Our basket of blazingly brilliant reviews this week includes Philippa Snow on Megan Nolan’s Acts of Desperation, Parul Sehgal on Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s Francis Bacon: Revelations, Laura Marsh on Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth: The Biography, Suraj Yengde on Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, and Kali Fajardo-Anstine on Carribean Fragoza’s Eat the Mouth That Feeds You.

“A new, furious novel about a failed romance by the writer and essayist Megan Nolan, Acts of Desperation, appears set to haunt its readers in a similarly merciless and unrelenting fashion: It is frightening and feverish, compulsive and distressing, and as true-seeming a document of toxic and manipulative love as any published within memory … It has been compared to Sally Rooney’s Normal People numerous times in blurbs and in reviews by dint of its having been written by a millennial woman who is Irish, and because it is a novel about doomed, millennial love. The equivalence, I think, does not ring true: Where Normal People is exacting, cool, and dilatory, and minimalist in its style, Nolan’s book is nakedly emotional, passionate rather than dispassionate, and sometimes maximalist to the point of feeling reassuringly unfashionable … a frightening passion animates the novel, so that whether or not any of its ugliest or most degrading scenes are based in fact, what remains is a sensation of uncanny voyeurism, as if reading it were tantamount to having experienced something nearly catastrophic.”

–Philippa Snow on Megan Nolan’s Acts of Desperation (The New Republic)

“He seemed to explode out of nowhere from the rubble of postwar Britain—an untaught, untamed figure, bearing paintings of flayed flesh and distorted mouths, with an aura of dark ceremony, the scent of incense and the abattoir. This is the Bacon we know—creature of Stygian charm in dandy’s garb, whose own face was flayed by lovers, who flung him out of windows in the beatings he sought. His influences were Nietzsche and Aeschylus; his mode, ‘exhilarated despair’ … The authors, so frank on de Kooning’s private life, turn prim and almost anthropological when it comes to Bacon—and not even on the rough stuff. I began to hear the sentences in David Attenborough’s voice … Happily, this leviathan of a book (just shy of 900 pages), contains at least a half dozen more profitable arguments. It is the most comprehensive and detailed account of the life, and one that topples central pillars of the Bacon myth.”

–Parul Sehgal on Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s Francis Bacon: Revelations (The New York Times)

“In Bailey’s telling, Roth’s life is a story of a great talent, threatened by other people’s desires and demands. … Much that Bailey writes about Martinson is difficult to stomach … Women in this book are forever screeching, berating, flying into a rage, and storming off, as if their emotions exist solely for the purpose of sapping a man’s creative energies … From book to book, Bailey expresses Roth’s disappointment at uncomprehending reviewers and prize juries—where’s that National Book Award? And how about that Pulitzer? In his personal life, which Bailey documents fling by fling, Roth now often turns to sensible, accommodating women … Then again, Roth does not come out of this biography looking so great, either, despite getting the chance to tell his side of the story. His final years see a sad procession of young girlfriends floating in and out of his life, as he tries to convert some of them into long-term carers … Possibly the worst thing you could do for Roth’s reputation would be to defend him on his own terms. His emphasis on settling scores with ex-wives and lovers draws attention to his signal failures of imagination—his lack of interest in the inner lives of women, his limited ability to reconcile his own experiences of pain with the co-existence of others’ suffering … In Bailey, Roth found a biographer who is exceptionally attuned to his grievances and rarely challenges his moral accounting. Yet the result is not a final winning of the argument, as Roth might have hoped. Just as his unpublished rebuttal to Claire Bloom made him sound like a bully, this sympathetic biography makes him a spiteful obsessive.”

–Laura Marsh on Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth: The Biography (The New Republic)

“By fusing the narratives of escapade, hope, and refugee settlement, Wilkerson highlights the stories of intra-migrants who contributed to American art, literature, and humanities. Wilkerson is a chronicler of dying memories. She does this work with the passion of a historian, the dedication of an archivist, and a journalistic flair. This book is a compilation of America’s quests to find answers to itself. What is slavery in a context of dispossession, exploitation, capitalism, and immovable hierarchy? It has to mean something more than merely the eighteenth-century imaginative theories of a few Europeans. To correctly realize itself in the oppressive characterization of power, a postbellum politics of sophistication underscored the caste paradigm to make sense of the extremely complex and still-forming American society … Wilkerson has flicked the tip of a volcanic mountain with her index finger. This is going to open a Pandora’s box of deeply buried and layered expressions of human anger, frustration, and atrocity. Wilkerson has brought us to witness the magnitude of oppression that any society will commit upon its lowest castes. Beyond the particular experiences of being African American, Jew, or Dalit, this universal experience occurs across all societies. The specific oppressions need to be appreciated through caste dictions.”

–Suraj Yengde on Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (The Baffler)

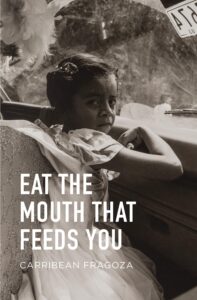

“In these 10 fabulist tales, the body and the inevitability of loss shimmer, and each story moves effortlessly between horror and the real. In the tradition of Surrealists like Leonora Carrington, who once wrote, ‘Houses are really bodies,’ Fragoza has plunged into the depths of her characters’ psyches and the unruly abodes in which they now find themselves … physicality becomes a vehicle for the grotesque with descriptions that push the reader’s comfort and conception of the body … But these stories also expand the way we perceive the confines of our earthly vessel … While this is Fragoza’s debut book, she has been published widely as a journalist…her work focusing on Chicano culture and identity in Southern California. That region glistens in this collection.”

–Kali Fajardo-Anstine on Carribean Fragoza’s Eat the Mouth That Feeds You (The New York Times Book Review)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.