Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Rumaan Alam on Elif Batuman’s Either/Or, Brandon Taylor on Teddy Wayne’s The Great Man Theory, Alexandra Kleeman on K-Ming Chang’s Gods of Want, Rachel Cooke on Jordan Crane’s Keeping Two, and Joanna Scutts on Damien Lewis’ Agent Josephine.

“The fierce little machines found in the Taiwanese American writer K-Ming Chang’s first collection, Gods of Want…feel so unexpected: Each one is possessed of a powerful hunger, a drive to metabolize the recognizable features of a familiar world and transform them into something wilder, and achingly alive … Chang pushes language into strange, roiling reversals, eroding its given meanings … At times, the rhythmic, idiosyncratic nature of these transformations can feel somewhat repetitive, but the insistent quality of Chang’s aesthetic is a powerful gesture in and of itself … Chang channels the churn, the precarity, the ambient disquiet and threat of disappearance that are part of the émigré experience into sinewy text that mirrors this deep fungibility. It’s a voracious, probing collection, proof of how exhilarating the short story can be.”

–Alexandra Kleeman on K-Ming Chang’s Gods of Want (The New York Times Book Review)

“Cranky characters often make for interesting novels, after all. Consider Saul Bellow’s splenetic heroes: Moses Herzog, Augie March and Artur Sammler. Paul most closely resembles the first of those men, and The Great Man Theory itself resembles Herzog (1964), a novel of complaint directed at various people and institutions in the protagonist’s life … It’s in such moments that Wayne turns the smug woundedness of the contemporary liberal into an amusing social comedy that is, at its finest, a worthy successor to those seriocomic novels of Bellow. The most convincing and interesting part of The Great Man Theory is the way it captures a troubling transformation happening in schools, homes, offices, comment sections and Twitter threads around the world. I don’t mean the insidious ascendancy of the alt-right or the manosphere. I mean the conversion of seemingly enlightened liberals and leftish centrists into hectoring paranoiacs plagued by a shadowy legion of bad actors…He captures both the pitiful and the amusing and the painfully poignant nature of this transformation, how it can hollow out a person … the final turn to melodrama merely feels contrived and false. It renders the novel less smart, less engaging, less human. Wayne had the option to write a real novel about frustrated contemporary masculinity and the ways that white liberal men are also being corrupted by the internet and their lingering sense of entitlement. Instead, what readers will find at the conclusion of The Great Man Theory is that its author has been laughing at them and his characters the entire time. An enraging end to an almost great but ultimately crude novel.”

–Brandon Taylor on Teddy Wayne’s The Great Man Theory (The New York Times Book Review)

“It’s a sequel in which we’re right back where we left off: there’s the deadpan voice, the anthropological insight into American college life in the mid-1990s, the catalog of minor humiliations and grandiose thoughts … Are ideas enough to make a novel? Either/Or is Batuman’s attempt to prove that they are. Forget ‘metacomic,’ Either/Or is a novel that’s also an academic argument for itself as a novel … The voice is intimate and idiosyncratic, the organizing principle diaristic … At first each chapter covers a week, then things pick up and each contains a whole month. This lopsided treatment reflects how youth feels, in my memory anyway—an endless, formless waiting period … Either/Or feels faithful to the experience of growing up; whether we want fiction to depict reality accurately is a separate matter … Batuman is a very funny writer, and funny writing strikes me as the height of intelligence … But the humor here is so insistent, it’s almost a tic. Is it born of a desire to demonstrate the narrator’s intelligence, or, worse, does it expose you as stupid if you start to get tired of it? … The novel’s emotional impact relies on the reader’s distance from her own youth; we understand that time’s passage is inevitable and hope it will be kind to Selin … I cannot deny that Batuman is a confident litigator. Her novels anticipate whatever criticism I might offer. And though I laughed a lot while reading, I worry even now that I’m missing part of the joke. Maybe I’m the idiot.”

