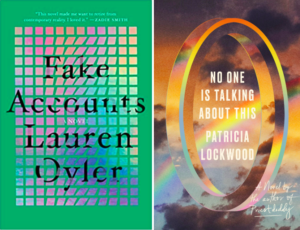

This week’s slate of superior reviews includes Claire Fallon on Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts and Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This, Jillian Steinhauer on Abraham Riesman’s True Believer, Hannah Giorgis on Chang-rae Lee’s My Year Abroad, Parul Sehgal on Sonia Faleiro’s The Good Girls, and Maureen Corrigan on Vendela Vida’s We Run the Tides, and

“One of the most demoralizing aspects of spending half of my time on social media is that it makes me worse company for myself. In search of good posts, and lured by the prospect of finding my own occasional posts deemed good themselves, I willingly bathe my brain in the poisonous slurry of bad tweets, subtweets, thirst traps and indecipherable memes…I don’t like spending time with my brain when it’s like this: narcissistic, defensive, trivial. This is one of the great challenges in addressing social media in fiction…It reflects a part of our life that feels wasteful of time and energy, that tends to leave us feeling itchy and alienated, both from others and ourselves. In two almost mirror-image novels, critic Lauren Oyler and poet Patricia Lockwood have shouldered the task of turning the particular brain poisoning acquired online into literature. Both books—Oyler’s relentlessly wordy satire Fake Accounts and Lockwood’s deeply felt, fragmented novel No One Is Talking About This—are dazzling, devastatingly funny and sharply observed accounts of life on and around social media. They’re also case studies in how difficult it is to write fiction that gives us real insight into our brain-parasite-like relationship with social media without giving us the same bone-deep sense of self-loathing and futility as six hours of scrolling Twitter.”

-Claire Fallon on Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts and Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This (HuffPost)

“While a person in his eighties can be forgiven for not managing to re-create the glories of his earlier career, the failures of Lee’s last two decades point to a through line in True Believer: The man hailed as brilliant had a lot of bad ideas, not simply in terms of marketing, but in content and execution. He was obsessed, for instance, with the idea of publishing collections of found images with comedic captions. (One example: a woman who stands beside Marilyn Monroe and exclaims, about her breasts, ‘They’re real!’). The concept is basically a proto-meme—which has potential. But for Lee it never landed, probably because the pairings were not funny. … In light of this, it’s only natural to ask: Could Lee really have invented all those Marvel characters on his own? Riesman doesn’t make a judgment either way, but I get the sense that he’s doubtful, as am I after reading his book. ‘Stan was a man whose success came more from ambition than talent,’ he writes. Lee’s ambition was to reach the top, which he did thanks in large part to his skill at self-promotion and his charm … Lee may have done groundbreaking work, but his personal version of heroism was, at heart, old-fashioned: He envisioned himself as an icon who, by his own doing, redeemed some small part of the world. He believed not just in his own myth but in that of America: a place filled with well-intentioned, bootstrapping individuals who shape their own destinies. And the superhero genre, even Stan Lee’s version of it, propagates this national narrative, with its focus on strong men, its simplistic visions of good versus evil, and its glorification of justifiable violence.”

–Jillian Steinhauer on Abraham Riesman’s True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee (The New Republic)

“An exuberant picaresque in style, My Year Abroad is thematically a study of human consumption, and the kinds of people who benefit from it … Smaller crises also crop up throughout My Year Abroad, an ambitious work that sows an exhilarating sense that something could go wrong at any turn. More than malice, the characters’ ennui is what threatens their well-being. That relatable boredom makes My Year Abroad a curious quarantine read. Following along with Tiller’s international—if sometimes unsavory—adventures, I found myself wishing I could fly off … nearly anywhere. The trick—and delight—of Lee’s novel is that it forces readers to sit with their confusing desires, to question the appeal of the things we don’t or can’t or shouldn’t have … To Lee’s credit, he explores this human impulse not through self-conscious inquiry, but through wildly creative, adventurous storylines … Hunger—to belong, and for belongings—drives the primary conflicts in My Year Abroad. Whatever they’re looking for, the characters find trouble when they let the intensity of their desires cloud their judgment … In that sense, My Year Abroad prompts the same hunger its story implicitly criticizes: Even at the end of a jam-packed tale, it’s hard not to want more.”

–Hannah Giorgis on Chang-rae Lee’s My Year Abroad (The Atlantic)

“When Faleiro began visiting the village in 2015, it was to research a planned book about rape in India. But the case cracked open to reveal a honeycomb of histories, resentments, secrets, competing interpretations. The nature of the crime kept shifting. Was it murder or suicide? The families of the girls laid the blame on a local boy and his kin, of a more powerful caste. This was a story of caste violence, it was decided. No; the police began suspecting the fathers. This was, in fact, a story of honor killings—of a world in which ‘reputation was skin’ and ‘the taboo against premarital sex was greater than the stigma of rape.’ Or was it a news story, about the proliferation of soap opera narratives and the Indian media’s taste for them? Or a story of jagged modernization, of a country in which cellphones were cheap and ubiquitous but toilets scarce? … we glide swiftly, smoothly, only to realize that we’re not approaching a clearing but being led into a darker, more tangled story … The Good Girls is transfixing; it has the pacing and mood of a whodunit, but no clear reveal; Faleiro does not indict the cruelty or malice of any individual, nor any particular system. She indicts something even more common, and in its own way far more pernicious: a culture of indifference that allowed for the neglect of the girls in life and in death.”

–Parul Sehgal on Sonia Faleiro’s The Good Girls: An Ordinary Killing (The New York Times)

“The year is probably too young to make this kind of pronouncement, but the new novel I know I’m going to be rereading in the coming months and spending a lot of time thinking about is Vendela Vida’s We Run the Tides. It’s a tough and exquisite sliver of a short novel whose world I want to remain lost in—and at the same time am relieved to have outgrown … Eulabee speaks to us in present tense, which makes her voice, coming to us from the dim reaches of 1984, more poignant, because even as we’re listening to her we know that yearning girl doesn’t exist anymore … There are so many moods and story currents running through this wonder of a novel … Female adolescence in this novel feels like being sucked out to sea. It’s overwhelming, absurd and dangerous and even the best adults can’t help. Eulabee and her friends have to figure out how to swim back to shore all on their own.

–Maureen Corrigan on Vendela Vida’s We Run the Tides (NPR)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.