Our feast of fantastic reviews this week includes Nicholas Mancusi on Salman Rushdie’s Victory City, Jessica Pressler on Pamela Anderson’s Love, Pamela, Hannah Gold on Patricia Highsmith’s Diaries and Notebooks, Ben Fountain on A. M. Homes’ The Unfolding, and Alexandra Jacobs on V (formerly Eve Ensler)’s Reckoning.

*

“Rushdie’s relentless creative energy pairs well with his understanding of how history ‘works,’ and (excepting the occasional magic spell or gift of flight) this book can read almost more like a work of history than a fairy tale. So call it a feat of fidelity that later sections grow confusingly byzantine and the history lesson drags at points … What Rushdie re-creates convincingly is the way that the divine is a necessary component in the creation myths of great cities and societies. The urge to understand ourselves in sacred terms developed not from the invention of history, but alongside it. It’s as if Rushdie has dropped a molecule of divinity into a petri dish containing the other basic stuff of life, and watched a civilization cultivate.”

–Nicholas Mancusi on Salman Rushdie’s Victory City (TIME)

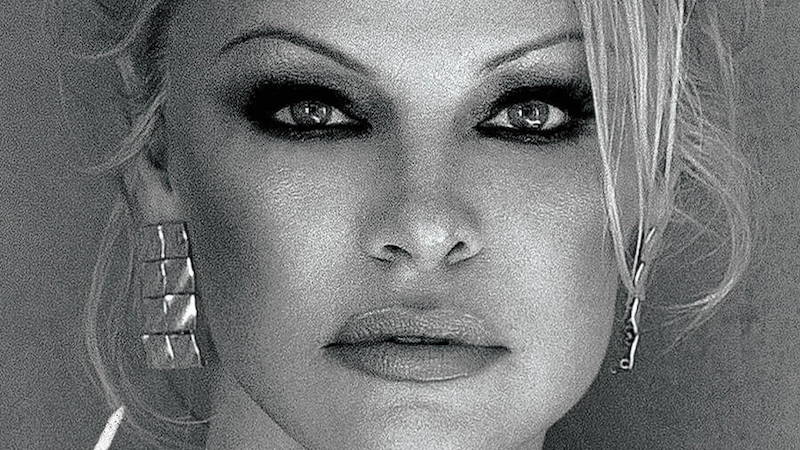

“The most disappointing thing about Love, Pamela is that it doesn’t come in a form that can be injected directly into your veins … Anderson is a natural storyteller, which shouldn’t come as a surprise; her ability to sustain a personal narrative is what’s kept her in the public eye for going on four decades. Love, Pamela is a dazzling and occasionally dizzying ride through this period, in which vivid scenes of ’80s and ’90s decadence bump up against blind items about Russian oligarchs and brief but iconic celebrity cameos … Woven throughout are passages written in verse, which is not as annoying as it sounds: There’s so much going on that you need the extra line breaks to catch your breath … She’s been in something like 20 movies and 60 TV shows, and still found time to marry Kid Rock on a yacht, get drunk with Julian Assange and persuade Vladimir Putin to save 12 beluga whales. Recently, she was photographed dragging a Christmas tree through the streets of Paris in a fluffy white dress and matching hat. Evidence enough that Pamela Anderson has been living the dream, one fantasy at a time.”

–Jessica Pressler on Pamela Anderson’s Love, Pamela (The New York Times Book Review)

“By her twenties, Highsmith already feels that time is running out to prove herself a writer of genius like Thomas Mann; she fears that instead she’ll wind up like Kafka, who, by her lights, wasn’t quite wonderful enough. She loves Dostoyevsky, and it’s in his detailed psychological portraits of criminal and heretic minds that she picks up her habit of overusing exclamation points in her personal writing…Highsmith wears many faces, and taken together they’re a tough crowd to impress … Adrift on such violently contradictory emotions, Highsmith’s diary entries seem straightforward, even axiomatic, when looked at in isolation, but together they inspire a sharp sense of suspense. They’re a social calendar written in the style of a noir, with Highsmith never failing to come off as both femme fatale and starched-shirt detective … The diaries, with all their passions and reversals, reveal Highsmith’s determination to carve herself like a sculpture using words as her material. Her abiding conviction is in her worth as an artist and an individual, which she rarely doubts. Only the cost of this conviction—the amalgamation of skill, cruelty, and self-sacrifice that it will demand—eludes her, much as she strives to appraise it … Reading the New York diaries feels like bearing witness to a version of Highsmith that she largely managed to destroy.”

–Hannah Gold on Patricia Highsmith’s Diaries and Notebooks: The New York Years, 1941-1950 (The New Yorker)

“Even when dressed up in a tux, racism in America isn’t usually as polite as Homes presents it in The Unfolding. Then again, manners can furnish a civilized veneer to what are basically bare-knuckle power plays … Homes puts a good deal of this kind of bloviation into the mouths of the Forever Men, sentimental arias bursting forth amid their running volleys of frat-house taunts and jibes. Much of the book is written in the key of satire, and this feels right; hard to conceive of a satire-free novel about twenty-first-century American politics, given the frankly bizarre raw material. Homes has only to nudge the Big Guy a bit to achieve a working caricature of the ultra-privileged white male…but whether satire is incidental to the story, or its organizing principle, is, for much of the book, an open question. Should we be mainly amused, or mainly horrified? … The book offers a through line of old white men fretting that old white men will soon be obsolete, but little sense of the visceral feeling, the lived experience of it. For a coup to be in the works, surely something powerful is stewing here, some awful racist roux of anger, fear, confusion, and defiance that this election, unlike all the ones that came before, has brought to boiling. Assuming that racism is truly the heart of the matter, the novel is obliged to crack it open if it means to do us any good—if it’s to tell us something real about ourselves. I found myself thinking of Norman Mailer’s Miami and the Siege of Chicago (1968)—written precisely forty years before Obama’s election—and the excruciating dive Mailer takes into his inner racist…Maybe his kind of flaying assessment is just too fraught for our times, even at the remove of fiction. Maybe only the most daring, or reckless, or naive white writer would undertake such a project these days, but this caution leaves a hollow at the core of The Unfolding, and the novel suffers for it.”

–Ben Fountain on A. M. Homes’ The Unfolding (The New York Review of Books)

“For those familiar with Ensler’s work, much of Reckoning will feel like a jagged replay of her core stories … In apparent refutation of the patriarchy V wants passionately to upend, Reckoning obeys no conventional chronology or form. It’s collaged together with concepts—the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, for example, is linked to birds falling from the skies in 2020—and exhibits a woman drawn inexorably, as if in repetition compulsion, to sites of even worse suffering than her youth. It’s a kind of Choose Your Own Abomination, from Covid to the concentration camp of Theresienstadt to Congo … ‘One is always failing at writing,’ V acknowledges, in a sentiment any writer understands. And indeed Reckoning is, if not a failure, kind of a bloody mess, but defiantly, provocatively, maybe intentionally so. It exhorts readers to confront the worst and ugliest, pleads for progress and peace, and provokes admiration for its resilient, activist author. V shall overcome, someday.”

–Alexandra Jacobs on V (formerly Eve Ensler)’s Reckoning (The New York Times)