–Rumaan Alam on Elif Batuman’s Either/Or (The New York Review of Books)

“There’s a good reason why Jordan Crane’s amazing new graphic novel, a gorgeous-looking book that comes with rounded corners and thick ivory paper, looks a bit like an expensive journal. Keeping Two is indeed a kind of diary, its narrative comprised almost entirely of the innermost thoughts of its two characters. Just as in a diary, nothing much seems to happen for pages at a time and yet everything does … isn’t a straightforward read. Crane, an award-winning cartoonist, is ambitious for his medium and his narrative shifts constantly between past and present, fantasy and reality, with a speed that can be confusing; every page – every frame – is bathed in a bright, leafy green and this sometimes makes it hard to read characters’ emotions (after a few hundred pages, it’s pretty tiring on the eye too). But it also repays patience, its powerful climax at once deeply connected to, and utterly at odds with, the frustrating detours that precede it. If it is, at moments, about claustrophobia and loss, its larger message has to do with human connection: how we long for it and yet how easily we take it for granted.”

–Rachel Cooke on Jordan Crane’s Keeping Two (The Guardian)

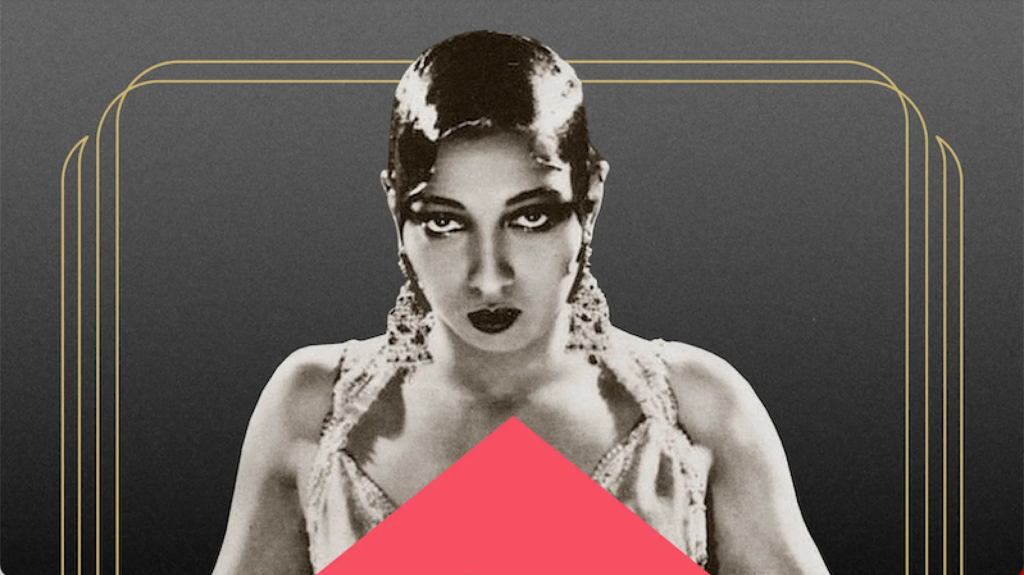

“Given the value, danger, and sheer flamboyance of Baker’s spying activities, it’s a shame that she hasn’t found a better chronicler of her exploits or her complicated history. For Agent Josephine, Damien Lewis, the British author of several works of military history and biography, dug into hard-to-access archives and the chronicles left by key players to create an account that is long on detail but sadly lacking in psychological insight or storytelling panache … Despite Baker’s nominal centrality, Lewis is more comfortable with the male characters in her story, whom he’s able to fit into familiar story arcs … for a writer such as Lewis, apparently steeped in Fleming’s work, there’s a constant hum of astonishment that Josephine Baker would, or could, work as a secret agent … The specifics of her espionage career are remarkable, and certainly worth the telling—both in this form and in the screen adaptation this book has its eye on throughout. But what’s truly remarkable is that she was so consistently underestimated. Josephine Baker was a spy all along.”

–Joanna Scutts on Damien Lewis’ Agent Josephine: American Beauty, French Hero, British Spy (AirMail)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.