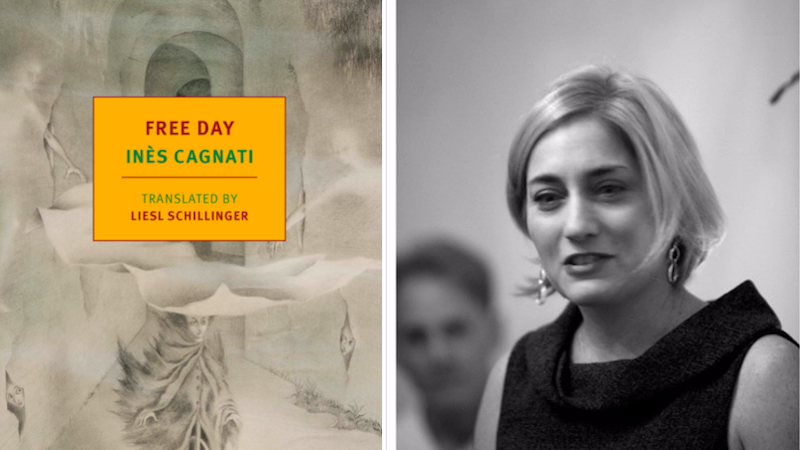

Free Day by Inès Cagnati, translated by Liesl Schillinger, is published today. Schillinger shares five books that give windows onto important political transformations.

The Time Regulation Institute by Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar, translated by Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe

This is an absolutely brilliant, sui generis satirical novel about the convulsions of ordinary life in Turkey in the aftermath of Atatürk’s westernizing reforms. It’s kind of Dickensian but wryer, more absurdist and less sentimental, I detect notes of Hašek. A brigade of natty busybody enforcers stroll Istanbul’s streets, asking passersby to show them their watches. Those whose watches do not show the correct time must pay a small fee. The hapless, lazy narrator, a habitué of Istanbul cafes, is drawn into a web of modernizing bureaucracy. The translation of this book must have been astonishingly difficult, because Tanpinar wrote in the enriched pre-Atatürk lexicon of Ottoman Turkish (Atatürk enforced a massive cull of the language), which included many words drawn from Persian and Arabic.

Jane Ciabattari: The idea that Atatürk built clock towers throughout Turkey to replace the calls to prayer or natural time with Western time and Western-style workdays is so telling. Tanpinar spent time in the political realm, as a member of parliament. Do you think that is what feeds the despair under the surface of his satire, as in passages like this? “I was fording a deep-sea cavern lined by the remains of knowledge and by all the ideas I had ever failed to grasp. As they swirled around my feet I moved forward, and with every step I felt the coil of unfounded beliefs, ungrounded frustrations, and unending despair tightening around my chest and arms.”

Liesl Schillinger: Oh, I wouldn’t call it despair—I think the attitude that underlies the novel is rueful, head-smacking incredulity, Catch-22-style. It’s important to know that this story unspins in retrospect. We know from the outset that the fictional “Time Regulation Institute” has collapsed—the bureaucrats completely failed to impose their clock-punching ethos on the vast cast of characters. The novel explains why through a rich, Ottoman meander of picaresque tales and shaggy dog stories that overwhelms (and laughs at) any Atatürkian will to order. I see this satire as a work of resistance: it suggests that no dictator, even a progressive one, can change the character of a people just by moving the minute hand on a watch face. That said, Tanpinar knows that a historical “minute” can last a very long time—a decade, a generation—and time lost can’t be regained. That accounts, in part, for the poignance of passages like the one you mention: the characters recognize “the crucial—and supportive—role error plays in human affairs,” and their own helplessness to stop perpetuating it.

