Our Fab Five this week includes James Parker on Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth: The Biography, Brandon Taylor on Michael Lowenthal’s Sex with Strangers, Leo Robson on Sarah Moss’ Summerwater, Kevin Baker on Thomas Dyja’s New York, New York, New York, and Divya Subramanian on Thomas Healy’s Soul City.

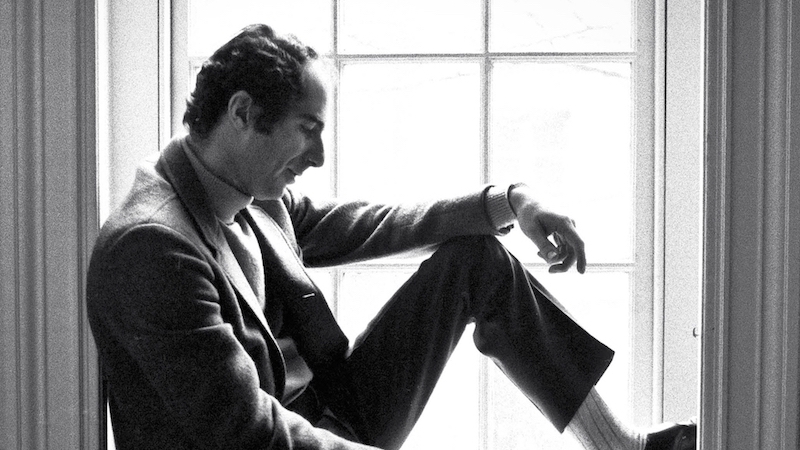

“Was there ever a novelist who was more of a novelist than Philip Roth? More of a long-haul moralist, more of a titanic grump, more of a sex fiend, more of an industrial reality-processor, more of a deskbound hero, more of a get-up-early-and-feed-your-life-into-the-grinder (even if your back is killing you) type of guy? His prose is prose, definitively prose, anti-felicitous and slightly barbarous. No Updikean grace notes, no heavenly Bellow-isms, no glassy Cheeveresque rhapsodies. When it’s bad, it’s mechanical. When it’s good, it’s biblical: stacked clauses and surging power and a shaking of fists at the skies … Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth comes flapping at us like a magnificent albatross through the mist, a heavy, feathery projectile from beyond the rim of time … Bailey is a very good writer and a very good literary biographer … I think it’s unlikely that Philip Roth gets Philip Roth wrong. Bailey certainly lets the repellent in, and along with it comes the man in his wholeness … By the (very moving) end of Philip Roth, the sex drive and the writing drive both having finally ebbed, Roth is ready to go: ‘Boy, am I getting tired of my resilience.'”

–James Parker on Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth: The Biography (The Atlantic)

“Michael Lowenthal’s new story collection, Sex With Strangers, is nimble in its particulars. The stories take place in gay clubs, on cruises, along beautiful beaches and in humble small-town kitchens. His characters are men and women, gay and straight, at home and abroad, beautiful and less beautiful than they once were. There’s an ease to his storytelling, too. Nothing feels strained, and the stories slow down and speed up until their climaxes arrive with a weirdly deadening ambivalence … Lowenthal is a sensitive chronicler of the tensions that animate a life. But there’s also a mean streak running through the book … In the early 2000s, there was something particularly fatalistic about the onset of one’s 30s for gay men. It seemed to pervade much of queer popular culture, that to turn 30 marked the sharp drop in one’s value on the meat market. Youth and beauty had a kind of moral force. This theme dominates the stories in Sex With Strangers, sometimes successfully…But more often than not, Lowenthal’s gaze seems to delight scornfully in his characters’ physical flaws.”

–Brandon Taylor on Michael Lowenthal’s Sex with Strangers (The New York Times Book Review)

“Summerwater, though smaller in scale than most of her previous works, exhibits many of her strengths and preoccupations. In tracing her characters’ finicky, circular, weather-obsessed thoughts (‘Ostentatious rain. Pissing it down’), Moss touches on—or, more accurately, brushes past—the Brexit vote, Anglo-Scottish relations, climate change, the concept of rape culture, overpopulation, adolescent depression, and, if not exactly warfare between the generations and the sexes, then at least mutual incomprehension and froideur. The cast of characters proves usefully broad; of the book’s dozen perspectives, each rendered in a colloquial free-indirect style … The novel is powered not by the local tensions it depicts but by the existential conflict underpinning them. When we write about the behavior of a society, Moss seems to say, we are also talking about the workings of the individual mind; collective myths—nostalgia for a pre-industrial past and an unmixed populace, the dream of a sovereign future, some settled story about our present moment—are simply drives and fears writ large … It’s hard to miss that the novel follows Ghost Wall in turning from the brashness of daily life toward a more remote or enclosed realm, in closer touch with human atavism—and also, perhaps, with what really matters to this brilliant, confounding writer.”

–Leo Robson on Sarah Moss’ Summerwater (The New Yorker)

“You will have a hard time getting through Thomas Dyja’s New York, New York, New York, mostly because there is an idea on every page, if not in every paragraph—and usually attached to a perfect line from the host of sources he has collected for this history of New York City over its last four rollicking decades. Here is the journalist Michael Tomasky fretting that ‘there’s only so much wholesomeness New York can take,’ the graphic designer Tibor Kalman advising us that Times Square ‘should be a zoo, like the rest of New York, but a well-maintained zoo instead of a depressed, unemployed and crack-smoking kind of zoo,’ and the philanthropist Andrew Heiskell promising a crime-free Bryant Park: ‘All the hiding places have been eliminated.’ Here is Spy magazine headlining Rudy Giuliani as ‘The Toughest Weenie in America,’ Jules Feiffer calling Elaine’s ‘a men’s club for the literary lonely,’ the writer Lewis Lapham diagnosing money as ‘the sickness of the town’ and the architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable calling Harry Helmsley’s Palace Hotel tower ‘a curtain wall of unforgivable, consummate mediocrity’ … What he has produced is a tour de force, a work of astonishing breadth and depth that encompasses seminal changes in New York’s government and economy, along with deep dives into hip-hop, the AIDS crisis, the visual arts, housing, architecture and finance.”

–Kevin Baker on Thomas Dyja’s New York, New York, New York: Four Decades of Success, Excess, and Transformation (The New York Times Book Review)

“Soul City would be open to residents of all races but designed to help Black residents through a combination of cultural uplift, jobs, and egalitarian social policies. Far from a quixotic vision or separatist fantasy, Soul City attracted interest from across the political spectrum: McKissick secured $14 million in federal urban renewal funding to bankroll the project, thanks in part to his assiduous courting of the Nixon administration. Indeed, the question that lingers around Soul City is not why it failed, but how it came so close to becoming reality … Soul City would address urban deprivation by reversing decades of out-migration from the rural South. And it would embody the self-sufficiency prized by the new face of the civil rights movement—Black Power … Why revisit an episode like Soul City? Healy states that his goal ‘is not to assign blame. It is to understand the forces that led to its failure and the lessons it offers for the pursuit of racial equality today.’ The real factor behind the project’s demise was not simply racism, he contends, but the suffocating grasp of white power—’the control of white society over the lives of Black people’ … The tale of Soul City thus stands as a powerful—particular, vivid, and easily grasped—rebuke to narratives that deny the effects of structural racism.”

–Divya Subramanian on Thomas Healy’s Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia (The New Republic)