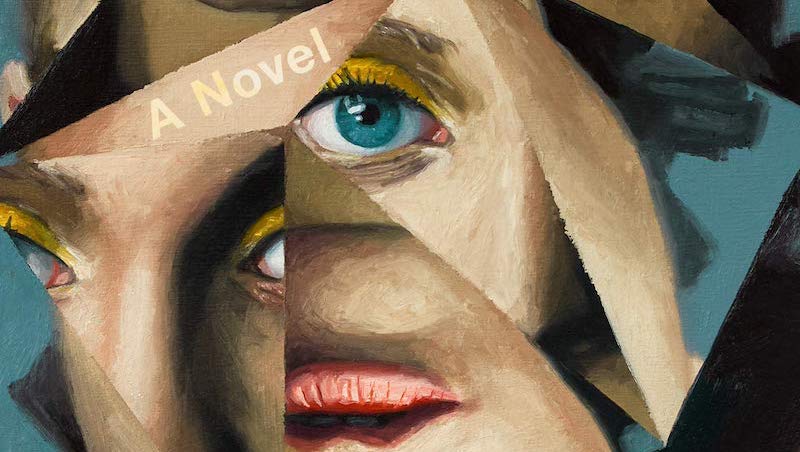

“… nothing if not an ambitious work … Leilani manages to write of Edie’s desire and experience of sex with a clarity and conciseness that is rare in fiction … Even more than a novel about sex, Luster is a novel about what it means to be a black-female flaneur…A black-female flaneur necessarily complicates the position of this character. She embodies the individual that the flaneur usually observes and categorizes. And because of her race and gender, the false promise of an identity disconnected from a class or community is broken by her very nature … Yet this hyperawareness does not lead to action or change on Edie’s part. On the contrary, it seems to stun her into a kind of paralysis … In that the novel begins to falter, as Edie’s self-loathing and disgust mixed with longing toward her adopted family occurs again and again, the same crescendo and intensity of waves for the reader. I do not think it is in Leilani’s desire, as a writer, to have her heroine reach an emotional epiphany … Edie and the rhythms of this novel make so much more sense when you understand them as the pace of a dogged, incessant traveler, watching the worlds she passes through and making rude notes about them, simply to assert the uncomfortable truth that she was there at all.”

–Kaitlyn Greenidge on Raven Leilani’s Luster (VQR)

“In a 2001 interview in The Paris Review, Lorrie Moore mused that the story is perhaps a ‘more magical’ form than the novel. ‘A novel is a job,’ she said, ‘but a story can be like a mad, lovely visitor, with whom you spend a rather exciting weekend.’ Moore’s point of view is the writer’s, but it’s true for the reader, too. Her hefty Collected Stories is a very long weekend indeed, a month of Sundays, mad and lovely … Moore isn’t simply performing black humor, underlining what is horrific about the world. Nor is she trying to disorient, elicit a befuddled chuckle as Barthelme might. It is a laugh in good faith, an attempt to wrest some joy from an unfunny universe. That’s part of why reading Moore is a pleasure—there’s never a worry that the reader might be the butt of the joke … The technical feat of Moore’s earliest stories is language: the efficacy of tart observation as exposition, dialogue that reads as people wish they spoke, the unpredictable deployment of the second person … Moore never promised that art might console us; quite the opposite. In her greatest story, ‘Dance in America’ (1993), a dance teacher is visiting an old friend, Cal, his wife, Simone, and their son, Eugene, who has cystic fibrosis. Cal tells her, ‘It’s wonderful to fund the arts. It’s wonderful; you’re wonderful. The arts are so nice and wonderful. But really: I say, let’s give all the money, every last fucking dime, to science.’ ”

–Rumaan Alam on Lorrie Moore’s Collected Stories (The New York Review of Books)

“Reaganland is terrific, a work whose characteristic insight and soaring ambition make it a fitting and resonant conclusion to Perlstein’s astounding achievement. I think most Americans, regardless of political affiliation, would agree that the effects of the Reagan Revolution are still with us and that in many senses Reaganland is still the place we all live. A hallmark of Perlstein’s work is his blending of political and cultural history, often a tricky balance. Cultural historians (I am one) can sometimes exaggerate the relationship of cultural cause and political effect, while political historians occasionally rely on an overly narrow and deterministic conception of who and what constitutes the ‘political’ sphere. Reaganland chronicles the various tribulations of the Carter presidency while also devoting time to other contemporary events that provide something like a sense of general ‘vibe’ … Perhaps the most significant development chronicled in Reaganland is the emergence of the so-called religious right, in which a socially conservative, theologically populist Christianity became deeply connected to the right wing of the Republican Party … The similarities between the two [Reagan and Trump] are certainly there: the ease with mistruth, the weaponization of nostalgia, the constant framing of America as taken advantage of by the world. But there are also significant differences. For starters, Reagan was an ideologue, through and through. His lies were born of a desire to bend the world to his preferred view of it. While he was often caricatured by his critics as stupid, when it came to issues he cared about, Reagan could become so wonkishly long-winded that his aides had to urge him to dial it down. Trump, on the other hand, believes only in himself and thus lies purely out of self-interest. Trump is also a bully who publicly humiliates his opponents and whose meanness is central to his appeal, while Reagan would jiujitsu opponents so that it appeared that they were unreasonably ill-tempered … Perlstein’s epic achievement of history has finally come to an end, and I hope that someday Reaganland will, too.”

–Jack Hamilton on Rick Pearlstein’s Reaganland: America’s Right Turn 1976-1980 (Slate)

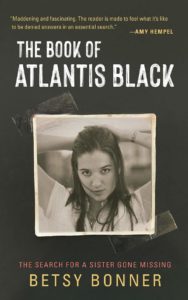

“The Book of Atlantis Black is gripping and works on two levels. On the surface, there is the story of two sisters drifting away from each other and then coming back together. It is a story of siblings dealing with an abusive father who dies of cancer and a mother whose struggles with mental illness ended in suicide. Then there are the true crime elements: petty criminals, police reports, strange men who vanished, Atlantis’ online life and communications with various men after she posted companionship ads, video surveillance showing a couple whom Atlantis is clearly not half of perpetrating some of the crimes she was charged with, and even the fact that she had dated the DEA agent who arrested her. Taken together, these things offer more questions than answers, and each adds a layer to the mystery of Atlantis’ death … It is a book that denies readers the satisfaction of closure, of a final answer and an explanation. Instead, this true crime and memoir hybrid takes us into the heart and mind of Bonner, the one who was left behind, and through her we experience the pain of not knowing—and the frustration of looking for answers even when the person we try to understand was as mysterious as the fabled land of Atlantis.”

–Gabino Iglesias on Betsy Bonner’s The Book of Atlantis Black: The Search for a Sister Gone Missing (NPR)