By Night in Chile by Roberto Bolaño, translated by Chris Andrews

Bolaño’s best novel (or novella, it’s quite short), addresses the moral rot that seeped into Chilean society after Augusto Pinochet took power in a coup in 1973, tainting even its most prominent literary and spiritual sphere. It reads like a wise, lucid, enigmatic dream. At one point, Bolaño describes Chileans as moving like gazelles in a tiger’s dream: prey held in suspended animation in the mind of their natural enemy. In this book, a compromised, morally lazy Jesuit priest, Father Urrutia, agrees to instruct the Junta (including Pinochet himself) in Marx and Engels shortly after the coup. Read this book now to be stirred by the current unrest in Chile, where the people rose up in October to protest the injustices that have continued in Pinochet’s wake.

JC: Father Urrutia’s monologue sums up a life of moral decay and collusion—and also his experiences as a literary critic and poet, including an early encounter with Pablo Neruda. He describes parties hosted by María Canales, an aspirational novelist, and the basement rooms in her house where “subversives” are tortured. How does this vision of literary gatherings reflect the political transformation during Pinochet’s time?

LS: It’s difficult to safely reconstruct the history of a fabulist; Bolaño was born in Chile, but moved to Mexico City in his teens. And—here’s where it gets dicey—in 1973, after the coup, when Bolaño was 20, he moved back to Chile to fight for socialism. He was arrested, and, while he was in detention, overheard torture. There’s some debate over whether any of that really happened, whether he went back to Chile at all. But you’ll find an echo of this (apparent) experience at the María Canales parties Father Urrutia goes to: “The artists laughed, drank and danced, while outside on the wide empty avenues of Santiago, the curfew was in force.” Bolaño was profoundly anti-bourgeois; for him art and revolution were inextricable, and writers and poets who shift to accommodate dictatorship, who accept the status quo, bear personal guilt. That is what this story, in its “infrarreal” way, makes explicit—literally, as well as metaphorically.

The Storyteller by by Pierre Jarawan, translated by Sinéad Crowe and Rachel McNicholl

Which place defines you more? The home you know, where you’ve lived all your life; or a place you’ve never seen, which a charismatic relative persuades you is your only homeland? In this novel, a boy named Samir, born in Berlin in 1984, the year after his parents fled Beirut to escape the Lebanese Civil War, grows up obsessed with his cultural identity. His father abandoned the family when Samir was eight, presumably to return Lebanon. Why did he go? Where did he go? These questions torment him well into his twenties, heightening in intensity after the assassination of the Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, in 2005. The woman Samir loves, a Lebanese immigrant he met in their Berlin childhood, refuses to marry him until he resolves the mysteries that paralyze him. To move forward, he must go back.

JC: Samir’s quest for the truth of what happened to his father, after he left his family in Berlin—indeed, who his father was—is made especially suspenseful by the book’s structure, with each new character he visits adding a piece to the puzzle. Do you think this structure mirrors political changes that occur during a societal transformation?

LS: Absolutely. Yasmin—the woman Samir loves—is disturbed when she encounters a Homeland-style web of clippings and photographs spread across the walls of Samir’s apartment. He has been trying to piece together clues to his father’s existence to construct a clear and logical picture. This is what happens after every political upheaval; people seek to rebuild a recognizable narrative to inhabit, and to believe. We see this impulse now in the politically polarized United States of the Trump presidency. Different, sometimes conflicting, accounts emerge in Congress and in the news every day, and different groups of people rush to assemble these scraps into a cohesive truth that can explain what has happened and shore up their own identities. But it will take time for the pieces of the puzzle to come together, and for the full image to emerge.

Disoriental by Négar Djavadi, translated by Tina Kover

Like Pierre Jarawan’s novel, Négar Djavadi’s Disoriental enfolds a complicated personal and political history that news clippings, “articles stuffed with falsehoods,” can’t reliably explain. The narrator, Kim (Kimiâ), comes from a family of Iranian intellectuals (like the author’s) who emigrated from Teheran to Europe during the Iranian Revolution. In her thirties, in Paris in the 1990s, Kim wrestles with the fallout of her family’s political involvement, past and continuing; with her sexuality (she is lesbian, though not “totally indifferent to men”); and with her desire to have a child with her partner, Anna, through artificial insemination. She’s appalled to discover that French paternalist attitudes (and medical subsidies) present obstacles to the childbearing goals of unmarried women; the chauvinistic bureaucracy of the West is as hard to hurdle as the traditional mindset of her relatives. This rich and provocative book, steeped in story and event, translates attitudes to female autonomy and reproductive freedom that transcend borders of time, religion, class and continent.

