Our fantastic five this week includes Parul Sehgal on the fraught letters of Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Hardwick, Patricia Lockwood on Edna O’Brien’s new novel, Chelsea Leu on Jeff VanderMeer’s dark dystopia, Josephine Livingstone on Carmen Maria Machado’s dream house memoir, and Kevin Young on the career of Ralph Ellison.

“Adrienne Rich—one of Lowell’s closest friends—inveighed against him with fury. ‘What does one say about a poet who, having left his wife and daughter for another marriage,’ Rich wrote in a review, ‘goes on to appropriate his ex-wife’s letters written under the stress and pain of desertion, into a book of poems nominally addressed to the new wife?’ She went on to call Lowell’s eloquence ‘a poor excuse for a cruel and shallow book.’ Cruel, shallow—and a success. The Dolphin won Lowell his second Pulitzer Prize. And Hardwick was pushed to the brink of suicide … Hamilton makes the case that core to the couple’s letters in the 1970s and their work during that time ‘is a debate about the limits of art—what occasions a work of art; what moral and artistic license artists have to make use of their lives as material’ … What makes the letters so darkly compelling, and such uneasy, thrilling company, is a different concern—the very one, in fact, that Hardwick pursued in all her writing, whether on Ibsen’s heroines or on the civil rights movement. It is the elemental question of motive. Why do people do what they do? How much do they understand their own impulses and responsibilities?”

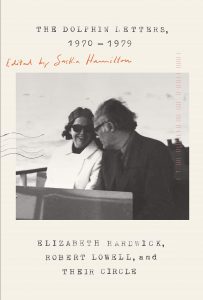

–Parul Sehgal on The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979: Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell, and Their Circle, Ed. by Saskia Hamilton (The New York Times)

“…she has always been attracted to stories of girlhood rupture, and perhaps more important, to the mechanics of community ostracism that often follow in their wake. As a writer, she appears to be hyperfocused on the individual, down to the lights in the hair and the pores of the skin, but she always moves out to show the family, the village’s immune response to a wound on the communal body … The real mistake, seen so often in travel writing, is to set foot on the promontory of an unfamiliar country, let a photogenic wave crash over you, and present yourself as the discoverer. O’Brien hasn’t done that here. Instead, some texture is absent from the Girl’s inner monologue, from the self-mythology that chants in the background of experience. There is a thinness, as if every third word is missing, which does odd things to her patented rich rhythms. While this could be waved away as the language of shock, trauma, being prised apart by unknown hands, it isn’t quite – and anyway we can’t know, since we don’t hear the voice of the Girl before she has been kidnapped. It is more the language of first encounter. If the Girl’s interior is a forest, neither do the trees there have names. Landscapes breathe out a book’s oxygen, and we turn a little blue here … Survival instinct alone drives the Girl. Her life bites at her heels, and not a single choice she makes seems to spring from a distinct personality – and when that’s true, you don’t have a novel, you have a nature documentary, where a soothing voice narrates the fate of far-off prey … a distrust enters into the reading. Would Maryam really describe one beautiful girl’s braids as snakelike, and another’s as being little serpents? … in this context she does not know, so the narrative, instead of riding alongside like a horse or walking arm in arm with the main character, is a room lit by a single bare bulb, where the author is asking the Girl questions. Like this, was it like this, would it be like this? She does not have enough time with her; there are thousands of questions she will not get to ask.”

–Patricia Lockwood on Edna O’Brien’s Girl (The London Review of Books)

“…there’s more than a touch of Hieronymus Bosch in this darkly transcendent novel filled with phantasmagoric visions, body horror and tortured beings traversing a blasted desert hellscape. Think “The Last Judgment,” but with more animals … Dead Astronauts pointedly inhabits these strange, nonhuman consciousnesses … Violence and horror and death suffuse the book, in a cyclical, inevitable pattern perpetrated mostly by humans who don’t value other forms of life … Amid all its grimness, the novel finds some small redemption in the power of love. But VanderMeer’s brilliant formal tricks make love feel abstract and unconvincing by the end, a flimsy human ideal. Late in the book, the blue fox recalls his capture by the Company, staring into his mate’s eyes as he’s dragged away from her. ‘The sentimental tale,’ he tells us coolly. ‘The tale you always need to care. Which shows you don’t care. Why we don’t care if you care.’ It’s precisely that ferocity that makes Dead Astronauts so terrifying and so compelling.”

–Chelsea Leu on Jeff VanderMeer’s Dead Astronauts (The New York Times Book Review)

“In the Dream House refashions the gothic heterosexual house of horrors into a place where the queer, abused woman can speak in many voices, including her own … Machado is not a Victorian waif in a nightgown or a straight woman; she wasn’t forced to stay in the home she shared with the ex. On the face of it, the story’s queerness makes Machado’s use of a haunted-house motif a counterintuitive choice. But that very paradox is the subject of In the Dream House: A prison can have unlocked doors. It’s a maddeningly complex proposition, although, like all paradoxes, it seems simple enough from the outside … As the house falls apart under her memory’s scrutiny, Machado works like a kind of forensic carpenter, sifting through the wreckage for what went wrong … Machado’s strategy disorients the reader, but that feels like an intentional choice. After all, a person always feels disoriented within their own biography: Nothing quite makes sufficient narrative sense at the time it is happening, but the fragments layer upon one another to form the story of a life … There are hundreds of ways to be haunted, In the Dream House shows, but not all of them have been written: Via a delicate polyphony of storytelling and criticism, Machado lays out how the literary tradition of domestic abuse has both expressed and muffled the experiences of women in danger in their own homes.”

–Josephine Livingstone on Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House (Bookforum)

“Bearing in mind the epistolary origins of the novel as a literary invention, one can regard the results—sixty years of correspondence progressing to a narrative—as another Ellisonian magnum opus, one necessarily unfinished … is wisely divided by decade, starting with the nineteen-thirties, and Ellison’s voice is urgent from the start … The far more intimate letters to Murray cease in the sixties, presumably because they were now Harlem neighbors. Yet it can start to feel that such intimacy has become more elusive for Ellison, who has become less the Great Black Hope than the Great Explainer. And explanations, interesting though they might be, do not a novel make … The later letters portray a novelist busily not finishing his novel, despite working on it; along with his essays, gathered in two collections while he was alive, these letters contain his most extended, indispensable riffs. Earlier letters reacting to the Brown v. Board decision are remarkable, tying the hopes for his new novel with the hopes of a nation. But these later letters find a mind who could no longer attach his personal ambitions to the larger struggles of his day … Where the letters from the nineteen-forties are preparations for a strike and those from the fifties reverberate with his novelistic achievement, the later letters can start to feel like a way of avoiding the wider world, a world that this writer required in order to create. One feels, in these letters, an art that circles loss.”

–Kevin Young on The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison, Ed. by John F. Callahan and Mark C. Conner (The New Yorker)