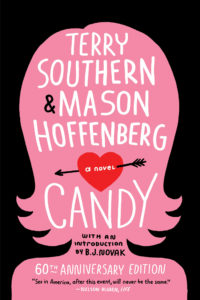

Boy, have we got some spicy-hot takes for you this week. Spiciest of all, perhaps, is Erik Wemple’s Washington Post review of humiliation magnet and beleaguered former White House press secretary Sean Spicer’s memoir, The Briefing, which calls the tome “a bumbling effort at gaslighting Americans into doubting what they have seen with their own eyes.” Over at the Los Angeles Review of Books, Khanya Khondlo Mtshali’s detailed critique of Morgan Jerkins’ debut collection of personal essays, This Will Be My Undoing, argues that the book “harks back to the days of the ‘first-person industrial complex,’ where publications would bait young women to cobble together their best traumas, only for them to be paid in exposure and virality.” Writing about Lawrence Osborne’s Only to Sleep: A Philip Marlowe Novel in the New York Times Book Review, acclaimed detective fiction author Laura Lippman finds herself “wide open to Osborne’s version of Marlowe, which forces us to wonder at times whether he’s still a man of honor.” There’s also Laura Miller on R O Kwon’s eerily powerful debut novel, The Incendiaries, and Dwight Garner on the 60th anniversary reissue of Candy—Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg’s outrageous sexual farce—which, he argues, “works in the era of #MeToo in part because it so coyly subverts the male gaze.”

*

“The best P.I. stories build slowly and keep the stakes relatively small. Osborne, who worked as a reporter along the border in the early 1990s, knows Mexico well and he passes that knowledge along to Marlowe … The game is afoot, with just the right amount of reversals and double-crosses. If certain moments seem illogical—well, that too is part of the Chandler oeuvre. The book’s greatest suspense centers on Osborne’s fealty to Chandler’s Marlowe, especially in the description set out in Chandler’s 1950 essay, ‘The Simple Art of Murder’ … As someone who has written P.I. fiction, I don’t always subscribe to Chandler’s dictates, particularly his assertion that ‘in everything that can be called art there is a quality of redemption.’ So I’m wide open to Osborne’s version of Marlowe, which forces us to wonder at times whether he’s still a man of honor.”

–Laura Lippman on Lawrence Osborne’s Only to Sleep: A Philip Marlowe Mystery (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“The themes in This Will Be My Undoing are the safe, harmless kind expected from so-called diverse writers whose biggest drawing card, according to the industry, is our ‘identity’ and ‘lived experience’ … Often, This Will Be My Undoing feels like a memoir for an older, more naïve internet age. It harks back to the days of the ‘first-person industrial complex,’ where publications would bait young women to cobble together their best traumas, only for them to be paid in exposure and virality. It’s also reminiscent of the time, which some may argue we still live in, when young black writers were encouraged to turn normal, everyday life events into after-school specials for white liberals desperate to be scolded for their racism, and do nothing about it … This is what is most frustrating with This Will Be My Undoing: Jerkins is so determined to present black womanhood as a state of pointed suffering that she ignores the myriad of reasons behind the statements she proposes as facts … This Will Be My Undoing falls into the tradition of art that upholds an easy and showy moralism. In an age where we want to be reminded of our good values through the art we consume, it is truly a book of its time.”

–Khanya Khondlo Mtshali on Morgan Jerkins’ This Will Be My Undoing (The Los Angeles Review of Books)

*

“Kwon evades the pitfalls of the religious novel by giving them the widest possible berth. Here are a handful of facts, she seems to say, if they even are facts. Make of them what you will … The Incendiaries is so parsimonious with description as to seem nearly starved of it. Kwon makes few attempts to summon an atmosphere or to flaunt arresting imagery, although when she does she acquits herself beautifully … The Incendiaries seeds such paradoxes in the mind of the reader. It doesn’t force them. It is full of absences and silence. Its eerie, sombre power is more a product of what it doesn’t explain than of what it does. It’s the rare depiction of belief that doesn’t kill the thing it aspires to by trying too hard. It makes a space, and then steps away to let the mystery in.”

–Laura Miller on R O Kwon’s The Incendiaries (The New Yorker)

*

“Even a half-witted political memoir would grapple with such a disconnect—perhaps by acknowledging some fault in the boss, or perhaps by comparing his low points with those of other presidents. Yet The Briefing isn’t a political memoir, nor is it a work of recent history, nor a tell-all, or tell-anything. Rather, it is a bumbling effort at gaslighting Americans into doubting what they have seen with their own eyes … Spicer marches in lockstep with the Trump administration’s now-common practice of maligning the news media. He rummages through the mistakes of major news outlets during the Trump era … On the larger question of Trump’s mendacity . . . uh, what mendacity? Twisting language into the incomprehensible—and meaningless—was a special talent of Spicer the press secretary and also clearly of Spicer the memoirist.”

–Erik Wemple on Sean Spicer’s The Briefing (The Washington Post)

*

“Every sentence in Candy seems to have a little propeller on it. Southern and Hoffenberg wrote the novel in tandem, mailing chapters back and forth, as a satire of Voltaire’s Candide and a parody of smutty novels. It was published in France by Maurice Girodias’s Olympia Press, which published quickie dirty books alongside higher-brow controversy-makers like Lolita, The Ginger Man and Naked Lunch. Candy became a best seller when it was published in America in 1964. William Styron, reviewing it in The New York Review of Books, called it a ‘droll little sugarplum of a tale’ … This episodic novel still lives because its joints are loose. It’s that rare book that smacks of a tight deadline only in good ways. There was no time to overthink it, to gum up the works … Candy works in the era of #MeToo in part because it so coyly subverts the male gaze. The men who leer after Candy are truly fatuous primates, fit for little but gibbering at the moon. Candy herself is no feminist paragon; no one escapes satirizing in this bracing commedia dell’arte. The authors wage guerrilla war on prudery; they view sex as yodelingly absurd yet rather fun and, in this fantasia at least, consequence-free. The authors send up untrammeled sexual longing in all its forms. Their ingrained hatred of authority and pomposity give the novel a rebel spirit.”

–Dwight Garner on Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg’s Candy (The New York Times)