JC: Kim waits in a fertility clinic in Paris among couples, thinking back to her grandmother, who was born in a harem, and her parents, who were targets of the Shah’s police before the mullahs of Iran’s current government. How do you think Djavadi is able to move with such fluidity from the personal to the global in this depiction of shifts in Iranian society?

LS: There’s no simpler thing to say, inadequate as this may sound, than that this book reflects momentous societal upheavals that Djavadi herself personally encountered, which doubtless have been stamped on her memory. This book is fiction, of course, but fiction is built on a scaffolding of actual events; and when that scaffolding is contained within the author’s own lived experience, it cannot help but strengthen the narrative. Djavadi was born in 1969, left Iran with her family soon after the Revolution, and was herself a witness, or at least a contemporary, of many of the signal events that shape the life of her protagonist, Kimiâ. She’s a wonderful storyteller, and rememberer; and judging from this book, likely has intricate, deep relationships with her extended family, infused with political engagement, a background she could draw on to inform her character.

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, translated by Clarence Brown

At this dystopian moment in world politics, everyone’s talking about 1984, but take a look at the novel that inspired it (or, at least, which George Orwell reviewed soon before he wrote 1984)—Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We. Orwell considered We conceptually and politically superior to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. In the oppressive totalitarian state Zamyatin conjures, there are not “thought police” but dream police—citizens’ subconscious and sex lives are tracked by invasive authoritarian enforcers. The dystopia Zamyatin painted has, alas, many echoes with today’s surveillance society—just think of China’s budding “social credit” program, which monitors citizens’ movements. Big Brother was a piker, compared to Xi Jinping. Zamyatin saw it coming.

JC: Zamyatin was writing only a few years after the Russian Revolution. His treatment by the new regime is reflected in lines like “One State Science cannot make a mistake” and passages that describe the “dance” of machinery as beautiful “because it is nonfree movement, because all the fundamental significance of the dance lies precisely in its aesthetic subjection, its ideal unfreedom.” He certainly predicted surveillance and torture techniques used in dystopian novels like 1984—and also in totalitarian regimes. Imagine a society in which beauty is destroyed because “to be original means to distinguish yourself from others. It follows that to be original is to violate the principle of equality,” a society that imposes brain surgery on those who rebel. How do you think Zamyatin’s own experience of post-revolutionary Soviet Union influenced his vision?

LS: Zamyatin had believed in Soviet Communism; he was an Old Bolshevik, a supporter of the 1917 October Revolution. But early on, as the Party swiftly extended its invasive control over citizens’ lives, public and private, Zamyatin turned against the regime. We, published in 1921, was an expression of his outraged disillusionment and a call to alarm. The first alarm it raised, though, was with the Kremlin; it was the first book banned by Soviet censors. Zamyatin was exiled to Paris. Later in the Soviet period, some writers managed to touch on hot-button subjects in their fictions without falling afoul of the Kremlin censors—notably the sci-fi and satire-writing brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (Lit Hub readers may have seen the Tarkovsky movie inspired by one of their novels, Stalker; I like their book Definitely Maybe). But the “principle of equality” you mention, commanded by the repressive world Zamyatin depicted, makes me think most of Kurt Vonnegut’s “Harrison Bergeron.” In that story, in a dystopian—and fairly imminent (2081)—American future, citizens whose gifts exceed the common run are required (by Constitutional amendments) to wear physical devices that suppress their natural advantages, so as not to demoralize ordinary people. Good-looking people must wear hideous masks; athletes and dancers are weighted down with bags of birdshot; and exceptionally intelligent people have to wear a “mental handicap radio” that emits piercing sounds to keep them from “taking unfair advantage of their brains.” Think about that, next time you see someone wearing AirPods…

*

· Previous entries in this series ·